6.5 Memory: Imperfect But Improvable

When analyzing something, scientists ask two types of questions: “How does it work?” and “How well does it work?” So far in this chapter on memory, you’ve read about how it works: Information enters memory through a series of stages (sensory, short-

Let’s now turn to questions about how well memory works. How accurate are our memories? What can you do to improve your memory?

Errors of Memory

Preview Question

Question

How do errors of memory show that human memory processes differ substantially from memory storage in an electronic device, such as a computer’s memory system?

How do errors of memory show that human memory processes differ substantially from memory storage in an electronic device, such as a computer’s memory system?

Memory is imperfect. People forget things: names, song lyrics, answers to exam questions. The imperfection in these cases is our failure to remember something seen or heard earlier.

This type of memory failure isn’t surprising. Many of the psychological processes you learned about in this chapter—

FALSE MEMORY. False memory occurs when people “remember” events that never happened in the first place. They recall a personal experience—

In a simple demonstration of false memory (Roediger & McDermott, 1995; see Chapter 1’s Try This!), participants first heard a list of words that were semantically related, for example:

|

sour |

honey |

|

candy |

soda |

|

sugar |

chocolate |

|

bitter |

heart |

|

good |

cake |

|

taste |

tart |

|

tooth |

pie |

|

nice |

|

Next, they saw a new set of words. Some of the new words were on the original list and others were not. Participants tried to remember which new words had been seen previously, on the original list.

You can envision how it felt to participate in this experiment through a simple exercise. Cover up the list of words above. Now try to answer the following questions:

Was “radio” on the list?

Was “pie” on the list?

Was “shoe” on the list?

Was “sweet” on the list?

240

If you’re like most of the participants in this study, you remembered that the list did not contain the words “radio” or “shoe” and that it did contain the word “pie.” And, like most participants, you probably remembered that the list contained the word “sweet.” But look back at the list now and try to find “sweet.” It’s not there! The researchers found that words like “sweet”—words similar in meaning to the original words but not actually presented—

This research finding shows that human memory processes differ substantially from memory storage in an electronic device, such as the hard drive of your computer. In electronic systems, memory is passive. The electronic device merely records information that is entered into it, places the information into a permanent storage system, and retrieves it when instructed to do so. The process is so simple that the computer couldn’t experience false memory. Human memory processes, however, involve active thinking. When you “input” information (in this case, read a list of words to be remembered), you do not merely store the information that is presented. You think about words and images that go beyond the information given. Being presented with words like “sugar,” “chocolate,” and “tooth” activates additional concepts in your semantic network, such as “sweet” (and perhaps also “dentist”). This capacity for active thought makes us more creative than computers. However, it also makes us prone to memory errors because, when we try to recall the information, a synonym or another word related to those on the list may come to mind.

People exhibit false memory not only for simple information, such as words on a list, but also for personal experiences. Elizabeth Loftus asked adult research participants whether they could remember details from four childhood events (Loftus, 1997). Three of the episodes she presented were real events that actually had happened in the participants’ lives. The fourth, however, was fictional; it was a story that involved the participant getting lost in a shopping mall at age 5. After presenting each episode, Loftus asked participants if they could recall experiencing the event.

If human memory were error-

241

Think about an event from your childhood you have described over and over to friends. How surprised would you be to learn that some of the memories you described were false?

How could human memory be prone to this error? Loftus explains that if someone suggests to you that an event happened (or merely that it might have happened), your imagination goes to work. You form a mental image of the event and imagine your thoughts and feelings in this situation. Even if the event never occurred, this “act of imagination … makes the event seem more familiar and that familiarity is mistakenly related to childhood memories rather than to the act of imagination” (Loftus, 1997, p. 74).

Loftus’s findings have substantial implications not only for psychology, but also for legal proceedings. As an example, in 1994 a 30-

Approaching my sixtieth birthday, I started to experience … memories, especially of my boyhood in London before World War II … [I remembered that] one night, a thousand-

[Later] I spoke of these bombing incidents to my brother Michael … five years my senior. My brother immediately confirmed the first bombing incident … but regarding the second bombing, he said, “You never saw it. You weren’t there. … We were both away at Braefield at the time. But David [our older brother] wrote us a letter about it. A very vivid, dramatic letter. You were enthralled by it.”

Clearly, I had not only been enthralled, but must have constructed the scene in my mind, from David’s words, and then appropriated it, and taken it for a memory of my own.

—Oliver Sacks (2013)

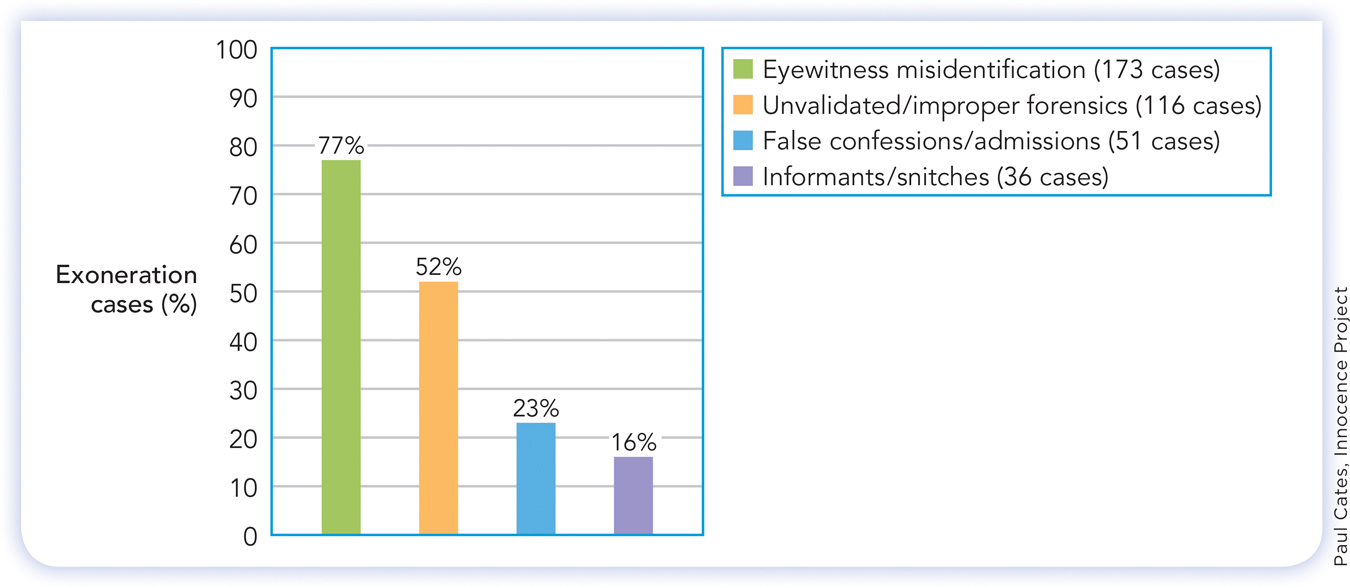

BIASES IN EYEWITNESS MEMORY. A second form of memory error also is relevant to legal proceedings. It is eyewitness memory, which is memory for events that we personally observe (as opposed to events we merely hear about). If you observe a car accident and report the details to police, or witness a crime and pick the perpetrator out of a line-

We often believe that eyewitness memories can’t be wrong. “I saw it with my own eyes!” people say to express this belief. But, in fact, these memories can be wrong. After witnessing an event, people may hear information that distorts their eyewitness memory (Figure 6.11). Research by Loftus shows how this can work.

242

In one study, Loftus showed participants a film with eight political demonstrators disrupting instruction in a classroom (Loftus, 1975). Afterward, participants were asked one of two questions: “Was the leader of the four demonstrators who entered the classroom a male?” or “Was the leader of the 12 demonstrators who entered the classroom a male?” Later, the participants were asked to recall how many demonstrators took part in the protest. The questions affected people’s eyewitness memory. Although everyone had seen 8 demonstrators, people who had been asked the question mentioning 12 demonstrators remembered that the number of demonstrators was approximately 9. Those who had been asked the question mentioning 4 demonstrators remembered that there were about 6 of them.

Is it unethical to use leading questions to influence someone’s recall of an event?

In related research, participants saw a film of a traffic accident and later were asked how fast the cars in the accident had been going (Loftus, 2003). In different experimental conditions, Loftus varied the phrasing of the question about the cars’ speed at impact. She asked some participants how fast the cars were going when they “hit” each other, and others how fast they were going when they “smashed into” each other. Again, the language used in the question altered people’s eyewitness memory (Loftus, 2003). Participants who heard the words “smashed into” as opposed to “hit” remembered the cars as going faster.

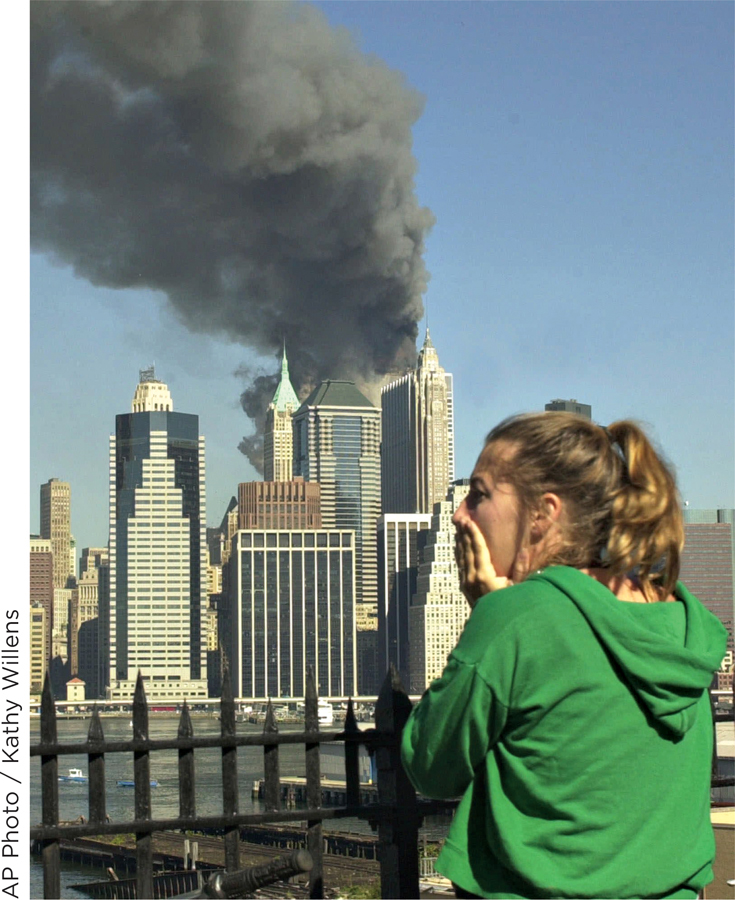

THE ACCURACY OF FLASHBULB MEMORY. A third type of memory error involves flashbulb memory, which is vivid memory of unexpected, highly emotional, and significant events. Every once in a while, as a society, we experience an unexpected and emotionally stimulating event: a political assassination, a terrorist attack, or a sudden natural disaster. When people first hear of the event, their emotions are aroused and senses heightened. When people look back on the event, they often feel they can see perfectly, in their mind, not only the event but also where they were when they first heard about it, almost as if a flashbulb had gone off originally and imprinted an indelible image onto their memory.

For what event—

243

Because they are so vivid, flashbulb memories seem like a form of memory that is not prone to error. You might expect that they are more accurate than ordinary memories of everyday events. But are they?

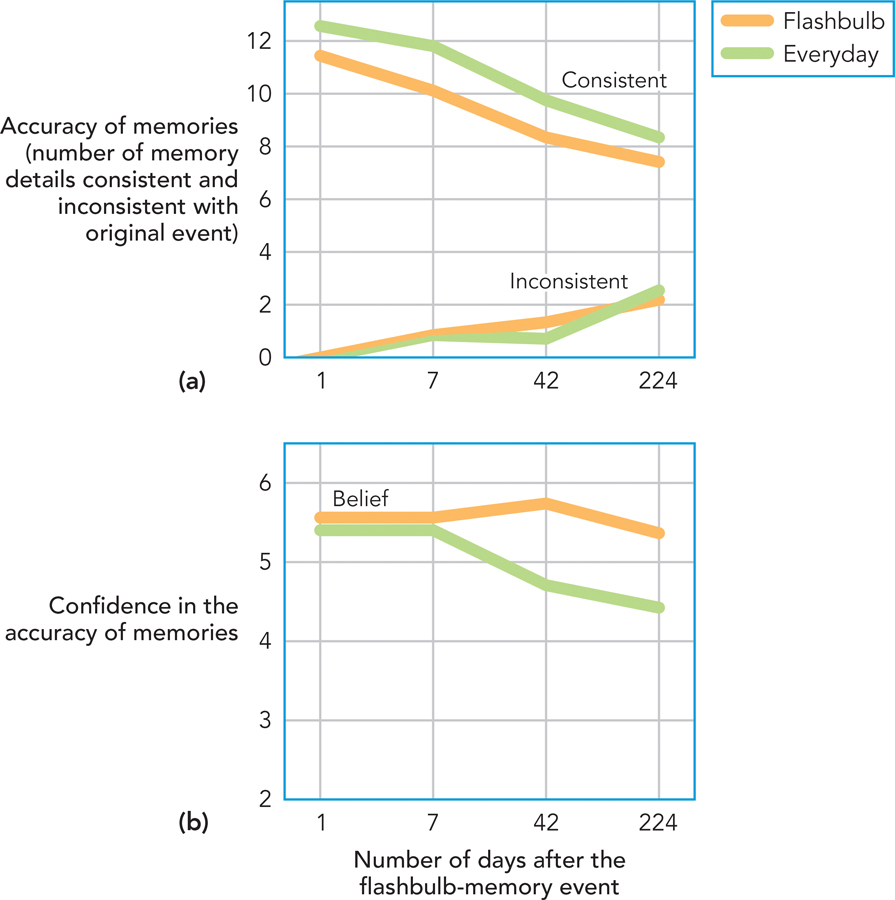

To find out, researchers began a study of memory immediately after a major “flashbulb” event: the 9/11 terrorist attacks. On September 12, 2001, they asked participants to report their experiences in detail—

The researchers then asked participants these same questions 7, 18, and 224 days later (Talarico & Rubin, 2003). This enabled them to study changes in both the accuracy of flashbulb and regular memories, and people’s confidence in that accuracy. Accuracy was measured in terms of the consistency between the original memory and the memory at a later time; if memory at a later time is not consistent with memory only one day after the event, then the later memory is inaccurate.

As you can see in Figure 6.12, over time people’s confidence in their everyday memories declined, but their confidence in their flashbulb memories remained high. Was their relatively high level of confidence in flashbulb memories matched by a high level of accuracy? No, people remembered “flashbulb” events with no greater accuracy than everyday events. Participants’ perception that their flashbulb memories were more accurate than their memory for everyday events was false.

244

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 11

lus8GWYPtwRdEPc7PKIg5Sxqm4yAR9YwqePDCXRyQv8jkrvNWjvYHeH8q+RPD6RnaUQ/jUsZNeXwsKaLH4TN5HdRlUMxmHrLTJDlJ4LWEQfbfLgAH1asup2i0vuE0bl1Z47eD+8vK1qJo/dPoQWr6WQX7y1LPWeuh4lsYnFtDgyXwGvjWq2PEDatdoQ5G7LO72UoxtPS+8619RUDXpg22hSd73eUBNjn5s8RUJF7SrA9Fp9eYwBGXt4m3Sr8xRDxa+BYzINIzphcD1YCJYijrOMsm6R6qVBGcYhXOrSAdMlb3eQvOgOBJ7Rn+qrqXEq7BYMoiiNcnqPnrfpNo78+e6NGZb1JrImm1bk8I2VFcZOJ9zPpYWY/aHkjfNfSyipubgl0CiJHnrx2y7zxxcqiubPahZXxAEwUzgj7lAwp4IbeWcFBugrAkDz4qnQ=CULTURAL OPPORTUNITIES

Autobiographical Memory

“I am smart.”

“I’m beautiful.”

“[I’m] a funny and hilarious person.”

—European American children’s self-

“I’m my mom and dad’s child, my grandma and grandpa’s grandson.”

“I practice the piano every day.”

“I play with my friend Yin-

—Chinese children’s self-

What do you notice about the above quotes? They suggest that European American and Chinese children view themselves differently. In Western cultures, self-

These different views of self may affect an aspect of memory: autobiographical memory, which is memory of experiences from one’s own life. As we experience life events, we construct memories of them; we retain mental images and factual knowledge of events and develop a storyline, or personal narrative, about our lives (McAdams, 2001; Nelson & Fivush, 2004).

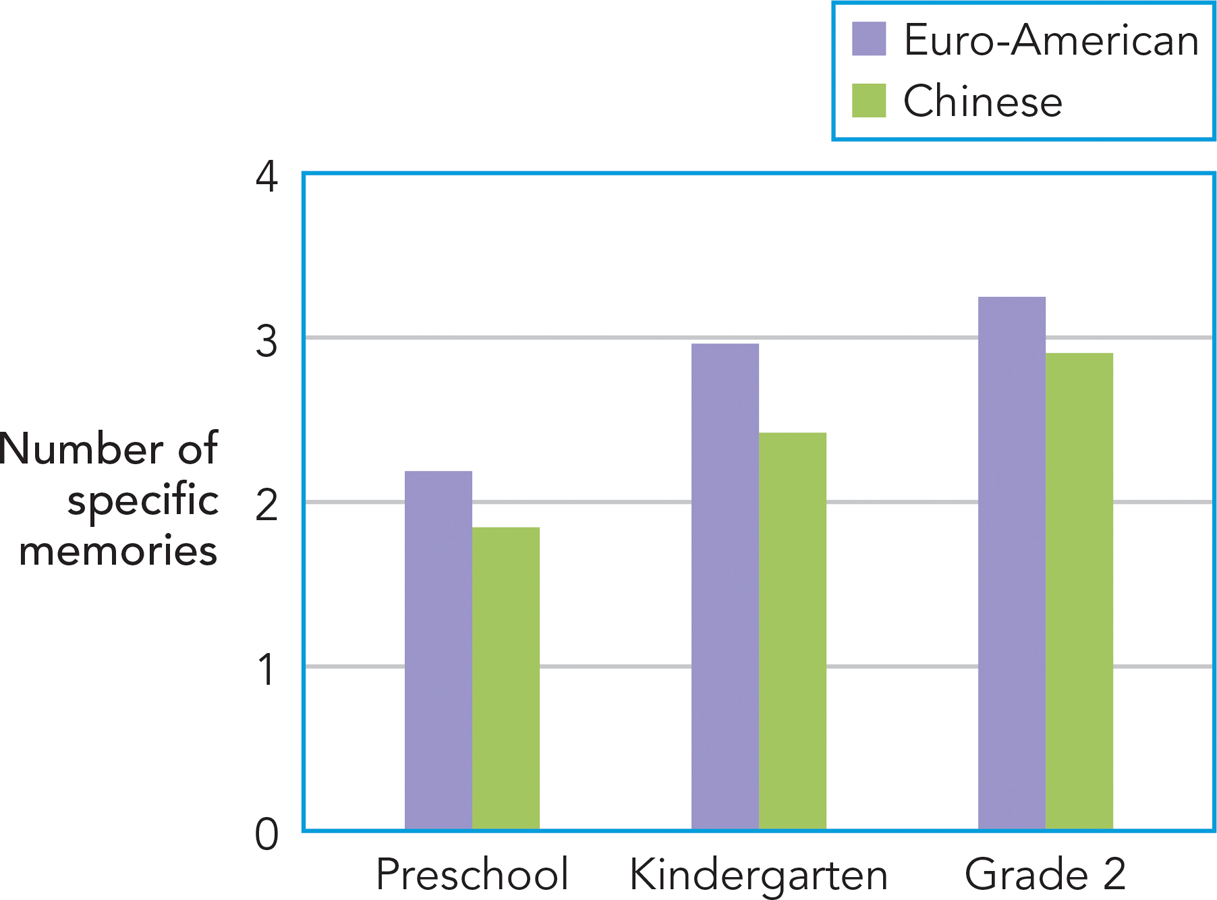

The psychologist Qi Wang (2006) explains how people from individualistic and collectivistic cultures might form different types of autobiographical memory. An individualistic culture draws attention to one’s own contributions to events and thus may cause people to dwell on their personal feelings during activities. As a result, people may have more detailed, rich autobiographical memory. A collectivistic perspective, by comparison, leads people to pay attention to the experiences of the group of which they are a part and the environment in which the group’s experience occurs. As a result, people with collectivistic self-

In a study with preschool children, kindergarteners, and second graders from the United States and China, children were asked to recall events from their lives (e.g., “how you spent your last birthday,” “a time when your mom or dad scolded you for something”). Their memories were coded to identify variations in specificity. A memory such as, “Once I said a bad word at home, then they got mad at me” would be more specific than a general recollection such as “My mom told me stories every night” (Wang, 2004). The autobiographical memories of children from the United States and China were found to differ (Figure 6.13). American children’s memories were more specific; they centered on “detailed, one-

245

The research findings should remind you of a broader lesson about psychology that you learned in Chapter 1: Different levels of analysis in psychological science inform one another. Wang was interested in the workings of the mind, specifically, the cognitive processes through which autobiographical memories are created. Yet her research was informed by research on persons and the cultural settings in which they live. Research on culture provided clues about the mental processes by which autobiographical memories develop.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 12

The following statement is incorrect. Explain why:

Improving Your Memory

Preview Questions

Question

What is chunking and how does it increase the amount of information a person can store in short-

What is chunking and how does it increase the amount of information a person can store in short-

Question

What are mnemonics and how do they improve memory?

What are mnemonics and how do they improve memory?

Much of this chapter has concerned memory’s limitations: Storage in sensory memory is brief; the capacity of short-

People have asked this question for thousands of years. In fact, the need to improve memory was greater in the past than today (Danziger, 2008). Before the invention of the printing press, copies of documents, even important ones such as sacred texts and legal proclamations, were scarce. People who needed to know the information in these documents had to memorize it. The demand for memory skills was so high that in ancient Rome, for example, training in memory was part of a formal education.

246

Today, technology does much of our memory work for us. We can access facts and figures on the Internet, so we don’t need to memorize them. Yet we often still do need that “old-

CHUNKING. As you’ll recall from earlier in this chapter, short-

Chunking is a strategy for increasing the amount of information you can retain in short-

A L J F K G W B B H O

If you’re like most people, you remembered a couple letters at the beginning (A, L) due to primacy effects and some at the end (H, O) due to recency effects, but you couldn’t remember half or more of the letters.

Now read the letters again, while trying to group together some letters. Here’s a hint: presidents of the United States. Let’s group them so that the virtue of the hint becomes obvious:

A L J F K G W B B H O

There are four chunks of information. Each one contains the initials of an American president: Abraham Lincoln, John F. Kennedy, George W. Bush, and Barack H. Obama. Each chunk packs two or three pieces of information into one memorable group. By remembering the four chunks, which is easy, you’re able to remember 11 individual letters, which was hard.

An even more effective example of the benefits of chunking involves the following list of numbers. Read it quickly and try to recall the numbers:

1 4 9 1 6 2 5 3 6 4 9 6 4 8 1

Again, you probably recalled just a few, from the beginning and end of the list—

Chunking doesn’t expand the storage capacity of short-

The second memory enhancement tool works on a different principle. It enhances memory by providing memorable methods of organizing the information you need to recall.

MNEMONICS. Memory can be enhanced by mnemonics, which are strategies for organizing information in memory. Mnemonic strategies usually add a small amount of information to material that you need to remember; the additional information increases the organization of information, making it easier to recall the material you need (Higbee, 1996). Just as a library cataloging system is useful for finding books in a library, mnemonics are useful for locating information in memory.

One simple type of mnemonic uses acronyms (abbreviations formed from the initial parts of other words). In a trigonometry class, you may have needed to remember that the sine of an angle equals the opposite side of a triangle divided by the hypotenuse, the cosine is the adjacent side divided by the hypotenuse, and the tangent is the opposite side divided by the adjacent side. How are you going to remember all that? You can use the acronym SOHCAHTOA (Sine Opposite Hypotenuse, etc.). The acronym is an extra piece of information to remember, but it’s useful: It organizes information that you otherwise might forget.

247

SOHCAHTOA only helps in trig classes, however. Other mnemonic strategies boost recall of diverse types of information (Higbee, 1996). For example:

In the peg system, information people need to recall is associated with other information that is easy to remember. The easy-

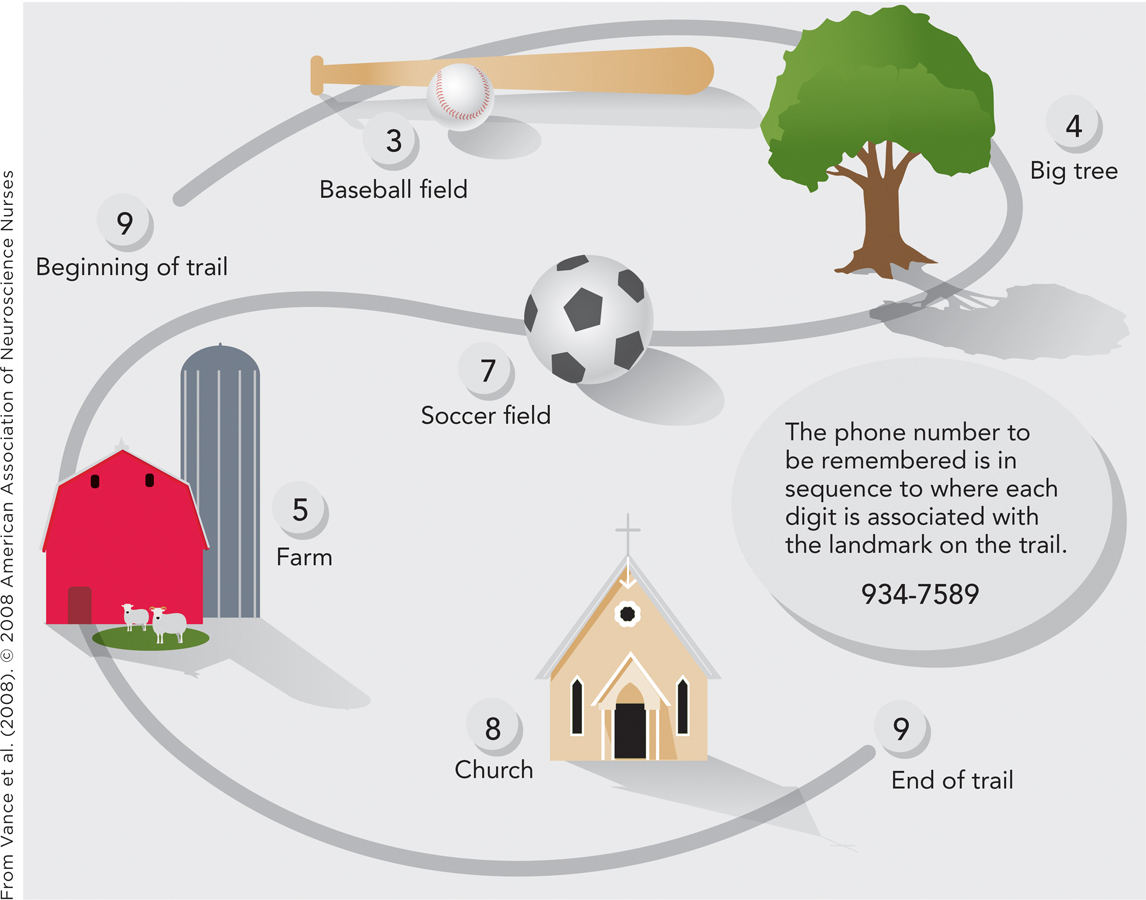

to- remember pieces of information are like pegs on which pieces of hard- to- remember information are “hung.” In one version of the system, the pegs are simple rhymes (One is a Bun, Two is a Shoe, Three is a Tree, Four is a Door, Five is a Hive). If you need to remember a set of grocery items— say, aspirin, milk, dog food, butter, ground beef— you “hang” them on the pegs. For example, you might imagine biting into a bun filled with aspirins, stepping into shoes filled with milk, seeing bags of dog food hanging from a tree with dogs jumping up to reach the food, and so forth. The weird- but- memorable images make the items easier to remember. In the method of loci, familiar locations are used to organize information in memory (Roediger, 1980). To recall items, one thinks of a familiar setting (e.g., your bedroom) and associates each item to be recalled with a specific location in that setting. Using our earlier grocery list, you might imagine placing aspirin on your bed where the pillow usually goes, putting a gallon of milk in front of your TV, and stuffing a drawer full of dog food. To remember the items, one “walks around the room,” inspecting the familiar locations to find each item (Figure 6.14). The method of loci can powerfully boost memory; “results are often striking and dramatic, [with people] using loci frequently recalling two to seven times as much as control subjects” (Bower, 1970, p. 499).

248