Chapter 7 Introduction

Learning 7

CHAPTER OUTLINE

Classical Conditioning

Classical Conditioning in Everyday Life

Pavlov and the Psychology of Classical Conditioning

Classical Conditioning Across the Animal Kingdom

Five Basic Classical Conditioning Processes

CULTURAL OPPORTUNITIES: Learning to Like Food

Beyond Pavlov in the Study of Classical Conditioning

Biological Bases of Classical Conditioning

Operant Conditioning

Operant Conditioning in Everyday Life

Comparing Classical Conditioning to Operant Conditioning

Thorndike’s Puzzle Box

Skinner and Operant Conditioning

Four Basic Operant Conditioning Processes

RESEARCH TOOLKIT: The Skinner Box

THIS JUST IN: Reinforcing Pain Behavior

Beyond Skinner in the Study of Operant Conditioning

Biological Bases of Operant Conditioning

Observational Learning

Psychological Processes in Observational Learning

Comparing Operant Conditioning and Observational Learning Predictions

Observing a Virtual Self

Biological Bases of Imitation

Looking Back and Looking Ahead

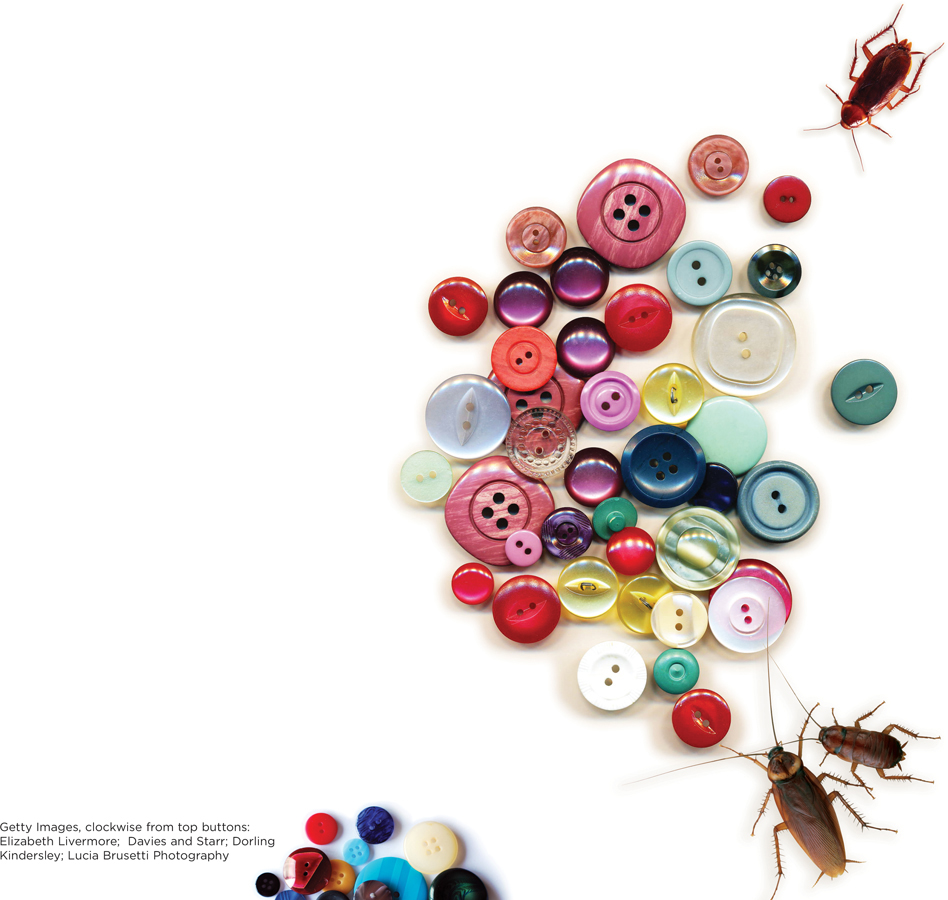

“IHAVE ALWAYS BEEN FEARFUL OF BUTTONS. For me, touching a button would be like touching a cockroach. It feels dirty, nasty, and wrong.”

Buttons???

“When I was younger,” the woman continued, “my brother used to tease me by opening my mum’s button tin. I hid in my bedroom until he put them away.”

“My cousin was wearing a button necklace one day. … I could not stand being in the same room as her” (Saavedra & Silverman, 2002).

The woman’s button fear sounds so bizarre that you might guess her case is unique. But it’s not. Consider this 9-

To learn more about this boy, psychologists conducted research in which they measured his reactions to buttons of different types. They found that he was moderately afraid of metal buttons, more afraid of large plastic buttons, and most afraid of plastic buttons that were small.

Why? Why would anybody be afraid of any buttons at all? An earlier event in the boy’s life provides a clue. At age 5, he had a startling, frightening experience that happened to involve buttons. While working on a school art project that used plastic buttons, he ran out of them. He went to his teacher’s desk for more, reached up to get some from a large bowl, slipped, knocked over the bowl, and a sea of buttons crashed down on his head. His natural fear of being hit on the head by falling objects somehow transferred to a fear of the objects themselves: buttons—

In one respect, the cases are unusual. Button fears are rare. But in another, they are commonplace: The psychological processes involved are pervasive, affecting many aspects of all people’s lives. You’ll find out about them in this chapter on learning. ![]()

VIRTUALLY EVERYONE YOU know can read and write, multiply and divide, make a phone call, and ride a bike. These abilities are so common that, if you didn’t know better, you might think they were innate—

Learning is any relatively long-

Learning teaches you not only how to perform behaviors, but also where, when, and how much to perform them. You learn not only how to play a musical instrument, but where and when to play it (at a time and place that doesn’t drive your neighbors batty). You learn not only how to tell entertaining jokes, but how much to do it (enough to be entertaining, but not annoying). Through learning, you adapt to outcomes in the environment: people’s attention, approval, disapproval, or boredom. Psychologists who study learning believe these adaptations to environmental rewards and punishments explain much of psychological life.

Psychologists have discovered different ways in which people learn. This chapter will present three of them: classical conditioning, operant conditioning, and observational learning. We will review the basic psychological principles involved in each, as well as the biological mechanisms that underlie the psychological capacity to learn.