7.3 Observational Learning

“When in Rome, do as the Romans do.” For the traveler, it’s valuable advice. For the student of learning, it’s something to ponder. What does happen in an unfamiliar environment where you don’t know the local customs—

Operant conditioning provides one answer. From this perspective, when entering an unfamiliar cultural setting, you’re like a rat on its first day in a Skinner box. The rat, at first, hasn’t the foggiest idea how to behave. Its initial actions are essentially random. It learns how to act only due to a slow process of trial-

Is this what it’s like for you when you enter a novel environment—

Most people learn to “do as the Romans” by watching the Romans. In unfamiliar settings, we often observe how others act, gain information about appropriate and inappropriate types of behavior from our observations, and then base our behavior on what we observed. This human ability to learn by observation enables us, quickly and easily, to fit in with the group rather than stick out from the crowd.

297

Psychological Processes in Observational Learning

Preview Questions

Question

How do the results of Bandura’s Bobo doll experiment contradict the expectations of operant conditioning analyses of learning?

How do the results of Bandura’s Bobo doll experiment contradict the expectations of operant conditioning analyses of learning?

Question

What psychological processes are involved in observational learning, that is, what processes are required for a person to learn to perform a behavior displayed by a psychological model?

What psychological processes are involved in observational learning, that is, what processes are required for a person to learn to perform a behavior displayed by a psychological model?

Curiously, this human capacity for learning by observation received little attention from psychologists studying operant conditioning. The psychologist Albert Bandura, however, paid it a lot of attention and pioneered research on observational learning. (Bandura used his findings about observational learning as a foundation for his theory of personality; see Chapter 13.)

In observational learning, people acquire new knowledge and skills merely by observing the behavior of other people (Bandura, 1965; 1986). Those other people are called psychological models, and observational learning thus is also referred to as modeling. In practice, the terms observational learning and modeling are used interchangeably.

LEARNING WITHOUT REINFORCEMENT. Observational learning is efficient. Through observational learning, people can acquire complex skills all at once, without tedious trial-

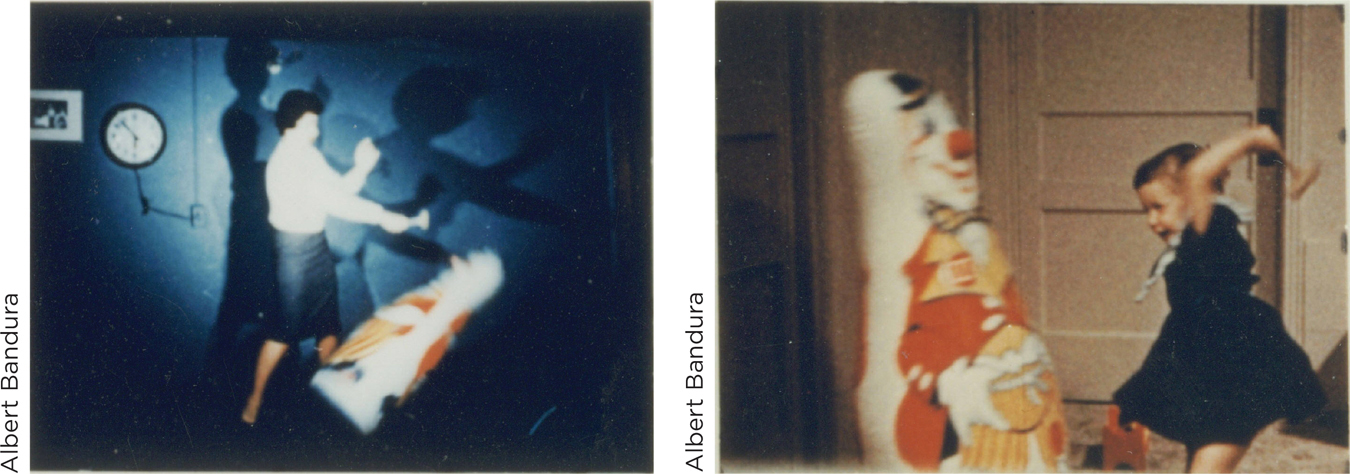

Bandura (1965) documented the power of observational learning in research (also discussed in Chapter 4). He showed children a short film in which an adult acted aggressively toward an inflated clown doll, or “Bobo doll.” The adult performed specific behaviors (such as hitting the doll in the nose with a hammer) that the children were unlikely to have performed before. Later, when the children were observed in a playroom, Bandura found that the children spontaneously performed many of the same behaviors they had seen in the film (see photos).

Note that the children performed these behaviors even though they never had been reinforced for performing them. There was no trial-

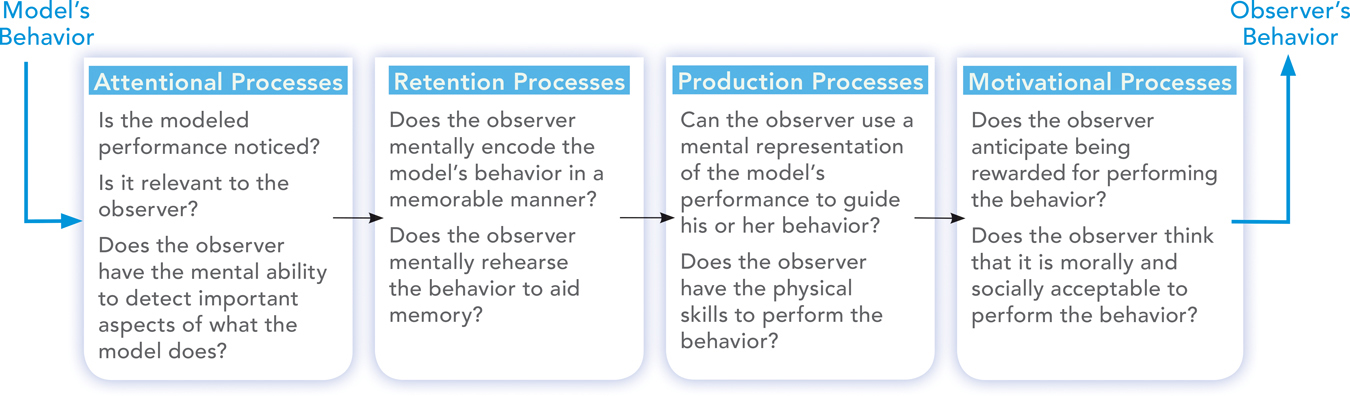

SUBPROCESSES IN OBSERVATIONAL LEARNING. Bandura recognized that his experiment had revealed a distinct form of learning that had been largely overlooked by operant conditioning researchers: To a much greater extent than the rats and pigeons in a Skinner lab, humans have the ability to learn complex acts through observation. To explain this ability, Bandura (1986) analyzed subprocesses in observational learning—

298

Attention: The observer must pay close attention to the model’s behavior.

Retention: The observer must create, and retain, memory for the model’s actions.

Production: The observer must be able to draw on a mental representation of the model’s behavior and must have the basic motor skills necessary to produce the remembered action.

Motivation: The observer must be motivated to perform the behavior. Even if the observer has learned the action, he or she still might decide not to perform it.

CONNECTING TO PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT AND THE BRAIN

The fourth step in Bandura’s analysis, motivational processes, underscores a point that received relatively little attention from Skinner. It is the distinction between acquisition and performance. To perform a behavior is to engage in that behavior. To acquire a behavior is to have the potential to engage in a behavior. As Bandura emphasized, people can acquire the skill to perform a behavior, yet not be motivated to do it. By watching a crime show on TV, you might learn ways to commit a criminal act. Nonetheless, you likely choose (wisely) not to perform those behaviors. Learning, then, cannot be measured solely by studying what individuals do because they may have learned actions that they choose not to perform.

In summary, research on observational learning substantially expanded psychology’s understanding of learning in two main ways. First, it highlighted a phenomenon that had received little attention from previous learning theorists (i.e., Pavlov, Thorndike, Skinner): people’s ability to learn behaviors rapidly through observation alone. Second, it explained that phenomenon through a novel set of conceptual tools. Rather than referring merely to simple stimulus–

299

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 17

Kit2mguseeug4TChaN7u8xpjAkTnFkulqfpp1eyvunVqBprSK7u7OCcBrDjRLOV8mGrIfYvlqXYSnhlcsd8o+Of9HrZ3BJh8dBVbNAyOgnOtsjGpym61nhiteooBeJvUMNtOljAe0VQ=Question 18

VsNf/xwWYzuouOtWDhxKb9mkOLEh1Ic2xtwTy8eIo5KCcX6dt7kHbbN3+Mhnv2hIMy4WlVkzIL929Qz2rqYlzTComU19WroNJ/PE+4NlSOKIAx/ZzOhXgUyncLT31XxBD3y5ZPl602gsLs4IF0MAgHn1N5+nvy/1MRrr1Y0QZ2ZexvmQrKc3Z1sc6aQoW2nEA1BKDTFkiH1N23kWSip8nYQ3kQ0k/bn2w46twlks5fHGAVVOYMP0rBqdORCAj4OsXkI/BHhxa09l1JcIualaaTBZWjGmACrVj/x8x/iMttTVw6F2mP9MjevZRqp3Y4Y9DnXLGBWz4I5z+B8wF02xKOsLwmQPdVC5i3o385Ot5sY1x4xmmYSMzQaVhcAVXsQwBtbTMe2W7eA=Comparing Operant Conditioning and Observational Learning Predictions

Preview Questions

Question

Can spanking increase aggression in children?

Can spanking increase aggression in children?

Question

Does research on the effects of spanking support theoretical predictions made by operant conditioning or observational learning analyses?

Does research on the effects of spanking support theoretical predictions made by operant conditioning or observational learning analyses?

Sometimes models send contradictory messages. They model one type of behavior, but tell others that this behavior is not allowed. An example of this is spanking by parents who are trying to control their children’s unruly, aggressive behavior. The spanking is intended as a punishment. An operant conditioning analysis would thus suggest that the spanking would make children less unruly. Yet the parent who is spanking is providing a role model of aggressive behavior; the spanking itself is an act of physical aggression toward the child.

What is the effect of spanking? To find out, researchers conducted a large-

The results suggest that spanking increases children’s aggressiveness (Taylor et al., 2010). Mothers who spanked their children more frequently at age 3 produced children who, at age 5, were more aggressive. This surely wasn’t their goal; mothers who spanked were trying to establish a strict household that produced children who were well behaved. But their efforts backfired. Note that spanking predicted age 5 aggressiveness even after the effects of age 3 aggressiveness were accounted for statistically. The results, then, could not be explained in terms of the child’s personality trait of aggressiveness alone. Instead, they strongly suggest that parental behavior affected the child. Psychological modeling (children saw their parents acting aggressively) was more powerful, in this case, than operant conditioning via response consequences (being spanked for unruly behavior)—just as Bandura would have predicted.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 19

zymhiGsnm3KJuaWB3con+XI7hL8d7WLk/RlzidDJyigEwTzTPYp8QO04pkw8xSl4NQrZHKDO9Vru56EGMBTwFfOCuLkmnoYMgm3KKR3Jvxy+A/7STgvWwn4V4yM7x5utbz2QCyY/PPY6xbefnyGSq94kS2nSMhRFlhprO5Qb1jZZPlfpJgiPYfb5zzQkQIshH3Ozvjl7ALrHGI4LNQNAwo4Q8RhQjGmwVsY3l/HShLqAXzK7BSsgvYb0UiSR1eiiJJ9l9HYkvyfmM30h2fSEZ9ehVFCwquHGTCVnaBkWEknrvyf8n0PQ2dGW6Xg=Question 20

rayGKbUB7vYcMz75H2Qk68larw7/p3twp6oSsXCZGRjrEkLLOyWyg+sN9Hn5yxDxE+wfv16yzmy6lajfgB6RfzboGkc4/6+4Jw0EPtk/+83K0VV4l8ycYwkoW7tGRy9tJB00isM+1A7Pi06x8Hye9g==300

Observing a Virtual Self

Preview Question

Question

What is one way in which modern computer technology can enhance the power of modeling?

What is one way in which modern computer technology can enhance the power of modeling?

People are exposed to a wider range of psychological models in contemporary society than they were in the past. Centuries ago, people in rural villages learned social behaviors and professional skills by observing others who lived in their town (Braudel, 1992). By the mid-

Thanks to contemporary digital technology, researchers can overcome a problem that, in the past, limited the effects of psychological models—

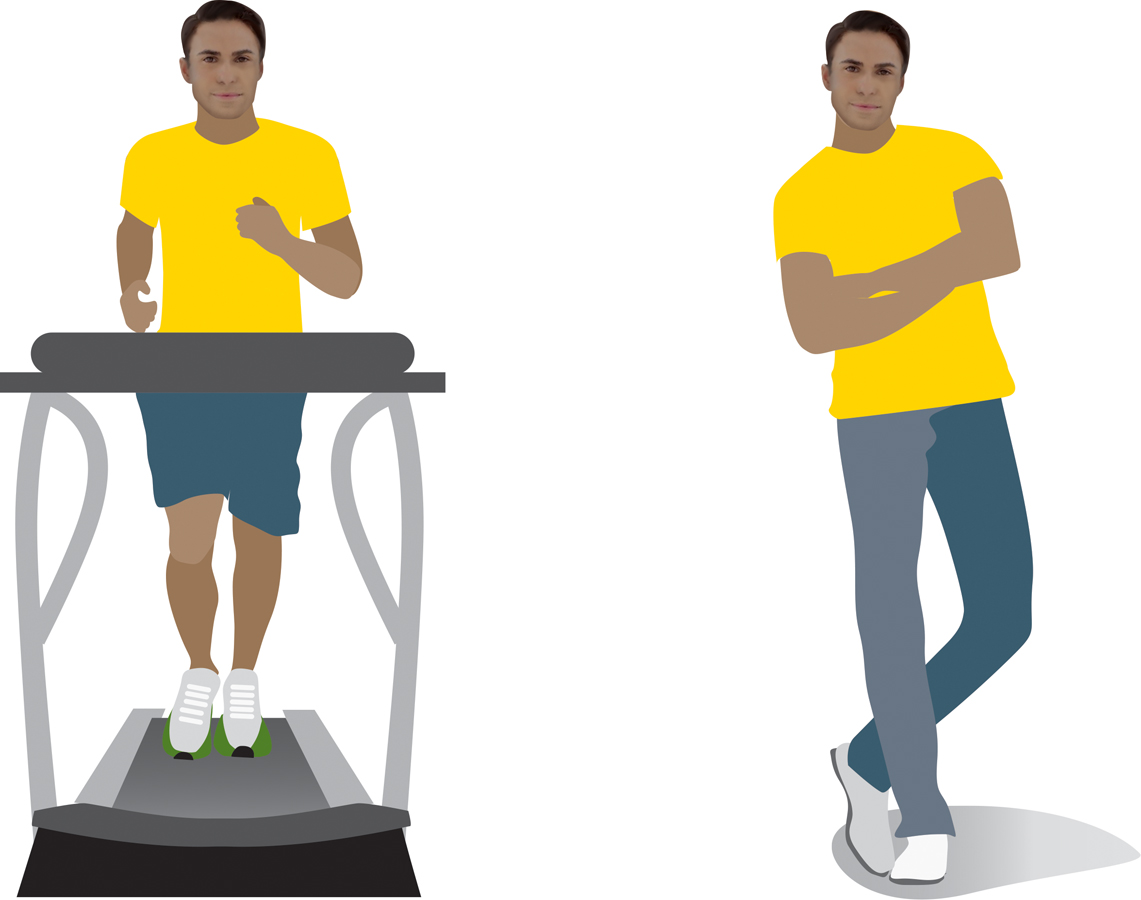

One way to do this is through virtual representations of the self (VRSs; Fox & Bailenson, 2009). A VRS is a modeling display in which people observe an image that looks just like them. Here’s how it’s done. If you participate in a VRS study, psychologists first take a digital photo of you. They then enter the image into computer software that creates a three-

In one study (Fox & Bailenson, 2009), VRSs were used to help people to improve their health by getting more exercise. Participants were assigned to one of three modeling conditions. In one, they watched a computer-

What would it be like to watch a virtual version of yourself exercising?

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 21

One way to be your own best model would be to participate in a VRS (K2oqol8KM585XPSN ncsruc6RJ2Zq8NKLB08NvlmxsNk=of the Vb39nosIY/nnLDWo) study because watching a VRS can be highly motivating.

301

Biological Bases of Imitation

Preview Question

Question

What neural system directly contributes to organisms’ tendency to imitate the behavior of others?

What neural system directly contributes to organisms’ tendency to imitate the behavior of others?

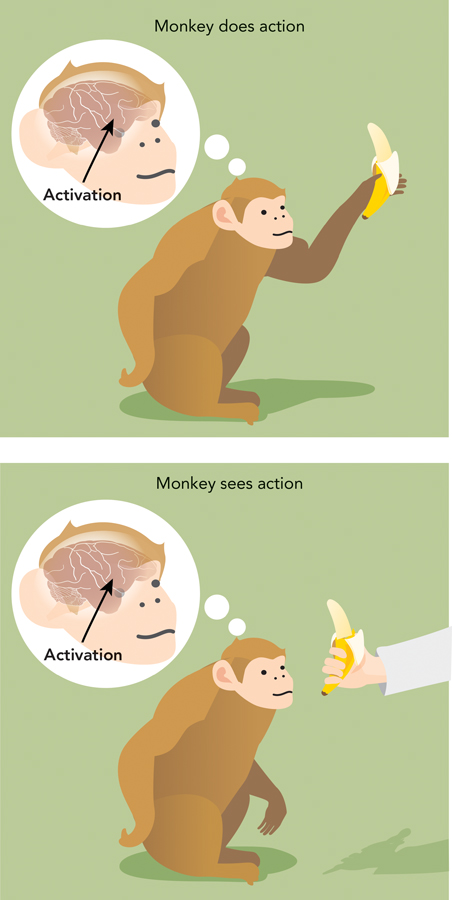

People’s ability to learn by observing others’ behavior can be explained not only at a psychological level of analysis, but also at a biological level. Our brains contain mirror neurons, which are cells in the brain that fire when an organism takes action and also when it observes another organism take that action (Rizzolatti, Fogassi, & Gallese, 2001). Their firing contributes to the imitation of the other organism’s behavior.

Mirror neurons are located in the brain’s motor cortex, which contains neural systems that control the movement of the body (see Chapter 3). Whenever you make a movement—

Mirror neurons originally were discovered in research with monkeys (Rizzolatti et al., 2001). Experimenters recorded neural activity in monkeys’ brains during two activities: (1) when they themselves picked up a piece of food, and (2) when they observed someone else (either a human or another monkey) pick up a piece of food. The activities—

Importantly, these mirror neurons did not fire when the monkeys merely observed a piece of food, or observed a hand making a grasping movement when there was no food in sight, or when they observed a piece of food being picked up with pliers instead of by hand. The mirror neurons were highly selective. They fired only when the monkey observed the action of a hand picking up the food. This shows that mirror neurons are highly specialized. Each mirror neuron is designed to mirror a particular motor movement (in this case, the picking up of an object with one’s hand).

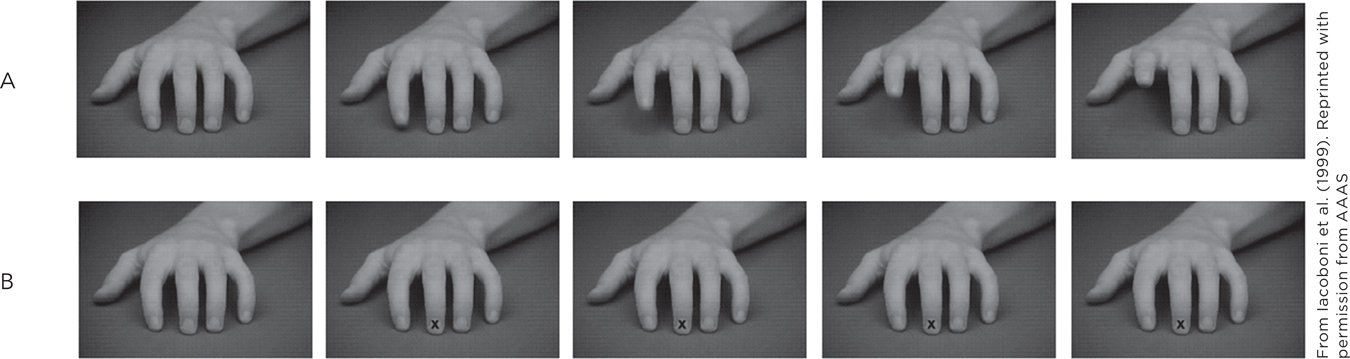

Further research revealed mirror neurons at work in humans (Iacoboni et al., 2009). Researchers observed people’s brain activity while they performed a simple task: lifting their index finger. They told participants exactly when to lift their finger by showing either of two displays on a video screen: (1) a hand in motion, lifting one of its fingers, or (2) a symbol (a letter X) that appeared on a static picture of a hand (Figure 7.19).

Although the task that participants performed in the two conditions was the same (raising a finger), brain activity in the two conditions differed. Brain activity was higher when participants moved their finger while observing a moving hand than when they looked at a static picture of a hand (Iacoboni et al., 2009). Observing a motor movement by someone else (the hand lifting one of its fingers) automatically activated the participants’ mirror neuron system. This result thus showed that there is a system in the brain, the mirror neuron system, specifically dedicated to copying observed actions.

302

THINK ABOUT IT

Does mirror neuron research explain, at a brain level of analysis, earlier research findings on observational learning? Or does it only explain some cases of observational learning? Recall that Bandura’s analysis of observation learning included complex mental processes (storing, and drawing upon, mental representations of behavior observed in the past) that seem to go beyond the phenomena addressed in mirror neuron research.

Mirror neurons may explain a variety of common, and sometimes puzzling, behaviors in animals and people. Why do birds instantly fly away when observing one bird taking flight? Why do people yawn when they observe someone else yawn? In these and innumerable other cases, observing an action may automatically activate neurons that mirror the action being observed.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 22

When you observe someone else perform a motor movement, the uPlw4J7VMhQcp595 neurons in your brain automatically prepare your body to make that same movement.