8.1 Categorization

If your psychology instructor held in her hand a thin rectangular metal object with a video screen and it suddenly started to ring, you wouldn’t think, “Hey, look at that, a ringing piece of metal with a video screen.” You’d think it’s her “smartphone.” If she was carrying 500 sheets of paper bound together with some cardboard on the top, bottom, and one side, you wouldn’t think, “Look at all that paper and cardboard.” You’d think it’s “a book.” If she was accompanied by a short-

All this might sound kind of obvious. Yet these simple examples illustrate a critical fact about thinking: People categorize objects and events. To categorize something is to see it as a type of thing, that is, as a member of a group. Almost every time you see anything—

309

Let’s explore two ways in which categories differ: (1) category level and (2) category structure.

Category Levels

Preview Question

Question

What categories are most natural to use?

What categories are most natural to use?

Consider three categories we just mentioned: (1) mammal, (2) dog, and (3) mixed-

Category level thus refers to a relation between categories in which low-

What did you have for dinner last night? How would you describe it if you used too high-

The psychologist Eleanor Rosch (1978) explained that some category levels seem more natural to us than others. Some, in other words, come to mind spontaneously, whereas others are rarely used. Suppose a friend purchases a new item—

Middle-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 1

vIbWM6288ycOASJb8vAcEVsQMMS8/2xXSUJoiahtzXHFipFInjIi0xoNurppqkAwp2pHrwHbBBLsiPXbfbE3NwSzj4lLFGDtGHwLlKJwj7sa/aduP0QueBlAqgNlGrvMk77ryRKNS95pZvJng1B3NcA5/xqOcd9URIBFkrRvKeFyY58prdhd51Dq07b0Y/l1WoOrVkCrEIIoKm1J0UZLQrtjshGkiSaU+QSBO6m4Rq+g1bkHbYkOJQtV1ugrX5GZIx1Jb6hAKepKvRE+n9FOUw==Question 2

5+K2zdQR8oQ/CAjlx/Gmd5UZFN6OHVktMY92zG9rN+6I86LWn9LVaY3mez2ry1XQtdIRNg==310

Category Structure

Preview Question

Question

What is the structure of categories?

What is the structure of categories?

Categorization is not to be taken lightly. There is nothing more basic than categorization to our thought, perception, action, and speech. Every time we see something as a kind of thing … whenever we intentionally perform any kind of action … and any time we either produce or understand any utterance of any reasonable length, we are employing … categories. Without the ability to categorize, we could not function at all.

—George Lakoff (1987, pp. 5–

How do we know if an item fits into a category? Category structure refers to the rules that determine category membership. Different categories have different structures, that is, different types of rules. You can see this with a simple exercise. Perform these two tasks:

Task #1: Categorize the following numbers into the categories “odd” or “even”:

17

44

100

53

9

Task #2: Categorize the following into the categories “educational” or “entertaining”:

a calculus lecture

The Simpsons

a documentary movie

a trip to an art museum

a Rachael Ray cooking show

The instructions were the same, yet the tasks differed. In #1, categorizations were clear-

The categories “odd” and “educational” (or “even” and “entertaining”) have different types of structure. “Odd” has a clear-

CLASSICAL CATEGORIES. Classical categories have rules that determine membership unambiguously. There are no “in-

“Odd” and “even” are classical categories. The defining feature for “even,” for example, is “a whole number that, when divided by 2, results in a whole number.” If a number has that feature, it is even; if not, it is not. Another example is “bachelor.” If you are a man and not married, you are a bachelor; otherwise, you’re not. There are no in-

FUZZY CATEGORIES. The boundaries of many everyday categories are “fuzzy” rather than clear-

You’ve already seen a fuzzy category: “educational.” Was the Rachael Ray show educational? Maybe no (it’s not as educational as calculus), but maybe yes (you do learn something). Another example is the category “athletes.” Soccer players are athletes. But what about race car drivers? Pool players?

311

A philosopher, Ludwig Wittgenstein (1953), first explained how categories violate the classical structure. When looking closely at how people actually use categories, he explained, you rarely see explicit rules and sharp boundaries like those that define even/odd or bachelor. Instead, rules are subtle, ambiguous, and used flexibly. He gave the example of the category “game.” What defines the category? It’s hard to say. Checkers and Monopoly are games—

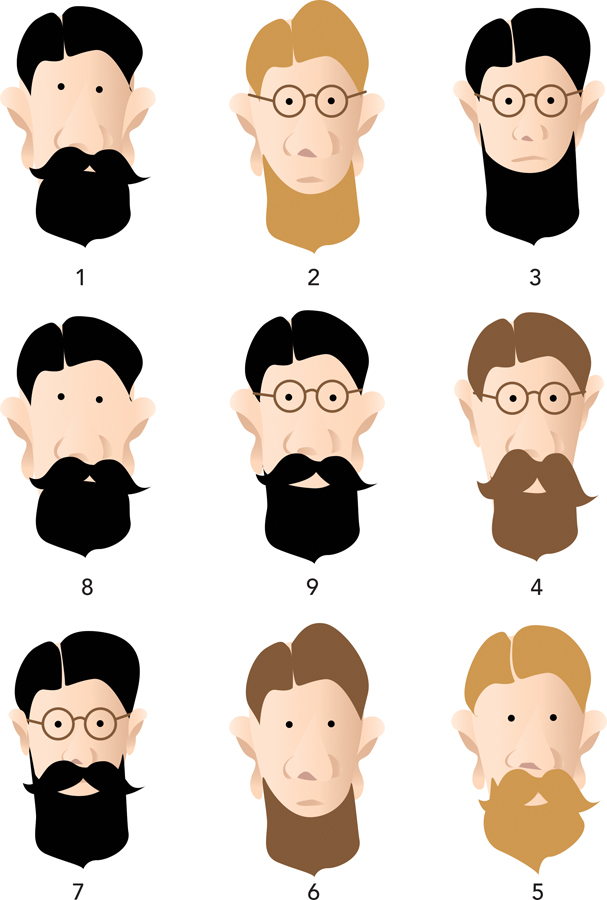

Wittgenstein suggested that categories have a family resemblance structure: Category members share many features, but no single feature is absolutely necessary for membership in the category. Category members are like members of a family (Figure 8.1); they are similar without necessarily sharing any one feature. The category “game” is like this. There is no one thing an activity must have to be a member of the category—

Eleanor Rosch proposed a related idea: prototype structure. In a prototype structure, a category is defined by its most typical, central member. That member is the prototype, the “clearest case of category membership” (Rosch, 1978, p. 36). Individual items are closer or farther from the category’s center, depending on their resemblance to the prototype.

Have you ever tried to define what art is? Do you think this a category for which the concept of family resemblance is useful?

A category with prototype structure is “chair.” A wooden chair, of the sort you might find at a kitchen table, is a prototypical chair; it’s at the center of the category. A large vinyl bag filled with small pieces of foam also is a member of the category “chair”—it’s a “bean bag” chair—

What does the prototypical dog look like?

312

When you think about categories, your thoughts reflect the prototypicality of its members (Rosch, 1978). Think of a bird. Now think of another. And another. If you’re like most people, the first one that came to mind was a prototypical bird (e.g., a robin). If you thought of one low in prototypicality (penguin, ostrich), it probably wasn’t until the second or third bird. When listing examples of a category, people tend to mention prototypical members first.

Prototypicality also influences the speed of thinking. When judging whether items belong to a category, people make judgments about prototypical items more quickly. Consider the category “sex.” People more quickly judge that prototypical items (lust, arousal) are category members than less prototypical items (candles, bed). Response speed also reveals individual differences; people with a stronger heterosexual orientation more quickly judge that “reproduction” is a member of the category (Schwarz, Hassebrauck, & Dörfler, 2010).

Prototypes also affect emotions. People like prototypical members more. This is true even for abstract categories. When participants viewed random patterns of dots, they liked the patterns that were similar to the most typical, average dot pattern—

Prototypes can vary across cultures. Consider, for example, the category “good person.” To find out if its prototype structure varies, researchers asked people from a variety of countries to list the qualities they associate with a “good person” (Smith, Smith, & Christopher, 2007). Ethical and moral qualities such as honesty, kindness, and caring for others were part of the prototype universally. Yet there were also cultural differences. For example, in Taiwan but not in the United States, being self-

AD HOC CATEGORIES. Not all categories have classical or fuzzy structures. Ad hoc categories are groupings of items that go together because they relate to a goal that people have in a specific situation (Barsalou, 2010). The phrase ad hoc means “for this”; ad hoc categories thus contain items that are all useful for some common purpose.

The following example (from Little, Lewandowsky, & Heit, 2006) shows why ad hoc categories need to be included among the types of category structures. Consider these items:

Pictures

Cats

Children

Jewelry

Money

Documents

313

Do these items strike you as members of any one category? They would if a house caught fire. They are members of the category “things to save from a burning house.” This ad hoc category has a meaningful structure, but it isn’t classical or fuzzy; there are no clear-

You may have noticed that the categories we have discussed—

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 3

ViXAXb0e+G2oG3fBSMxboUeungYsFZlPh5UxTf3C+/H7iT8x3UepaR3u5j0T+N7e82Kt55+YockbhBgzJz+aWx9Y4k1zCMrpupKE7J0Xz502W7XV7hltbCF4q5wpjWNQah4YaykJFw3EYrbq8hKXhuecDR8VtacgXVeikrgH6jVy6IF1kVmzANYUak1gY+ziwwMXTHu5eP782jwOQqxgxg==Question 4

NjI0kBPMMk0NgZO/wZr9MREfyq3kq0BIjAU0ZqV0aB1FyTt2eSUPSwyTG5zeyg+N1Yq8UARAObb+8icz4G1N99hC7f9jHFHt3d0TKeuIB0U=

THINK ABOUT IT

Most categories involve words. So which do you think came first: the category or the word? Do you first formulate an idea and then learn a word for it, or do you first learn a word and then its meaning (the category of things to which it refers)? (We’ll talk about this later in the chapter, in the section on language and thought.)