8.6 Mental Imagery

Picture yourself in a building you know well, such as the house where you grew up. How many windows were on the front of the building?

Now consider this question: How did you figure out how many windows there were?

If you’re like most people, you formed a picture of the building in your mind and counted the windows. If so, you relied on a distinct form of thinking called mental imagery. Mental imagery is thinking that involves pictures and spatial relationships (i.e., relationships involving location in space) rather than words, numbers, and logical rules. When thinking with mental imagery, you have the experience that you’re “looking at a picture” in your mind. Let’s consider two types of thinking that illustrate the power of mental imagery: (1) mental rotation and (2) contemplation of mental distance.

340

Mental Rotation

Preview Question

Question

What determines how quickly we can rotate images in our head?

What determines how quickly we can rotate images in our head?

Much insight into mental imagery has come from research by Roger Shepard and colleagues on mental rotation. Mental rotation is the ability to turn an image in your mind, much as you would turn a physical object in the world.

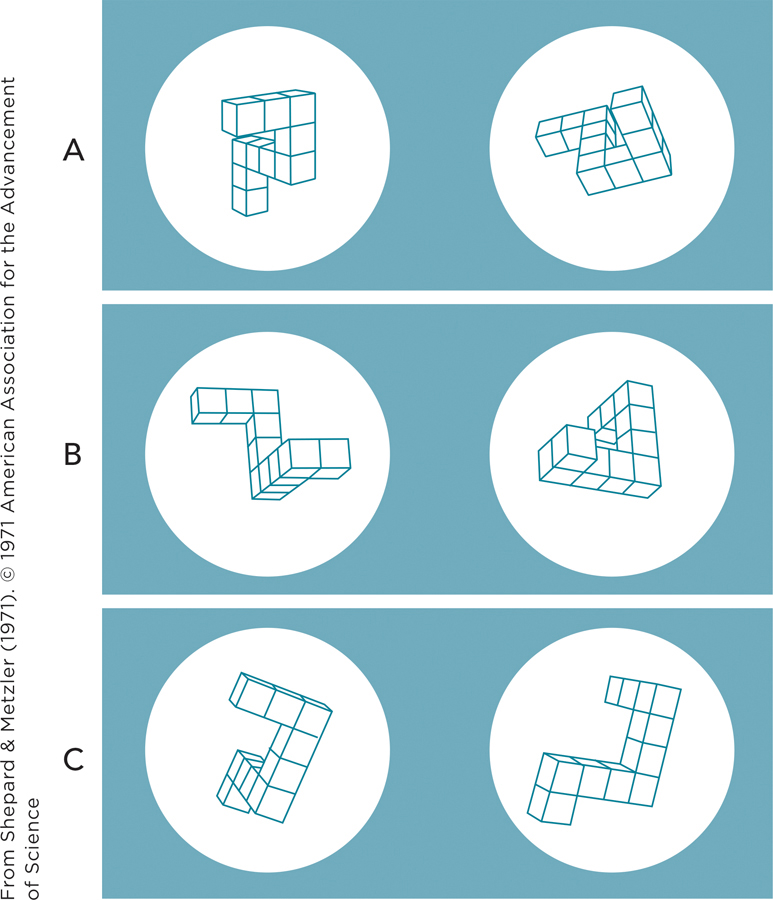

In their research, Shepard and colleagues showed people pairs of abstract objects (Shepard & Metzler, 1971). Participants had to determine whether the objects were the same (i.e., had the same shape) if rotated. As shown in Figure 8.9, some pairs were the same; they could be matched up through rotation. Others did not match no matter how they were rotated. The study’s dependent measure was the time it took participants to rotate the objects mentally, in other words, to determine whether the objects matched after rotation.

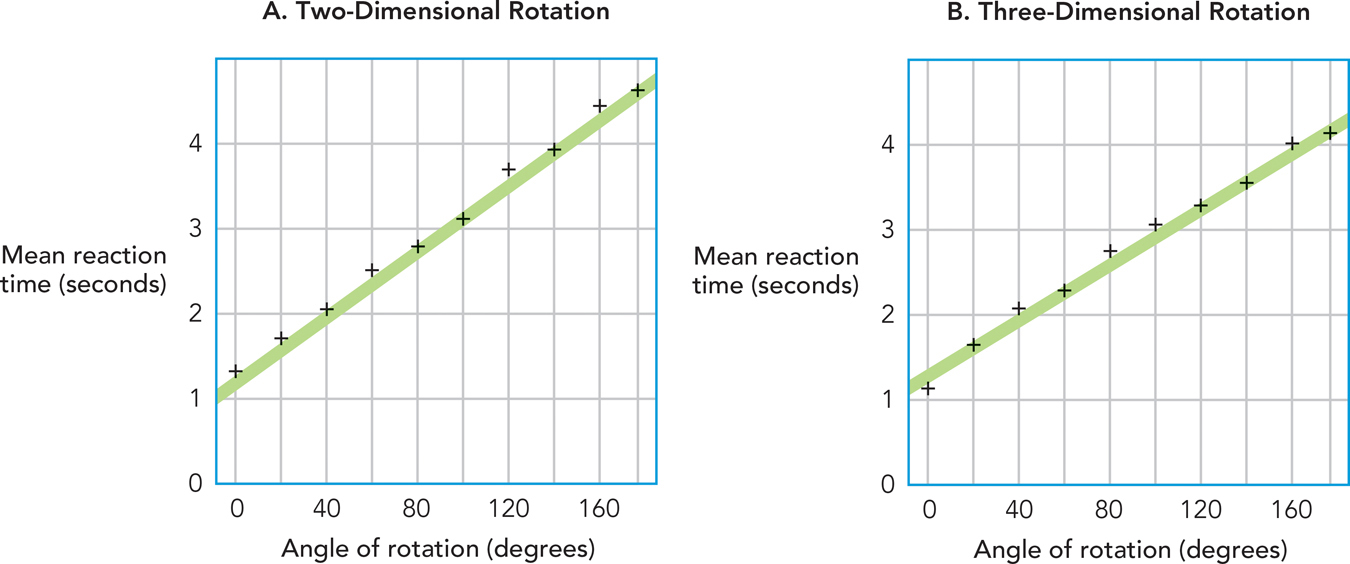

The study produced startlingly precise results. The time needed to rotate mental images correlates almost perfectly with the number of degrees through which the image has to be rotated (Figure 8.10). Compared to a 60° rotation, people take twice as long to rotate blocks 120° and three times as long to rotate them 180°. This is true whether blocks are rotated in the plane of the picture (Figure 8.9a) or in depth (Figure 8.9b). Either way, people mentally rotate objects at about 60° per second.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 22

True or False?

341

Mental Distance

Preview Question

Question

What does research on mental distance suggest about how we use mental imagery?

What does research on mental distance suggest about how we use mental imagery?

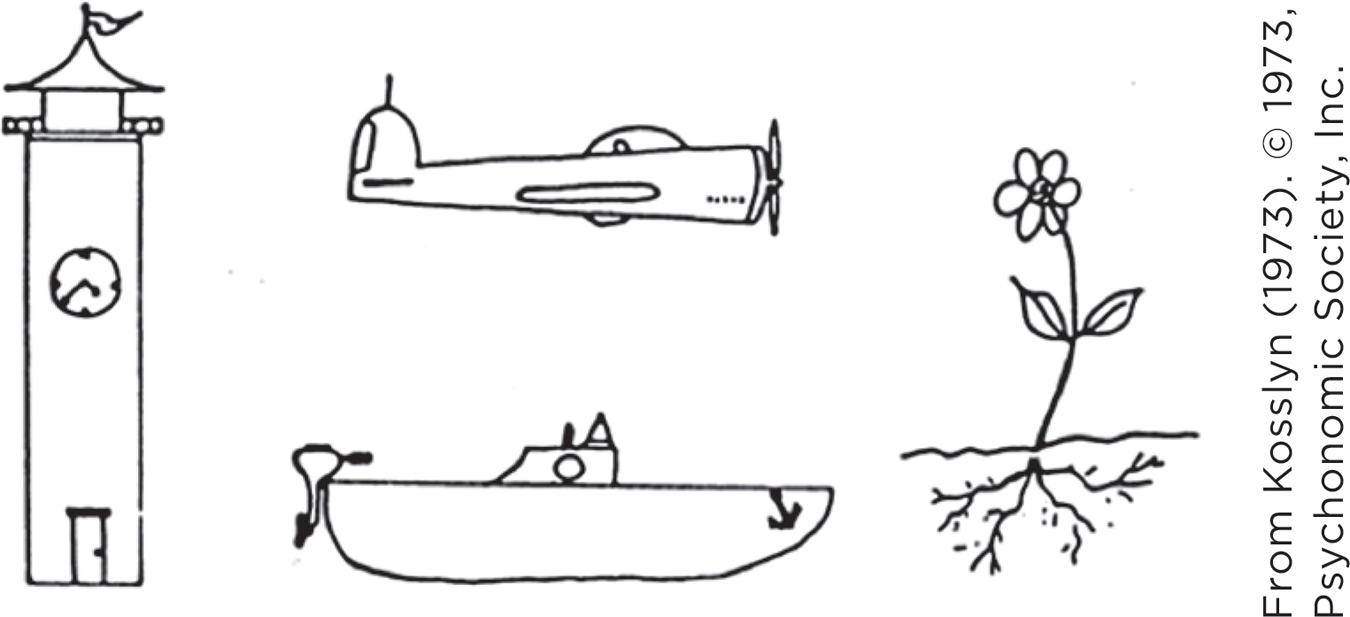

Research by Stephen Kosslyn (1980) complements the mental imagery studies of Shepard. Kosslyn showed participants the pictures displayed in Figure 8.11. After participants formed a clear, accurate image of each one, Kosslyn took the pictures away and asked people questions about the objects that were pictured, for example, “Did the speedboat have an anchor?” Again, the time taken to answer was the dependent measure.

Before asking the questions, Kosslyn instructed participants to “mentally stare at” one end of their mental image (Kosslyn, 1980, p, 37). In different experimental conditions, they stared at either the left or right side of the boat, or the top or bottom of the clock tower. The instructions thus varied the “distance” between (1) where people stared and (2) the object about which they were asked a question—

Some theories would have difficulty explaining Kosslyn’s results. For example, semantic network models (Chapter 7) suggest that people store information by linking together facts that are represented verbally (e.g., facts such as “boats” have “anchors”). In a semantic network model, the instruction to stare at one versus another part of the boat wouldn’t be expected to affect the links between stored facts. Kosslyn’s finding, that the instruction did affect people’s speed in answering questions, thus suggests that people were not relying on verbal facts alone, but on mental images.