9.2 The “What” and “Who” of Consciousness

Step 1 in the study of consciousness is to identify what it is. This can be done by recognizing consciousness’s defining features.

Consciousness: What Is It?

Preview Questions

Question

What does it mean to say that consciousness is “subjective”?

What does it mean to say that consciousness is “subjective”?

Question

What psychological quality must something have in order to say that it has “consciousness”?

What psychological quality must something have in order to say that it has “consciousness”?

Consciousness has two defining features: (1) It is subjective, and (2) it involves more than the mere detection of stimuli in the environment.

SUBJECTIVITY. Consciousness is personal. It exists, and must be assessed, from the perspective of the individual person—

In this respect, consciousness is relatively unique. Many other personal qualities are objective; that is, someone observing you can provide an independent, unbiased view of those qualities. This is not true for consciousness, however. An example illustrates the difference between subjective experience and objective facts.

Sometimes, as a result of injury or surgery, people lose a limb. More than 90% of these people experience phantom limb syndrome, the subjective conscious experience that the amputated limb is still attached to their body (Ramachandran & Hirstein, 1998). They often experience pain in the limb—

The amputation is an objective fact. Someone other than the patient can assess whether the limb is still attached. If a patient claims, “Doctor, my limb is actually still attached,” the doctor can check the true state of affairs and say, “Sorry, you’re wrong; it turns out that it is not attached.” The pain, however, is subjective. If the patient says, “Doctor, I’m in pain,” there is nothing for the doctor to “check” to verify the statement, and it would make no sense for the doctor to respond, “Sorry, you’re wrong; it turns out that you are not in pain.” The patient is the one-

364

This is what it means for pain, and other conscious experiences, to be subjective. Such experiences occur, and can be verified, only from the point of view of the individual conscious subject.

MORE THAN MERE “DETECTION” OF THE ENVIRONMENT. The second feature of consciousness involves a distinction between (1) detecting and responding to events, and (2) feeling something after the event is detected.

Many organisms and human-

These objects detect and respond to events yet are not conscious. To see this, compare your experience on a cold day to that of the thermometer. Like the thermometer, you detect frigid temperature and say, “It’s, like, 5 degrees out here!” But you do something the thermometer doesn’t; you experience the cold. You feel what it “is like” to be out in the frigid temperature. That’s not true for the thermometer. Except as a joke, you wouldn’t say, “I wonder what it’s like for my poor thermometer to be outside on such a cold day.”

This simple example makes an important point. Consciousness involves more than just detecting and responding to events. It involves feelings. The scientific study of consciousness is the study of what it feels like to be a conscious being (Chalmers, 2010).

Now that we have learned what consciousness is, we can devote the remainder of this chapter to the main topics in the study of consciousness: the question of which beings have conscious experience; psychological and biological processes in consciousness; the dreamy alteration in conscious experience that is sleep; and alterations in conscious experience caused by meditation, hypnosis, and drugs.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 2

Though amputation is an objective fact, the pain of /Wiy8JSVkDQPfT+H limb syndrome illustrates that pain (and consciousness) is a yzVIan6Sa7+EHdYQePyf2g== experience.

Question 3

09kp0IMF5tNYHJyYBvkAeMdcUaDibTxv01366UiT1WK9KhvYetkP0sXUNU9u1SR5L3Tsf1dEvO3e6c0SRc9CehoBq3M0JNQqvb157c73rEDC+GbQDYERtT/KaqDLDzCJ5BYTsMXCkpWb91AAaz94H0/wRVIv4rTw2QA/Xg+jC8g=

Consciousness: Who Has It?

Preview Questions

Question

On what basis did the French philosopher René Descartes declare that consciousness is a basic fact of life?

On what basis did the French philosopher René Descartes declare that consciousness is a basic fact of life?

Question

When, during development, do humans first experience consciousness?

When, during development, do humans first experience consciousness?

Question

Do animals have consciousness? How do we know?

Do animals have consciousness? How do we know?

Question

Do animals have self-

Do animals have self-

Question

Why don’t robots have consciousness?

Why don’t robots have consciousness?

Earth is home to billions of creatures. It also houses billions of man-

365

PEOPLE. The one being that you can be sure is conscious is yourself; you know that you experience the world. Your own consciousness is a basic fact of life.

The French philosopher René Descartes made this observation about 400 years ago. He was searching for a secure basis of knowledge—

Descartes judged that the only fact of which he could be certain was the fact of his own existence and conscious experience. Even if he tried to doubt it—

You can engage in the line of thinking Descartes pioneered and easily conclude that your own consciousness exists, too. You’re likely not alone. One can entertain the thought that “I alone exist; everybody else is a figment of my imagination.” But we will ignore that unlikely possibility and presume that all biologically normal humans possess consciousness. When asking, “Who has consciousness?” you confidently can answer, “people.”

What is it like to have consciousness?

Human consciousness is pervasive; it occurs almost all the time. When awake, you’re generally conscious of your surroundings, your feelings, and the thoughts running through your head. When asleep, you spend much of the time dreaming, which is a form of conscious experience; although not awake, you are experiencing the vivid, sometimes weird images and storylines of your dreams.

There is another sense in which consciousness is pervasive: It starts early in life and persists throughout the life span. Some evidence suggests that humans have conscious awareness before birth. Third-

Studies of infants complement this research on fetuses. When adults become consciously aware of a stimulus, they display a distinctive pattern of brain activity. A similar pattern of brain activity in response to stimuli has been observed in infants as young as 5 months old (Kouider et al., 2013). This finding further suggests that conscious awareness is evident early in life.

THINK ABOUT IT

Descartes said, “I think, therefore I am” (i.e., “Therefore, I and my conscious mind exist”). But you could program a computer to say, “I think, therefore I am.” Does that mean it would exist, with a conscious mind?

This capacity for consciousness usually lasts a lifetime. However, people sometimes lose it. Injury or illness can extinguish conscious experience, as you saw in this chapter’s opening story. Researchers did identify a person who had been diagnosed as being in a persistently vegetative state—

366

NONHUMAN ANIMALS. How do we know that nonhuman animals are conscious? They appear to be conscious; your dog seems excited when you arrive home and tired after she runs around in a park. But appearances could be deceiving. A motion-

There are two types of evidence. One is behavioral. When animals perform tasks, they are distractible in much the same way that people are. Researchers observe that animals sometimes lose track of important information (e.g., the location of offspring) when engaged in an activity unrelated to that information (e.g., obtaining food for oneself; Baars, 2005). The parallel between human and animal distractibility suggests that both human and animal mental life consists of conscious experience of limited size. We and our furry friends can focus on only a small amount of information at any given time.

The second source of evidence is biological. The brain systems needed for human consciousness (see below) exist, in quite similar form, in mammals other than humans. This cross-

How can you tell if an animal, such as a dog, is distracted?

When discussing animal consciousness, it is important to distinguish consciousness from self-

You can have conscious feelings without self-

Few animals show any sign of self-

How often have you engaged in mental time travel today?

Even nonhuman species that pass the mirror self-

367

CONNECTING TO BRAIN SYSTEMS AND PERSONALITY PROCESSES

In sum, then, humans have a unique form of self-

Not all animals have consciousness, however. Many simple organisms, such as insects or worms, lack the brain systems required for conscious experience. They detect and react to events in the environment, but scientific findings provide no firm grounds for concluding that they have conscious feelings. Some argue that even fish, a relatively complex class of organisms, lack the brain structures required for conscious feelings. Analyses of the nervous system of fish suggest that they merely react to the environment reflexively, experiencing neither pleasure nor pain (Rose, 2002).

ROBOTS? If you walk into a Honda office in Japan, ASIMO, the receptionist, will stroll up, say hello, shake your hand, and show you around the place. ASIMO will answer simple questions and, with some practice, may even learn to recognize you the next time you stop by.

This wouldn’t be all that impressive for a flesh-

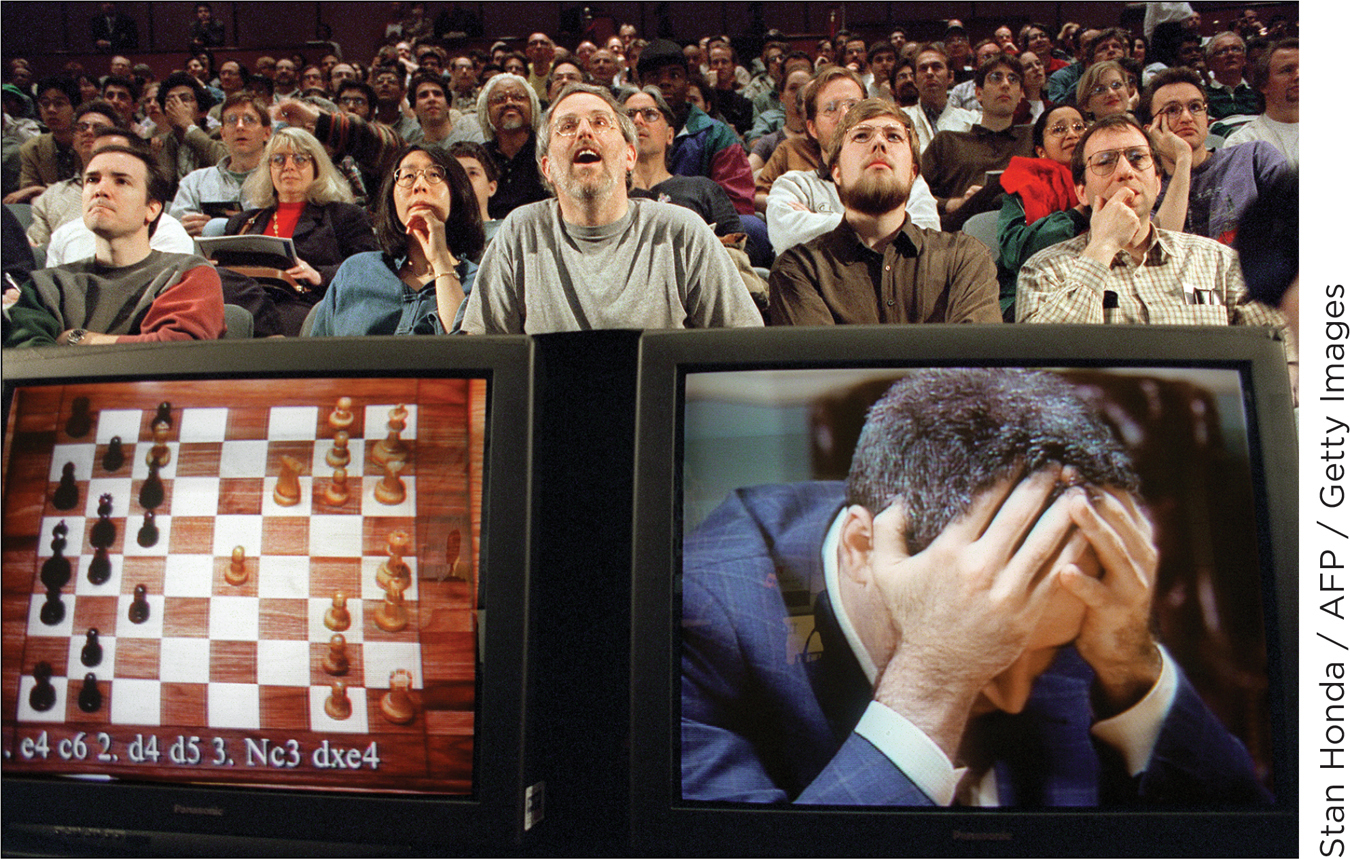

Is ASIMO conscious? It certainly looks like it. If something walks up to you, shakes your hand, and answers your questions, it would be reasonable to guess that it is conscious. Yet ASIMO surely lacks consciousness. So do his electronic relatives: computers, smartphones, chess-

368

Information processing, by itself, is not sufficient to produce conscious experience (Chalmers, 1996; McGinn, 1999; Searle, 1980). Information processing is merely the manipulation of symbols (numbers or words) according to logical rules. Consciousness is different; it involves not only symbol manipulation, but also emotions, sensations, and other feelings. In fact, logical reasoning is not even necessary for conscious experience. An animal bitten by a predator experiences pain immediately, prior to engaging in any steps of information processing to determine, for example, who the attacker was.

Present-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 4

Descartes’s famous quote “I think, therefore I am” conveys the idea that the only thing about which we can be certain is our own Y+2pf4SnAU+DY2faCkh+n6PkWVM=. Consciousness exists even before we are xDswOSAPh2rtIjem, as illustrated by research with fetuses who could detect differences in sounds.

Question 5

t7045DXkrFRiRbfQloGUfnLhip8Ft8taYeJ4O07eFmLEUCRN7+jg0slVNjdndIY/s3g+AZLmjO0qaKiACOT+YCAD85Dbl9blEzT5G+ANWZdRLMDCBOOTujNl+ITzZbnVMiAaVA==Question 6

uHhxYC7Ha26NAZnBd0MEMp38ZLOjtJTMshqVVcsyP3gMTfYNTcQLE0+iauBdt0c5M6rK4Adfy1LGpQcvDCe75sxIEjrMkqy/wTl7jdNo5tAYCkYK819eMXpXPEJc04oko5z9dfT3hsQTuX5Rtja7nQTToJu3qDT1BEuphE3kgUMkbh3rB8ZgOXp6/RsnUjEbAy5vjpwXZ+YAYjyBv5rvDTRplInHhCn6xkQqj0thhz7rUFxu3S8G6lbjjLY=Question 7

A robot can manipulate symbols according to logical rules, but because it doesn’t experience RLnNeubx309/QjNRS0pyMrBuyRRDtJDA, it cannot be said to possess consciousness.

I’m afraid. I’m afraid, Dave. Dave, my mind is going. I can feel it. I can feel it.

—HAL the computer, 2001: A Space Odyssey