9.3 The Psychology of Consciousness

Our discussion of people, nonhuman animals, and robots shows you what consciousness is: the ability to feel events—

Dualism

Preview Question

Question

Is the mind separate from the body?

Is the mind separate from the body?

Dualism is a theory about the mind, the brain, and conscious experience. Dualism proposes that mind and body are two separate entities. The body is a physical, material object, whereas the mind is nonphysical—

369

Dualism is an ancient belief. Buddhism, some philosophies in ancient Greece, and Christianity all posit a mind, or soul, that is distinct from the body and lives on after the body’s death.

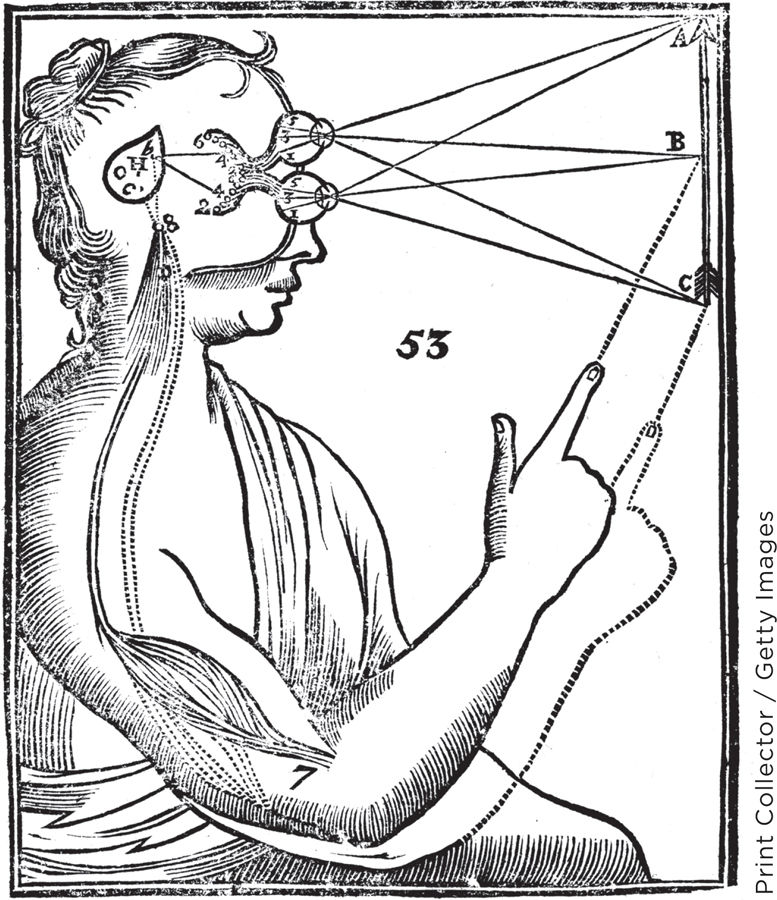

In later Western philosophy, the most famous dualistic view was developed by Descartes, whose ideas we discussed earlier in this chapter. He proposed that the mind and body interact at a specific spot within the brain: the pineal gland (Figure 9.1). Why the pineal gland? His reasoning combined two ideas:

Descartes believed that there must be one spot—

a single location— in the brain at which information from all perceptual organs (eyes, ears, etc.) comes together. This spot is like a “theatre” within the brain. For example, at a movie theatre, sounds and images must be projected to the same place, so you can experience them together. Analogously, Descartes thought the sounds and sights of the world are projected into one spot in the brain. Descartes knew the pineal gland is biologically unique. Other brain structures come in pairs, with parallel structures in the brain’s left and right sides (see Chapter 3), but there is only one pineal gland. He thus concluded that information was projected there.

THINK ABOUT IT

Is dualism testable? Or does its claim that consciousness is a property of a nonphysical mind—

In Descartes’s dualism, the nonphysical mind views the images in the pineal gland, makes decisions, and directs the body’s actions by affecting mechanisms in the brain.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 8

For each of the “answers” below, provide the question. The first one is done for you.

Answer: A theory claiming that consciousness is a property of the nonphysical mind and that the brain is where the mind and body interact.

Question: What is dualism?

- /fUTA7htLni8JQYDXifbCQrpB/eNfMNYXF+iJBhuV60AYWtyeO+99VJE8OhDlU5l6QZecny/sJ+FhJ9gBB/YDQ==

- AlEBLU2naRyeWmjiBg9UczPVld5RrdollhMJ265ZFhNOSp1sNR7XYQwCRyWTD+2tBrIH4q4cA5DcvrZBxuGPVFGp2gwNUtduJZg2hV/6aA6cuDVlmw0Q30BLsvnWT1LUG8gG2hGoamvsk04GFFEnM9tV92FpQLwLgzJ0yAKwjJ5aeEQu//SPempX5uY=

b. Who is Descartes? c. What is the pineal gland?

Problems with Dualism

Preview Question

Question

What are some limitations of dualism?

What are some limitations of dualism?

Today, scholars recognize that dualism is deeply flawed (e.g., Dennett, 1991). Two problems stand out: the mind–

THE MIND–

In saying this, dualism encounters the mind–

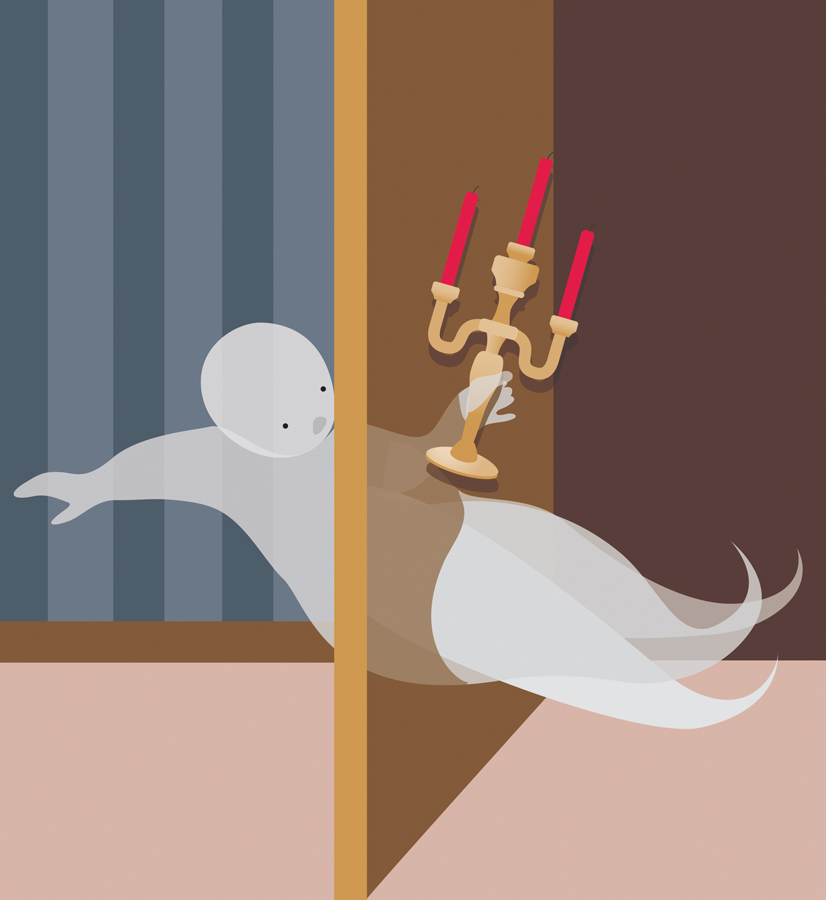

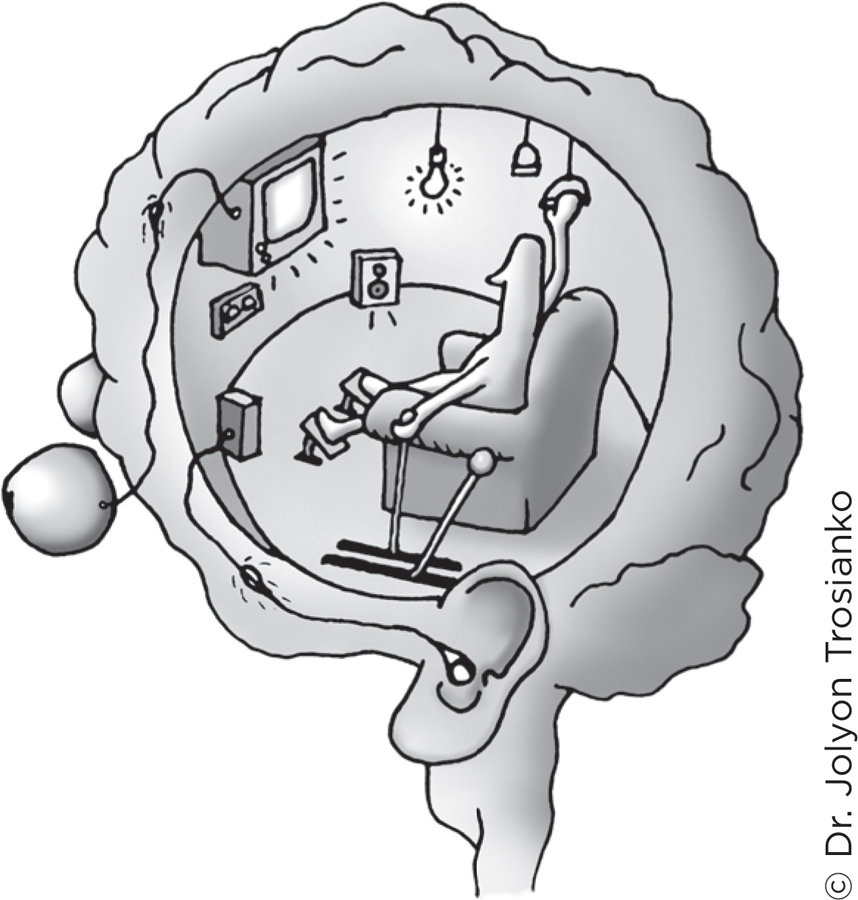

THE HOMUNCULUS PROBLEM. The homunculus problem is a problem in scientific explanation (McMullen, 2001). It arises whenever a theory states that a structure in the mind or brain has conscious experiences. That structure is like a small conscious person-

What’s the problem with a homunculus? If a theory claims that people are conscious because a structure in the brain is conscious, it does not solve the problem of consciousness. It merely introduces a new problem to be solved: Why is the structure in the brain conscious? The cartoon here illustrates the problem. If Descartes says that “the person whose brain is shown has consciousness thanks to the homunculus, who consciously experiences sights and sounds displayed in the brain,” then he has not explained why the homunculus has consciousness, and so has not provided an explanation of how consciousness occurs. Saying that “the homunculus has, in his brain, an even smaller homunculus” clearly does not offer any serious progress in explaining how consciousness works.

THINK ABOUT IT

When you hear a scientific explanation, think critically. Suppose someone says, “Water is wet because it is made of wet molecules.” Once you think about it, you see that this is no explanation at all; it does not explain why the molecules are wet and thus does not explain wetness (see Hanson, 1961; Nozick, 1981). Similarly, saying that “people have consciousness because information in the brain is perceived by the conscious mind” does not explain why the mind is conscious and thus does not explain consciousness.

371

A challenge for psychology, then, is to build a theory of consciousness that does not run into the mind–

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 9

lrIrUvAPUv1gzoZ5/TZMdRZLTW1BMmyJAtL2R6jhLHlO1gSpqpoymffQnHCvsCrAgeD6XspNeAPo5GHZ7j5PfUxIIb1nHzK+51SmlewgldudHlQezsBKRSSRnRQJVh8+0garx6zl/UXEEdpyIBYGTgHjhOyYhn+rcAHWT3JG0WKwea4YyEHBvHPUxaIMKhAJBdE4sX01liWlqBZEZUvmoJIR91Kf8QvW0BTO8WaRGtm5/ZUqKdHZ+4IEmoYWhEFeu9xBRkheqS5CfzwsQOqU5yXQuCQRvni4ECRFQxuv0SBPkLHudVJhLmsuktGxvxwQKRtPwrXy7GB14ALUOCqIiybxZrMIMGC86G4bVHEJEQglCyl+D1gPWocIcOmrb/freYAgezkut1Zb3mq7TQfGrL9WqlCfZOTFNA9JLz9INky3PlcL01D6jV9OAKPkm2r80KoLOqDAbx6WB9+VTNEwWbw5yCJBMNENgqbFk8fHYucoWMlYeqfLV1ogLBavLLMJUQeSkyT1CFBIZrMz/LxNii7pf876oI18Question 10

+iQr3QzSAvg4IldQAs56cfmiKahbSzgZc74/a1e+0xXXCkZuoxioCWxdnsc7x2i6KndyDfEGxfqXgtB2JosVED/zCzKkQh+EYd32BgX+30+Kzcd+41sMfQ1bSujGsAVRXbJc0DgBkDIBPtIriT0HOKTNDp5UTsvvaSvjXOkE1Nhik5rW4s8LC+rS5gXvbl8r+BRrTNQTaqZs7U9EionUiw4OaaZQDWvWB/P+2WD9Z3QpaGJ1V6yypWsM6uzdY3zPJJh8VXL7Bb+MUUWyRfxr4rL4uRdPyQbn68KxkJ8IfrAUL+RkdlNWJZNE2OZ9oq7ekHwGndCheyS6X/5S6od2WMs1aoPOJadq7fDXnbYbbrsl8355uFYAOcQK/ZaYU720RZB+f8dzuePFCc0pxBduI9FdncFN10p4O3qfRIS40C6XOp8EJNxG5YNzK81ljaj7wVqUi5n3dnrTvutJb8ulO5k4Upe5r046QjQwD/CKSKEb65552Poj+LHcEsMLHM61wBN6kZHjnRRMU8MCRE8cuwzjg9Yg1Qi5ymfPgC6OUNHVEiYpK12oWmCiX7PMHMOJXPfh4xDqQG7FMic6NxR3gMZHPHSVgKuK“I understand that you believe the world rests upon the backs of four white elephants. Is that correct?”

“Indeed, this is so,” replied a holyman.

“Now tell me, just what is it that stands beneath the great white elephants?”

“Under each of the four,” the sage replied, “there stands another great white elephant.”

“And what is beneath that set of elephants?”

“Why, four more elephants.”

“And what is beneath that set…”

“No need to keep asking. It’s elephants all the way down!”

—from “World-

Overcoming the Problems of Dualism

Preview Question

Question

How can one explain consciousness without proposing that the images of the outer world are reproduced within the brain?

How can one explain consciousness without proposing that the images of the outer world are reproduced within the brain?

One theory that avoids the problems of dualism has been proposed by the philosopher Daniel Dennett and his colleagues (Dennett, 1991; Dennett & Kinsbourne, 1992; Schnieder, 2007). The theory has three main features.

The first feature involves the distinction between two potential activities of the mind: reproducing a stimulus in the environment, and detecting a stimulus in the environment. In Descartes’s theory, the brain reproduces stimuli; it essentially creates a picture of the world within the head. If a red arrow appears in front of someone’s eyes, the person’s brain reproduces the image (see Figure 9.1). Dennett realized, however, that to explain consciousness, you do not need to propose that the mind reproduces stimuli. Instead, it may primarily detect features of stimuli and, based on what it detects, make “educated guesses” about what is in the environment. If a red arrow is placed in front of you, different parts of your mind detect different features of this stimulus: its long shape, pointy top, color, orientation (pointing up), and so on. Once a few of these features are detected, you can infer—

The second feature involves time. Dennett explains that different parts of the brain take different amounts of time to do their work. A brain mechanism that detects shape, for example, might work faster than one that detects color. This means there is no single place in the mind—

Finally, in Dennett’s theory, there is no homunculus. No single part of the mind observes images and makes decisions. Rather, consciousness is based on the action of large numbers of psychological processes that occur simultaneously, in fractions of a second. These multiple processes each contribute to interpretations of what is happening outside the mind, that is, to conscious experience of the world.

372

Dennett is not the only contemporary theorist to formulate a theory of consciousness. Others have proposed that consciousness consists of a “workspace” with connections to different regions of the mind that process information simultaneously. The connections enable the mind to combine information of different types (Dehaene & Naccache, 2001). Consciousness results from the overall pattern of connections, not from a single homunculus.

These contemporary theories have an interesting implication. They imply that when you shift levels of analysis from mind to brain, you should not expect to find any one brain structure that independently produces consciousness. Instead, Dennett’s theory—

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 11

Identify whether the statements below were more likely made by Descartes or by Dennett.

- 9bhqKeUgpyt+ntkyeD6aFT8jCZPsMblNBdmPiKAFrXmnM1aT/azoLs0pjbvjMAunr/sx10kwQADLCCHVE+roY79iCXOU3h8DgW/59Mc/r4HgHWQNNW7j8Xqr8+pIrzYWOV47JV4ECMbnVyEFJLoW+ntiCuA9IXlTv7rx09PUxXK6p7SD0uR+/QsLgtgVkp+OgZm+A3aLi9f6y12jG0WaCIABPms=

- ufVFOg2nyEWQZ8z/bRSaxayBKae8Gfdx4jru1+TAsfBaYYSjEaRKklyCQUgcaB+PgGZZ2C4sxoq8oNR8bRncOAuEQrDUM4RCSP4xeHMyeCTiqWCenLTYDjGhk6eEgtJNEyKdgQFwVXqikvmcNI07QVzjCmy/3RBLQaXwfzsljyt/L+rLIl6zJDVdLB3WQEFF

- 3Z0IaAlGe0GhGAh5Kci2p7wC1/OP7qu5P9CD8D+rNHgl5amY0QCsy0djwoPAnWAbU4Alf5Cj/2wT3w+Dtq0Hnk++otXCx2x9VpO+9Fc1wQFZWDpzMMNxBjuIW9JPsRK0WMRD+MahzusrE/bcm5hh7MsD5KeFgMKEXhLk6rs9xEAAoMxat+0r87QZNpZDoscd

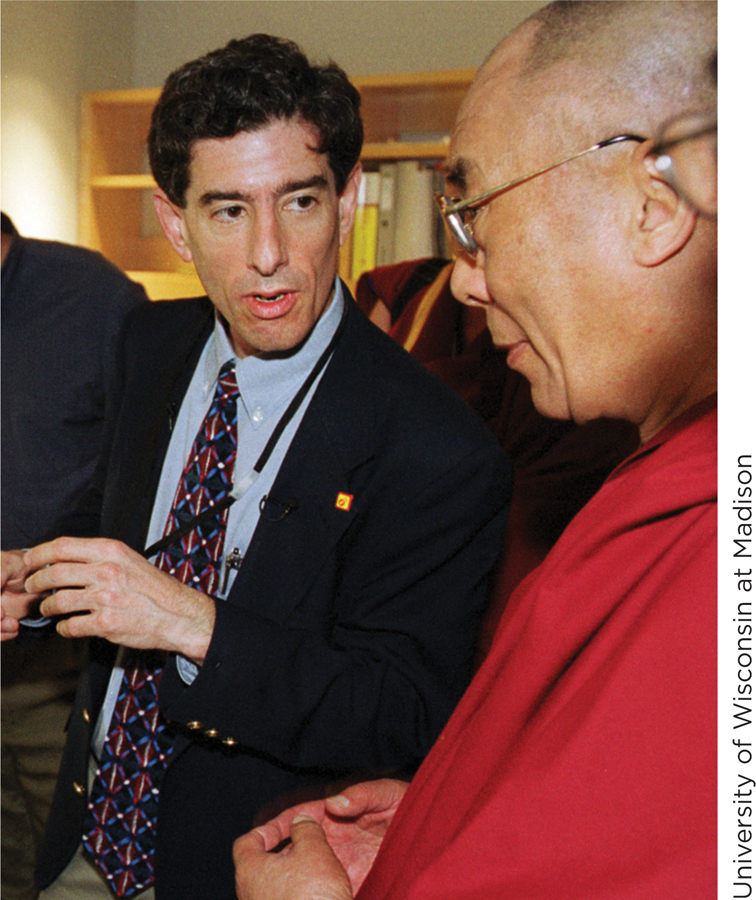

CULTURAL OPPORTUNITIES

Eastern Analyses of Conscious Experience

Theories developed in “the West” (Europe and America) inspire most contemporary research on consciousness. Some of them were developed recently, whereas others, such as Descartes’s, are centuries old. Yet all these Western conceptions are relative newcomers compared to theories of consciousness developed in the East. Particularly noteworthy are Buddhist and Hindu conceptions originating in South Asia (especially the region corresponding to the contemporary nation of India) more than 2000 years ago.

Like many current-

The first difference involves the role of the body and brain in consciousness. Virtually all modern theories presume that consciousness arises entirely from brain activity (Searle, 1998). Ancient South Asian scholars, however, judged that it reflected the activity of not only the physical brain but also “an extra-

Second, Eastern theories recognize a wider variety of conscious experiences. Western theories tend to focus on a relatively small number of phenomena: conscious awareness, mental states during sleep, and perhaps variations in positive and negative mood or a small set of emotions (anger, sadness, happiness). Eastern scholars, however, distinguished among an enormous variety of conscious states. For example, the Buddhist Asanga, writing in the fourth century BCE, differentiated eight types of consciousness, variously based on sensory systems and personal knowledge (Dreyfus & Thompson, 2007). Other Buddhist texts identify negative states—

373

Finally, Eastern traditions are unique in identifying a series of jhanas, which are varying states of mental concentration that can be achieved through meditation (Goleman, 1988). At first, meditators experience sustained attention, awareness of bodily states, and a feeling of bliss. Gradually, they achieve a state of serenity in which there is no conscious awareness of bodily states and no feeling of pleasure or pain. Eventually, the meditator attains a jhana in which the mind is cleared of all normal conscious states.

Even though they were not scientific theories in the modern sense of the term, Eastern analyses of consciousness deserve attention. Through careful description of conscious experiences, Eastern scholars carried out a task that is critical to good science: describing the full range of phenomena that scientific theories ultimately must explain.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 12

Which of the following statements about the differences between traditional South Asian theories and modern psychological theories of consciousness are accurate?

- QvJQYiyQdvZUJ58bmlMxG6PaKFZaVBauD80gDMWz8VkNtgqnTuvaW090GsBZ+zPZDsqBCpqWtNYPPxgiTn8riZXc5NFOCi3pmI2xb96L6hC0RdEcoIKIsYBE7WJpzJdJB3k6oN1tPc/lE90k23xFjq/jLcoJj/1TT+EHlKNkbgV6ybnS3jGjdt6rXAY=

- 9aw0Sjt8UZ7vn8ym7qgmCfOVYKTjRFTavi8JtHu2Uk6p4cf7dIEoYGznMt/xs0AigvWnoQy8DJ/Mjyr4jP8jXYAaAPwIn94TpM1j6SibqcFg8wnfSvBKJWU1xfEH+CA3NVCQt3F/Hy4sCsuiboDOh2xExIcGs9DxfQqIGwgmHa1WX9ZH0uFsEpWpzCJRGwiRHWWi5x0sFXCUNaZaQu8iW7HljkyI2ZXPCchnU+dNNhyANnVOFFa+CAIU54cDFbSdpS0yW3ZWFfg+H8bBkPSPZVmzZuTJTxeNSxJ+OYCIHcxc6ldtUZCTXnT1smJgWb3Jw7jYgH8s9eT9x3PMVJt8SJs8YudVP/jSkA6WJNMRrznlQzcbles/NISGPtuoP/AMUFojv0Iu2v5tVNpWnpMHaTlJYIo=

- +tXotapZuqKjdR4U2R7epScz4pH090nEmIOhgzOwDjHJImdLq4U/jL8j170iBldAfbuoj00zMfLlH4pHN9sWtQ84UlJhso/5LyucnutLhvq/FTDYJ3wYOQvMXDY7NTeN6MFGkGO7MxRytKm1/S/ettORWN0TkLXbtPQ8zDZ179Kz63Fu57isgt1XzDT+HxA+aJkAIrNXgp6XmqTRztBsN5epEvT+5WcMUcC+AXYw38t1vyooEVKnAMZjINoAw/T/HxTxcNfx9J6fhIaHpbEEoRUA7Qioj2NF8hALM3I7mgK3Mc6tBcgAWTuxP7swagpuPxQ24vuF4OY=