10.1 Defining Emotion and Mood

Let’s begin by defining our terms—

Emotion

Preview Question

Question

What are the four key components of an emotion?

What are the four key components of an emotion?

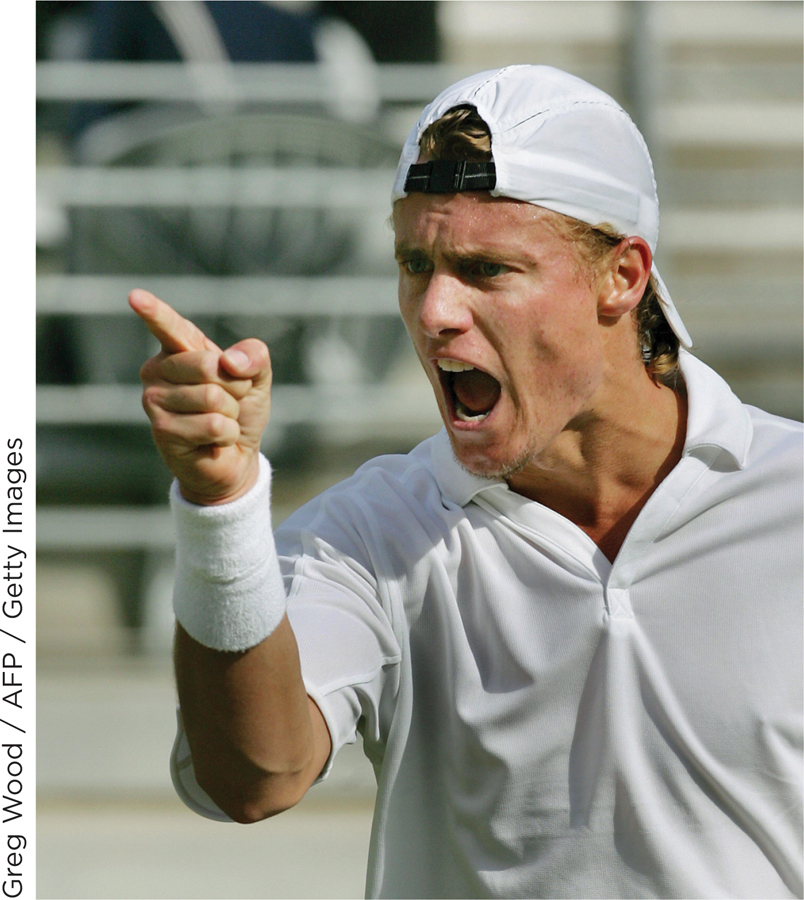

What is “emotion”? Let’s see how people use the term. In English, “emotion” describes psychological experiences with three components: (1) a feeling (if you say that you’re experiencing an emotion, you’re inevitably feeling good or bad), (2) a thought (when experiencing an emotion, such as sadness or anger, you usually are thinking about the person or event that caused the emotional reaction to occur), and (3) bodily arousal (your physiological state is different than it was before the emotion occurred; Wierzbicka, 1999). Here’s an example. Suppose a driver cuts you off in traffic and you experience an emotion: anger. The emotion includes the three components:

Feeling: Once your anger kicks in, you feel different than you did moments earlier.

Thought: You’re thinking about the other driver; you’re angry at him because he almost got you into an accident.

Bodily arousal: You’re more aroused, physiologically, when angry. People may describe the physiology of anger with phrases such as “I was steamed” or “He got my blood boiling.”

If one of these components were missing, you would not say that you were experiencing an emotion. For example, suppose #3, bodily arousal, had been absent; perhaps you responded calmly, merely uttering soft-

In addition to these three key components—

If someone were to see your face right now, what emotion would they detect?

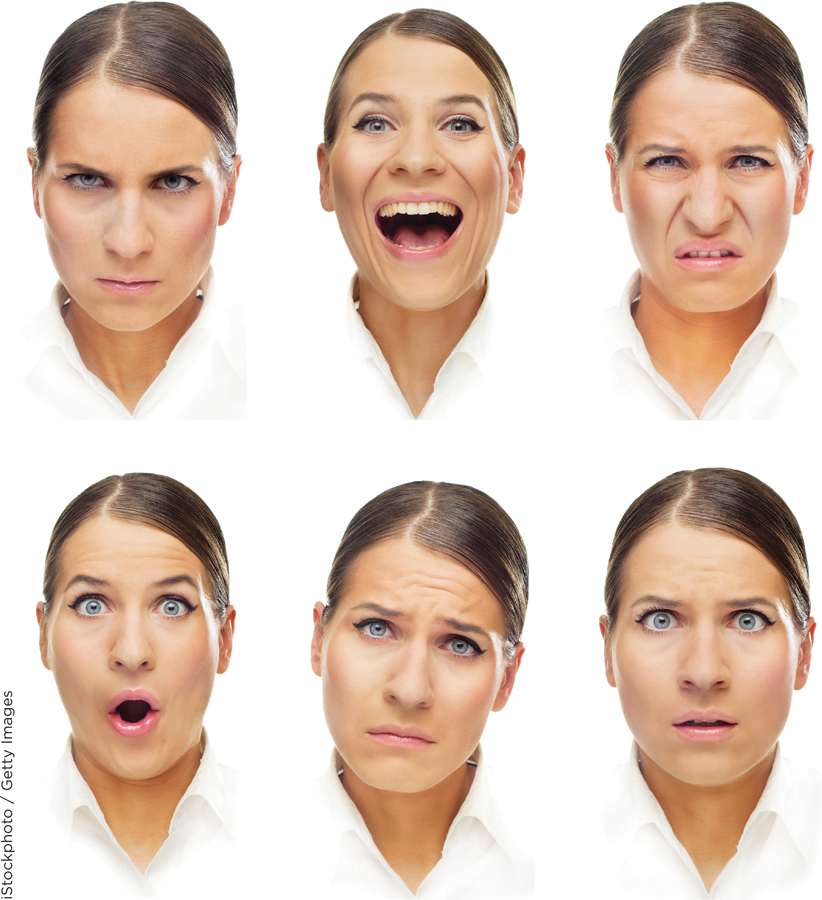

Not all languages of the world use the word “emotion” in exactly the same way (Wierzbicka, 1999). Yet, for our purposes here, the way you naturally use “emotion” in English suffices to define the term. An emotion is a psychological state that combines feelings, thoughts, and bodily arousal and that often has a distinctive accompanying facial expression.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 1

Imagine that while you were out walking one day, you witnessed an act of kindness: someone helping an elderly woman cross the road. You momentarily felt different than you had prior to seeing this and thought to yourself, with a smile, “I’m so glad there are helpful people in this world.” What question do you need to ask to determine whether you experienced an emotion?

Mood

Preview Question

Question

How do moods differ from emotions?

How do moods differ from emotions?

You already know that moods differ from emotions—

Moods last longer than emotions. Although emotions vary in duration, some lasting for seconds and others for hours (Verduyn, Van Mechelen, & Tuerlincx, 2011), they tend not to be as long-

lasting as moods, which can last for many hours or days. Moods are not necessarily accompanied by a specific pattern of thinking (emotion component #2, above). You might be in a “bad mood” or “peppy mood” without knowing why; you can feel “moody” without being moody “at” or “about” something. By comparison, when you are emotional, your emotion is directed toward some person, object, or event (Helm, 2009). You’re angry at someone, jealous of someone, or guilty about something.

Moods are not strongly linked to facial expressions. People’s moods may not show on their faces; you could be in a low mood without anyone realizing it when looking at you. Moods, unlike emotions, do not trigger the distinctive facial displays shown in Figure 10.1.

Mood can thus be defined as a prolonged, consistent feeling state, whether that state is positive (a “good mood”) or negative (a “bad mood”).

How has your mood been lately?

With these definitions in place, let’s now look in detail at the psychology of emotion.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 2

Mood or emotion? Specify whether each of the following statements best describes a mood or an emotion.

“Abbie always gets a little depressed during winter, though she can’t really tell you why.”

A. B. “Barney’s work colleagues remark that no matter how stressful things are at the office, he remains typically very upbeat.”

A. B. “Candida visibly blushed when realizing she had addressed a new acquaintance by the wrong name during the whole party.”

A. B. “Deshawn was overcome with joy at his surprise 21st birthday party, a joy that was clearly visible in his wide smile.”

A. B.