10.2 Emotion

The history of research on emotion is somewhat unusual. For much of the early and mid-

Starting in the late 1950s, psychologists began to develop methods for studying the mind (Gardner, 1985). Yet emotion continued to receive little attention. Most psychologists of this era viewed the mind as an information-

Some psychologists bucked these trends. Silvan Tomkins (1962, 1963) developed a theory of emotion that drew on the evolutionary biology of Charles Darwin. Richard Lazarus analyzed ways in which people can control their emotional reactions (Lazarus & Alfert, 1964). But these were minority voices; emotion—

411

In the last quarter of the twentieth century, the scene shifted. A set of intriguing research findings drew psychologists’ attention to emotion. Investigators found that emotions can directly influence thinking processes. Other researchers identified brain systems that give rise to emotional experience. Research on emotion and culture revealed that some emotions occur in all cultures, whereas others vary across the globe. In total, this diverse set of findings—

In fact, the field has become so large that organizing it is a challenge. We will do so by posing four key questions that today’s researchers seek to answer. The first is “Why do we have emotions?”

TRY THIS!

Before you start reading the material on why we have emotions, experience for yourself one of the research tasks that researchers use when trying to answer this question. Go to www.pmbpsychology.com and take part in Chapter 10’s Try This! activity. We’ll discuss it in the upcoming section of this chapter—

Why Do We Have Emotions?

Preview Question

Question

What are four psychological activities that we can accomplish with the help of emotions?

What are four psychological activities that we can accomplish with the help of emotions?

Could life exist without emotions? You can imagine it. Science-

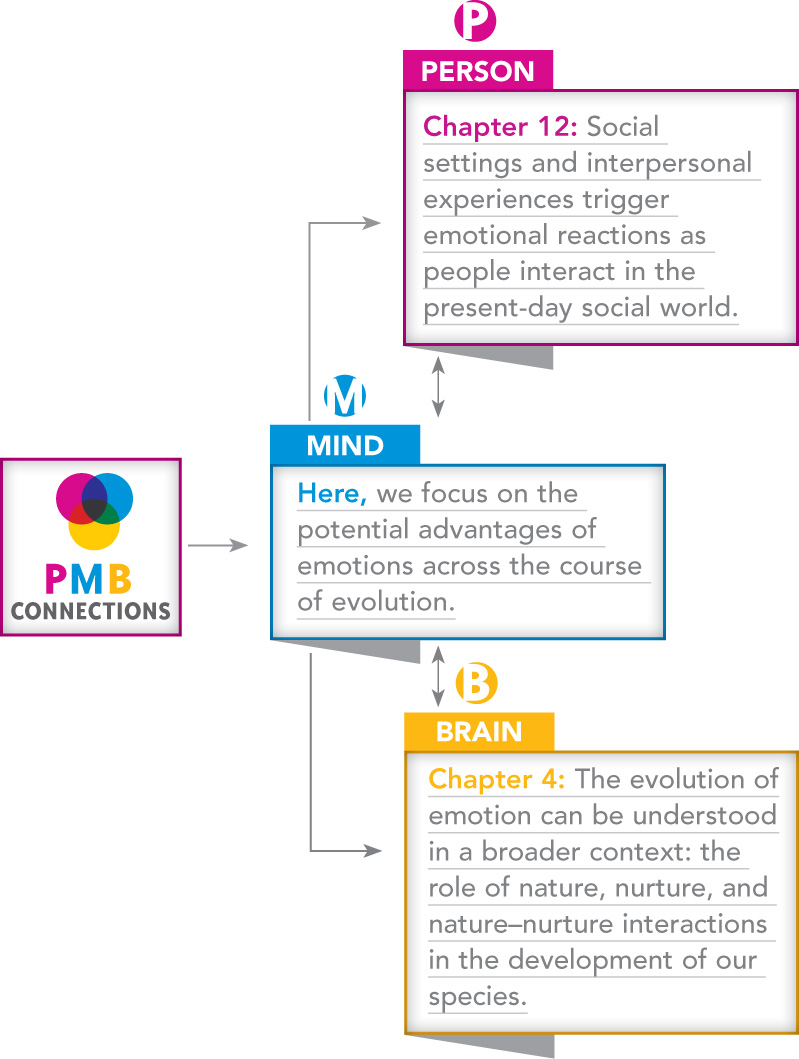

Ever since Darwin, scientists have answered this question by looking to our evolutionary past (Nesse & Ellsworth, 2009). Throughout human evolution, emotions must have been advantageous; they must have promoted survival. Let’s consider four psychological activities that have been important throughout human history and that are influenced by emotional states: decision making, motivation, communication, and moral judgment.

412

EMOTION AND DECISION MAKING. Suppose you have to make an important decision. What should be your frame of mind? Many suggest it’s best to decide while in a calm, cold, unemotional state. Entire philosophies have been built around this idea. In ancient Greece and Rome, Stoic philosophers promoted a calm, unemotional lifestyle because they thought emotions impair sound judgment (Solomon, 1993).

CONNECTING TO NATURE AND NURTURE IN THE EVOLUTIONARY PAST AND TO CONTEMPORARY SOCIAL INTERACTION

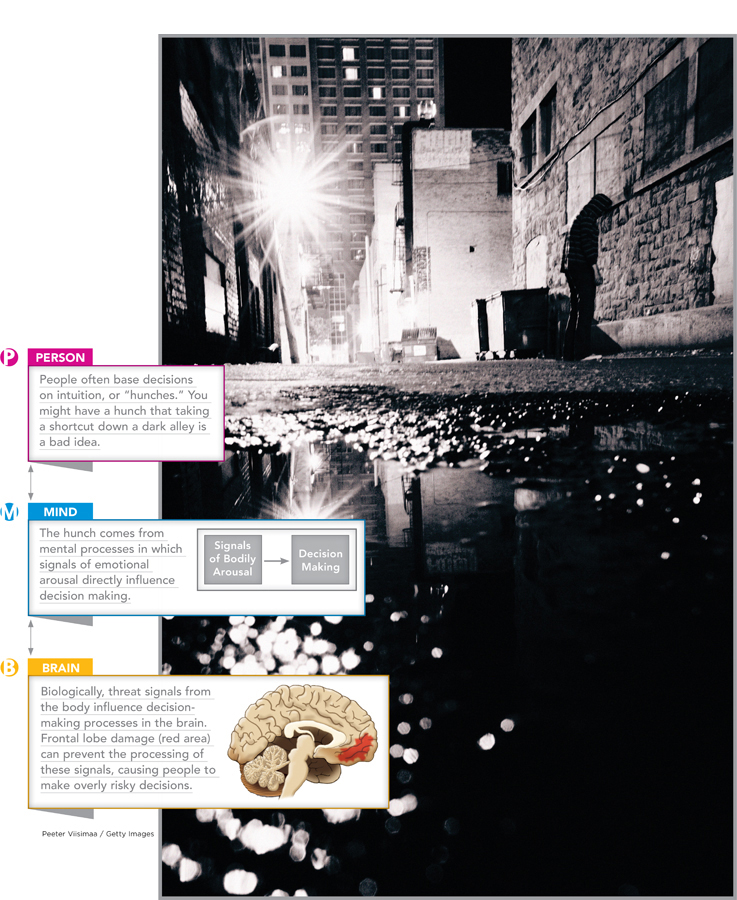

Contemporary research contradicts the Stoics. People often make good decisions when they “go with their gut,” that is, when they base decisions on feelings. Research employing the Iowa Gambling Task (Bechara et al., 2005) demonstrates this.

The Iowa Gambling Task is a method for studying the influence of emotions on decision making. Participants play a card game. On each of a long series of trials, they (1) pick a card from one of four decks and (2) win or lose money, depending on the card they picked. Cards from two of the decks turn out to yield consistent but modest winnings. Cards from the other two decks yield larger winnings on many trials but, on occasion, produce very large losses; in the long run, people lose money by picking cards from these decks. While people decide which card to choose, researchers record their nervous-

The Iowa Gambling Task yields a remarkable finding: Emotions benefit decision making (Bechara et al., 1994). To understand this result, one must distinguish among three types of experimental trials that occur during the task (Table 10.1).

Early trials: Initial card choices made at the beginning of the experiment

Middle trials: Card choices made after participants have experienced a limited number of successes and failures on the task

Late trials: Trials near the conclusion of the experiment, after participants have experienced a large number of trials, with success and failure, on the task

413

The research yields the following results. On early trials, participants are just guessing. They have not yet figured out the task; that is, they cannot say which decks are bad and which are good, and they do not have any intuitions about how best to play. During early trials, they are as likely to choose cards from the bad decks (those that produce occasional large losses) as the good ones (those that produce consistent modest winnings).

On late trials, participants have figured out the task. They can explain, in words, which decks are good and which are bad. They perform well, choosing cards from the good decks.

None of this is surprising. But here’s the key result (Bechara et al., 1997). On middle trials, participants cannot explain in words which decks are bad and which are good; they have not yet played long enough to possess explicit knowledge about which cards to choose. Yet they perform well, choosing cards primarily from the good decks!

How can they have made good decisions without being able to say which decks were good or bad? They relied on their feelings. On the middle trials, whenever participants reached for a card from the bad deck, they tended to experience high levels of physiological arousal; their body’s emotion systems sent a signal indicating that these decks were bad (Damasio, 1994). When they felt this signal, they avoided the bad decks and chose the good ones—

Have there been times when you should have gone with your gut but didn’t? Were your emotions perhaps telling you something?

Research on patients with brain damage provides additional evidence of how emotion benefits decision making (Damasio, 1994). The brain damage, which affected the brain’s frontal lobes, interfered with patients’ emotional life but not their thinking abilities. Cognitively, the patients were normal, with more than enough intelligence to understand the task. But emotionally, they differed from others; when playing the Iowa Gambling task, the brain-

These results suggest one evolutionary advantage for emotions. If people with normal emotional arousal make good decisions, and brain-

During middle trials of the Iowa Gambling Task, participants’ performance is unusual. They cannot explain which card decks are good and bad, yet they make good decisions anyway, choosing cards primarily from the good deck. Their emotional arousal guides their decision making.

| Iowa Gambling Task | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Early Trials |

Middle Trials |

Late Trials |

|

Cognition (Can participant explain which decks are good/bad?) |

No |

No |

Yes |

|

Emotion (Participant’s physiological arousal when choosing card) |

Low |

High |

High |

|

Decision Making (Does participant choose cards from the good decks?) |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

414

415

Over the course of evolution, emotional experience may have helped organisms survive by fostering quick, intuitive decisions that promoted survival. Much recent research confirms that emotions influence decision making, while also revealing additional brain systems that underpin the relation between feelings and decisions (Wu, Sacchet, & Knutson, 2012). This body of research provides a rich, multilevel understanding of how emotions influence decision making.

EMOTION AND MOTIVATION. Throughout most of human history, survival was a lot of work. People had to hunt and gather food, build shelters, protect themselves from predators, and, once agriculture developed, grow, harvest, and store crops. To do all this, they needed to acquire skills that would enable them to be good hunters and gatherers, builders, and farmers. Where did they get the motivation to learn difficult behaviors and then engage in them, day after day, year after year?

Part of the answer involves thoughts about the future. People understood that if they didn’t work today, there might not be enough food tomorrow. But, as you know from experience, sometimes thinking is not enough. People often think about future plans—

Emotions have motivational power (Lazarus, 1991). Anger motivates you to strike out at someone. Disgust motivates you to distance yourself from the disgusting stimulus. Even less intense emotions can motivate action. Consider the emotion of interest.

Interest is an emotion you experience when engaged in a task that, to you, is novel, complex, yet comprehensible (Silvia, 2008). If, for example, you are knowledgeable about modern art, an exhibit of new paintings is interesting; you are intrigued by its novelty and can comprehend its complexity. But if you do not follow modern art, the show might be incomprehensible and thus of no interest to you.

Interest increases motivation. People who experience the emotion of interest when working on a task tend to spend more time on it and need less time to learn its complexities (Sansone & Thoman, 2005). This suggests an evolutionary advantage for the emotion of interest. Throughout human evolution, people who felt interest in activities may have been better at learning skills necessary for survival.

Which of your current classes present material that is novel and complex, yet comprehensible?

Similarly, other emotions may have been beneficial throughout evolution. Fear motivates people to avoid situations that are threatening, and thus may have helped our evolutionary ancestors to survive by avoiding threats. Guilt motivates people to treat others well and to adhere to social rules (Baumeister, Stillwell, & Heatherton, 1994). This behavior, in turn, could benefit group survival.

EMOTION AND COMMUNICATION. A third function served by emotion is communication. Emotions communicate information. When people are emotionally aroused, you can tell from their looks; their emotional expressions convey information about their psychological state.

A key source of emotional information, as noted above, is the face. Facial expressions can reveal the specific emotion a person is experiencing. Look back at Figure 10.1. You immediately can recognize each emotional state. Every facial expression, in other words, communicates information about emotion.

Darwin (1872) noted two key facts about emotional facial expressions. First, the ability to communicate through facial expression can improve an organism’s chances of survival. Consider, for example, how facial expressions benefit infants. Although babies cannot communicate through language, they can communicate; their facial expressions indicate whether they are content or in need. Conversely, adults, through their facial expressions, can communicate with infants, who recognize smiling and frowning faces by 3 months of age (Barrera & Maurer, 1981). This two-

416

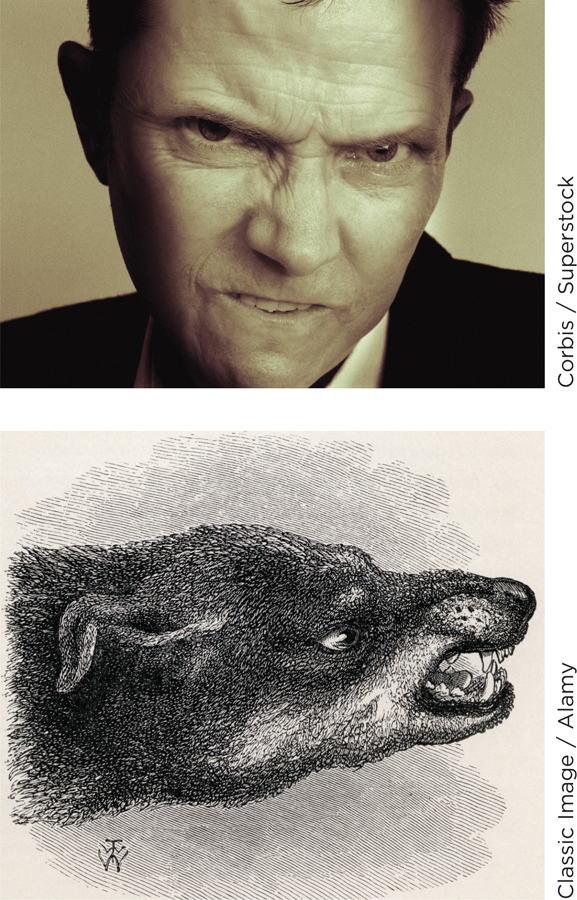

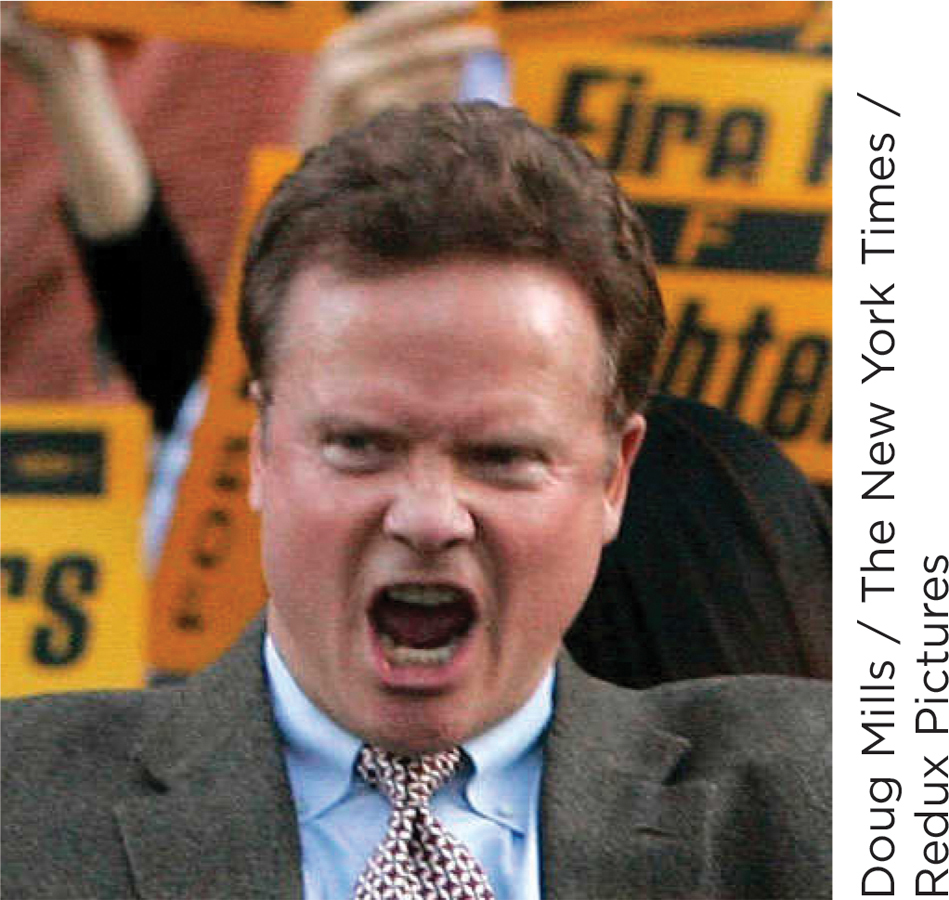

Second, Darwin noted that some human and animal facial expressions are similar. An angry man and an angry dog both lower their eyebrows and bare their teeth (see photos). This implies that the emotions evolved in mammals prior to the evolution of humans and that humans and animals possess essentially the same emotion-

The chief expressive actions, exhibited by man and by the lower animals, are…innate. The young and the old of widely different races, both with man and animals, express the same state of mind by the same movements.

—Darwin (1872, p. 191)

You’ve just seen that emotions (1) enable communication and (2) are a product of evolution. Combining these facts yields a fascinating implication: People around the world should be able to communicate with one another through facial expression. Why is that? Human biology is universal; people in all parts of the globe share the same basic biological structures and functions (arms, legs, torso, and head; digestion, respiration, etc.). If evolution gave rise to emotions and emotional expressions, then they should be universal, too. People in different cultures should display similar facial expressions when experiencing the same emotion, as well as recognize emotional expressions displayed by people from other cultures.

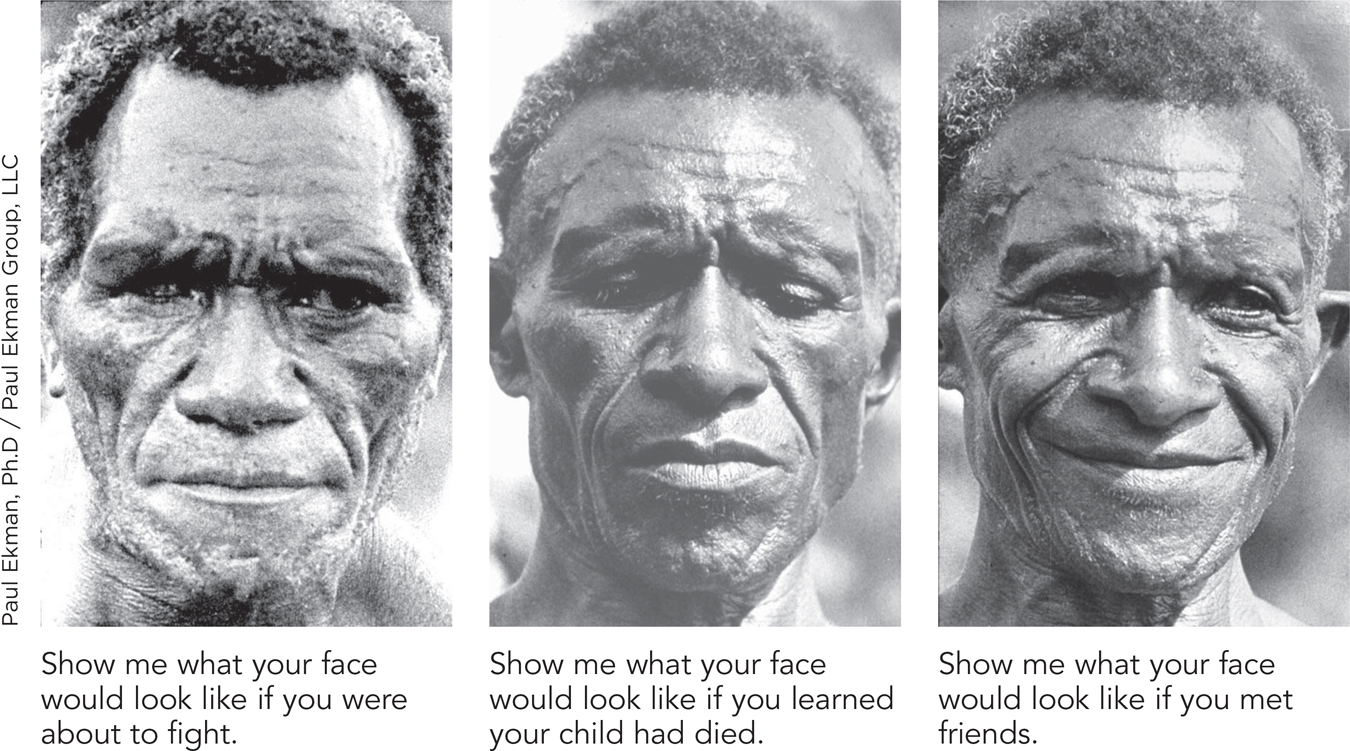

In classic research, Ekman and Friesen (1971) tested this idea among members of an isolated group: the Fore people of New Guinea. Individuals in this culture had minimal contact with the outside world; they interacted almost exclusively with members of their own culture and had never seen a movie or TV show. Thus, they could not have learned, though social experience, how Westerners display emotions on their faces. Ekman and Friesen showed Fore individuals photographs of people of Western culture posing facial expressions of happiness, sadness, anger, surprise, disgust, and fear. Could the Fore recognize these emotions?

417

If facial expressions are like words—

Biological research on the anatomy of facial muscles likewise suggests that facial expressions are universal. A specific set of muscles produces facial expressions of emotion. Anatomical studies show that there is little person-

THINK ABOUT IT

Ekman’s research suggests that a given facial expression is always associated with a given type of emotion. Is that always true? Or might emotional expressions differ from one situation to another? Consider the man shown in Figure 10.4a. He looks angry and hostile. But is that how he’s really feeling? See Figure 10.4b to find out.

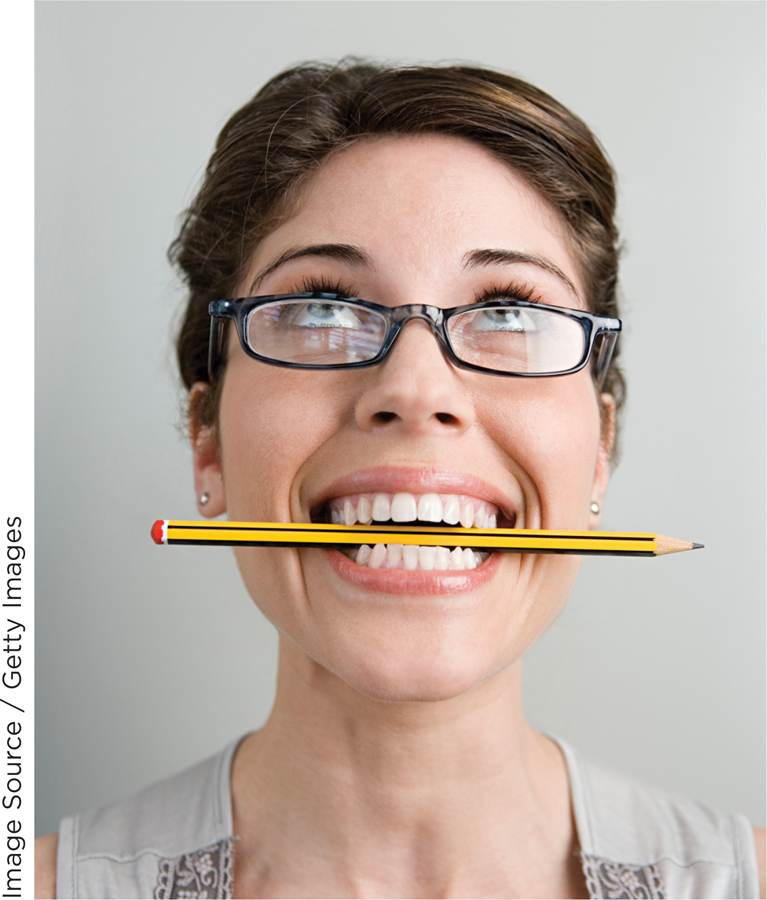

In addition to expressing your feelings, facial expressions can influence the emotion that you feel. Research findings support the facial feedback hypothesis, which is the prediction that biological feedback from facial muscles directly influences emotional experience. To test the hypothesis, experimenters ask participants to perform simple tasks that move their facial muscles into positions that correspond to positive or negative emotions. They then measure people’s emotional state. When participants are asked, for example, to hold a pencil in their teeth—

418

Other tests of the facial feedback hypothesis involve Botox, a cosmetic treatment that reduces wrinkles by lowering the activity of facial muscles. Two Botox-

Botox slows people’s understanding of written sentences containing emotional content (Havas et al., 2010). By limiting the facial muscle movement that occurs naturally as we read emotional content, Botox actually reduces the emotional feelings that can help people to rapidly understand emotion in text (Glenberg, 2010).

Botox reduces neural activity in regions of the brain that contribute to emotional experience (Hennenlotter et al., 2009). In both cases, the impact of Botox on emotion implies that facial muscles infl uence emotional experience.

Although biological factors contribute strongly to facial expressions, culture plays a role, too. The exact facial signals that people use to infer others’ emotional states vary across cultures. Evidence of this comes from a study using digitized photos in which facial features in areas around the eyes, mouth, and eyebrows were systematically manipulated (Jack, Caldara, & Schyns, 2012). Researchers asked both Western Caucasian and East Asian participants to view the photos and judge the emotion each displayed. Through a statistical analysis, they then identified the facial features to which participants paid greatest attention. These features differed across cultures. Western Caucasians concentrated on the eyebrows and mouth when making judgments about emotion. People in East Asia paid more attention to direction of gaze, that is, where the person in the photo was looking (down, up, left, or right). The exact reason for the cultural difference is not known, but it may reflect differences in the way people express, as opposed to hide, their feelings in different cultures (Jack et al., 2012). Whatever the exact cause, the results argue against the notion that evolved biological factors completely determine the “language” of emotional expression.

Facial expression is not the only way people communicate emotions. Another is nonverbal vocalizations, that is, sounds that do not involve words. In the United States, people cheer when celebrating, growl when angry, laugh when amused, and scream when afraid. Do people in other cultures make these same sounds while expressing these emotions? To find out, researchers (Sauter et al., 2010) obtained recordings of these various sounds (people cheering, growling, etc.) among members of two cultures: one European and one African—

419

The researchers read stories with a variety of emotional content to people in both cultures, played for them sounds of emotion recorded in the other culture (i.e., Namibians heard the sounds made by Europeans and vice versa), and asked participants to match sounds to emotions. The responses of participants from both cultures were highly accurate (Sauter et al., 2010). For example, despite having no contact with Westerners, Namibians could recognize what Europeans sound like when angry, sad, and fearful. The results suggest that emotional vocalizations, just like emotional facial expressions, are substantially based in evolved biology. They are not learned “from scratch,” but instead reflect an inherited system for communicating emotional states to others.

What emotional vocalizations do you use most frequently?

RESEARCH TOOLKIT

Facial Action Coding System (FACS)

To study emotions, you have to measure them. Researchers need a measurement tool to identify the emotion a person is feeling and how long it lasts. What tool will do the job?

One possible method is self-

Fortunately, it has one: the Facial Action Coding System (FACS; Cohn, Ambadar, & Ekman, 2007). FACS is a method for measuring emotions that does not rely on self-

As you learned from the main text of this chapter, different emotions are associated with different facial expressions. When a person starts to experience an emotion, there is a facial “action”: movement of one or more parts of the person’s face. By classifying, or coding, these actions, FACS provides a systematic method for measuring expressions of emotion.

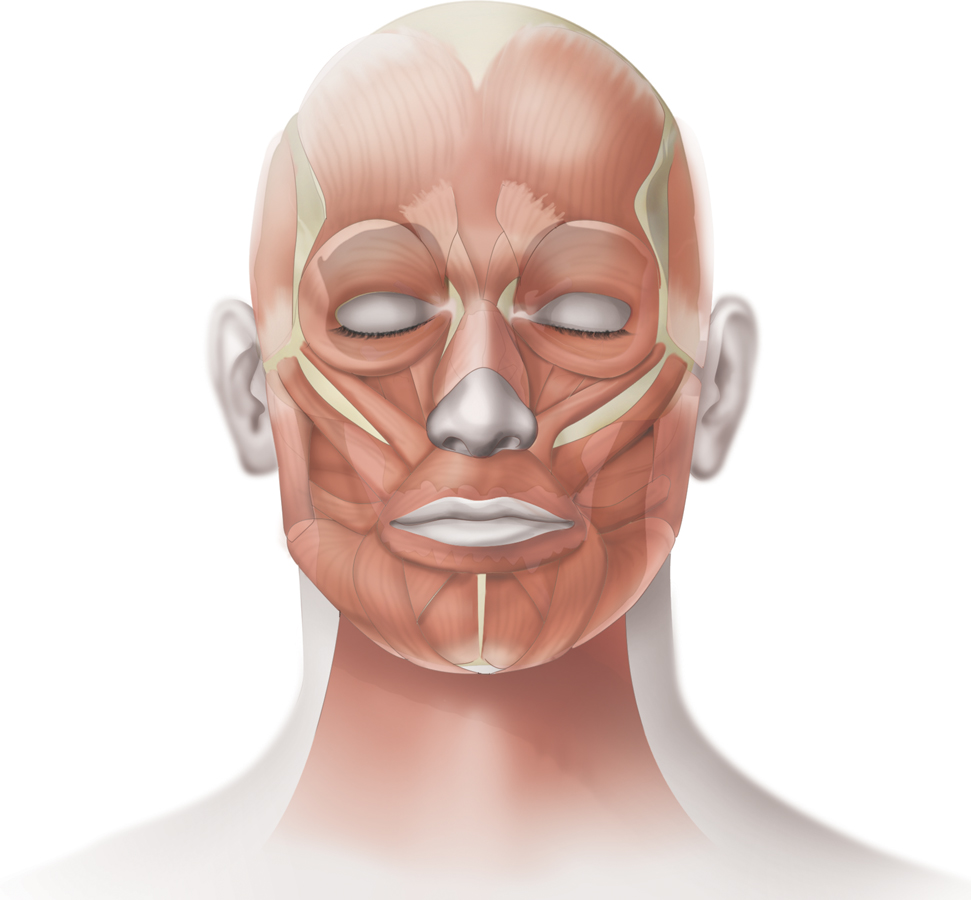

The FACS method is based on an analysis of facial anatomy. Facial expressions employ a specific set of muscles (Figure 10.5), and the FACS coding scheme classifies their movements. Specifically, FACS provides coding for 9 movements in the upper face (e.g., movements of eyebrows), 18 in the lower face (e.g., various mouth movements), and a set of additional movements of the head as a whole (e.g., tilting the head). To code these movements accurately, researchers film people’s faces using high-

420

FACS has opened the door to a number of discoveries about emotions and facial expressions. Here are some examples:

Embarrassment: There is a distinctive facial expression associated with feeling embarrassed (Keltner, 1995). Facial signs of embarrassment include a tight-

lipped smile, eyes directed downward, and head turned slightly away from another person. Genuine versus social smiles: Genuine smiles differ from fake, “social” smiles (Ekman, 1993). Both involve movement of facial muscles to form a smile. But during genuine smiles, unlike fake ones, people move muscles that produce wrinkles (“crow’s feet”) in skin near the corners of the eyes.

Micro-

expressions: Skilled law enforcement officials are able to catch liars by detecting “micro- expressions” of emotion, that is, extremely brief emotional expressions that can reveal the liar’s inner emotional state (Ekman, O’Sullivan, & Frank, 1999; Frank & Ekman, 1997). They are especially able to do so with the benefit of highspeed filming (Polikovsky, Kameda, & Ohta, 2010).

The FACS is a major advance in the measurement of emotion. Yet, as a measure of inner emotion state, it is imperfect. Factors other than inner feelings can influence facial expressions; for instance, the link between positive feelings and smiling is stronger when people are around others than when they are alone (Mauss & Robinson, 2009). FACS assessment thus may benefit from considering not only people’s emotion states, but also the social contexts in which they experience and express them.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 3

/puKSLcheFBCvIa/zUzuATP4EBkHagfGF6+UpynfIzXVzbaoa2qgtgCDiMHOQf5diu950E2J4I52ZdfnBiVSr6wL+DRiMJ+1a0nOtcwpbtj+eQz+3l5tZWVC5MCGTM4tsMsHlqUS2xDwBhV8zPZWkzr246YZYurxI7xoT3IeN5MSWOVQGycKlva0R1KZLKwUXAW7ksZEarKUgi8TKLSBa7kWnriANjr53LtZcSv4KL8t90CRWMLvk0QlwG3hVNcl27BLuW6zz/vhQK6M7WybAxe29UM7/k64OZlGUctEJiYl9/DoU3G9PudMb6J3olosItZs8or4aK6CGsm6nPF0tq04AjuikEr3sUkOTmdjOZr1DpzfHZIiYlUQ+3I=In sum, a wealth of research suggests that a third function served by emotion across the history of our species is communication of feelings and intentions. A fourth function concerns moral judgment.

EMOTION AND MORAL JUDGMENT. Moral judgments are decisions that involve fundamental questions of right and wrong. Compared with other judgments, moral judgments are ones in which you are certain that your belief is absolutely right and you cannot be convinced otherwise (Skitka, 2010). Suppose you hear in the news that someone in a supermarket line knocked a few other shoppers unconscious so he could check out more quickly. Is that OK? Of course not; it’s immoral, you’re sure of it, and could not be convinced otherwise.

How do people make moral judgments? Sometimes they rely on thinking—

421

Research by Jonathon Haidt (2001) shows how emotion contributes to moral judgment. Participants read about hypothetical behaviors that (1) cause no harm to anyone, yet (2) feel morally wrong (e.g., eating a dead pet dog, or a brother and sister having sex). Participants were certain these behaviors are wrong. Yet they couldn’t say why. Haidt found that, when trying to explain their judgments in such situations, people are “morally dumbfounded…. [They] stutter, laugh, and express surprise at their inability to find supporting reasons” (Haidt, 2001, p. 817). These moral judgments are explained by emotional reactions; people experience the emotion of disgust when thinking about such behaviors and thus judge them to be immoral.

What is a behavior you think is morally wrong, even if you can’t come up with any specific legal reason why it is wrong?

TRY THIS!

The experience of moral dumbfounding should be familiar to you; it is the experience you likely had when completing this chapter’s Try This! activity. The second Try This! research task you worked on was used in the brain research on emotion and moral judgment that we will review now.

Brain research confirms that emotions contribute to moral judgment. In one study, brain images were taken as participants made judgments about different behaviors, some of which violated moral rules (Greene et al., 2001). When people were making moral judgments, regions of the brain involved in emotional experience were particularly active.

422

Again, the findings suggest that emotion was beneficial evolutionarily. Consider the case of sexual relations among siblings. During human evolution, such relations would have been very bad for survival; inbreeding increases the chances of birth defects, among other survival risks. The emotional reaction of disgust prevents the behavior and thus enhances survival of the species (Hauser, 2006).

So far in this chapter, we’ve discussed universals. All people, in all cultures, experience emotions that influence their decision making, motivation, communication, and moral judgment. But universals are not the whole story of emotion. When it comes to emotional life, people can differ.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 4

xAln1k1Ouzn0SlccsMSgqgjhvWdOd3aHmlQJC23cRs+nmvHKfa4nzjsCrMfGzlWjoo2SXAWvNGJ6RyYYZxWC6l2QM2isykBZISdC08VY5TI3jdppDQFfP4I2v10f4I0y/yERS3Hqf0P6Sl8lkTXlEG3WhBGEA+gBHEKheG5N5gedGXxtxadMcYSjQ5/9jMfPcoW+4CniqmNYdt746IbHfdBsuah8V9TTQUpICZfQLSKCnFVxL2xxOX80cbGp1L3AaaE3p2WZkG9iSzFuC4U36GdlWpzMwoiM5XllzR23am5RP8nNXsZP7uf2WIbxCuOw0CCKp0lIWg7agwBDQz8bgta5oJNh0Q6uDh2xqVo6pMSDhdYuPspC02nIRR+h5fkEWfmYna5HxtsyQyHM2l+CnfF69F7SazDTT1hqsB5UW4Y0HjEIjwlLvjwm3TfLsmyx3QpKZqjB/Lt6ohL3yIa6KPSZM5O4VfuQ2yloyj1v1CJR1TDGTzfI5ut8ulCsaLccibJuqZOrLS+kFiEkFVz5em3D81n2Ka/mDL11RfuHgHkvEqi7dB98IPB7LaYjNNe+Rghl5fcApUyAiqhVdnHjgkDhY+C7yQARJcVZTe8IcIozw1atNoUgZ7BFuMM6bHOubEZBqaTWUwCoWN8XzSmLYIRzZf81/+jWI9FT5m94KDOHhs6V6EGOeDXwdbSbUReTX2xypFaVXXp6RwtmiC1HKOYPkTMOAIjiibd/Mlp2ajx1XKF4Ym+enGylORpJpw9h9r9E6yc61/91dRHfHf8vHcIJYe26H5ZfLEXYz/p4iyvbjSs/0yOEppegpT6N1u4eoELI3l2StyfS0AxX6xgaCOXx1EHL6CsAt5Q14qVO2uLkxdYy48111awgQBdGqWK1uhslBaFskxPjxgJ4H97kgm2VriBTR9YiSLKrvVjesyZcLjBm8Wypumd4KgCajS9vzKAOFzQk6h2uv00qEWvobj2OFbtAznsjPmD2e8+5mvEsF0Ycu84/FEwq713KHcR2etFgF0l4lY+yOxeAn6l0PrixjhaZWyEVIo0cxHPo2hai1SaWjg2QsS6856a9X2cadVQHtOU1JCZ6C/PlWhy Do People Have Different Emotional Reactions to the Same Event?

Preview Questions

Question

How does our thinking affect our emotions?

How does our thinking affect our emotions?

What kinds of thoughts influence emotional experience?

What kinds of thoughts influence emotional experience?

People confronting the same event can experience markedly different emotions. For instance, if two students get a D on a chemistry exam, one might be sad but the other anxious. If you tell a joke about lawyers to two people, one might be amused but the other angry. Why do people’s emotions differ?

THE PERSONAL MEANING OF EVENTS. Environmental events, by themselves, do not produce emotions. Emotions result from the meaning that people give to events. The personal significance of an event—

Individual differences in emotional experience therefore reflect the power of thinking. Thoughts shape emotional experience. When people’s thoughts vary, emotional experiences vary, too (Lazarus, 1991; Scherer, Schorr, & Johnstone, 2001).

Thoughts so powerfully shape emotions that people can have a wide range of emotional reactions while merely sitting around by themselves. Even if nothing changes in the outer environment, changes within the mind can alter our emotional state (Nowak & Vallacher, 1998). Novelists capture this circumstance vividly. Consider the emotional life of a character created by Russian writer Leo Tolstoy. He begins in happy reverie, dreaming of the joys of married life as he sits in a hotel room just prior to his wedding. But then, look what happens:

423

Happiness is only in loving and wishing her wishes, thinking her thoughts…that’s happiness.

“But do I know her ideas, her wishes, her feelings?” some voice suddenly whispered to him. The smile died away from his face, and he grew thoughtful. And suddenly a strange feeling came upon him. There came over him a dread and doubt—

He jumped up quickly…with despair in his heart and bitter anger against all men, against himself, against her.

—Tolstoy (Anna Karenina, 1886, p. 451)

His shifting thoughts about a highly meaningful event—

APPRAISING EVENTS. The examples above have something in common. The thoughts that produce emotions are ideas about the relation between an event (the grade, the joke, a fiancée’s feelings) and the self. “My parents will kill me”; “My mom’s a lawyer”; “What if she does not love me?”

People react emotionally to events that they see as relevant to their own well-

Psychologists call these judgments appraisals. Appraisals are evaluations of the personal significance of ongoing and upcoming events (Ellsworth & Scherer, 2003; Lazarus, 1991; Moors, 2007).

APPRAISAL THEORIES OF EMOTION. According to appraisal theories of emotion, people continuously monitor the relation between themselves and the world around them. They pay attention to, and try to determine the meaning of, daily events from the large (a long, serious discussion) to the small (a quick, ambiguous glance). Appraisal theories of emotion explain that this process of making sense of events—

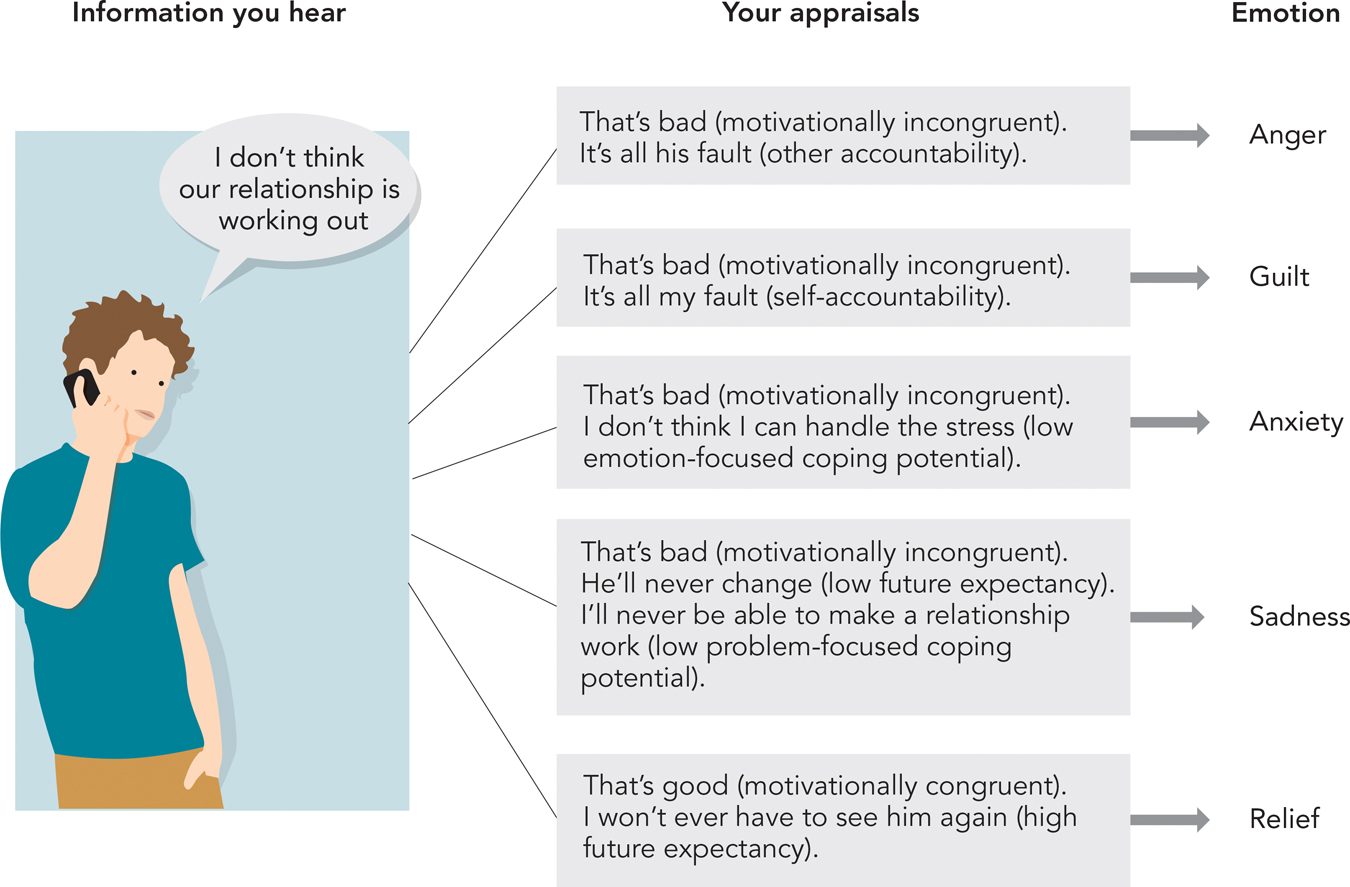

The psychologist Richard Lazarus identified a small number of appraisals that can generate a wide variety of emotional experiences (Lazarus, 1991; Smith & Lazarus, 1990). In his appraisal theory of emotion, key appraisals include the following:

Motivational significance: Is the event relevant to my concerns and goals?

Motivational congruence: Does it facilitate my goals or hinder them?

Accountability: Who is to blame (or who deserves credit) for an event?

Future expectancy: Can things change (e.g., for the better)?

424

Problem-

focused coping potential: Can I myself bring about change that solves a problem? Emotion-

focused coping potential: Can I adjust, psychologically, to the event?

A simple example shows how these appraisals shape your emotions. Suppose your relationship partner tells you it’s “not working out” (Figure 10.6). You could experience any of a number of different emotions when hearing the news. The exact emotion you experience will be determined by your appraisals—

There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.

—William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act II, scene ii

Thus, there is a lot of thinking behind emotions. Without thoughts like “I’m to blame” or “Things might improve,” you wouldn’t experience emotions such as guilt or hope.

Despite all this thinking, emotions happen quickly (Barrett, Ochsner, & Gross, 2007). You can experience complex emotional reactions “in the blink of an eye” because your thinking is fast, too; people appraise events automatically, in a fraction of a second (Moors & De Houwer, 2001). If a boyfriend calls to say a relationship isn’t working, multiple thoughts—

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 5

MaIwgBotZf1ApROgwGd/J9ABTuwdHs5tCuaKJ7eRmpdi2vNEQ49FGVy2EUIFAL2e6efu0TBiUWrn/QeFRW6Zw7S+8N3deDNWyNa8fHiDtkHAuY3TXGrvYyvhHnSnf51ZEPaMiQaLi+0Po3Zyeq09vgjPaLDBJ4XXh6i2TsG+yGIHh1KmZQWDQaXPGtsy8xLvdvi83NKhJW/Nxc6fRJMqBj29GKAtY/nOB6RuSgRn7CvchM8J4EuQpDrAL/x8yXI3rg765qTunpbQisULk0WMzTijIkuLs6WyeygJOHGNpm3lSOBPlqwEvULRQsHXOijBn5YAHEcFWn+w7NJbzDIobnfoFccCc09GScJ6jktyftggML/cVzslEfQ+hch0Trsv99j5jhfYr7phiisphO2GEkIl4equ2F/6Xv/Z12qbqtXAebp3lmvJiBVTeblFr87p2tK3T0MBZ3hQQdna+aPsa6ENj97R5VuEPb1s6xA9jYtU3flyWCuDRUVm94LU82VUpS11SJ2hzjiOZxU7DoxrhmKT+ac=425

CULTURAL OPPORTUNITIES

Culturally Specific Emotion

Do people the world over experience the same emotions? Or might people in one culture experience emotions that don’t even exist in another?

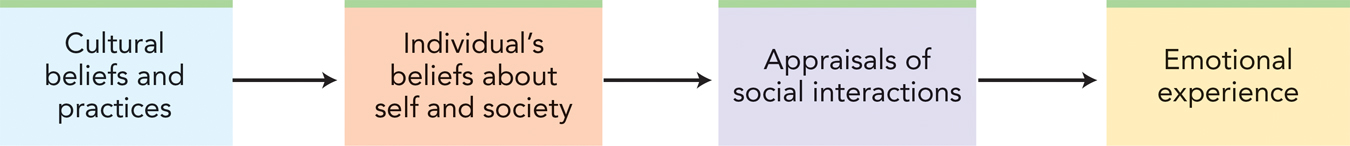

Appraisal theories of emotion suggest one answer. As you learned from the main text, appraisal theories explain that the emotions you experience are determined by the meaning you attach to events. Your appraisals—

Research in cultural psychology reveals that different cultures teach people different lessons about individual rights and obligations (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Therefore, people from different cultures may differ in the appraisals they make and the emotions they experience (Figure 10.7). Appraisal theories of emotion, then, suggest that emotional experience may vary across cultures. People might experience emotions that are unique to their cultural setting.

Let’s consider an example from the Hindu culture of northern India (Shweder, 2003; also see Parish, 1991). This culture is “collectivistic” (see Chapter 12). Compared to the culture of the United States, which emphasizes people’s individual rights (and thus is “individualistic”), Hindu culture emphasizes the collective: the family, community, and society as a whole. Individuals who grow up in this culture repeatedly learn about their social obligations. They are taught lessons about how they should act in order to fulfill their duties to society.

Within this particular collectivistic culture, the social obligations of men and women differ. Cultural norms dictate that women should act in a modest, deferential manner. They are expected to be quiet, not to make a show of themselves, and to respect the wishes of others (Shweder, 2003). Thus, individual women who grow up in this Hindu culture believe that it is their personal obligation to uphold this cultural norm.

How does this affect emotions? These culturally grounded beliefs produce an emotion that is relatively unknown in the United States: lajja. Lajja is an emotion that people feel when they are “behaving in a civilized manner and in such a way that the social order and its norms are upheld” (Shweder, 2003, p. 160). Women feel lajja when they are acting in a shy, respectful manner toward others. In other words, rather than feeling bad because they seem shy and are not “standing out from the crowd,” they feel good that their actions are consistent with their obligations to others.

Researchers who study this culture argue that lajja does not correspond directly to any emotion experienced in Western culture (Shweder, 2003). Lajja does not, for example, correspond to “pride.” People feel proud when their personal achievements are outstanding and superior to others. But lajja does not involve any sense of superiority; just the opposite, it is a sense of “fitting in” to a social organization in which others are superior.

If you, the reader, are not from India, you may be thinking that you can’t tell—

426

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 6

The following statements are incorrect. Explain why.

- J9mQmR1rzuh2BebBTs59esm913dAeQq2zz5q9uIobr5wyGVw4LX5AvPebOO+WSGZISaJz2iSvdrnCOUc32hikwFT4EwGOqaQzj0UaJWsy91wDQv6xTurVRFxzl1RP1VHIoP2J0+LT8X0XmRcGbj/MfVxobnEL7TGupgZ1CUyBHWPkthl1ZEeJv1C7Mb4KEC9bvJoKioU2nw=

- 9GcfvDLHeqqahnKtPcJztL1csK6Q2YSUET+hlvvnpMWnYMVml0V0bxOis0ie60nOIYj+WdQpIg/MiJZWrfF4bNB5vhSAOACGnaUKn3wBF8+sLmsL63EQS5fz5IyTmJ3ZIoULhw0U2dSSWUl9+XWN7iB/dO8iEUf5s/scgbI6d6ekM42n

a. This statement is incorrect because lajja cannot be said to be universal. It is not experienced by individuals in individualistic cultures such as in the United States.

b. This statement is incorrect because appraisal theories of emotion are particularly well suited to explaining cultural differences in emotional experience. These theories suggest that emotions are shaped by people’s beliefs—beliefs that are shaped, in part, by culture.

Can You Control or Predict Your Emotions?

Preview Questions

Question

What can we do to control our emotions? What shouldn’t we do?

What can we do to control our emotions? What shouldn’t we do?

How well can we predict the degree of our happiness if we win a lot of money?

How well can we predict the degree of our happiness if we win a lot of money?

Emotions sometimes seem unmanageable. Tragedies cause grief that can seem over-

CONTROLLING EMOTION BY CHANGING APPRAISALS. Appraisal theories suggest that they can. Because appraisals—

What upcoming event do you have planned? What are your anticipatory appraisals about it?

One way to change your thinking is to alter anticipatory appraisals, which are thoughts that people have prior to the occurrence of an event. If, before a trip to the dentist, you tell yourself, “This visit is going to be terrible!” then your thought is an anticipatory appraisal.

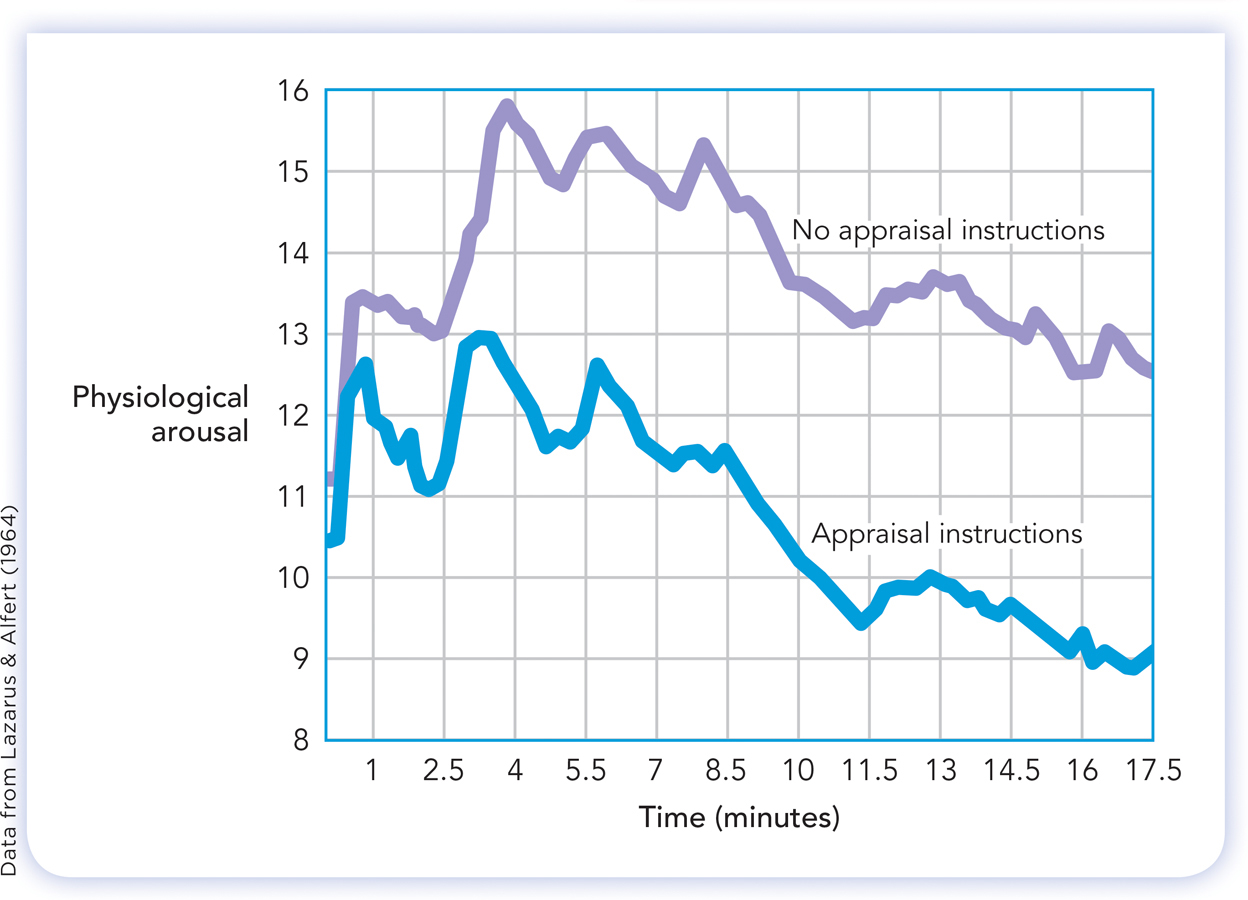

In one experiment on anticipatory appraisals, researchers (Lazarus & Alfert, 1964) manipulated appraisals prior to a film depicting a potentially emotionally arousing event: a ritual surgical procedure conducted on boys in a non-

Through anticipatory appraisals, people also can gain control over impulsive emotions, specifically, impulsive desires to engage in a behavior that they are supposed to avoid. In research on delay of gratification (Chapter 13), children are asked not to eat a food treat that’s set before them, such as a marshmallow. Most kids can’t avoid it; they eat the treat even when instructed not to. However, children who are taught anticipatory appraisals—

427

SUPPRESSING SIGNS OF EMOTION. Sometimes it’s too late for anticipatory appraisals. You’re already emotional: angry, sad, fearful, disgusted. What can you do if you want to hide these emotions from others—

If you’re already emotionally aroused and don’t want it to show, you need to suppress your emotion. Emotion suppression is any conscious, intentional effort to prevent yourself from showing any visible sign of emotional arousal (Gross, 1998). If you are upset but try not to mention your feelings to others or let them show on your face, then you are engaged in emotion suppression.

A primary question about emotion suppression is its effects: Does suppressing an emotion reduce a person’s emotional arousal? Or, does trying to appear calm “backfire,” intensifying the emotional state instead? To find out, a researcher gave different instructions to three groups of participants prior to their viewing an emotionally stressful film (it depicted the medical amputation of a limb). In one condition, participants received anticipatory appraisal instructions similar to those in research discussed above; they were asked to appraise the film in a scientific manner, remaining emotionally detached while focusing on technical details of the surgery. In a second condition, participants received thought-

The two strategies for controlling emotion—

Other research links emotion suppression to a behavior many of us try to avoid: overeating (Butler, Young, & Randall, 2010). Every day for a week, people in heterosexual relationships indicated whether they (1) kept their emotions to themselves, rather than revealing them to their partner, and (2) ate more, less, or the same as usual amount that day. Among women who were overweight, but not among those who were underweight, thought suppression predicted overeating; on days when they suppressed their emotions, overweight women ate more than usual. Suppressing signs of emotion may have increased women’s negative emotional experience and prompted them to eat more as a way of coping with their negative feelings.

Have your efforts to suppress an emotion ever had these kinds of ironic effects?

428

PREDICTING YOUR EMOTIONS. Controlling emotions, as you’ve just seen, is difficult. Once an emotion starts up, efforts to suppress it can backfire. Let’s now consider something that seems like it should be easier: not controlling, but merely predicting your own emotional state.

How do you predict you would feel if you lost weight, started a new relationship, or won a lot of money? Or if you gained weight, experienced a breakup, or lost a lot of money? People usually predict that such events will have a big impact on their emotional life—

In one study (Wilson et al., 2000; Study 3), psychologists asked college football fans how happy they would be in the days following a big game if their team won. For each of a few days following the game (which the team did, in fact, win), these same participants completed a survey indicating how happy they actually were feeling. Fans overestimated the emotional impact of the win. The good news of the team’s victory had less strong and less long-

Overestimation is common. When predicting the effects of events—

These findings seem disheartening, implying that you can’t do much to change your emotions. You might predict that you’ll be happier if you break up with your current dating partner, transfer to a new school, or get a higher-

429

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 7

One way we can control our emotions is to alter anticipatory JYwW7h1RquHvysidOTtgrA==, the thoughts we have before an event occurs. This strategy is more effective than 4//tAYJL1WqxfnMHukTfuA==, which, ironically, can increase emotional arousal. Interestingly, people tend to Oqg2UtFKt7WNFnhS estimate the impact that life events will have on their emotions.

THIS JUST IN

Making Yourself Happier

Can you make yourself happier? Many psychologists had thought the answer was no. They reached this conclusion primarily due to results from studies of twins.

Identical twins’ reports of how happy they are with their lives are often quite similar; if one twin is happy (or unhappy), the other tends to be happy (or unhappy), too. Identical twins are more similar in their level of happiness than are nonidentical siblings, including fraternal twins—

But eventually more data arrived, and conclusions changed. A remarkably largescale study has shown that levels of happiness can, in fact, change, despite the influence of genetics (Headey, Muffels, & Wagner, 2010). Researchers in Germany studied more than 60,000 people, ranging from young adults in their 20s to older adults in their 60s. They studied them annually across a substantial time period, 1984 to 2008. The key measure was happiness, or overall satisfaction, with one’s life, measured on an 11-

This exceptionally large set of data produced two keys facts contradicting the view that happiness is determined entirely by genetics:

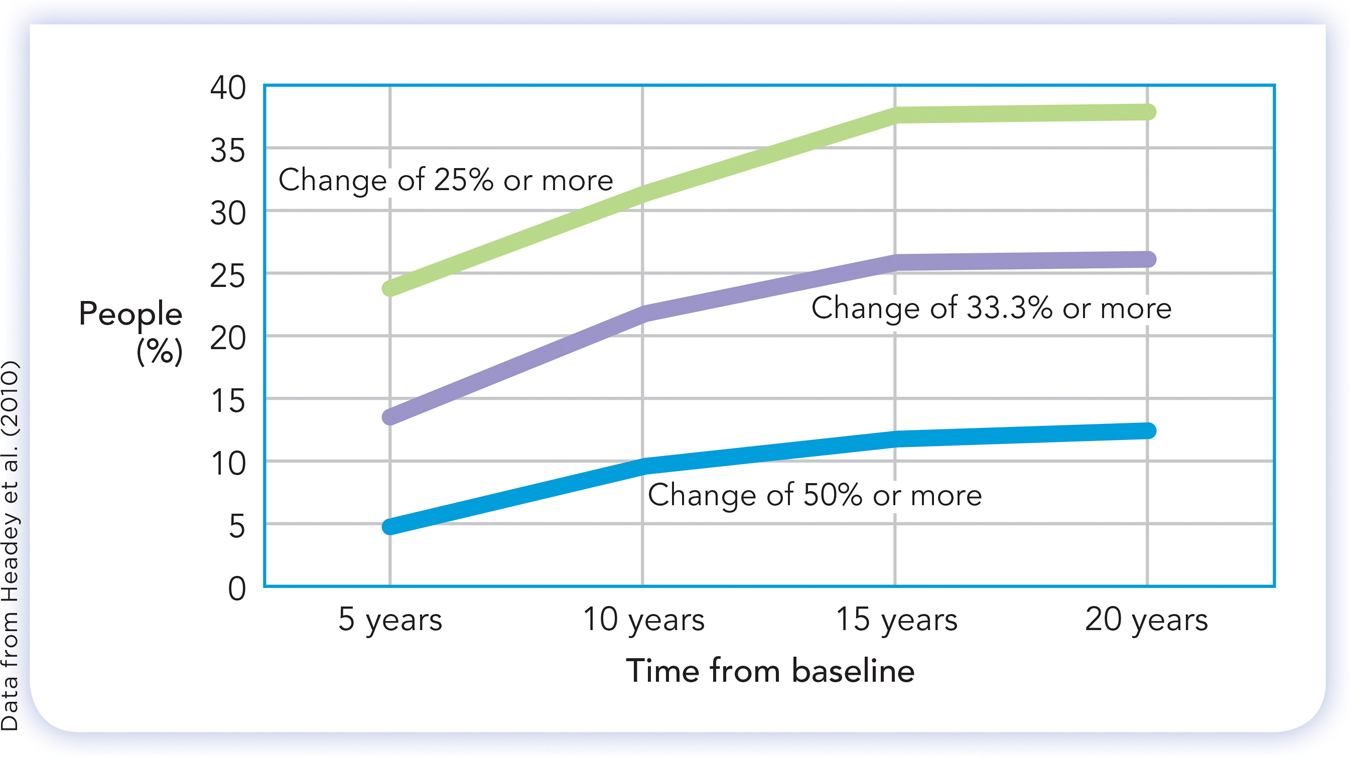

Change across time: Many people’s level of happiness with their lives changed substantially during the course of the study. Between 1989 and 2004, a large number of people (38.1% of the overall sample) had experienced substantial changes in their level of life satisfaction (Figure 10.10). The idea that genetic factors produce a stable, life-

long level of happiness was blatantly contradicted. 430

Social factors promote happiness: A variety of life changes were found to promote happiness (Headey et al., 2010). One was the setting of goals for altruistic behavior, that is, activities that help others rather than merely benefiting oneself. People who committed themselves to altruistic life goals were found to experience higher levels of happiness with their lives; people whose primary goal was to acquire more material goods, by contrast, became less happy. A second life change affecting happiness was exercise. People who exercised frequently reported higher satisfaction with life.

So, there’s some good news for those of you looking to make your life even happier.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 8

Which of the following statements are true about happiness?

- m3q67Q9wst8rMZoQ45JNVQrv551YunwCrK4li0BLO9Owl6usmpH201PORGbTu+IldprQsqpWzeAGBpk0wPtRamtjLxSpwfDlwSnl+RY6t8Gd525HzDDfTRHTh3rHs4kk/ZiBNsmYsBGJfTZtAb4jIA==

- PK5aOBuUhydPqQbH5arTLVtpQkVLr4mNUVF6ZF8bscYQHp+3mIHacMGHUKVHqzX193IkiNFDxZ/cA0fYDRl5jcZZOh/VGdfY3OZ60R05oOnIOoSSc36m3NGuw39FJYZAESiUmFXCB6vsdWsPJ/fRaErml5CyHtnd95JtfzGuIUNd+FKT+11bqp84xCp8R4fYsV9uqE5W7Lf++ugiwT7hFAjZYnq1KTbHc7nLqHndeCULYbKHPlP4bg==

- lAWkK603UMXeAT8jf+PVIzP5qGsnqW/wMntQ2di7sEjXWEIZIHn6HvdNX/wBX6hgpLyE7ZKtm6bTAvSmAjln/ArvaadtJavTmDWPn9albjrcm+DpDDVK9GE5Ein9y2xItD/6/2Fh0yPsFqOeaHTif73YI6Y=

- E2MkZ7Xbr5SPxaj7vDjuw/10nNQNZBNkMHHNhObAN6zu1jjGCAlaFFqJbIpV7+3MsBwncA2G/F8PQEd4+tB1kV6uv0zDwRCACU1zulzNXPYXd/KCYedreYO0YEHQJQ1E7+Ftx9xymgnjkt11RT3nYoW/Ol7+dfZeXK9ZzcKC5gXktMze

- o75JXj+wOzxvcgHeH4ewAUOqlsVcey8k4Wp4sdRojuQyGgyGB6Ehg7vEMO3dEmcRsFHrYQoZo1iMTx4zHg2mblZStFQVGo69SQoQ6Wq4kjjFPIV5CImLoep3ce0=