10.3 Mood

How are you feeling right now? Decide which of the following words describes your current feelings. Are you feeling:

|

Relaxed? |

Calm? |

|

Gloomy? |

Jittery? |

|

Sleepy? |

Depressed? |

|

Excited? |

Peppy? |

|

Tense? |

Contented? |

Energetic? |

Sluggish? |

These words describe different aspects of mood (Russell, 2003; Thayer, 1996). Mood is your feeling state; the term refers to the feelings—

Sometimes you barely notice your mood; it’s in the “background” of your mental life, unnoticed until someone asks, “How are you feeling?” Sometimes, though, your mood dominates your consciousness. If you’re in a depressed mood, it can be hard to stop ruminating about how bad you’re feeling.

The Structure of Mood

Preview Question

Question

What does it mean to say that we can describe any mood with two simple structures: valence and arousal?

What does it mean to say that we can describe any mood with two simple structures: valence and arousal?

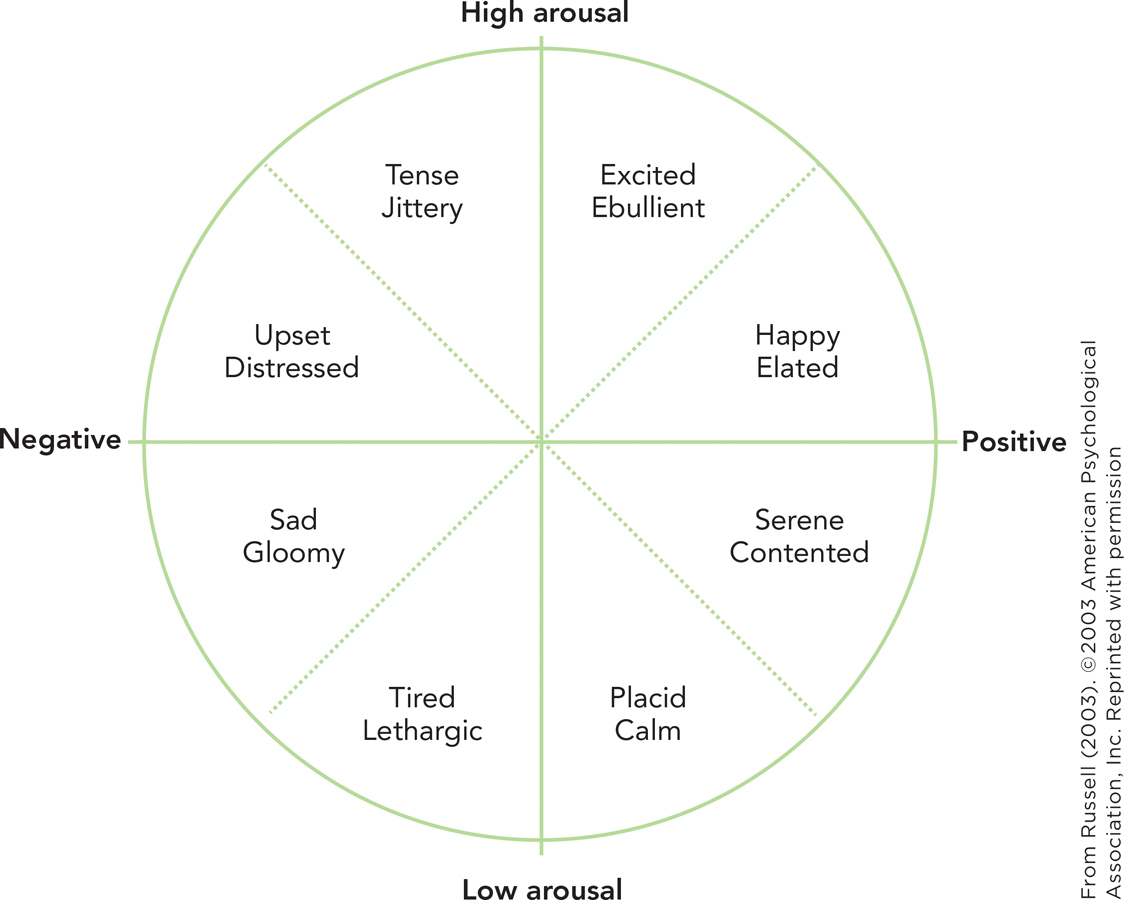

Look back for a moment at the list of mood-

Similarities: Some of the mood states described by the words are similar. “Tense” and “excited” are an example; the feeling of your body when you’re tense and when you’re excited is similar. Likewise, “gloomy” and “sluggish” are similar; if you’re feeling gloomy, it’s likely that you’re also feeling sluggish.

Opposites: Some of the mood states seem like opposites of the other. “Relaxed” and “tense” are an example. As you feel more tense, you simultaneously feel less relaxed; thus, they’re opposites. The same is true for “peppy” and “sluggish.”

MOOD DIMENSIONS. The similarities and opposites have an important implication. They suggest that the 12 mood terms in the list above may not refer to a dozen distinct, unrelated psychological states. Rather, there may be some underlying dimensions of mood. Dimensions of mood (or mood dimensions) are universal variations in feeling states, that is, variations that can describe the mood of any and all people.

An analogy will make the idea of mood dimensions clear. Instead of psychological mood, consider six terms we can use to describe the physical body: “skinny,” “chubby,” “thin,” “plump,” “emaciated,” and “rotund.” Although these six terms are separate words, they clearly do not refer to six separate, distinct physical qualities. Rather, they refer to variations in one underlying dimension: weight.

Similarly, although a large number of words can refer to mood, there may be a small number of basic mood dimensions. Mood terms that are opposites—

In the psychology of mood, the complete set of dimensions required to describe variations in mood experiences is called the structure of mood.

IDENTIFYING THE STRUCTURE OF MOOD. To identify the structure of mood, researchers rely on statistical tools. They statistically analyze survey responses in which people describe their moods on simple ratings scales. Research findings converge on a simple conclusion: There are two dimensions of mood (Russell, 2003; Watson & Tellegen, 1985). Although not all psychologists agree on the best labels for these dimensions, a popular approach identifies the dimensions arousal and valence.

Arousal refers to the level of activation of the body and brain during the mood state. It ranges from low (“calm,” “sluggish”) to high (“peppy,” “tense”).

Valence refers to the positivity or negativity of the mood, that is, the degree to which it is a “good” (e.g., contented) or “bad” (e.g., depressed) mood.

Psychologists combine these two dimensions to obtain a structure that can describe the spectrum of moods people experience (Figure 10.11). The structure functions like a map. No matter where you are on Earth, your location can be identified on a map defined by lines of longitude and latitude. No matter what your mood at any given time, it can be located somewhere in the “mood map,” defined by lines of valence and arousal (Russell, 2003).

432

Where are you currently located on the “mood map”?

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 9

lfNKVTcA9fG6LWPP2vnvsRNGBuN+t8h6Wxxa8rMFLSLhxazy1kP7jaPyKYbmn3AbjW1zCyp9k/YOoxfezuUNkSIAKHqJId3rdRBJJd+3AcqxrVbuJVY4l6xBJCDs8NRgHbXu7+0TLHP8ms9nNOcj0YaaFTjD/1tO6RiYuAbWtEQZmwUw9d4K6rJrSBO2SMoZLIlqqWNYm1uLnkkB8d6AQGYbzMXrEGlzZAJkFZDKYg0H+yE8Xt42rxLoTQeTGeVJNl86+t6l5Bazt+9sMjqiZoLZWwR9mHNxABFI1xYo1ZtCTVQB1rD2w8CcnnTSH6Xck78c1D4Kyk+AR6Y+ca2lYIGKA5A8lZIXuJZL2Fp7LTyvXhFWRYvm/ZSWjQNPkzzwd8AUNcM5Lqy+oxFM5x/1uUAPndSCENBjeFeSziO9y4EWdvPp32nV98xe/Hu6yHxA4P+ev31oo//2Y6TUgl7+BcGOEdsyQfuA6iaOM9fkx35U7352oj4XKi/BfW+ZdLElkfXxRkuq1BY=Improving Your Mood

Preview Question

Question

What activities have been demonstrated to improve mood?

What activities have been demonstrated to improve mood?

Just as a map describes your location but doesn’t tell you how to get somewhere new, the two-

THINK ABOUT IT

The two-

Many factors affect your mood. Some are life stresses—

433

PHYSICAL ACTIVITIES. One such activity is exercise (Thayer, 1996). Regular exercise can improve mood. Evidence of this comes from experimental studies that randomly assign people to experimental conditions in which they do or do not exercise regularly (Blumenthal et al., 1999). In a study of adults suffering from chronically depressed mood, one group of participants took 45-

The change in mood that resulted from exercise primarily was a shift along one of the two dimensions of the two-

In yoga, practitioners learn physical poses that build bodily strength and flexibility, while simultaneously focusing one’s attention in a calm and concentrated manner. The skills of yoga may improve mood. To find out, researchers (Streeter et al., 2010) assigned participants to one of two groups. In one, participants engaged in 60-

Does your current exercise program benefit your mood?

Other physical interventions also have the power to reduce anxiety. In massage therapy, pressure is applied to the body in order to manipulate, and relax, muscles and other soft tissues of the body. A statistical analysis of more than three dozen studies shows that massage therapy influences mood (Moyer, Rounds, & Hannum, 2004). Even single sessions of massage therapy reduce feelings of anxious tension.

The effects of exercise, yoga, and massage therapy teach a general lesson about mood. Your mood reflects the overall state of your body (Thayer, 2003). Changes in the condition of the body, then, directly influence mood.

MUSIC. Another activity that can affect your mood is music. Intuitively, you know that music can alter your feelings. An upbeat song peps you up. Hearing your favorite band can brighten a dull or depressed mood. Research backs up your intuitions.

Laboratory experiments reveal that music and mood are systematically linked (Krumhansl, 2002). In this research, participants heard passages of symphonic music that varied in tempo, rhythm, and tone. They reported experiencing different emotions during the different musical passages. Furthermore, physiological recordings (heart rate, blood pressure) showed that their internal bodily states varied across musical passages, just as you would expect if the sound of music was altering their mood (Krumhansl, 1997).

434

Brain imaging confirms the effect of music on inner states of the body. Pleasant and inspiring music activates brain regions associated with the experience of pleasurable, rewarding stimuli (Blood & Zatorre, 2001; Koelsch et al., 2006).

Finally, singing may have unique effects on mood as well. In a survey of college choir members, the large majority reported that singing improves their mood (Clift & Hancox, 2001). In research comparing the effects of singing with merely listening to choral music, singing produced greater increases in positive mood, in addition to increased levels of a protein that is part of the body’s immune system (Kreutz et al., 2004).

The effects of music on mood are puzzling, though. Why should a series of tones, patterned across time, affect people’s feelings? Psychological science cannot answer this question definitively. However, theorists suggest an interesting possibility (Scherer, 2004). Music may automatically activate body rhythms and movements that, in turn, influence your mood. When you hear some upbeat music, the rhythm and melody tend to induce body movement (such as bobbing your head). These movements are associated with positive mood; your body tends to move more quickly and vigorously when you’re happy than when you’re depressed. The body movement induced by music, then, may create a more positive mood (Scherer, 2004)—just as you might expect from research reviewed earlier on mood and physical activities.

Do you find it hard to resist moving your body when you hear music? If so, what is the effect on your mood?

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 10

Which of the following statements are true about factors that can change mood?

- Ht3PDiGzt/UDciE23/CPZtZnvwpgOx7qZoaOScBypxc/W6YXV8QWpKcYoN8aUFhGHYAtUUSNdtP05J01GEO2BHv0qAM5gIRBUdcobY78GHLLEp46fXTzxMoZGm4af0ah9H3pFDqwCJ2kXdEXLP0swi1DiiJiqJjZkTTZ3zwoGQkJkLn8NtgY3vic8VFFtsefvVQH57DeVbOR/2Id6deZw2zxV8Tq0LTPxc468bQXwAQXWRKu

- NnRD/N38hfWC8iX9lI5Hjuhys4j7CtZjTtWSPURtkqeHUaOTbj1ylAs5qAD3qKwsmBhzarofH9pRyOqkra0i1PRfiNib+9L7mDdYpzKm9H1fPaWDHaVtuP+X1zxPNAqQ5tq9OjVyRUZuExC0gy+3QjVxwO1mH+QG

- sfvFU8SyBKSEGseRWcIrpmeB8A69NaMnlMdWekewWoNxYlUyfSwZ6pi/rotS3iMazSeYPFn++QtLMy4QGUl/B6vYS4bm5XhJrVXG9/O3pM22m17iaTV9JRJwuEfLzz1AXtkR45Q6eJU=

- 2tZXtz/qeJzBgO9n6vsxFmuB6kW7WSGFw8fG0GUAE5sd4fFTGlXt9oCjcq9vzQ4CmBBG/uAVXQm9TOshhDMqCLk7hfvCb/1E+wpYoZT9/hUWrMtaUV6bja3rMhJkrqplfPaQUll62jhjX+7ZJOVwouWOyKDu8H3oL+F2WbY/Hhg+hHZiCgGkVkjHhyemiv9nG4SK+g==

Mood, Thought, and Behavior

Preview Questions

Question

Can today’s weather influence how satisfied we are with life in general?

Can today’s weather influence how satisfied we are with life in general?

Are people more likely to help others when in a positive mood or negative mood?

Are people more likely to help others when in a positive mood or negative mood?

Mood is inherently interesting. Variations in mood state intrigue psychologists and nonpsychologists alike. Yet, to the psychological scientist, mood is intriguing for a second reason, namely, because it systematically affects thinking and behavior. Let’s first look at the influence of mood on thought.

MOOD AS INFORMATION. Consider the following questions:

How much do you like the college in which you are enrolled?

How good is your car?

How satisfied are you with your life in general?

435

We posed those questions in order to ask you a different one: How did you go about answering them?

In theory, you might have answered each question by contemplating a long list of facts and then systematically adding the facts together. To answer the life satisfaction question, you could have written down a long list of every person, place, and thing associated with your life; weighed the good with the bad; averaged all the pieces of information together; and computed a level of life satisfaction. But, in reality, that’s probably not what you did.

When evaluating a target of judgment—

The mood-

The mood-

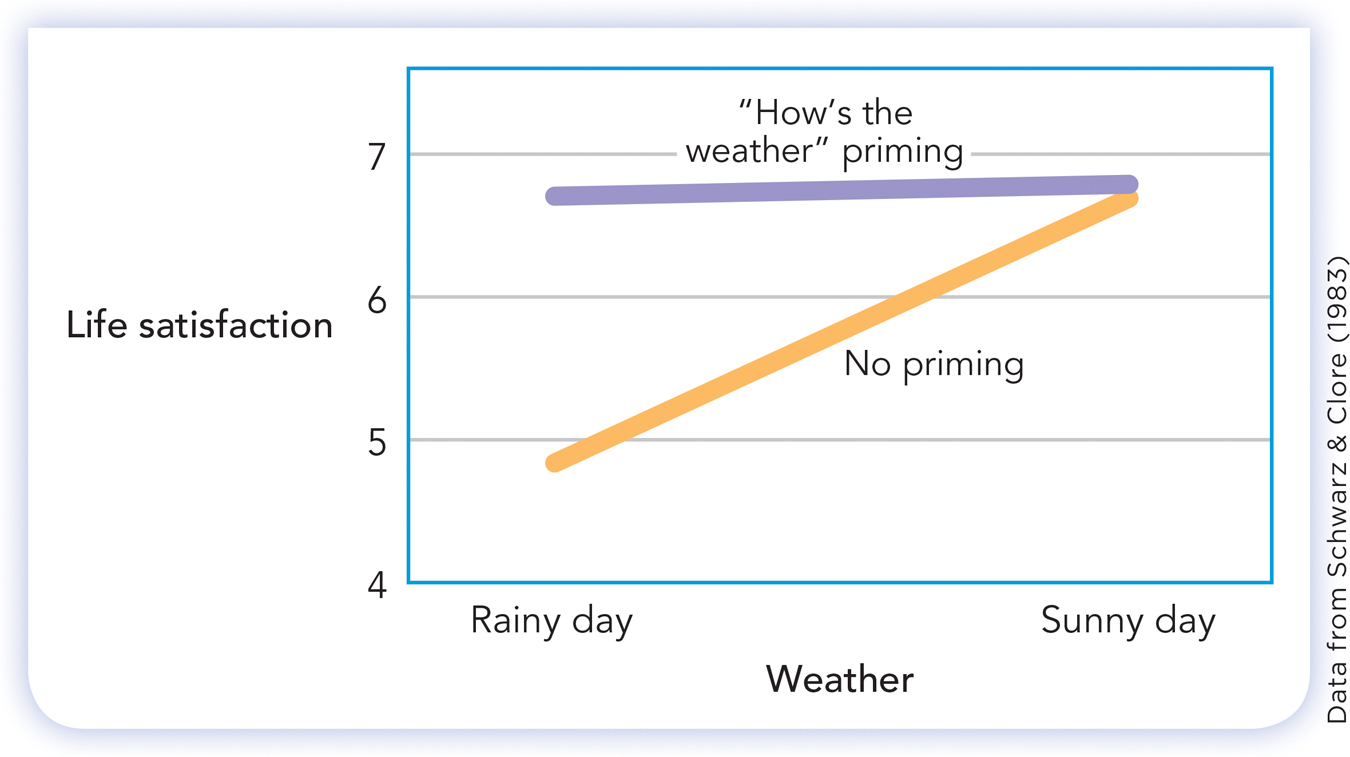

A study by the social psychologists Norbert Schwarz and Gerald Clore (1983) vividly illustrates mood-

Interestingly, if the researchers first asked participants, “How’s the weather?” their life evaluations on sunny and rainy days did not differ (Schwarz & Clore, 1983). The “how’s the weather” question reminded people that something irrelevant, the weather that day, might bias their judgments. Once reminded, participants no longer used their mood as a source of information. There’s a practical lesson here! When making an important life decision, stop and think—

MOOD AND HELPING. Mood can also influence behavior. How you feel affects what you do. One type of social behavior that is strongly influenced by mood is helping others.

People often have opportunities to help. Salvation Army workers ask for donations. Community service organizations seek volunteers. Indigent and homeless citizens ask for assistance. Do you help them? Research suggests that you are much more likely to do so if you are in a good mood.

436

Even simple, subtle influences on mood can affect willingness to help. Isen and Levin (1972) conducted a study in which they left a dime in the coin return slot of telephones in a phone booth. (This was well before the advent of cell phones, at a time when the value of a dime was equivalent to about 50 cents in today’s money.) After participants found the dime and left the booth, a researcher nearby would drop a folder full of papers on the ground. The dependent measure of the study was whether participants helped pick up the papers. Finding a dime—

Can any of your acts of generosity have been influenced by something as small as a dime?