10.5 Stress and Health

Some emotions are relaxing: the calm tranquility your experience lazing under a warm sun. Some are uplifting: the pride and sense of power you experience after winning a big game. But some emotions are stressful. Tragic news (the death of a loved one), physical threats (a mugging), personal challenges (an upcoming exam), and interpersonal crises (a relationship break-

In this final section of the chapter, we’ll look at the nature of stress, how it can affect the body and your health, and how you can cope with the stresses of life.

Stress

Preview Questions

Question

How do psychologists classify environmental stressors? Are they always negative?

How do psychologists classify environmental stressors? Are they always negative?

What psychological features determine whether we experience a given environment as stressful?

What psychological features determine whether we experience a given environment as stressful?

Through what biological process do our bodies enable us to respond adaptively to stress?

Through what biological process do our bodies enable us to respond adaptively to stress?

What is the role of hormones in the stress response?

What is the role of hormones in the stress response?

The word “stress” can be used in three different ways. It can refer to (1) environmental events, (2) subjective feelings, and (3) bodily reactions, specifically, the body’s response to stressful events. Let’s look at all three.

ENVIRONMENTAL STRESSORS. An environmental event is called a “stressor” if it is potentially damaging to an individual. Researchers distinguish among three types of environmental stressors (Lazarus & Lazarus, 1994):

Harms are damaging events that have already occurred. The recent death of a family member or close friend would be a stressful harm.

Threats are potentially damaging events that might occur in the future. If you’re walking at night and see someone who looks dangerous walking toward you, the potential danger he represents is a threat.

Challenges are upcoming or ongoing activities that pose obstacles which, if overcome, can lead to personal growth. If you are working on a big exam, there not only is a threat of failing; there also is an opportunity to solve the exam’s challenging problems and thereby prove your abilities to yourself.

In addition to the three types of stressors, stressors—

These distinctions identify different types of stressors. What specific life events, though, tend to be most stressful? Psychologists have developed lists of stressful life events, ranked according to the degree to which they disrupt established patterns of life (Holmes & Rahe, 1967). As you can see (Table 10.2), they include not only negative events (e.g., personal injury, being fired from work) but also some positive ones (e.g., an addition to the family) that require life adjustments that may present major challenges.

Have you experienced a lot of these events? Let’s hope not! They are life events that cause stress because they disrupt established patterns of life. The stress scores indicate the typical degree of disruption (Holmes & Rahe, 1967).

10.2

| Stressful Events | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Event |

Stress Scores |

Event |

Stress Scores |

|

Death of spouse |

100 |

Change in work responsibilities |

29 |

|

Divorce |

73 |

Trouble with in- |

29 |

|

Marital separation |

65 |

Outstanding personal achievement |

28 |

|

Jail term |

63 |

Spouse begins or stops work |

26 |

|

Death of close family member |

63 |

Starting or finishing school |

26 |

|

Personal injury or illness |

53 |

Change in living conditions |

25 |

|

Marriage |

50 |

Revision of personal habits |

24 |

|

Fired from work |

47 |

Trouble with boss |

23 |

|

Marital reconciliation |

45 |

Change in work hours, conditions |

20 |

|

Retirement |

45 |

Change in residence |

20 |

|

Change in family member’s health |

44 |

Change in schools |

20 |

|

Pregnancy |

40 |

Change in recreational habits |

19 |

|

Sex difficulties |

39 |

Change in church activities |

19 |

|

Addition to family |

39 |

Change in social activities |

18 |

|

Business readjustment |

39 |

Mortgage or loan under $10,000 |

17 |

|

Change in financial status |

38 |

Change in sleeping habits |

16 |

|

Death of close friend |

37 |

Change in number of family gatherings |

15 |

|

Change to a different line of work |

36 |

Change in eating habits |

15 |

|

Change in number of marital arguments |

35 |

Vacation |

13 |

|

Mortgage or loan over $10,000 |

31 |

Christmas season |

12 |

|

Foreclosure of mortgage or loan |

30 |

Minor violation of the law |

11 |

|

Reprinted from Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11: 213– |

|||

What positive life events have you experienced that required life adjustments?

SUBJECTIVE STRESS. Stress must be understood not only from the outside—

People experience subjective stress when situational demands and personal resources are out of balance (Lazarus & Lazarus, 1994). If demands outweigh resources (“I can’t figure out these calculus problems—

Measures of subjective stress differ from tests designed to measure environmental stressors (see Table 10.2). Subjective stress is measured using test items such as the following (Horowitz, Wilner, & Alvarez, 1979):

“I have difficulty falling asleep because of images or thoughts related to the event.”

“Things I saw or heard suddenly reminded me of it.”

“I stayed away from things or situations that might remind me of it.”

These items tap personal responses to stressful circumstances. They enable psychologists to identify individual differences in subjective reactions to the same objective event.

PHYSIOLOGICAL STRESS REACTIONS. “Stress” also refers to physiological reactions. When you experience a stressor, your body reacts. It produces a stress response, a coordinated series of physiological changes that prepare you for “fight or flight,” that is, to confront or flee the stressor (Rodrigues, LeDoux, & Sapolsky, 2009).

The physiological changes that comprise the stress response occur in multiple systems within the body. Your heart rate increases, which delivers more oxygen to muscles to fuel bodily movement. Your thinking changes; signals from body to brain cause your attention to focus in on the stressor. Your immune system alters its functioning; as we discuss in detail below, this change means that stress can affect your health.

In the mid-

Alarm reaction: When a stressor first occurs, the body’s “internal alarm” system goes off, preparing the organism for fight or flight.

Resistance: If a stressor continues to be present—

that is, if it is a chronic stressor— our bodies adapt. Our immune systems respond to the environment’s high demands by “working overtime” to protect the body. Exhaustion: The resistance stage requires energy. If a chronic stressor persists long enough, we run out of bodily energy and experience exhaustion. Immune system functioning breaks down, bodily organs can become damaged, and we are at high risk of illness.

The biological mechanisms that enable the body to respond adaptively to stress involve hormones, chemical substances that travel throughout the body and influence the activity of bodily organs (Chapter 3). When a stressful event occurs, hormones make intelligent use of the body’s overall energies (Sapolsky, 2004). Hormones increase the supply of blood sugar and oxygen, which gives you extra energy to either flee from or confront the stressor. They suppress physiological activities that don’t help you cope with the stressor; for example, under stress, digestive processes and sexual drives are reduced. This makes sense in evolutionary terms. Over the course of evolution, if you were under threat from a predator, that was no time to sit around digesting food or having sex.

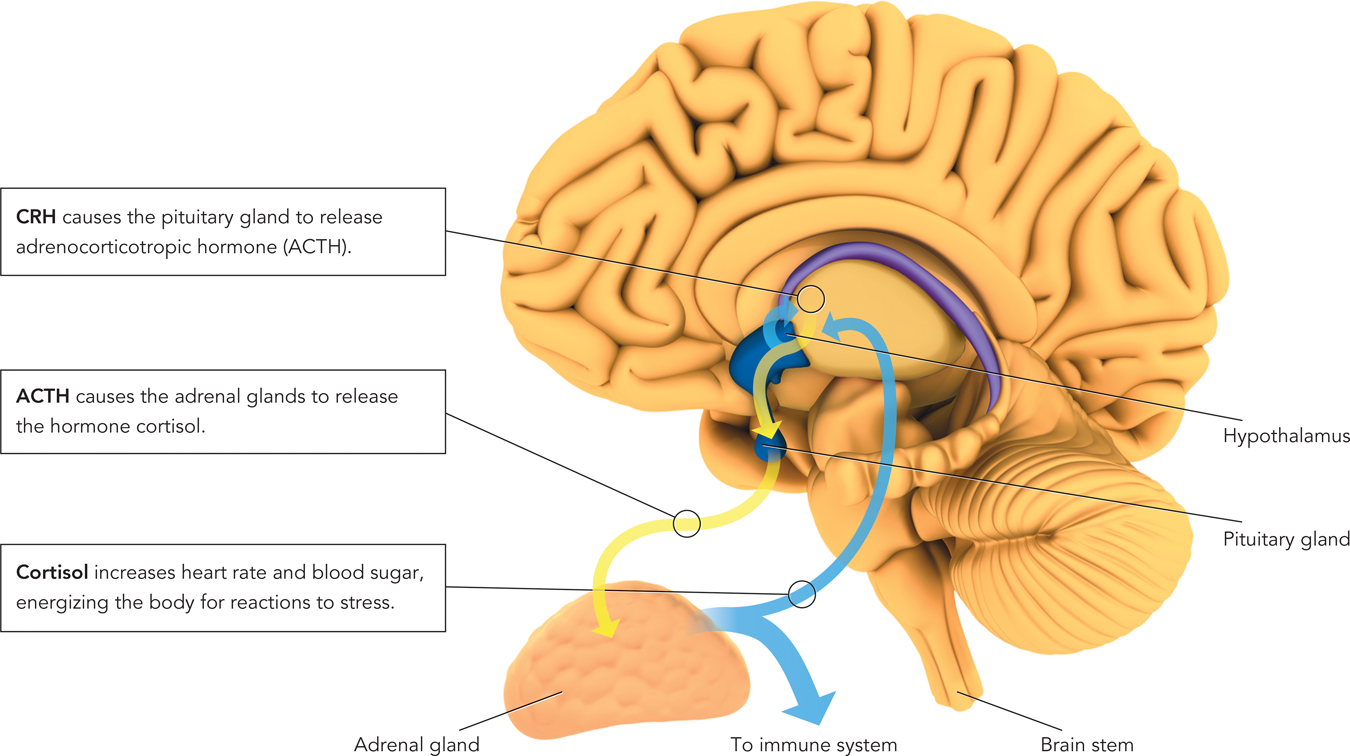

Which exact hormones and bodily organs are involved in stress reactions? The central system is the hypothalamic–

The hypothalamus releases a hormone, corticotropin-

releasing hormone (CRH), into a duct that leads to the pituitary gland.CRH causes the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH is carried by the bloodstream to the adrenal glands.

- Page 445

ACTH causes the adrenal glands to release another hormone, cortisol, into the bloodstream. Cortisol increases heart rate and blood sugar, thus energizing the body to react to stress.

The HPA axis also has a feedback mechanism. Some of the cortisol from the adrenal glands makes its way back to the hypothalamus and inhibits further hypothalamic release of CRH. This prevents the body as a whole from overreacting to the stressor (Sternberg & Gold, 1997).

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 15

When we perceive that situational demands are not in with personal resources, we experience stress. The first stage of the general syndrome (GAS) is the reaction, followed by , during which time our immune system works overtime to protect us. If the stressor continues, we experience the final stage of the GAS, . During a stress reaction, the –pituitary–

Health Effects of Stress

Preview Questions

Question

How does stress affect the functioning of our immune system? What are the implications for health?

How does stress affect the functioning of our immune system? What are the implications for health?

How can researchers test the effects of stress on immune system functioning in a way that controls for how hectic one’s life is?

How can researchers test the effects of stress on immune system functioning in a way that controls for how hectic one’s life is?

How can stress make us old before our time?

How can stress make us old before our time?

How does stress influence health? A primary way is through the effects of stress on the immune system.

STRESS AND THE IMMUNE SYSTEM. Your body generally is good at protecting itself. A set of bodily processes, the immune system, protects against germs, microorganisms, and other foreign substances that enter the body and can cause disease.

Stress can disrupt the normal functioning of the immune system. The link from stress to immune functioning is the HPA axis. Immune system response is affected by cortisol, the hormone released by the adrenal glands (Sternberg & Gold, 1997).

Different types of stressors have different effects on immune functioning. The key difference is whether the stressor is a short-

A meta-

Have you experienced more illness during times of chronic stress?

STRESS AND HEALTH OUTCOMES. As you would expect, when the immune system is impaired, people experience poor health (Lovallo, 2005). Nurses who work for years on night shifts experience more heart disease (Kawachi et al., 1995). People who care for relatives with dementia are slower to heal from physical wounds (Kiecolt-

Psychologists have linked stress to health through two types of research strategies. One is correlational; researchers determine whether levels of stress correlate with later health outcomes. For example, in the study of marital stress, correlational findings indicate that high levels of marital distress predict high numbers of physician visits, higher levels of self-

Correlational studies are informative but not entirely convincing. They leave open two possibilities. One is that stress directly impacts health. The other is that stress impacts health only indirectly; for example, highly stressed people may lead more hectic lifestyles that expose them to more people and thus more viruses. This exposure—

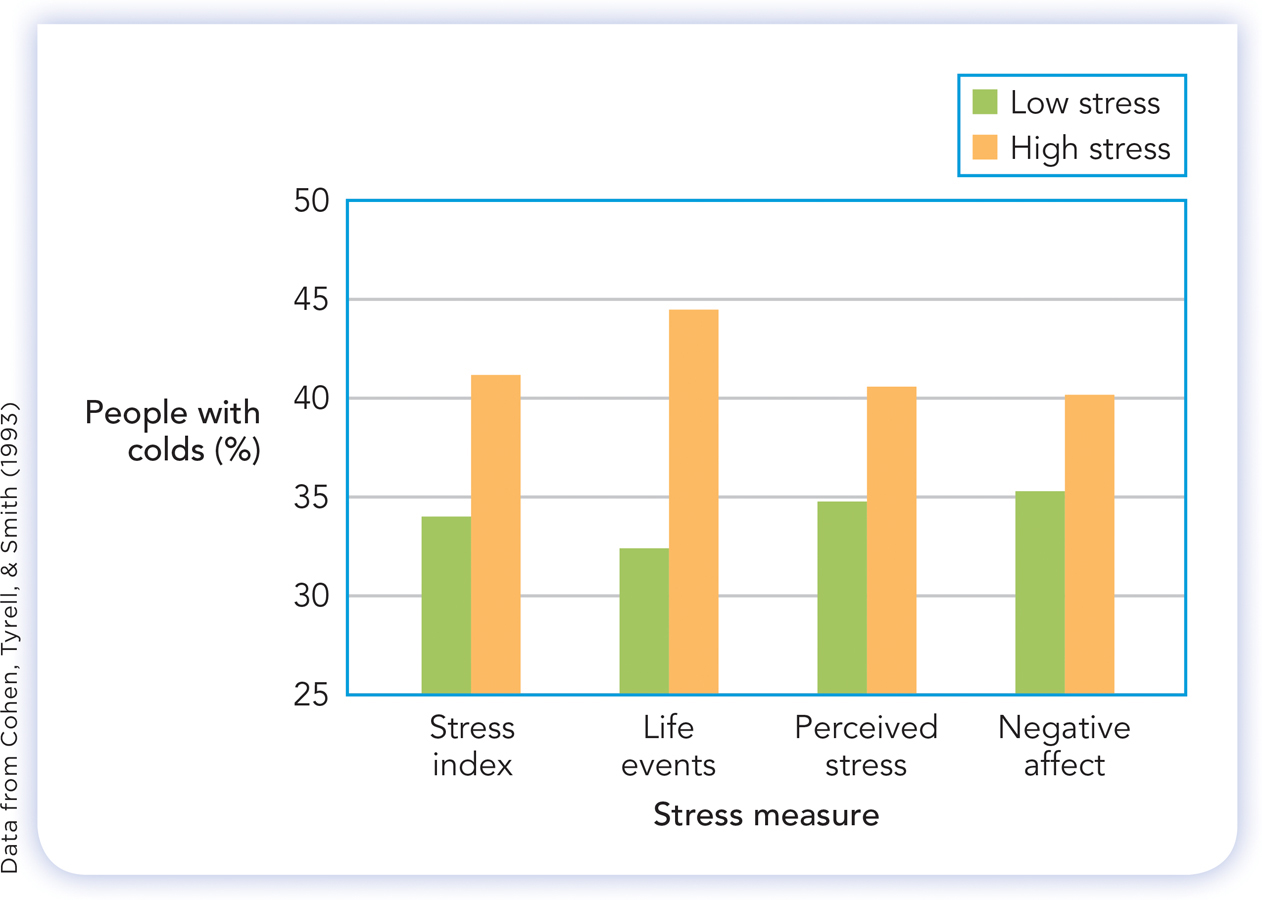

In the second strategy, researchers experimentally manipulate people’s exposure to viruses. Sheldon Cohen and colleagues randomly assigned participants to conditions in which they received nasal drops containing (1) a respiratory virus or (2) a simple mixture of salt and water (Cohen, Tyrrell, & Smith, 1993). Participants were quarantined in their apartments for two days before and seven days after receiving the drops. Each day, a physician examined each participant and recorded signs of illness. In addition, Cohen and colleagues measured stress. Participants indicated the number of stressful life events they were experiencing and whether they believed that these stressors exceeded their ability to cope. This sophisticated research strategy demonstrated that stress directly predicts health; among those exposed to the virus, people with more stressful lives were more likely to develop colds (Figure 10.17).

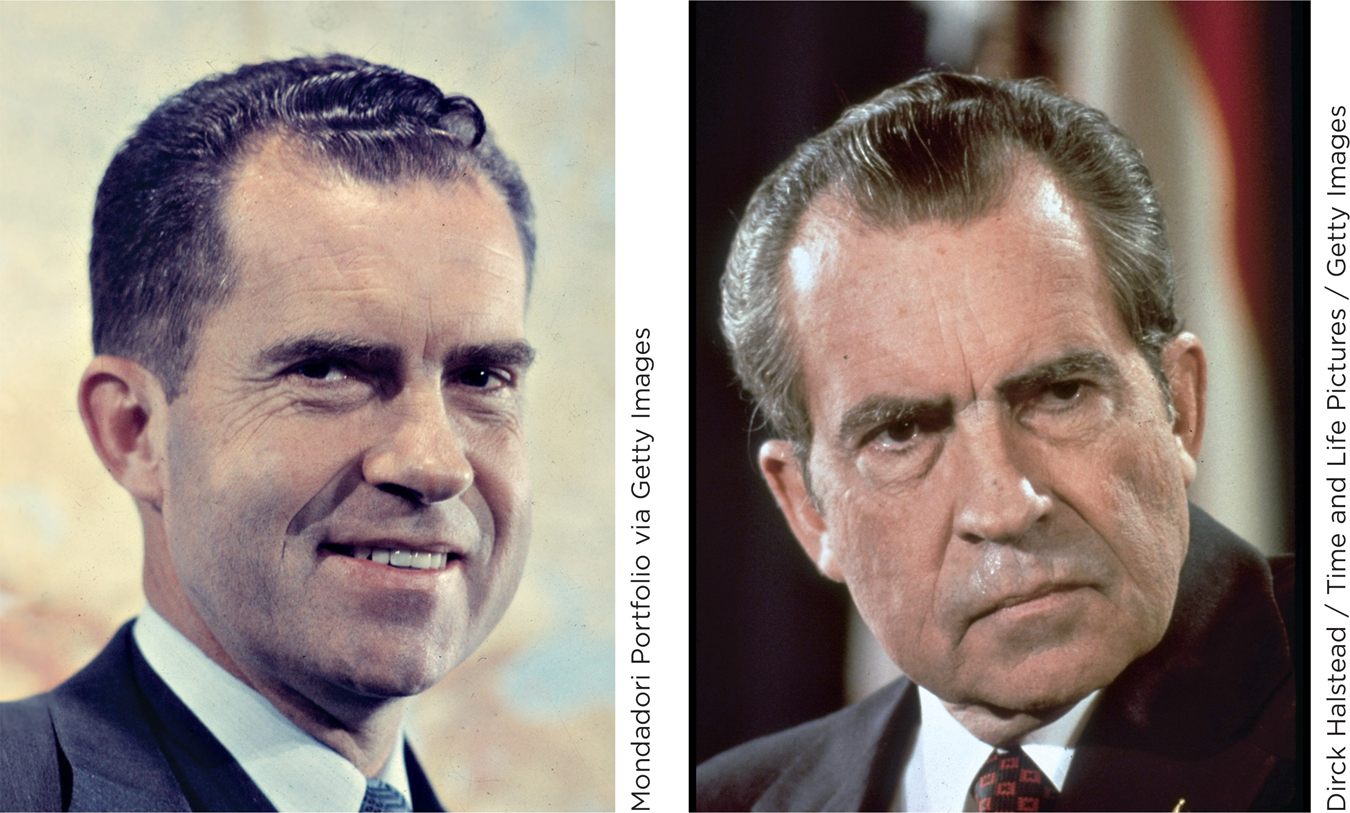

STRESS AND THE RATE OF AGING. When he served as vice president of the United States, an energetic, youthful Richard Nixon—

In part, it was the natural effects of aging (Olshansky, 2011). But the stress couldn’t have helped. Life stress can accelerate the rate at which people age. Stress influences aging by affecting small bits of DNA called telomeres (Epel et al., 2004).

DNA, which is contained in chromosomes in the nuclei of cells, is the molecular material that contains the genetic instructions used to build organisms. A telomere is a small strand of DNA at the end of each chromosome. Telomeres maintain a cell’s “youthfulness.” When a cell loses too much of its telomere, it cannot replicate. Evidence suggests that, when this happens, body tissues age more rapidly (Sanders & Newman, 2013).

Research shows that stress can alter the body’s internal chemistry in a way that causes telomeres to shorten (Epel et al., 2004). The researchers studied a group of mothers, some of whom experienced the stress of caring for a chronically ill child. They measured the level of stress experienced by each mother and, by analyzing blood samples, also measured telomere length. Mothers with higher levels of stress had shorter telomeres. They were old before their time.

Research on stress and telomeres reveals, once again, the intimate connections between body and mind, and the interplay among person-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 16

Over 300 studies confirm that -term stressors increase immune system functioning, whereas -term stressors decrease its functioning. The consequences of impaired immune system functioning include disease, slower wound healing, and decreases in longevity. Experimental research indicates that directly impairs health. Stress ages us by shortening , the strand of DNA at the end of each chromosome that maintains a cell’s youthfulness.

Coping with Stress

Preview Questions

Question

When coping with stressful events, is it more advantageous to try to change the problem or to focus on one’s emotions?

When coping with stressful events, is it more advantageous to try to change the problem or to focus on one’s emotions?

How and why do men and women’s coping strategies differ?

How and why do men and women’s coping strategies differ?

How is social support beneficial to physical and mental health?

How is social support beneficial to physical and mental health?

How do you deal with stress? Some of the following strategies (from Internet discussions) might sound familiar:

“When I am stressed, I cope by writing or sleeping.”

“I cope by simply walking out the door and sitting quietly in a nearby coffee shop, nursing a local drink until my anger and stress subside.”

“I cope by focusing on one task at a time…multitasking is just beyond me right now. So, I look at my day’s to-

do list, and prioritize things based on importance and the energy level required.” “When I am stressed I cope by eating. If I’ve just come away from a stressful conversation or feel overwhelmed by everything I need to do, my stress reliever is to pause and have a little snack. Wow, if I am having a very stressful day or week, you can imagine how those extra unnecessary calories can add up!”

“Well personally, I get extremely stressed with all the work I get. I’m in a couple of AP’s right now and those stress me out incredibly. I cope by getting my work done early so I get sleep.”

“I cope by playing Electric Avenue on repeat and eating Grape Nerds.”

You’re probably thinking that some of these coping strategies are better than others. You might also have noticed that they are of two different types: problem-

PROBLEM-

Problem-

focused coping is an effort to change some aspects of the problem that is causing stress, so the problem is more manageable.Emotion-

focused coping is an effort to alter one’s own feelings, which have been affected by a stressful problem, rather than altering the problem itself.

Look back to the examples of coping we presented above. You can tell which type of coping each exemplifies. “Prioritize things based on importance” is problem-

Which way of coping is better? It depends; “coping processes are not inherently good or bad” (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004, p. 753). Focusing on problems to be solved is often advantageous. Yet sometimes—

Research points to the advantages of coping flexibly: adjusting your coping style to the possibilities available in the situation at hand. One researcher (Cheng, 2001) measures flexibility by asking people how they have coped with a variety of different stressors that occur on different days. Some people, she finds, tend to cope in the same way from one situation to the next. Others are more flexible; they adjust coping strategies to different situations. Findings show that people who cope flexibly are less anxious when a highly stressful event, such as a major health problem, occurs (Cheng, 2003). Workers who are taught strategies for coping flexibly (e.g., using emotion-

CONNECTING TO BRAIN SYSTEMS AND PSYCHOLOGICAL THERAPIES

GENDER DIFFERENCES IN COPING. When it comes to coping with stress, men and women differ. To see the difference, we have to distinguish between two types of coping responses: fight-

Many members of the animal kingdom display a fight-

The psychologist Shelley Taylor and colleagues (Taylor et al., 2000) explain that women often cope in ways that are neither fight nor flight. Instead, women often tend-

Tending: Taking action to reduce the distress and increase the safety of others, especially one’s offspring

Befriending: Maintaining close personal connections with other people whose support might be helpful in coping with stress

Women are more likely than men to tend and to befriend. For example, compared with men, women have more same-

Why do men and women differ? Taylor suggests that biological evolution provides the answer. Across the course of evolution, females have been more heavily involved in parenting than males. During pregnancy, females carry the offspring. Afterward, they provide more biological support during nursing. For females, then, fight-

SOCIAL SUPPORT. Taylor’s analysis of befriending raises a key point: When coping with stress, you don’t have to go it alone. Friends and family can reduce the impact of stressful events by providing loving care and personal assistance, or social support. Research shows that people who receive more social support during times of stress tend to experience better physical and mental health (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Taylor & Stanton, 2007).

Psychologists have identified two ways in which social support is beneficial (Cohen & Wills, 1985). One is stress buffering. When stressful events occur, support from others can lower—

Social support’s other benefit occurs even before you experience stress. Large networks of supportive friends and family increase people’s overall psychological wellbeing. Increased well-

Research documents the impact of social support in multiple areas of life. One is intimate relationships. Psychologists suggest that one key to the success of relationships is the social support that partners provide one another (Reis & Patrick, 1996). When partners make each other feel understood and emotionally supported, relationships thrive. In a study of remarkable scope, researchers studied couples over a 10-

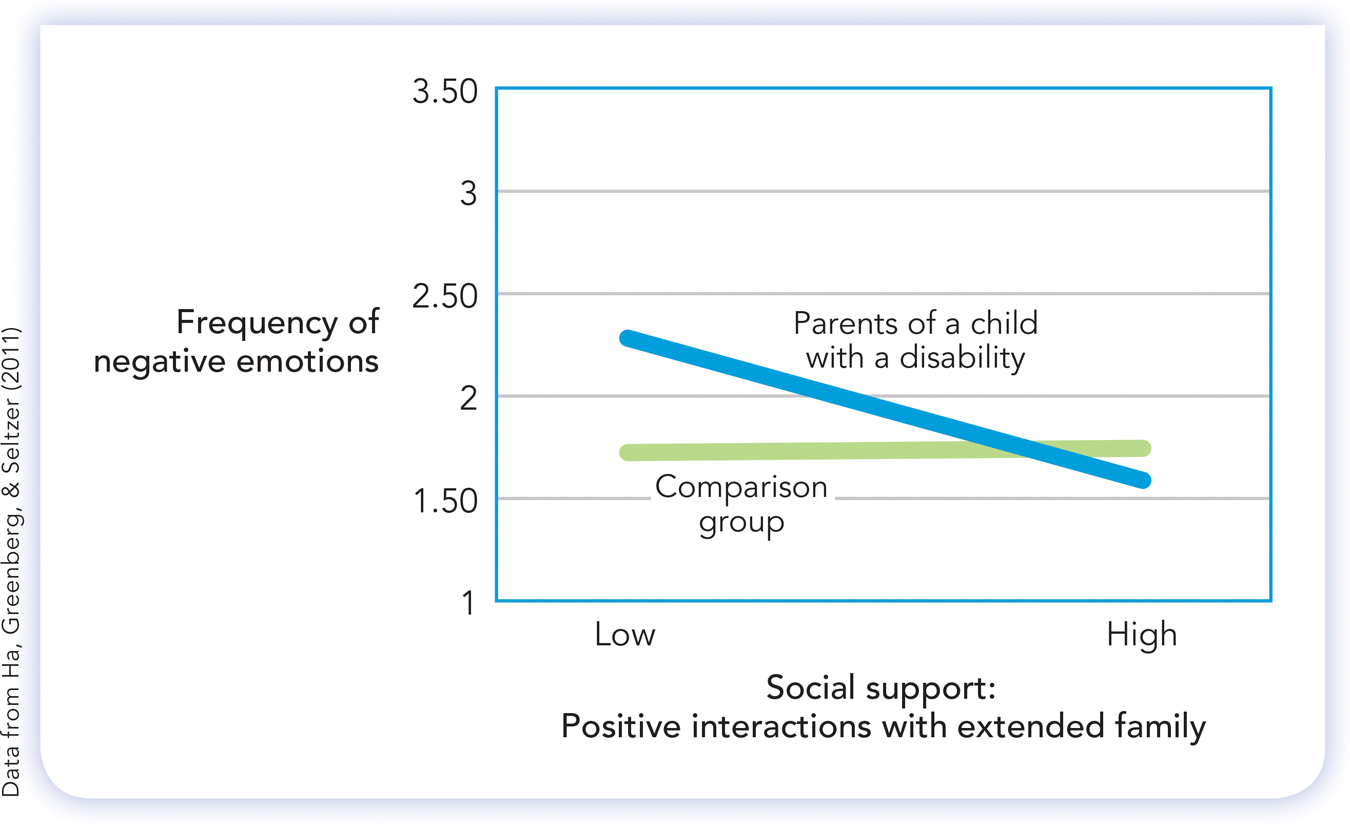

Another area where social support brings benefits is parenting. Parenting can be stressful for anyone, but is particularly so for parents of children with disabilities. In one research project (Ha, Greenberg, & Seltzer, 2011), African American parents of children with disabilities such as autism (a disorder in which children fail to develop normal interactions with other people; see Chapter 14) and epilepsy (a nervous system disorder in which people experience seizures), plus a comparison group of parents whose children had no disabilities, were studied over a number of years. This group of parents was of particular interest because African American communities often contain extended families whose members provide one another with substantial social support.

A key dependent variable in this study was the emotional state of parents; the researchers measured negative emotion experienced by parents with, and without, children with disabilities. As you can see in Figure 10.18, social support buffered parents against negative emotions. Consider the parents of children with a disability. Among those with low social support, stressful negative emotions were frequent. But among those with high levels of social support, negative emotions were no more frequent than they were among other parents.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 17

True or False?

The effectiveness of problem-

focused and emotion- focused coping strategies depends on whether you have control over the stressor. A. B. Researchers advocate we cope flexibly, by adjusting our strategies to the type of problem.

A. B. Men, more often than women, use the tend-

and- befriend strategy, which involves reducing others’ distress and maintaining a social support network. A. B. Research demonstrates that social support can contribute to physical and mental health by buffering the impact of a stressor.

A. B.