11.6 Motivation in Groups

Most of the motivation research we’ve covered so far in this chapter focuses on the individual. An individual person is struggling to control her diet, is being challenged on a laboratory task, or is being beeped in an experience sampling study. But much of motivation occurs in groups. Whether at work or at play, people are observed by others, compete with others, and team up with others. Let’s look, then, at interaction with others.

Social Facilitation

Preview Question

Question

Does the presence of others improve or worsen performance?

Does the presence of others improve or worsen performance?

Back in the 1890s, psychologist Norman Triplett (1898) noticed something interesting about bicycle racers. When they rode as fast as possible on a track by themselves, they were slower than when they rode as fast as possible in a race with others. What he observed is a phenomenon known as social facilitation, a motivational phenomenon that occurs in groups. In social facilitation, the mere presence of other people improves people’s performance on tasks on which they are skilled (Aiello & Douthitt, 2001). Social facilitation does not make a person skilled; if you don’t know how to ride a bike, you won’t suddenly be able to ride if other people are watching. However, it does enhance motivation. If you’re a skilled bike rider and you’re trying to pedal at maximum speed, the presence of others—

Triplett (1898) conducted an experiment to test the effects of others’ presence on motivation. Ironically, his own experiment did not provide strong evidence of social facilitation effects, a fact that only became clear when contemporary researchers analyzed his data with modern statistical methods that were lacking in his day (Stroebe, 2012). But the phenomenon is real; in many settings, social facilitation does boost motivation and performance.

Clear evidence of social facilitation effects came from a classic paper by the social psychologist Robert Zajonc (1965), whose review of social facilitation research accomplished three major goals. First, Zajonc showed that social facilitation occurs in not only humans, but also other organisms. Humans, rats, chickens—

On what tasks has the presence of others improved your performance? On what tasks has the presence of others decreased your performance?

Can you think of an exception to the social facilitation principle that the presence of others improves performance? This question might help: Have you ever worked on a group project for class and noticed that, while you were working hard on the project, somebody else in your group was playing video games? That person was displaying social loafing, a reduction in motivation on group tasks in which people work together. Groups often reduce the motivation of people who expect that, thanks to others’ efforts, the group is likely to succeed, even if they goof off (Karau & Williams, 1993).

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 18

Which of the following statements accurately describe Zajonc’s findings from his work on social facilitation?

- DZ4VxWGh4GaU0sPKO9e/SiYiAWI524qflFQ2YI5yAvWx87gPc+KLMoi8/Zq6dXUSXKdvhR5myvA9OL8VIUYbp5zbsW/Ma6PIaBcQHFRiiWCoFq6h9k4ZqtA8dq/ja90f

- r7zKrFlr0d54N4h608814KbwTKzcqZcJWAlJxxc7FQLokgsGfr95U0sayHvsAmS/h6xC2qfv+ZWOqD6L5r6pW2Jed3iA1yeoD0sSQ5cAR6usiwMyxjD8hcn3nLB8VxEqAxgGxgzgWNam8UWeBDv+Z16OJCAm4xP6

- XlT5B6G4ROfaGeVkr79xx6OnkzEnMvxGBPMc7KjdLlUTrmVlxtpbuB2EpkElZg+y5r9hCGMYc6TLJh+36/cUYNQwPFfSN8iz42mAimUVrWBw4Kx7HYJg2rZwn+rUuuhiU2nTopOAS7LLATgX1KHvKg==

- yCz3avbmBUCPqtPRZhJf/JRiGf2Y6P2jjTxgVZDLPxlQzzieiOKHYuS0SC9FKzceAvmz6hBTEfFS2IaS7qemRmfvNSClfpx3Qbpp/Fk/N+0gCKo4FPzOO3aXqfq0XPGq

Motivation in Schools

Preview Questions

Question

Do school grades measure intelligence or self-

Do school grades measure intelligence or self-

How can teachers increase students’ motivation?

How can teachers increase students’ motivation?

If you’re like most people, a large percentage of your waking hours have been spent in a group setting in which you are supposed to be motivated to achieve: school. U.S. schoolchildren spend about 32.5 hours a week at school, plus more time doing homework (Juster, Ono, & Stafford, 2004).

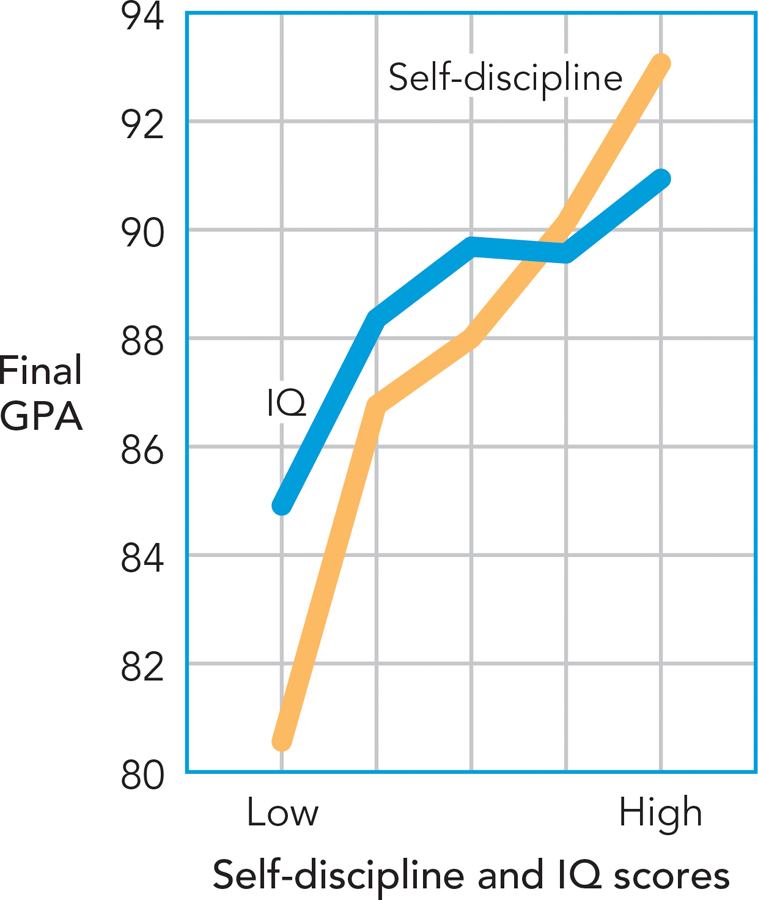

MOTIVATION AND GRADES. How important is motivation to school achievement? You might think that grades are just a matter of smarts; maybe some kids have a lot of intelligence and get good grades, and motivation makes little difference. But consider the following study. At the beginning of an eighth-

The results are shown in Figure 11.9. If intelligence predicted grades and self-

This study’s findings are consistent with other research. For example, in a study of high school students, study time was found to predict grades about as strongly as intelligence did (Keith, 1982).

INCREASING STUDENT MOTIVATION. How can teachers increase students’ motivation? Motivational processes you read about earlier in this chapter are relevant to the classroom (Covington, 2000). One important motivational process involves goals. Students who set a goal of learning and mastering material, rather than merely earning high grades, often achieve greater success (Ames, 1992; Nicholls, 1984). Goals are particularly important when students are struggling to learn material. Those aiming for high grades may worry that they aren’t smart enough, whereas those whose goal is to learn will recognize that the struggles are a natural part of learning (Dweck, 1986). The mindset program described earlier in this chapter, in which students are taught about how the brain makes new connections when learning, is designed in part to alter students’ goals (Dweck, 2006). Once students learn how the brain changes with experience, they may be less concerned about their current level of “smarts” and more focused on putting in the effort to learn material and develop a more powerful brain.

491

Others emphasize that goals are only part of the story of motivation in schools. Students—

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 19

Self-

Motivation at Work

Preview Questions

Question

What payment plan should you adopt if you want to motivate your employees?

What payment plan should you adopt if you want to motivate your employees?

What type of leadership style is most motivating?

What type of leadership style is most motivating?

After they’re done with school, most people spend much of their time in another group setting: work. Employment commonly immerses workers in complex organizations in which people work as teams—

PAY. What motivates employees at work? At the risk of stating the obvious, a big part of the answer is pay. Yet there are some nonobvious facts about how pay motivates employees. Consider the question of what type of payment plan is best for motivating employees: pay based on (1) the amount of time an employee spends on a job, (2) the amount of work the employee produces, or (3) the success of the company as a whole? There is no single, correct answer in all cases. Different payment plans work best in different work settings (Helper, Kleiner, & Wang, 2010).

In some jobs, any given employee individually produces a product (or stand-

alone part of a product) that a company sells. In these jobs, the most motivating pay systems focus on the individual employee. Companies can maximize their productivity by paying individuals according to the amount of work each produces. Different individuals, who work at different rates, may earn different amounts. In other jobs, people work in coordinated teams that jointly strategize, solve problems, and produce a product. In these settings, the optimal payment plan focuses on the group. Companies can maximize productivity by paying everyone in the group roughly the same amount of money, and providing pay raises based on the success of the group as a whole. When people work in teams, group payment plans increase their motivation and satisfaction with their jobs.

492

GOALS. Success at work requires not only wanting to do well, but also knowing what to do. In job settings, employee motivation and performance are increased by the setting of goals. The goal-

LEADERSHIP STYLES. Another factor that can affect workplace motivation is leadership style, the typical behavior and overall approach to managing employees that is adopted by managers in charge of a work group. Early research on leadership styles contrasted (1) democratic styles, in which everyone (leader and subordinates) participates in setting organizational goals; (2) autocratic styles, in which the leader dictates what others do; and (3) laissez-

Although different styles may be effective in different types of groups, in general, transformational leadership has significant advantages. Inspiring transformational leadership predicts greater employee motivation and greater satisfaction with the leader (Judge & Piccolo, 2004). Interestingly, women in leadership roles are somewhat more likely to be transformational-

What leadership style do you find most appealing?

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 20

You manage a small company that employs potters to make handmade ceramic pieces, such as mugs, bowls, and plates. Every item the workers produce is a stand-