Chapter 12 Introduction

How could human behavior be described? Surely only showing the actions of a variety of humans, as they are all mixed up together. Not what one man is doing now, but the whole hurly-burly.

– Ludwig Wittgenstein

PERSON

12 Social Psychology

13 Personality

14 Development

15 Psychological Disorders I

16 Psychological Disorders II

Social Psychology 12

CHAPTER OUTLINE

Social Behavior

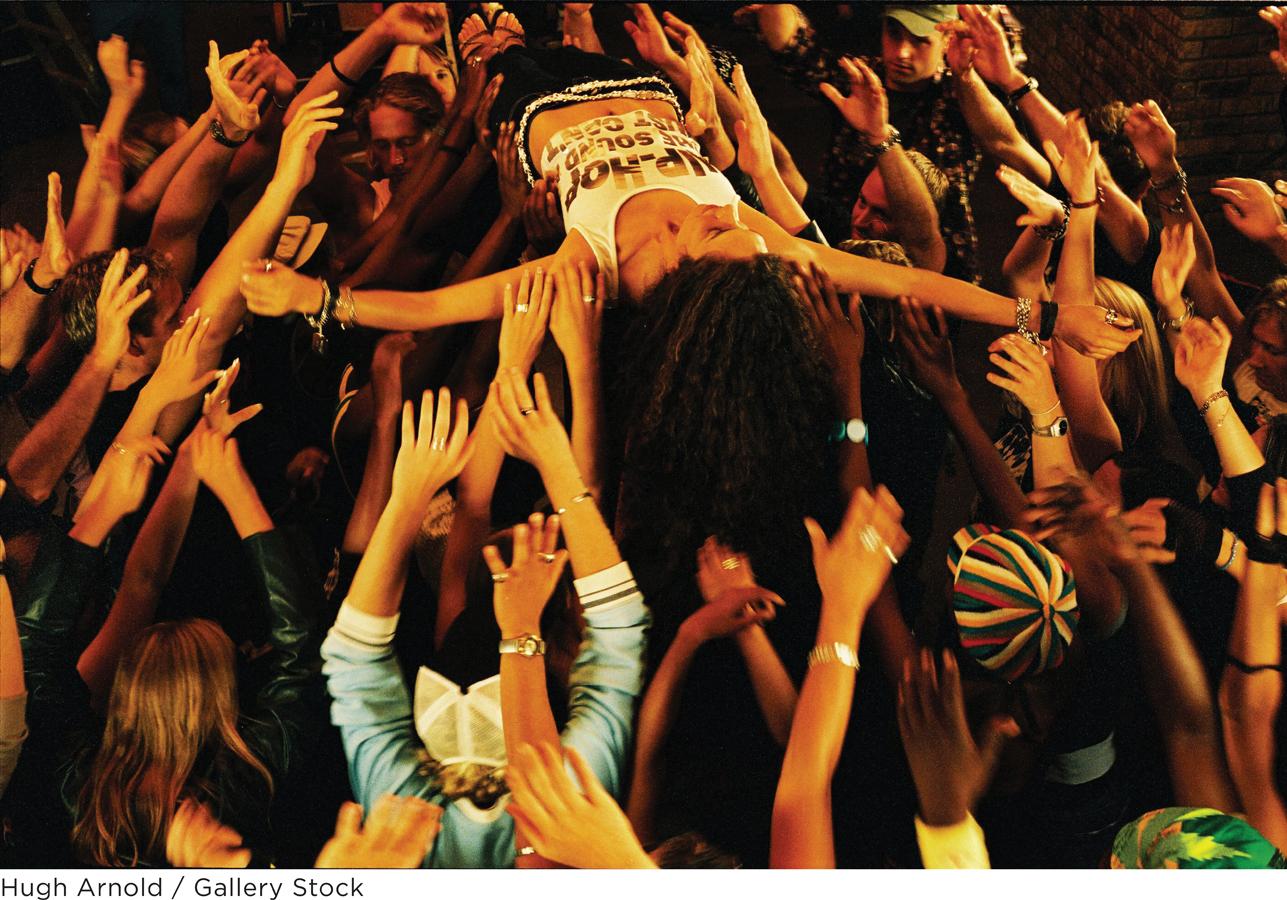

Crowds

Groups and Social Influence

RESEARCH TOOLKIT: Confederates

Roles and Group Identity

Close Relationships

Social Cognition

Attributions

THIS JUST IN: Attributions—

Causes or Reasons? Attitudes

Stereotyping and Prejudice

Culture

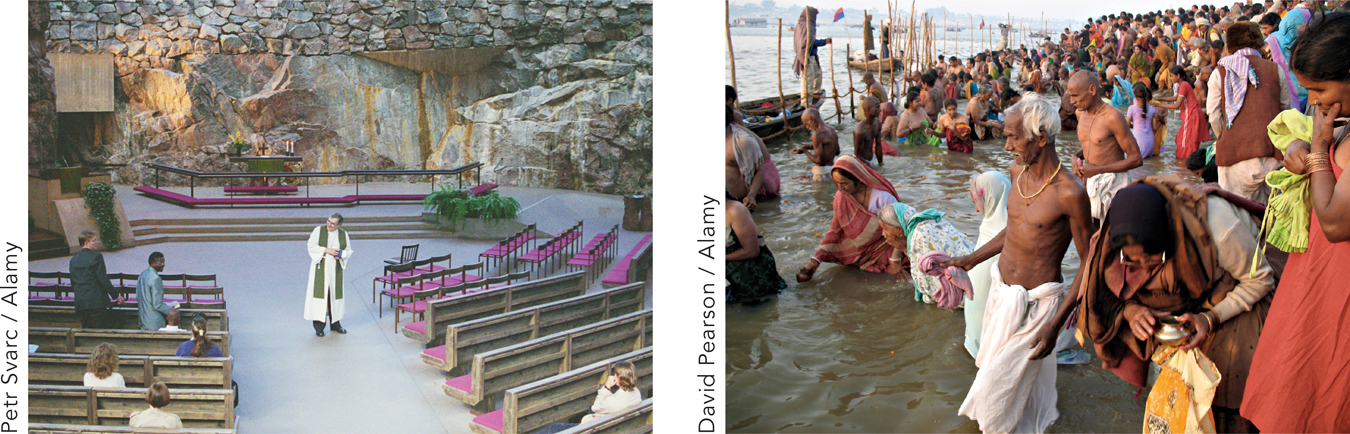

Cultural Variability in Beliefs and Social Practices

Cultural Variability in Social Psychological Processes

CULTURAL OPPORTUNITIES: Social Psychology

Culture and Attribution to Personal Versus Situational Causes

Social Cognition and the Brain

Thinking About Others’ Ongoing Experiences

Thinking About Others’ Enduring Characteristics

Looking Back and Looking Ahead

HOW CAN WE UNDERSTAND THE PSYCHOLOGY OF HUMAN BEINGS? A natural first step is to look at what humans do. Here are some examples of human behavior:

Nearly two-

thirds of Americans help others by donating to charity. Total annual donations are about $300 billion— roughly $1000 per person. In Brooklyn, New York, a woman in a hospital emergency room waited nearly 24 hours for medical care. Hospital staff saw her waiting but provided no help—

even as she fell to the floor, suffered convulsions for about an hour, and died. In Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, roughly 9 out of 10 citizens “never or rarely” attend religious services.

In Allahabad, India, organizers held a religious festival at a place where legend says that divine nectar once fell to Earth while gods and demons wrestled over a water pitcher. More than 80 million people attended.

A poll in the United States indicates that 40% of people think marriage is becoming obsolete.

Chinese authorities recently arrested four men for digging up corpses and selling them to people desperate to arrange marriages: “ghost marriages” that would prevent the deceased from being lonely in the afterlife.

Out of concern for the welfare of family at home, American travelers annually purchase more than 150,000 insurance policies that provide coverage should they die in a plane crash. The policies are popular, even though the risk of a fatal airline crash is infinitesimally small: 45 million to 1.

During the holiday season, people in many parts of the world bring dead trees into their homes and place electric lights on them. The tradition is popular, even though the risk to the home and its inhabitants is significant; in the United States alone, enough trees catch fire to cause about $6 million in property damage annually.

So what are humans like? Hard to say, isn’t it?

In one situation, people seem caring. In another situation, they seem callous. In one culture, they are religious. In another, they are not. One social group values marriage, another finds it obsolete. In one role (traveler), people are cautious, and in another role (holiday decorator), tradition sweeps caution aside.

How, then, can we understand the psychology of human beings? We must study people as well as the situations, cultures, groups, and roles they inhabit. The perplexing diversity of human behavior can be comprehended only by studying the social world people inhabit and their beliefs about that world. This is the lesson of social psychology, as you will see in the chapter ahead. ![]()

WHEN IS THE last time you spent a day alone—

Social isolation is unnatural. The world of friends and neighbors, fellow students and coworkers, small groups and big crowds, social roles and responsibilities—

If you want to learn about psychology as a whole, social psychology is a great place to start. The social world contains most of “the drama” (Scheibe, 2000) of human life: people texting and shopping; gossiping and arguing; making friends and enemies; following rules and breaking them; falling in and out of love. It is where individuals become members of teams, clubs, schools, companies, religions, communities, and nations and develop a sense of who they are and what is meaningful in life. If psychologists in the rest of the field neglected social psychology, they wouldn’t know what people are doing with their lives. And knowing this is the first step in building a science of person, mind, and brain.

We begin with social psychology’s study of social behavior as it occurs in crowds, groups, and interpersonal relationships. We then turn to social cognition —people’s thoughts about the individuals with whom they interact. The chapter’s final two sections show how social cognition can be more deeply understood by studying (1) culture and (2) the brain.

How could human behavior be described? Surely only by showing the actions of a variety of humans, as they are all mixed up together. Not what one man is doing now, but the whole hurly-

— Wittgenstein (1967, p. 567)