12.4 Social Cognition and the Brain

The history of social psychology illustrates a theme of the book. The field has incorporated three levels of analysis:

Social psychologists first conducted research at a person level of analysis. They examined the behavior of people in social settings (e.g., in crowds, groups, and social roles).

The study of social cognition introduced a mind level of analysis. Researchers identified thinking processes underlying people’s attitudes and social behavior.

More recently, social psychologists have deepened their understanding by moving down to a brain level of analysis. In the rapidly growing field of social neuroscience, they explore biological systems in the brain that underlie social cognition and behavior (Cacioppo, Berntson, & Decety, 2012).

Researchers who study social cognition and the brain face two main challenges. One is figuring out how to study the brain. Technological advances help to meet this challenge. Researchers commonly use brain-

The other challenge involves social cognition itself. Different types of social cognition may activate different regions of the brain. To relate psychological experience to biological mechanisms, then, researchers cannot just study the brain. They first must distinguish among different types of social thinking. The following distinction has proven valuable (Van Overwalle, 2009):

Thinking about others’ ongoing psychological experiences: When thinking about others, you sometimes focus on their ongoing psychological experiences, especially their current goals and feelings. You ask yourself, in essence, “What are they trying to do?” and “How do they feel about it?” If, for example, you observe someone telling jokes at a party, you might ask yourself what the person is trying to accomplish by telling jokes, and how he or she feels if nobody laughs.

Thinking about others’ enduring personal characteristics: Other times, you focus on the stable, enduring characteristics of other individuals; you try, in essence, to figure out what kind of person you are observing. For example, returning to our joke-

teller at the party, you might ask yourself whether the individual is an extrovert (an enduring personality trait) or is intelligent (an enduring mental capability).

Brain research indicates that different parts of the brain are active during these two different types of thinking (Van Overwalle, 2009). So let’s consider them one at a time.

Thinking About Others’ Ongoing Experiences

Preview Question

Question

Why do we wince when we see other people in pain?

Why do we wince when we see other people in pain?

If you see someone being injured, you wince—

543

Research indicates that this is exactly what your brain is doing. When you observe someone else, your brain simulates the other person’s ongoing experiences (Gallese, Eagle, & Migone, 2007). It does this by automatically activating some of the same neural systems that are active in the other person’s brain. The brain regions that simulate other people’s activity are called a mirror system (Gallese et al., 2007; Rizzolatti et al., 2001; Van Overwalle, 2009) because they reflect the observed actions of others.

As also discussed in Chapter 7, the mirror system—

The mirror system helps organisms to not only imitate others, but also understand them. By simulating actions, the brain creates feelings in the observer that mimic those of the observed organism. This enables the observer to understand the ongoing experiences of the organism (monkey or person) being observed.

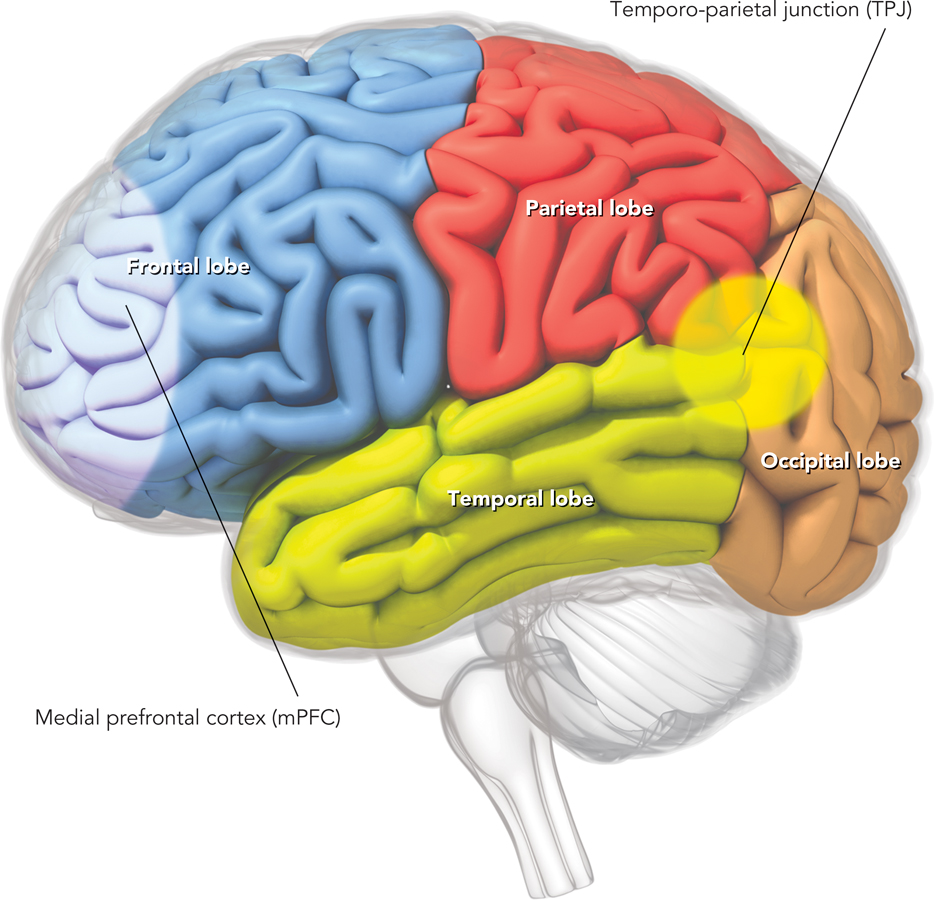

A meta-

Evidence of the TPJ’s role comes from studies in which participants think about other people’s behavior while the participants’ brains are scanned. The TPJ is not particularly active when participants consider the background characteristics of others, such as where they grew up or what job they have. But it is highly active when participants contemplate other people’s behavior. This is particularly true for unusual behavior (e.g., learning that a person has joined a cult) that prompts extra thinking about the other person’s thoughts and feelings (Saxe & Wexler, 2005).

544

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 16

One reason we are able to understand what others are feeling is that we have a uPlw4J7VMhQcp595 system in the brain that simulates their experiences. Hundreds of fMRI studies indicate that this system’s functioning occurs, at least in part, at the junction of two lobes in the brain: the PNFV1njeGXJwOgC6JZm0DA== lobe and the jr7rfAcCnJUVnH26e1XTrQ== lobe.

Thinking About Others’ Enduring Characteristics

Preview Question

Question

Is thinking about what people are experiencing different from thinking about what they are like?

Is thinking about what people are experiencing different from thinking about what they are like?

When people think about enduring characteristics of others—

The mPFC is highly interconnected with other brain regions. This may explain its role in judgments about people’s enduring traits. To make a trait judgment, you have to integrate different types of information. For instance, if you see someone acting in a friendly manner, you can’t conclude that “she’s a friendly person” until you first consider her behavior in a variety of situations, and relate it also to the level of friendliness displayed by other people. A highly interconnected brain system such as the mPFC is able to take part in this integrative judgment (Van Overwalle, 2009).

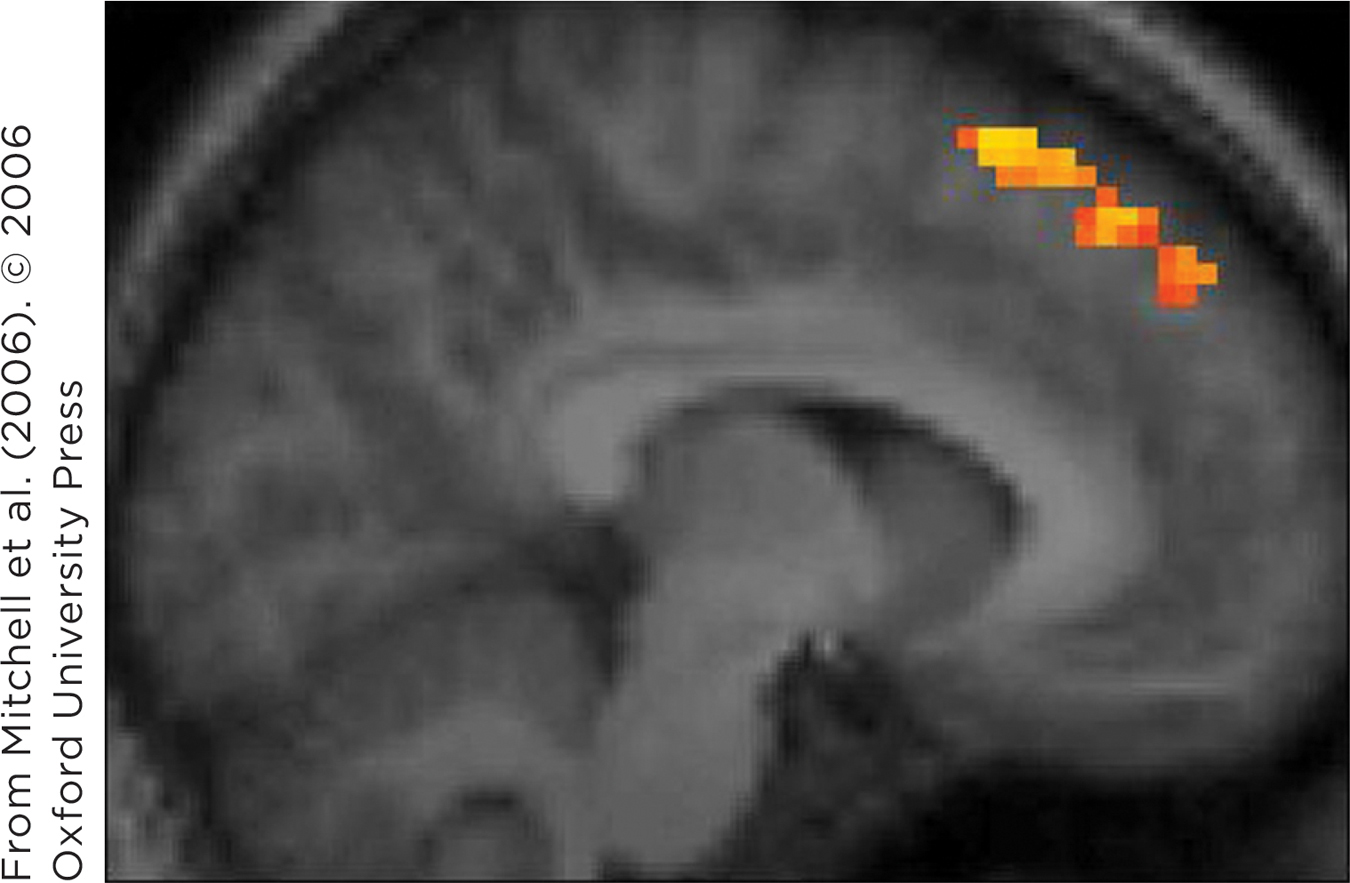

Evidence of the mPFC’s role in social cognition comes from research in which participants saw pictures of people that were accompanied by statements (e.g., “He watched TV all day instead of looking for a job”; Mitchell et al., 2006). On different trials, participants were asked (1) to form an impression of the person’s psychological characteristics or (2) to engage in a memory task in which they remembered the order in which statements appeared. The mPFC was particularly active during impression formation (Figure 12.10).

Note that the mPFC and the TPJ are very different regions of the brain. The differences in brain research correspond, then, to the psychological differences between these two aspects of social thinking: thinking about someone’s ongoing experiences or their enduring characteristics.

Research findings such as this display the rapid advances made in the field of social neuroscience. Not long ago, social psychologists never expected to be talking about the TPJ or the mPFC; theirs was a science of persons. Then—

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 17

- sXjQMkKXgSC4wroc44lJ00i30J61WLCIqUDUVeuALAFue/3qkA68aWy8psNiZx1OAMh5pxuoemtULGxKXaD0nW5N77QeUR5mR8bnHM8IeBEv+IglIq/dxwvoPT/C0zJKhmiDeztII72e79s7hQlzVQYnkYf4XAfP3K/gXObugbUcWMsNKgLUqpoE8oyOGK+eB3eluHZ5IHBjZWL9ETO7o6FeSoHdbTBSE/WWNF5Yq9VuqnIFaiuqg5ArFqKOaoxg6m57eu3jDuP3RlQmHRytA3D5p0rxcXhOw1XF2MDlG0jpfxBSMRPbxnxxuJnzmx5WmLyMd5QHjNgDcNNoHlJ4/SuA276KXjElJdIGUg==

- jtlTn5Up9bVPo2jmKFZWM5P/gPQWpAIvE7FLH5XOh+xtKsKt1cqhdtQ4VJfw4UTMkwwGMRdjwsZjFGWqiw5xer9YmBbIGqKcQuqAjzvM9gHWXPpCJNJxz59OPvpMtxYJSLbOh4vO8GadukoeAhai6FOXnDK7fWmnJLO+fOJgwAucb/0MCtQs5B+1c34KbhDD1RWqSKibtBQMvAtUir6v1ZL93nX4LgJL97RW9CSa6f1f59F3GH5kueseGaXwJ57A/zmtZtzDArWmkdSMRAOnxOdbjIyXlnAsIPpAVr96mbczxafoC88DMdsocAeiKWCvx+RrcvwCtWyCA1Tk

a. The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) is highly interconnected with other brain areas, thus enabling it to integrate lots of information. b. Yes, brain research confirms that different areas of the brain are active during these two tasks. Mirror neurons in the temporo-parietal junction (TPJ) are active when thinking about others’ ongoing experiences, whereas the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) is active when thinking about others’ enduring characteristics.

545