13.5 Trait Theory

Preview Question

Question

What characterizes the measurement of personality in trait theory?

What characterizes the measurement of personality in trait theory?

In personality psychology, a trait is a person’s typical style of behavior and emotion. (“Trait” contrasts with the concept of psychological state—

Trait theorists recognize that good measurement benefits not only basic science, but also practical applications. Suppose you are hiring people to fill jobs at a company and want a sociable salesperson, an honest accountant, and a manager with a calm leadership style. There will be many applicants. Which would be best for each job? To find out, you need good measurement tools: efficient and reliable measures of the traits of interest. This is exactly what trait theory provides.

By way of background, trait theory has a long history. Early in the twentieth century, psychologists recognized that measurement principles used in the study of intelligence (see Chapter 8) could be applied to personality. By asking people a large number of questions and scoring their responses, personality could be measured. In the latter half of the twentieth century, research on genes and individual differences indicated that variations in personality trait scores were, to a significant degree, based on inherited biology (see Chapter 4). By the century’s close, the combination of quantitative measures and genetic findings made trait psychology a major force in the science of personality.

Structure: Stable Individual Differences

Preview Questions

Question

What scientific method do trait theorists use to reduce the thousands of traits in our language into the Big Five (or Six)?

What scientific method do trait theorists use to reduce the thousands of traits in our language into the Big Five (or Six)?

What does Eysenck’s research suggest is the biological basis of the trait extraversion?

What does Eysenck’s research suggest is the biological basis of the trait extraversion?

The major structure in personality trait theory is—

Consistency: According to trait theory, personality traits express themselves consistently, across time and situations (Allport, 1937; Epstein, 1979). A person who is high in the trait conscientiousness, for example, would be expected to display conscientious behavior in a consistent manner (e.g., the person might be a reliable employee, a hardworking student, and a law-

abiding citizen). Individual differences: Personality traits refer to differences among people. Most trait psychologists try to identify a small number of traits that can be used to describe individual differences in any population of people.

On average: Traits refer to what people typically are like; in other words, what they are like on average. Suppose you are very friendly and pleasant with everyone except one particular person, whom you dislike. A trait measure of friendliness would average your behavior across all these relationships. Because you are friendly with most people, you would get a high score on friendliness. The score reflects your typical behavior.

572

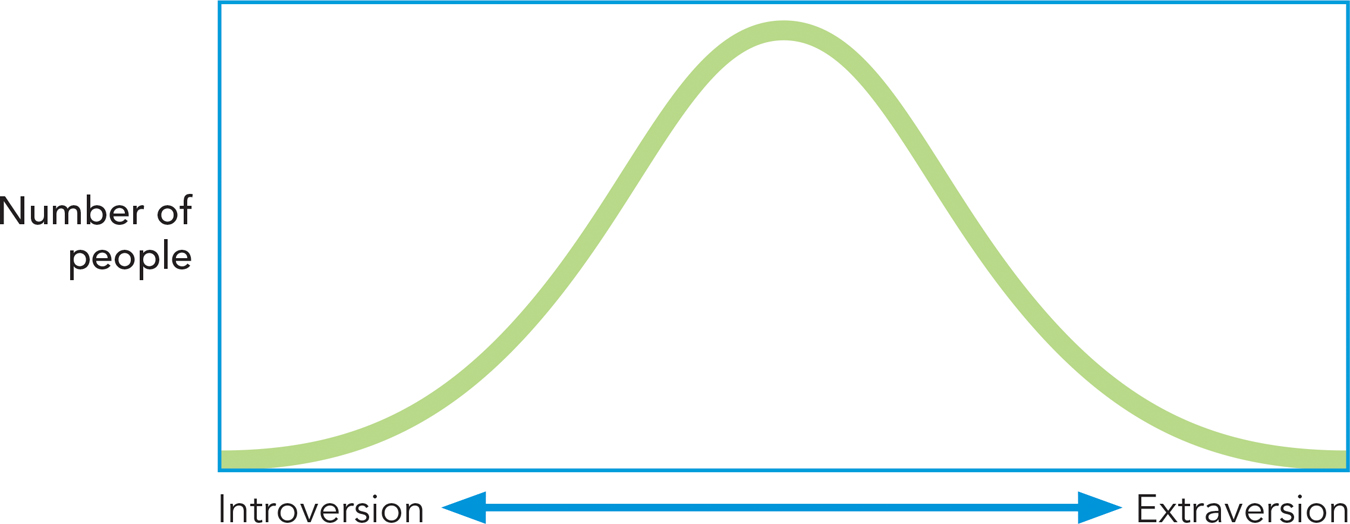

In addition to these three defining qualities, the word “trait” has two extra meanings to most trait theorists. One is that it refers to a dimension, not a category. This means that there are gradual variations in levels of the trait. In this way, personality traits are like physical traits such as height. Although we sometimes talk about “tall people” and “short people,” we know that these are not distinct categories of people; height varies along a dimension. Similarly, although we may talk about “agreeable people” and “disagreement,” the trait of agreeableness varies dimensionally. For any given trait dimension, most people are near the middle of the dimension, and small numbers of people are at the very high or low ends (Figure 13.4).

Second, theorists see traits as causes of behavior (McCrae & Costa, 1995, 1996). Again, an analogy with height is useful. If someone buys shirts with extra-

If an extraterrestrial were to come to Earth and ask, “What are the most important ways in which individuals differ from one another?” what would your answer be?

With the meaning of “trait” established, the next question to ask is what are the most important personality traits? There are two approaches to answering this question; we’ll look at both in the sections ahead. The first is to examine words in everyday language (Ashton & Lee, 2007; Goldberg, 1981). The lexical approach to trait theory presumes that people will notice, and invent words for, all significant differences among people, and thus that words in the language contain clues about the most significant personality traits. The other approach is to examine biology (Stelmack & Rammsayer, 2008). Neural or biochemical differences between people may produce variations in personality.

PERSONALITY TRAITS IN THE LANGUAGE. Imagine opening a dictionary and listing all the words that describe personality traits. You start with “abrasive,” move to “absent-

Incredibly, two personality psychologists once did just that: They listed every trait word in English—

The length of that list poses a problem: Measuring 4000 traits is impractical. It’s too much work to develop 4000 tests, and even if you did develop them, who would ever take them all? Trait theorists need to identify a small set of traits that correspond to the most significant individual differences in personality. They do so by using factor analysis.

Factor analysis is a statistical technique that identifies patterns in a large set of correlations (correlations are described in Chapter 2). Suppose you measure numerous personality characteristics—

573

Now suppose you want to know how, in general, the traits correlated with one another. You suddenly are faced with a lot of numbers: If 10 traits were measured, there are 45 pairs of traits and thus 45 correlations. If 100 traits are measured, there are 4950 correlations—

In the study of personality traits, factor analysis usually yields a simple result. Only five or six traits are needed to describe the main individual differences in personality. One group of five traits is found so commonly that it is called the “Big Five” (Goldberg, 1993; John, Naumann, & Soto, 2008). The Big Five personality traits are found consistently when people’s descriptions of personality are analyzed with factor analysis. The same five traits are found when analyzing people’s descriptions of their own personality and people’s descriptions of others’ personalities (e.g., close friends or one’s spouse; McCrae & Costa, 1987). The Big Five traits—

13.4

| The Big Five Traits | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Big Five Trait |

Definition |

Characteristics |

|

Extraversion |

A tendency to approach the social and material world in an energetic manner |

Sociable, active, assertive |

|

Agreeableness |

An orientation toward positive, prosocial feelings and behaviors when interacting with others |

Altruistic, trusting, modest |

|

Conscientiousness |

A tendency to control inappropriate emotions and impulses and to follow social rules |

Reliable, hardworking, organized |

|

Neuroticism |

A tendency to experience negative emotions |

Anxious, nervous, sad |

|

Openness to experience |

An orientation toward a complex mental and behavioral life, and a diversity of experiences |

Creative, artistic, liberal |

|

Research from John, Naumann, & Soto (2008) |

||

The Big Five can be assessed easily. Table 13.5 contains a simple 10-

In this measure of the Big Five trait variables, two items tap each of the factors: Extraversion (1, 6*), Agreeableness (2*, 7); Conscientiousness (3, 8*), Emotional Stability (4*, 9), and Openness to Experiences: (5, 10*). The asterisk indicates that the item is scored in reverse; strongly agreeing with the item gives one a lower score on the trait.

13.5

| A Simple Big Five Measure | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Disagree strongly |

Disagree moderately |

Disagree a little |

Neither agree nor disagree |

Agree a little |

Agree moderately |

Agree strongly |

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

I see myself as: |

|||||||

|

1. _____ Extraverted, enthusiastic 2. _____ Critical, quarrelsome 3. _____ Dependable, self- 4. _____ Anxious, easily upset 5. _____ Open to new experiences, complex |

6. _____ Reserved, quiet 7. _____ Sympathetic, warm 8. _____ Disorganized, careless 9. _____ Calm, emotionally stable 10. Conventional, uncreative |

||||||

|

Reprinted from Journal of Research in Personality, 37: 504– |

|||||||

Some trait theorists think that the Big Five trait model is missing something—

THINK ABOUT IT

Do you think that everyone has the same five traits? Or might you have some distinctive personality traits that make you unique, yet that are not represented within the Big Five approach?

574

In sum, the lexical approach summarizes personality traits found in everyday language. The big question, though, is whether that is good enough. Ultimately, psychologists don’t just want to know about the language of personality; they want to know the “flesh-

575

THIS JUST IN

Traits as Networks

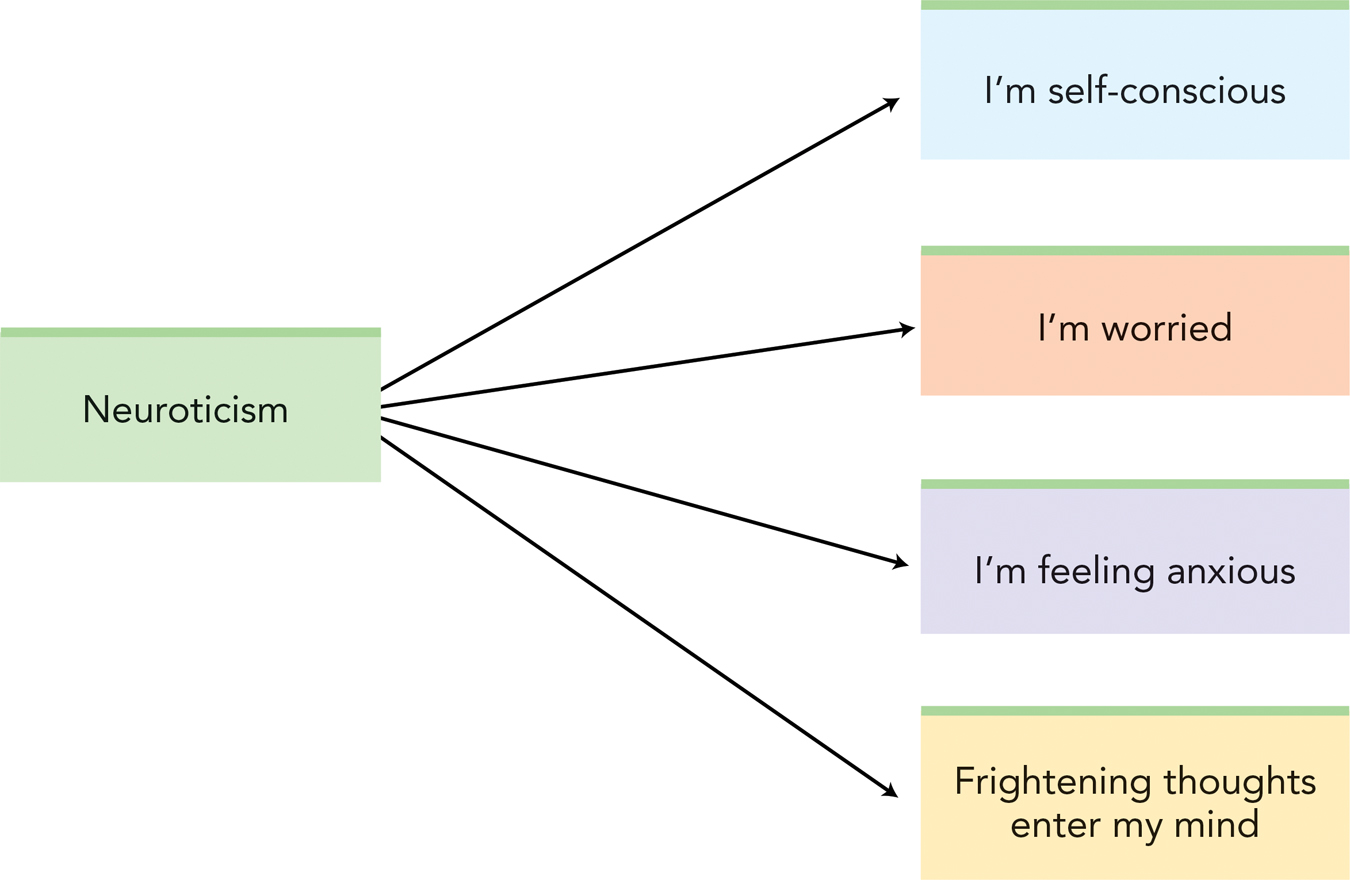

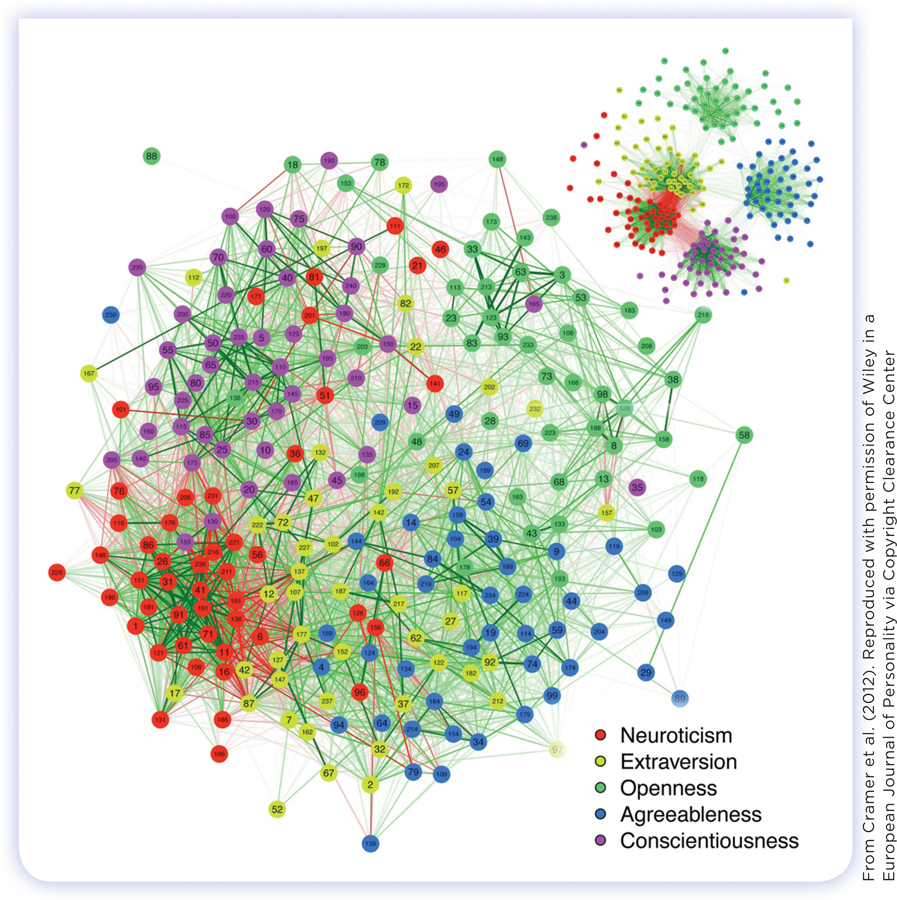

When researchers give people personality tests, groups of test items correlate with one another. For example, people who say that they are (1) self-

The cause, according to trait theory, is the influence of traits. In our example, the trait of neuroticism is said to cause the items to correlate with one another (Figure 13.5).

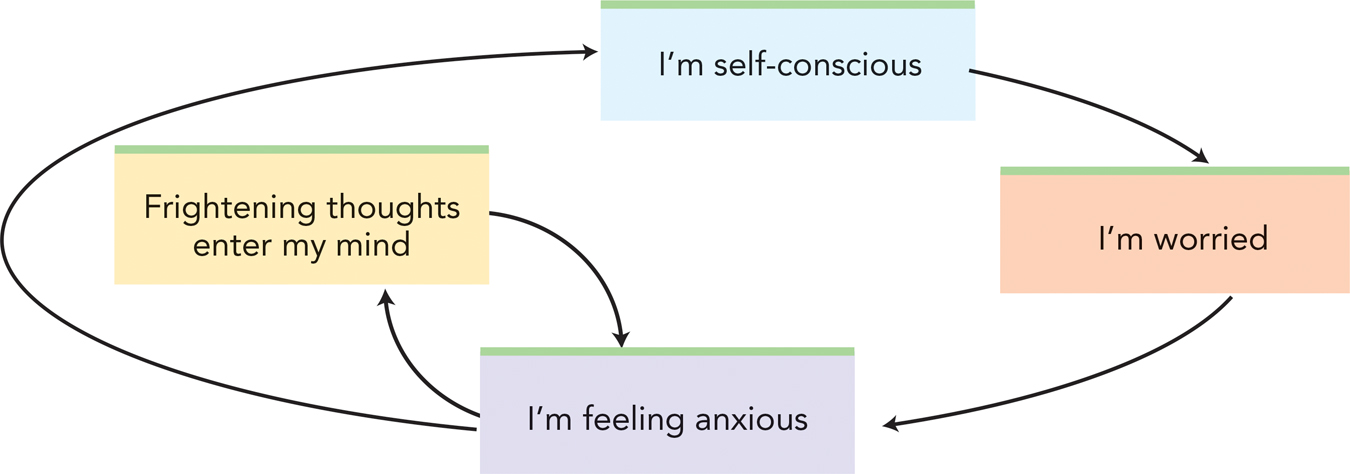

Although trait psychologists believe this, there are other ways of thinking about it. A research team in the Netherlands recently developed an alternative conception: not traits as causes of behavior, but traits as descriptions of “networks” of thoughts and actions (Cramer et al., 2012). In this view, networks arise because the psychological qualities measured by test items causally influence each other (Figure 13.6). Consider the four qualities we just mentioned. Self-

Researchers use a statistical technique called network analysis to depict the relations among individual test items. The technique is complex, but the idea behind it is simple. Instead of adding up test items to give people a single score, network analysis analyzes the items one by one. A network graph depicts the ways in which items are linked (i.e., correlated with one another). As you can see in Figure 13.7, when researchers analyze personality test items this way, they find overlapping clusters of items that roughly correspond to the Big Five traits (Cramer et al., 2012). The findings are consistent with the theoretical analysis in Figure 13.7—

576

Why is network analysis so important? There’s a critical difference between Figures 13.6 and 13.7: In Figure 13.7, there is no single “neuroticism” variable. In the network analysis, neuroticism is not a real “thing”—that is, not a structure in the mind that causes consistent patterns of behavior. Neuroticism is merely a term that describes networks of thoughts, feelings, and actions that go together inevitably. The same holds true for the other Big Five traits as well; each is reconceptualized as a description of networks of experiences and actions, rather than as a psychological structure that causes behavior.

The picture reveals something interesting. Items measuring the Big Five traits do not fall into five separate clumps; they do not appear as five distinct traits. Rather, items representing the supposedly different traits are intertwined. Network analysis thus suggests that personality structure consists not of five separate, discrete traits, but of an interconnected system of thoughts, feelings, and actions.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 17

True or False?

- /1demM1xIlY6ceiyMvdZG3vCbaQTJ1FO9BfTBy4P2w2S7/vQ5edXdLgDLGdKVULO0yAdAdJyJ1TiQUBFSsCulFeBh6o1yYBkhqe5FT93WPTtWSeW72TpE6HxpukBtvMe3ph3BJPlf7JeXiZUKNRvb5viXwowPBYwJ5JhCB8q171s3qCLE/qW7HjsZa9pDbqdcjG25EdwVvJ4z9GGysKQPdPPpoOwrl5yboCfEQbcd541NeExlz/GWg==

- B+JCGGOn5+Jsfqw7Sgz204/h1Bmh5hn7gFxDY7X9EC5bqzqeq5BZoWxeWW4XWDunilVnX7Q8E/LVYB2pfAgiTNKfS0Ud6Fy8Y046i5qGyVwA1wWyILqyBxHvrWuggIV4L5JKXl4p0OWBOgLtYTtNTZvL7w1i5bOK+gE0HPKttnm6XCEmdX1fja1qWRdnVFjjWxR43Csn69TPQpYJzZMkrZEESPRxPjof0a5ypgcF9M3+q9vZMFVUdpgiHBI=

- 4YweVEaI98OYGkPcOvqP82RlbkeH9j+qGMbiJLki7dM8r4mVqdJyLBb41tZTuQx6DcD7Uw9+BCSWPqU1DuOxQ3jKhPi4o8IUdrSANtY90t0gPEMhDMrdKaY56HjbPTICegAhAlU1voqTt7I76lO33FpxQtPm59hqHKVvRupB0usEWMrZ24Dh6VDvlCy0wOi0ImaSdTpXX03yK6WD4sYWes9jrXhC3WOSkSZDO5JRQb+RYWIVFwSc4W52pq8vaHpFNnu6kPTau+ugbMnkgFyYzYPYaik=

PERSONALITY TRAITS IN THE NERVOUS SYSTEM. People differ biologically in many ways (height, weight, blood pressure, bone density, etc.). Might some of the biological differences produce individual differences in personality traits? Many trait psychologists have pursued this possibility (Stelmack & Rammsayer, 2008). One of the first was the British psychologist Hans Eysenck.

577

Eysenck (1970) searched for the biological basis of extraversion. He hypothesized that extraverts (high-

Some evidence supports Eysenck’s idea. In electroencephalographic (EEG) research (see Chapter 2), investigators record the brain activity of introverts and extraverts while presenting simple stimuli, such as flashes of light or moderately loud noises. Just as Eysenck predicted, the brains of introverts react more strongly than those of extraverts to this physical stimulation (Stelmack & Rammsayer, 2008). Outside of the lab, in everyday life, the differences in brain reactivity may create differences in introverted versus extraverted behavior.

Eysenck also sought the biological basis of neuroticism, that is, the tendency to feel anxious and worried. Here, he predicted that individual differences in neuroticism would be linked to variations in the reactivity of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which responds to environmental threats (see Chapter 3). People with high scores on neuroticism should have “jumpy” nervous systems. This prediction, however, has received less support (Stelmack & Rammsayer, 2008). Individual differences in self-

One alternative was advanced by the British psychologist Jeffrey Gray and his colleagues (Corr, 2004; Gray & McNaughton, 2000; Pickering & Corr, 2008). Gray identified a problem in Eysenck’s theory of neuroticism: It failed to distinguish between two fundamentally different emotions, namely, fear and anxiety. In Gray’s theory of personality and motivation, different brain systems are said to underlie these different emotional responses.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 18

Trait refers to the major ways in which people FTIZvvOu0bD4DF0c from each other in their average tendencies. They are Lwhn5mjnw4BqUErfLh9fKw== versus categorical and are said to be the jkZ5Ck7Br6hwyF2P of behavior. The statistical tool of sFwrC8RjfSlDvXjPDhnBcKItMn0= is used to identify the major individual differences in personality. Hans Eysenck hypothesized that differences between introverts and extraverts could be tied to differences in K2vS8WozSwB6aSVArSeD0g== arousal. His hypothesis that differences in neuroticism could be tied to differences in reactivity of the zPifQ5brCURiYGiU6ARqUA== nervous system has received little support.

Process: From Traits to Behavior

Preview Question

Question

How can Eysenck’s work link structures to processes in trait theory?

How can Eysenck’s work link structures to processes in trait theory?

Traits are the personality structures of trait theory. What about personality processes?

Trait theorists have devoted less attention to dynamically shifting personality processes than to stable personality structures (Hampson, 2012; McCrae & Costa, 1996). The lexical approach to personality traits, for example, analyzes personality structure exclusively.

578

Biological research, however, does shed light on personality processes. Consider again the work of Eysenck. His analysis of cortical arousal and extraversion identifies brain processes that come into play as people encounter situations featuring low and high levels of stimulation. Other researchers have extended Eysenck’s analyses by showing how extraversion may be linked to bodily arousal, which, in turn, affects thinking processes (Humphreys & Revelle, 1984). Nonetheless, the analysis of personality processes is not the strong point of trait theories.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 19

Research that links extraversion to bodily 95PO9DVPejW0k3sk is a promising way for trait theorists to link structure to 3pX8UQIUx3G8sPc1.

Assessment: Measuring Individual Differences

Preview Question

Question

How do trait theorists assess personality and what outcomes can be predicted by these assessments?

How do trait theorists assess personality and what outcomes can be predicted by these assessments?

We’ve seen that analysis of personality processes is not a strength of trait theory. Personality assessment, however, is. Trait theorists have developed tests that reliably measure individual differences in personality traits.

COMPREHENSIVE SELF-

The NEO-

The NEO includes about 50 test items that measure each of the five traits. Why so many? No one question can measure a broad personality trait. But a large set of questions can. For example, conscientiousness (see Table 13.4) test items ask about keeping one’s possessions in neat order, paying bills on time, working efficiently, finishing jobs, and so on. Adding together responses across the items provides an accurate measure of the trait.

As noted earlier, there are shorter tests (Gosling, Rentfrow, & Swann, 2003; Rammstedt & John, 2007). Brevity sacrifices accuracy, however. When psychologists want highly accurate measures of Big Five traits, they prefer to use longer tests, such as the NEO.

PREDICTING BEHAVIOR. Do these personality tests predict people’s behavior? Often they do. Let’s see two examples, the first of which involves personality and personal space.

Most people have one or two personal spaces, that is, areas they decorate themselves. In your bedroom, for instance, you might arrange the furniture and choose art for the walls. Personality predicts decoration preferences. Researchers sent participants to individuals’ office spaces and bedrooms and asked them to judge the personality traits of the inhabitants. They made the judgments without ever meeting the occupants. Separately, the inhabitants of the rooms completed questionnaires measuring their personality traits. The ratings of conscientiousness, extraversion, and openness to experience that participants gave to occupants based on their rooms correlated significantly with the occupants’ self-

579

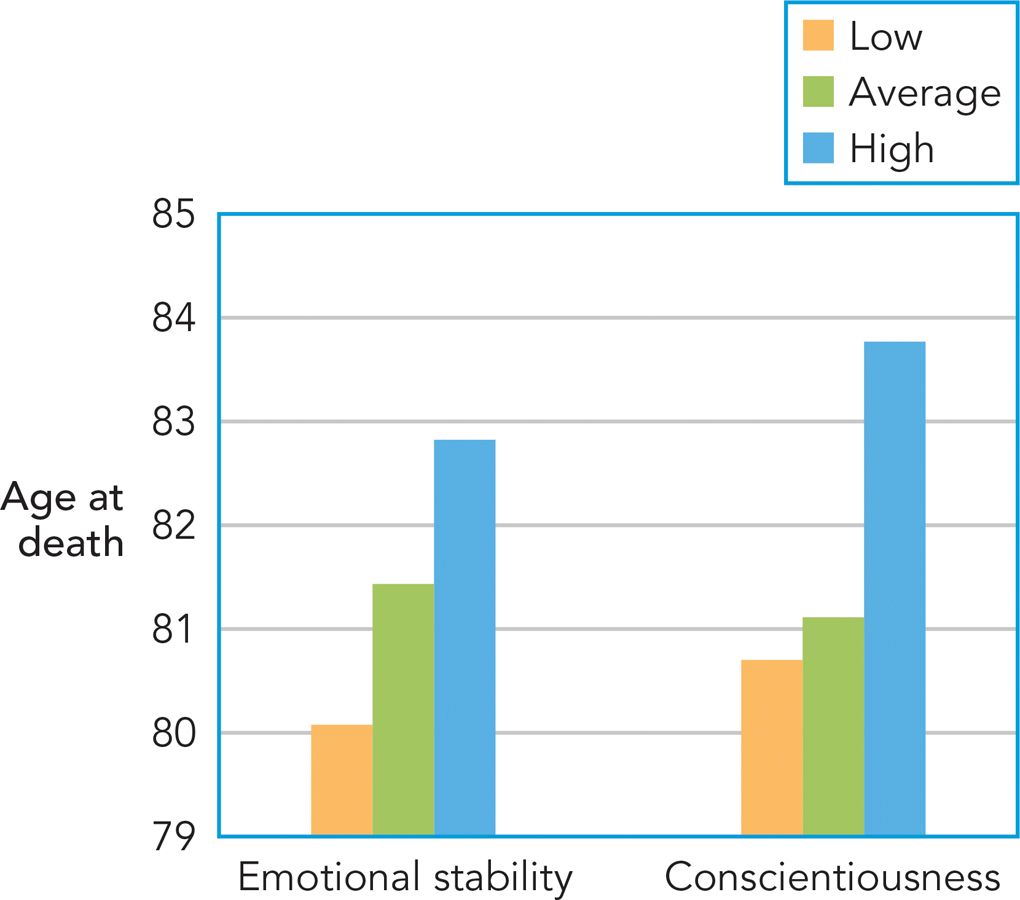

Personality traits also predict a more serious outcome: mortality. Researchers (Terracciano et al., 2008) measured personality traits in a large group of adults, and then followed their life course over decades. During this time, some research participants died. Remarkably, personality traits predicted length of life (Figure 13.8). People with more emotionally stable (low neuroticism) personalities, and those with higher levels of conscientiousness, lived longer (Terracciano et al., 2008).

Why would personality predict mortality? People with more emotional personalities may experience more life stress, which can impair health (Chapter 10). More conscientious people may maintain healthier lifestyles and have regular medical check-

THINK ABOUT IT

Conscientiousness predicts the neatness and organization of people’s living spaces. Does this mean that the trait of conscientiousness causally affects people’s behavior? Or might it be the opposite: Behavior affects self-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 20

True or False?

- RWMeTZYl0MXJMEsQ7Haq9NvQThgwd/vpClRsfE2zEc2FjmfwbfWrY3Yf4Tjw3zDvHvgv2xBev/mW+GeeyCRsXtqVWFVtRImpJyU0fG7CBywk2xmO6LOLUjxec0qD0/HCcGPK8+KcEqePLp+pjRgIvo/rm1Hecpbiezzu1ddxT8AD9hWSGD2IEvckW5s=

- USlRO7Vw8WmDlRTbUgOfjBTxDcgAkIJFBU1scZsFAkXA4sP1BBfBmicBjYJ8XEpMd5CEHFuq38SXwkFUHdoqbRhdLn00zuPeow/sb/7dIdDwKONLV3Tnu/Q/vXJv5JnucLaQSLF/kOjis53ltu/20WW0Z6dZt47txY5FdYU4WrB2jYNqlucSLQUuntbFi03TwPo2UShXnVRlf17+bjNtzjiKpj4APrb/QkqF7Jn39vBGqCBkYjIj66OHpFuRW0YttddBD6AhKZT7w79suwyX+PmEB0bSAhiaVuvEFkRF6Mva8jSr

- B5bU+Yr8YjdJhABpR/ZnUf1P9ulOfP/00YJeULq7n6vvXi09EUrzOmDtQLSb/NMyyhPHacPSyxSGs/ulBGlFhZ66qbNIKDerwzzlFmaixiD7DT7UpFlR1AWemBrCACPwgX9F0qKoiVU9Fald4wgvgD6CizhuywRO

Evaluation

Preview Question

Question

What are some strengths and weaknesses of trait theory?

What are some strengths and weaknesses of trait theory?

Trait theories have three major strengths. They provide simple methods for assessing individual differences. They have spurred research into the connection between personality traits and biology. Their use of sophisticated statistical techniques brings scientific rigor that was sometimes lacking in prior theories of personality.

However, trait theories have limitations, too. One is that, like Rogers’s humanistic theory, they are insufficiently comprehensive. As we’ve noted, trait theory says little about personality processes—

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 21

Which of the following statements about the strengths and weaknesses of trait theories are true?

- zogNSW9SFf0y/x3yh5mtby4HE1djT1AsRfLPnRQDIkuO4txnW51vYpxAI/u8Yu7yAWcEJNdU2de43b5C+QDyTCkNKE/08C0uTeZYE2hICCWICzqklRfGeWpj8flsSOu3N99jC+vA2Fhm/oFwTRYeDeYzvUda6qPO6dOjhpoZ0uYJrREs0dv94A==

- y2QskcTp+IPKtopRFbP6gS7kxwHg/ox5jQbGwFOoGwL09A13tFedeLydbnaFaMj2laU1H1eMNLSgAqiwMpLzvzGHtTqZaWVbT9kD82WPlCF4MyllOM57NZnordEGiGmrlDLPHJqfsU7VJnZvKY37IAvZbwB8gpaMQM/spYTfb95ixU6l

- GYbYOLKgjcvF54l5h9GQMsqyb5n18tO7mkgpACxqZY2zI+hEqFlac1+wQpQeAFE2fiarhpHw+8UL2l06SnWR6++y488GmaVS/UrvgTvc31R9V/mOmEPH3GykFFU4dHpQE+jiaGqGCKDCOJe/N4RuK3Op9aYDVcijOQnef0H+Py4o3Y6CELaGeqSOGfXHdFeLsvOyN8auUxqazddX4XeECMx4DekZVjdXLUqBUeJVQCvUB6rSbIevVqNz/8zaviuzWHJLst08hknwcHsiljL1zvzfbZ8ZyGl5

- cOVEeEB1WPOmotYFYdWENA2tlAwxM4KScdz4qlNlamX2nH9h1Hi413TsyU9S1SgOmfyASwZpdcNitQ45Xqdr6Ngg95rMRua5DaWT3gAzxwRFunVtebngCQjAXCwgKnypEyLShkCLZu2RtT3TTLVeITKWsgIGFQHSiTGUVJ+BsgkEyWbiiuh1rg3zc91bschkGWSvsqpwp9QjdoYzS4IzDSNMha+NkdOTgcSoxFHcAu7+cksXypHUkWHBL5tO6jOnxZi3rYEBrRs=

- qfehEF4DIWJUxvciK/Cnn4WOJvPWjVytv8yco1YCFmiK5fjt9jjIf3VIRoajwDFGYEO04+XD6TKh608m+wtSkPHopDIW0F4ezWucVeTKeWw2ZhHcewVS9QKbiZP063gaKoi08u40OXGqLdsDwhc652pCBhCGEUTnu+39Ep9DlnVnRwQ/RQMnHZyZ6Mw=