13.6 Social-Cognitive Theory

Preview Question

Question

What did social-cognitive theory’s two most prominent theorists—Bandura and Mischel—emphasize in their conceptualization of personality?

What did social-cognitive theory’s two most prominent theorists—Bandura and Mischel—emphasize in their conceptualization of personality?

The fourth of our personality theories is social-cognitive theory, an approach to personality that emphasizes the social experiences through which people acquire knowledge, skills, and beliefs about themselves. According to social-cognitive theory, these cognitions—one’s knowledge, skills, and beliefs—explain an individual’s distinctive patterns of emotion and behavior.

Social-cognitive theory differs from the other three theories you’ve learned about in both substance and style. In substance, it attends more carefully to social context. Social-cognitive theorists examine the way personality develops and reveals itself as people interact with others in the social world (Shoda, Cervone, & Downey, 2007). In style, social-cognitive theory is integrative. Theorists have built a personality theory by drawing on research findings from throughout psychological science (Cervone & Mischel, 2002). The advantages of this style of theory building may seem obvious, yet it’s not what the other personality theorists were doing. Psychodynamic, humanistic, and trait theories were relatively isolated from advances in psychology as a whole; Freud, for example, was famously uninterested in experimental evidence in psychology.

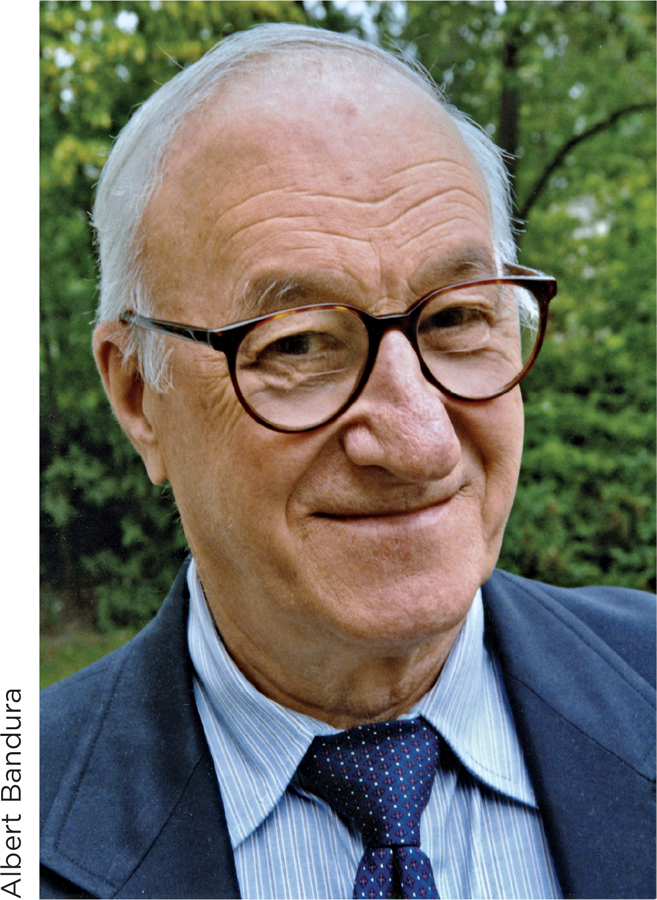

Albert Bandura, whose theory of personality explains the social foundations of people’s beliefs, skills, and experiences.

Many psychologists have contributed to the social-cognitive approach (see Cervone & Shoda, 1999). Two, however, stand out: Albert Bandura and Walter Mischel.

Albert Bandura’s social-cognitive theory of personality (1986, 1999, 2001) has two emphases. The first is personality’s social foundations. Bandura recognizes that, were it not for our experiences in a social world, we would not have the personalities we do. Our social skills, personal beliefs, and life goals arise through interaction with the social world. The other emphasis is personal agency, which refers to people’s capacity to influence their own life outcomes. By setting goals and developing new skills, people can guide the course of their own development.

Early in his career, Bandura worked with families of children who were highly aggressive (Bandura & Walters, 1959, 1963). Interviews with the children and their parents raised questions about how people learn to behave aggressively that Bandura then addressed in laboratory research. Throughout his long career, Bandura maintained this pattern, conducting basic laboratory research on personality processes while simultaneously addressing problems of great social significance.

Walter Mischel’s social-cognitive approach views personality as a system. A system is anything made up of a large number of parts that influence one another. The view that personality is a system contrasts with, for example, the trait approach you learned about earlier. In trait theory, personality was viewed as a collection of structures (the traits) that were independent of one another; there was little analysis of how one trait influenced another. But in his social-cognitive systems approach, Mischel focuses on interactions among the parts of personality. Those parts include thoughts (or cognitions) as well as feelings (or affects); personality is thus a cognitive–affective system (Mischel, 2004, 2009; Mischel & Shoda, 1995). A person’s distinctive pattern of interconnected thoughts and emotional reactions is the core of his or her personality structure. Regarding personality dynamics, Mischel emphasizes subjective meaning, that is, the processes through which people figure out, or assign meaning to, the events of their lives (Mischel, 1968; Orom & Cervone, 2009).

Walter Mischel, whose research has shown how personality is revealed in the way that people adapt their behavior to varying social contexts.

Mischel (1968, 2009) also is a critic of personality theories. He argues that trait theorists’ decision to study what people are like “on average”—their average level of neuroticism or conscientiousness—is costly. It sacrifices too much information about personality. Much of what is interesting about personality is the way an individual varies around his or her average: conscientious at work but not at home; confident with some people but anxious with others. To Mischel, this variability in thought and action, which arises as people confront the diverse challenges and opportunities of life, is key to personality.

It might be worth attending to the patterns of variability. … Although conspicuously absent in most personality psychology, such patterns are portrayed in virtually every character study in literature, revealing as they unfold the protagonists’ underlying motivations and character structures, and making them come alive.

— Walter Mischel (2004, p. 6)

Bandura’s and Mischel’s contributions complement one another. In combination, they form the foundation of a social-cognitive approach to personality that is furthered by many contemporary personality psychologists (Cervone & Shoda, 1999).

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question

22

Which of the following quotes are likely to have been uttered by a social-cognitive theorist such as Albert Bandura or Walter Mischel?

- YmJzRs09HUgztHpgrozsHv/QAv7ijMyVNgL5+z3hIh5ikbtLlHwla8U4i2fU4rhSWBU7SFyBST1vD/K4PEA/ZwP+51cwH5XybAxr7Af8nR2Vluchs87NVw8txg33vajO5DQSHKNAlS1CldnEvS2VFCDZvyHVS/pJn6wwnbdMjyo=

- oSIpduZx2p+ZsEIKsYkqHTX2xBml/3MVFiiEsE+Lfp/THAseNljuRIJqpGdHrQPN8YAshpPxJ2UcA11r83T3csSrmj6SP+rbj29wgpOelstnjzVVB2GQxl9phfRSdJMLj/mwcZHHEtkiX1PjmME88Kz6mT7u/HoO4508iZ7dLsq63rIaUTIhIy2QsrIRFH0pCvqODA3Z4SLPFgjn+8NpI1Vc9CoM8ymnEZYMdw==

- ZkUirT7JhbEL1jLDo6bwM9Qb6Skqdk8p9la4e4xybj1Am5VWfzMG6H4jWJlOkOPVx6hGQR9NTpu0mn26JxiUSiWpGrfQ3Bh5Z6nDld8/v5/8WOb/aAnwi7jLyXsVN4H9CL9wED4BeNYf3/I5EsEV2IDwdfJfp6qhpuoCPMfJGDFhS/p/IZeBLWWPCD/joQu6/ZJwj7RrhSQ=

- 2v1nzW1Ab/dyCcne9mm2NlWfAArBcpv/Vv9NjV1b4wR8+nW/hHRUZTn8srRxNf2ifXmGftMztUQETBcTQXD7hYcrtagNnXV7laYNP1/hM9wQACNuHi2m4/gEJ6fTQFQYnvmwGxD6KDkb/9aNpS/C4yuCJPwzpsZibo7Q6eTQbwUQiYQm0vjDj+6NzM51C+plzFBOhg==

- me9EcyU+K7glio8yFCW5BfCAxzFxRc4tUMPbzmuNdUR2Wxvazp/IrwNKN71Ec3jWOhq3VoaZ83KD/0T7/Ug/qKFZPFcVLddlW/ISlu7fYSK5+IzIhPIMK1VMGSMJIHbA9mwFpQHiiFGKYtbSHstLT9Ak3TRzNecj278dWzQpjEc=

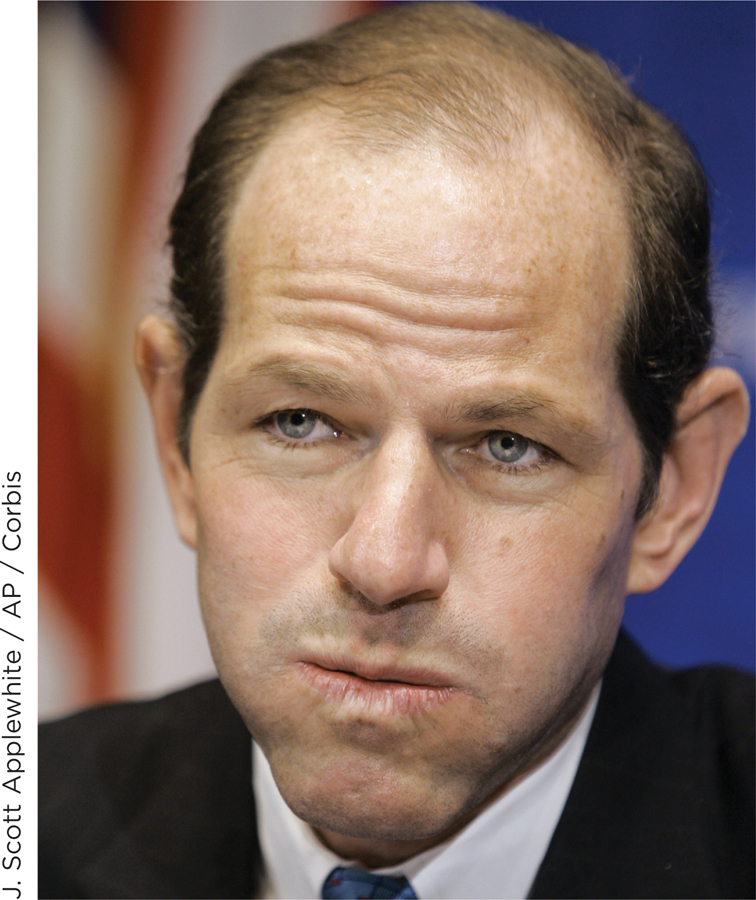

Personality inconsistencies According to social-cognitive theory, inconsistencies in behavior are revealing of personality. Consider the case of Eliot Spitzer: Leader of student government in college. Graduate of Harvard Law School. As a district attorney, he fought organized crime. As attorney general of the State of New York, he continued to battle white collar crime. He was elected governor of New York in a landslide and pledged to restore confidence in government (Gershman, 2006). Spitzer seemed to be a model citizen and leader, high on traits such as reliability, conscientiousness, and trustworthiness—until a prostitution scandal forced him to resign from office.

Structure: Socially Acquired Cognition

Preview Question

Question

What defines each of the three different types of personality structures within social-cognitive theory: self-referent cognition, skills, and affective systems?

What defines each of the three different types of personality structures within social-cognitive theory: self-referent cognition, skills, and affective systems?

Social-cognitive theory identifies three types of personality structures: (1) thoughts about the self, or self-referent cognition; (2) skills; and (3) affective systems. They are all personality structures in that they are enduring elements of the mind that contribute to people’s distinctive and consistent styles of behavior.

SELF-REFERENT COGNITION. Much of our thinking concerns ourselves. When starting a new job, you think not only about the job, but also about yourself: “Will I be able to handle the work?” When choosing a major in college, you think not only about the courses to take, but also about yourself: “Does this major really help me accomplish my aims in life?” These thoughts about oneself are called self-referent cognitions (or, equivalently, self-reflective thought). Social-cognitive theory claims that self-referent cognitions directly affect emotion and behavior (Bandura, 1986). If you doubt that you can handle the job, you become anxious at work. The cause is not a “trait of anxiety,” but rather your thoughts about yourself. If you think the major isn’t for you, you may become unmotivated in classes. The cause is not a “trait of low motivation,” but, again, your self-referent cognition.

Social-cognitive theorists distinguish among three types of self-referent cognition: beliefs, goals, and standards. Beliefs are ideas that we think are true. Self-referent beliefs, then, are ideas about yourself that you think are true. You may believe that you’re attractive, smart, or clumsy. Or hardworking, independent, or shy. Beliefs are key to personality because they shape people’s flow of thinking and of behavior. People who believe they’re so shy that they will embarrass themselves at big social gatherings worry about parties and tend to avoid them. People who believe they’re smart and resourceful feel confident in themselves and take on difficult challenges.

Bandura places particular emphasis on self-efficacy beliefs, which are judgments about one’s own capabilities for performance. “I’m confident I can get an A in calculus”; “I just can’t get myself to stop overeating”; and “When I have to speak in front of a group, I can’t control my anxiety” are all self-efficacy beliefs. Self-efficacy beliefs critically benefit human achievement. People attempt difficult tasks and persist when the going gets rough if they have a strong belief in their self-efficacy—their ability to succeed (Bandura, 1997).

Goals are thoughts about what we hope to achieve in the future. Goals are important to personality due to their power to organize and direct people’s actions over long periods of time (Little, Salmela-Aro, & Phillips, 2007; Pervin, 1989). Whether you’re exercising to look better and be healthier in the future, studying to do well on upcoming exams, or working at two part-time jobs in order to pay tuition next semester, your goals (health, good grades, remaining in school) are guiding your current behavior (the exercising, studying, or working).

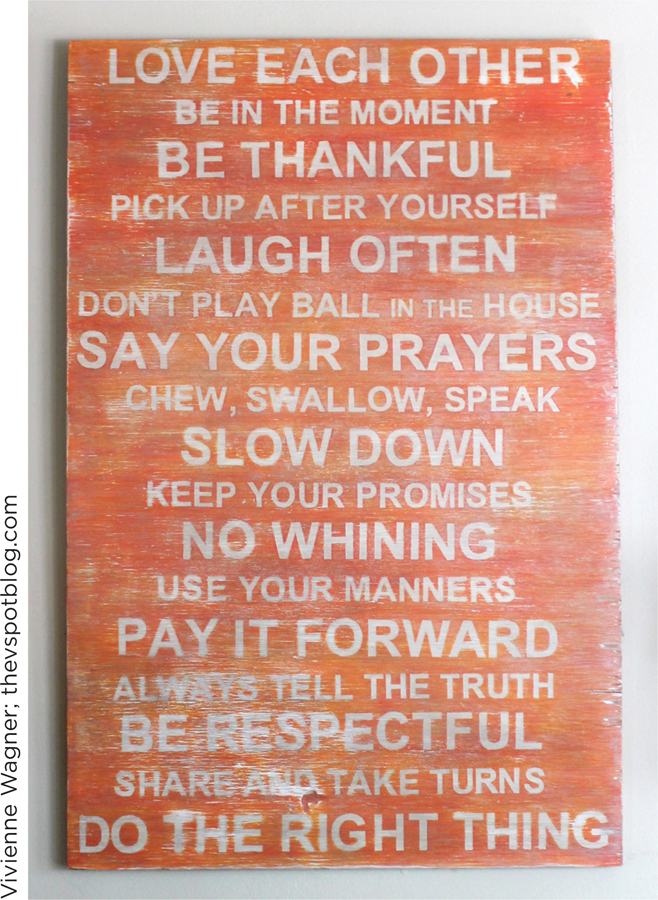

Do this. Don’t do that. Society surrounds us with guidelines for behavior. If we learn and follow them, they become personal standards—internal guides for behavior that, according to social-cognitive theory, are enduring features of our personalities.

Standards are ideas about types of behavior that are acceptable or unacceptable. Our personal standards are the criteria we use to evaluate how we’re doing. Statements such as “Ugh, that sentence I just wrote for the term paper was terrible” or “Uh oh, I look really fat” indicate that people are evaluating behavior according to internalized standards that prescribe types of behavior that are acceptable and unacceptable. The way people feel about themselves—proud, disappointed, elated, disgusted—is often determined by the standard they use to evaluate their achievements (Bandura, 1986). People with high, perfectionistic standards frequently are highly motivated (Bandura, 1978; Carver & Scheier, 1998), yet also prone to becoming depressed when they don’t meet their own standards of excellence (Hewitt & Flett, 1991).

Standards, in social-cognitive theory, play a role similar to the superego in psychodynamic theory. In both cases, the personality structure represents criteria for evaluating whether behavior is socially acceptable. Yet the theories differ. Social-cognitive theory takes a more flexible view of personality than does psychoanalysis. In psychoanalysis, the superego is said to develop early in life, through interactions with parents, and to be fixed after that. Social-cognitive theory, by comparison, recognizes that personal standards may change throughout life. If, at any point in life, people’s life circumstances change—they move to a new country, join a new religion, or experience some other major life change—their personal standards may change, too.

SKILLS. Sometimes the cause of behavior is not people’s thoughts about themselves, but another aspect of personality: skills (or lack thereof). Skills are abilities that develop through experience. Although you might think of skills in connection with activities such as jobs or sports, they also are relevant to personality. Some social situations—such as diffusing an argument among friends or having a good time at a party where you don’t know other people—require substantial interpersonal skills. Individual differences in behavior in those situations are caused by individual differences in the skills people possess (Wright & Mischel, 1987).

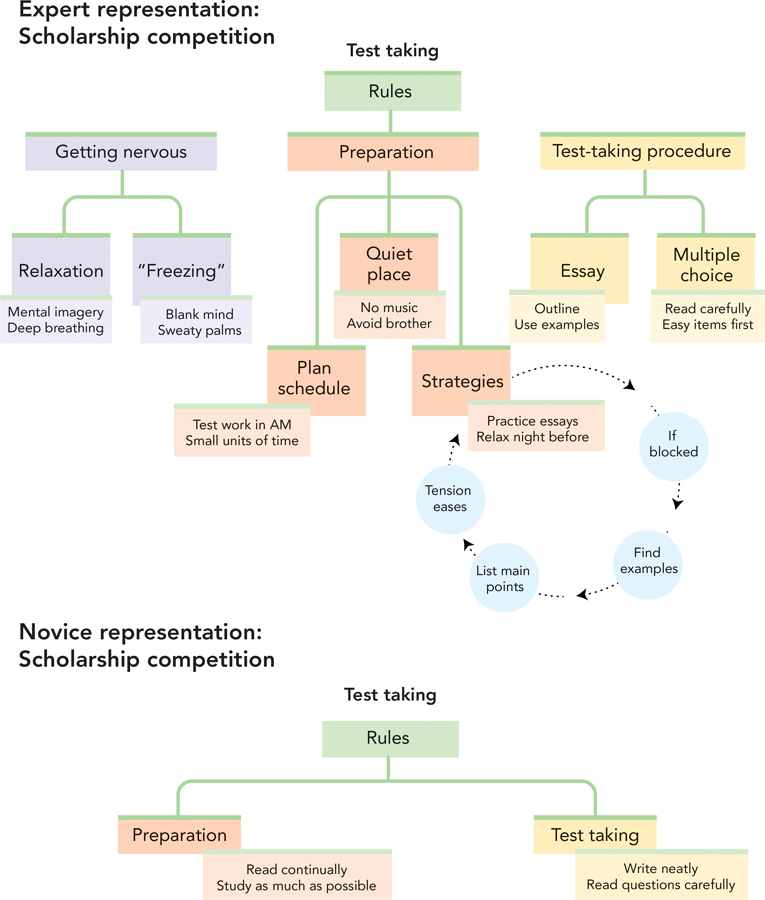

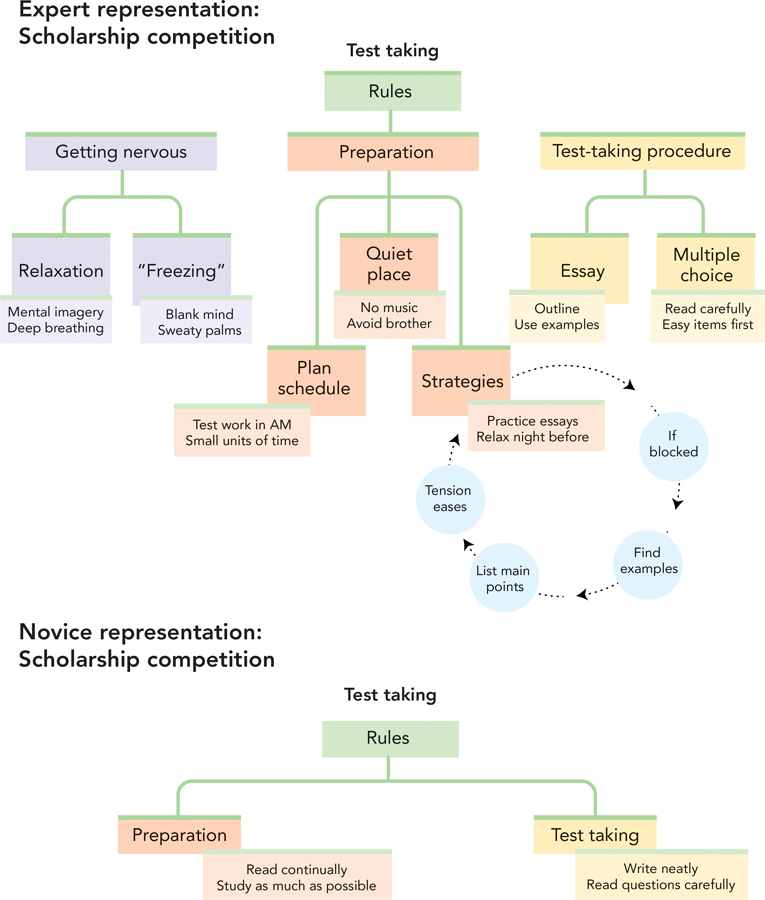

Differences in personality style, then, can reflect differences in skills. Some people develop a relatively high degree of social skill and knowledge about themselves. These personality “experts” are said to have a high level of social intelligence (Cantor & Kihlstrom, 1987). Their knowledge is a valuable personal resource; it helps them adapt to unexpected challenges in situations they encounter (Figure 13.9).

figure 13.9 Social intelligence The diagrams represent the knowledge possessed by two hypothetical people who differ in social intelligence (Cantor & Kihlstrom, 1987). The person whose knowledge is diagrammed on top is socially intelligent when it comes to exam preparation; this individual possesses a rich collection of knowledge about how to prepare for a test and cope with stress. The less socially intelligent person, depicted on the bottom, has a much more limited set of knowledge and strategies. In social-cognitive theory, such differences in knowledge and skills are seen as a key source of individual differences in personality.

AFFECTIVE SYSTEMS. People think, but they don’t only think. People experience moods that linger from hour to hour and day to day, and emotions that can flare up and dissipate in minutes. A comprehensive theory of personality must address this “feeling” side of personality.

Social-cognitive theory does this by proposing that thinking or cognitive systems of personality interact with affective systems. The word “affect” refers to “feeling states,” such as moods and emotions. Affective systems are psychological systems that generate moods and emotional states.

Social-cognitive theory suggests that cognition (thinking) and affect (feeling) are closely interrelated (Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999). Our thoughts influence our feelings, and our feelings, in turn, influence our thoughts. For example, perfectionistic standards for performance (a cognition) often cause people to become depressed (a prolonged negative mood). Perfectionistic people are more likely to develop depression than others (Enns, Cox, & Clara, 2002).

Conversely, negative moods cause people to become perfectionistic. People who temporarily suffer from a negative mood are more likely to develop self-critical, perfectionistic standards for evaluating their own behavior (Cervone et al., 1994).

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question

23

Match the personality structure on the left with the quote that exemplifies it on the right.

Question

24

3ljfuf4csq4KLWNVHP8sUKmhQWRb8bfQ22I8D1ayOEoPtWsaUz77b5SHKGdIExIEUqE0tX6Pzo8d9Fq4AoA8yG5aZF5I3tYqqsuUinqh8BQhBkbAe2qTqAHnY25u7c+bPAQkVNfRPMZQ59JZ

Answers will vary. If you feel highly capable of performing a challenging task, you might feel less anxious. Likewise, anxiety may influence your estimate of how capable you are to perform a task.

Process: Acquiring Skills and Self-Regulating Behavior

Preview Questions

Question

According to research by Bandura and others, through what process do individuals acquire skills?

According to research by Bandura and others, through what process do individuals acquire skills?

According to research by Mischel and colleagues, through what strategies can individuals control their emotions and impulses?

According to research by Mischel and colleagues, through what strategies can individuals control their emotions and impulses?

Beliefs, skills, and affective systems are stable personality structures; they comprise the structural aspects of social-cognitive theory. The theory addresses the process side of personality—changes in experience and behavior—by analyzing two topics: learning and self-regulation.

LEARNING. Where do people get their social skills? How did you first learn effective ways of participating in conversations, resolving conflicts with others, or making a good impression on people?

Social-cognitive theorists propose that the major way people learn life skills is through modeling. Modeling is the acquisition of skills by observing others who display those skills. If you learn to cook by watching a chef on TV, or learn to study more effectively by observing the study habits of academically successful friends, or learn to smoke by observing smokers light up (the behaviors learned can be both positive and negative), you are learning through modeling. People have the mental ability to remember others’ behavior and to use this memory to guide their own actions in the future (Bandura, 1986). (Modeling is also called “observational learning” because a person can learn new information and skills by observing others.)

Other people’s behavior thus serves as a kind of “instruction manual for life.” Instead of just guessing how we should act, we can observe others and learn from them. When learning the culture of the workplace at a new job, you don’t try out random styles of behavior—say, a formal suit one day, jeans and sandals the next—and learn only by trial and error. You observe the other employees and model their behavior.

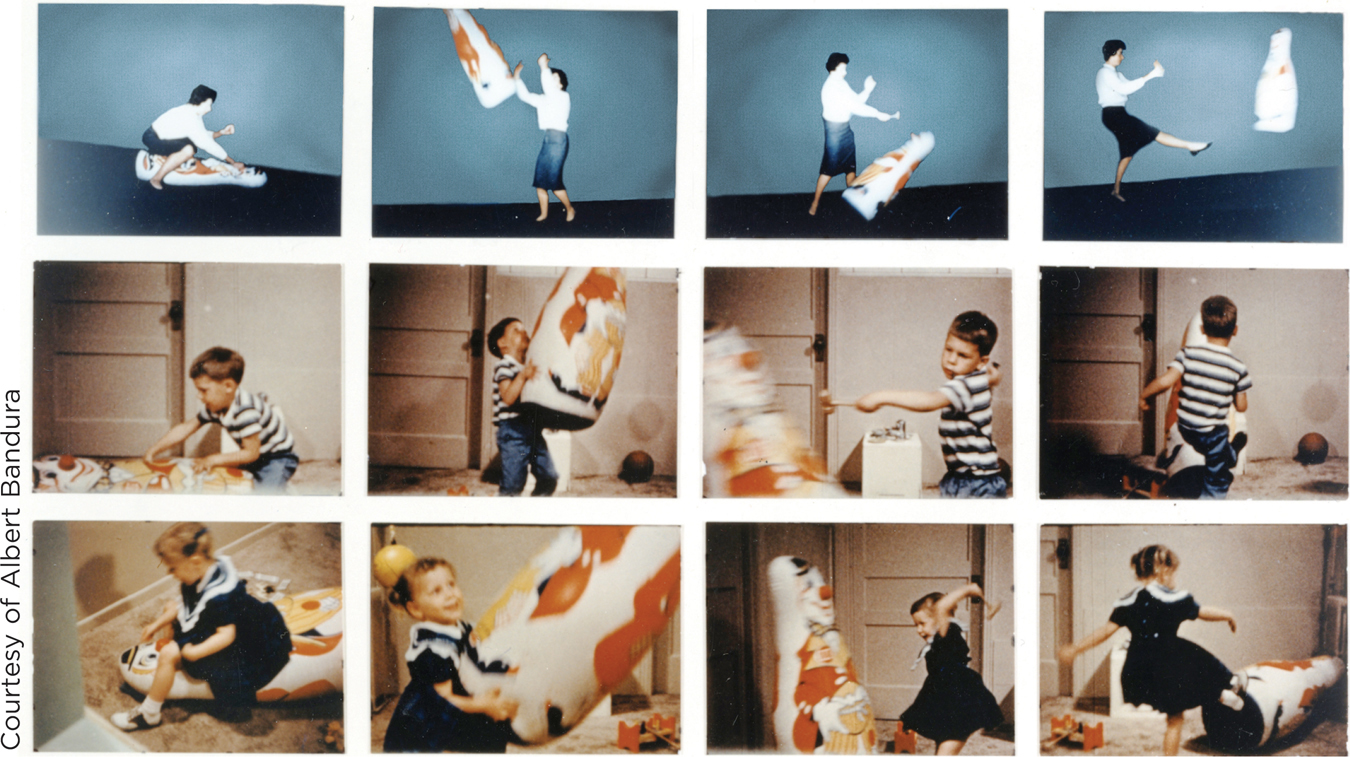

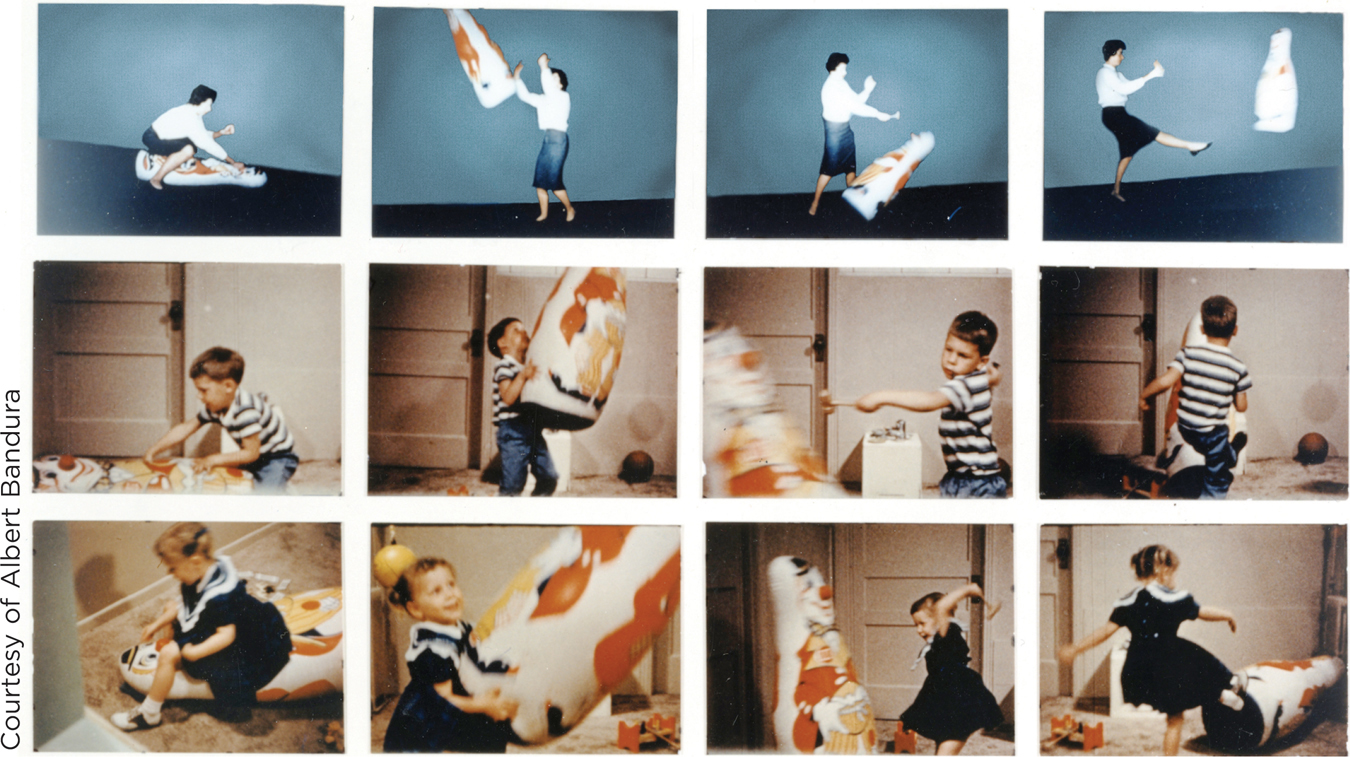

A classic study by Bandura and colleagues shows that even brief exposure to a model can powerfully influence people’s behavior (Bandura, Ross, & Ross, 1961; also see Chapter 7). Preschool children viewed a short film showing an adult punching and kicking an inflated clown doll, or Bobo doll. A second group of children, who constituted a control group, did not see the film. Later, children from both groups were sent one at a time into a playroom that contained a variety of toys, including a Bobo doll. Experimenters observed the children through a one-way mirror and recorded any acts of aggression toward the Bobo doll. As Bandura predicted, children who had seen the film behaved much more aggressively toward the Bobo doll than those who had not. They punched, kicked, and pummeled the Bobo doll with a hammer—just as they had seen in the film. They even devised novel acts of aggression toward the doll that went beyond what they had seen the model do.

As Bandura explained, this result contradicted the predictions of psychoanalytic theory. Psychoanalysis, as you learned, claims that aggressive energy is stored in the id. Viewing the film should have released some of this energy and reduced children’s later aggression. But just the opposite happened. As social-cognitive theory predicted, children became more aggressive; they acted like the model.

Subsequent research reveals that watching large amounts of violent television can have long-term effects. Children who watch large amounts of TV violence in childhood are more likely than others to develop into adults who behave aggressively (Huesmann et al., 2003). Violent video games similarly can increase aggressiveness (Bushman & Anderson, 2002). Although media violence, of course, is not the only factor that contributes to aggression in society, research shows that it does have a significant effect (Kirsh, 2012).

You can learn a lot from TV In Bandura’s research on modeling, children quickly learned acts of aggression they observed on TV. The televised model of aggression is shown in the first row of pictures. The behavior of two children, after seeing the model, is shown in the second and third rows.

THINK ABOUT IT

After they saw an adult hit a Bobo doll, children hit the doll, too. But Bobo dolls are made to be hit; given their design (bouncing right back up after being knocked down), hitting them is natural. Do you think that, as social-cognitive theory seems to suggest, the children would have modeled the adult’s behavior no matter what she had hit (e.g., a potted plant; a piece of candy)? Are some behaviors more readily modeled than others?

Modeling influences also can be positive. People who model socially valuable behaviors can have beneficial effects. Sometimes these effects are widespread. Consider a project in the East African nation of Tanzania, which suffers from high rates of HIV/AIDS infections (Mohammed, 2001; Vaughn et al., 2000). Social scientists working in collaboration with government officials designed a radio soap opera that educated listeners about HIV/AIDS. Some of the show’s characters provided information about the causes of the disease. Other characters initially did not engage in safe-sex practices but, thanks to the positive influence of others, gradually adopted them. The show thus provided models of behaviors that promote health.

CONNECTING TO LEARNING AND THE BRAIN

The government evaluated the program through an experiment of incredible scope. For two years, the show was broadcast in some regions of Tanzania but not others. Researchers conducted surveys to gauge its effects and found that the radio broadcast significantly improved the health behaviors of the nation’s citizens. In areas where the show was broadcast, Tanzanian citizens reported more awareness of the risks of the disease and fewer HIV/AIDS risk factors (such as unprotected sex; Mohammed, 2001; Vaughn et al., 2000).

SELF-REGULATION. The second personality process of interest to social-cognitive theorists is self-regulation. Self-regulation refers to people’s efforts to control their own behavior and emotions.

Sometimes people “give in to” impulses and emotions. You don’t feel like doing your assigned reading, so you surf the Web instead. The triple-brownie delight looks good, so you order two. These are not cases of self-regulation. People self-regulate when they overcome impulses and emotions through their powers of thinking.

A major advance in scientific understanding of self-regulation was made by Walter Mischel, who studied a self-regulatory challenge known as delay of gratification. In delay of gratification, a person tries to put off (i.e., delay) an impulsive desire. For example, putting off a late-afternoon desire for a burger and waiting until dinner time to eat would be a case of delaying gratification. In Mischel’s research, children in a nursery school were told that an adult who had been taking care of them had to leave for a while, but would come back. Before leaving, the adult left several marshmallows on the table in front of the children. If the children waited until the adult’s return, they would get a reward: some marshmallows to eat. If they couldn’t wait, they could ring a bell, and the adult would return—but the child would get only a small reward: one little marshmallow. Because children had an impulsive desire to eat the marshmallows, the length of time they waited was a measure of their ability to delay gratification.

The nonprofit organization PCI Media Impact (formerly named Population Communications International) has put principles of social-cognitive theory into practice. They produce media broadcasts in which characters model beneficial behaviors, such as safe-sex practices. Here, broadcasters in Mexico work on the TV drama program Mucho Corazon (Much Heart), whose characters confront and cope with issues involving gender-based violence, financial literacy, and sustainable development. PCI Media Impact has produced approximately 100 TV and radio serial dramas that have reached over 1 billion people in 50 countries.

The scientific question Mischel asked is: What can people do to delay gratification? In other words, what psychological processes enable people to control their behavior? He found that a major psychological process involves attention. What children pay attention to, while waiting, strongly affects their success at self-regulation. In a key study (Mischel & Baker, 1975), attention was manipulated experimentally:

In one experimental condition, children were instructed to pay attention to how tasty marshmallows are: “When you look at marshmallows, think about how sweet they are when you eat them … how soft and sticky they are in your mouth” (Mischel & Baker, 1975, p. 257).

In a second condition, children were distracted from the taste of the marshmallows; their attention was drawn to qualities other than taste: “When you look at marshmallows, think about how white and puffy they are. Clouds are white and puffy too—when you look at the marshmallows, think about clouds” (Mischel & Baker, 1975, p. 257).

Children whose attention was directed to qualities other than taste were much better at delaying gratification; they were able to wait 3 times longer than children who thought about how tasty marshmallows are. The findings show that the human ability to control thinking—to exert “executive control” over the flow of one’s thoughts (Chapter 6)—enables people to control their impulsive desires.

Children differ in self-control abilities; some are better able to control their impulses than others. These differences predict outcomes later in life. Children with higher self-control skills tend, in adulthood, to experience better physical health and lower rates of substance abuse and are less likely to commit criminal offenses (Moffit et al., 2011; see Chapter 14).

Want to avoid ordering a lot of fast food? If so, don’t look at the picture or think about how good it would taste. Mischel’s research on delay of gratification shows that forming mental images of things you want to avoid makes it harder to avoid them.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question

25

- RAP8i+zEhc0JILicLINwHi/zl2eie+k0mkJJBXP+Yj90l2osSanXseT2pknWQS8oc9bQjvFQ8mWvLOoZlf5QEtrxbkNdQJq3AOvu0IJE20TeYie8z201sjBdZOpgCkyxOsO2A/IKlyLFzzhGy/7kLnI8tL3Kll+L8z8b2C95uDpNvfkpE5bsv+s/BAwAoqD1sQXKy7U7oFISHsGUzbp7Awa7LjtWX1s/Wibw4xscqc3a4LHOWPR/VSN2jVAfhnLa

- Ri3g1x2If06hYUqXQOWsBEhZGNIhNoRsohdDwKx30abNuelT9e4tsro74IIZR/Up+bn02S3p4/RRZ0uUTAyGUOU/FU6UrPytPN+yQMrU7FHBhJVVocUMb604p4Db7Pd4fxXy0rW88kdxRxczcFIx4FfElbMgQnTRhpshjC7fwv7FBKNLLuwF/vNlO04=

- MowixIC7/UjnOosu3g/ONnxlxL6VMGvcbadVS67NiTs7FmoDRiumlIFZVYYHu70Ug1DhyqeMwB7Uf8Xetc0D8c+9GcyPBElOcT6RiKHq07tgSYf5cSacggDDTr9iHbchbIPvMpYIy/lNbI+kFS9VVLmAmJ2qf2JS9pYzvgobIqEcaTUbVxAzJoC2vyyygHChA+rWSipc8rOAQdq5wAmZ/H9eszMUDrDaBKMyJzuiJ6uR+goDU/V6mDrzVJi7XtI8SDqF3vNn2i4iklgd

- LTm0GEcovGUSUpKlYDmZ5s2fpy+Otmo7/qr5P0czs5Z9TvgI+xt41YeIt57VN+rjzlWQ3UcFbEhBwfy0uHlcP6ALH1ZW2PgvEhmf1HfmdPhtEevFDF+MjWfVEGdiYVVCFEwowiIxU0uPYFCNExoL55JHK+wYWyAq8IT6MWbRhzcGwM1E

- iGyRwdQipPx1rxP+ll+XSdxHTGgSm/VoWnd648thnkGOR4lH37NSSHjyPEdbaLdFwF1MDdkJkBNchDBhVLCDG3R3qAw8BArPJhy/SoppB6FZ1+0FsTj4SM6vEvkIZNO12+EJYoPovC86svKcyViAUdA70B00cKDDt7wHh0t2RPWrNUyiIrbbGqbQMmVyEFocyMT9r0Ei/hWrF5naAiwtX3O2CdUMkg4eqpZz7aPLjIgkeH8KRt8DdF+0ON4=

- 42MvaDds+e5ySKahGyUlnJChum8ahC5YiB1BXyBWurb70WRxyOAzTfmlfIqcEGHFG4MOdhTj0hqWt7BwGR8jsmQUU5+0rHv84jNh7YYW3HgFvrdmPSQGX2yXGKUSvmy6CpshHkO1Owp2QrqFLT4n6Ttt6YaLpZg8wwX9tERCz6HTL1q+qdElmIJ4Deh8wyHP8+As8OpqP1LLnYwZiyEg1tYY2BOGN8CC

- oNQC7/Ny4ktd0qbqo5IsjXBWkxUbNCv7tQlN3t+MJ9SZ9GiwPQTHik7WZXEZoYiZxp4m4T7qO7iKiysUWWyTdMPNxP2jkUeIqf1PAiz1aOe9M9gsMHZkU/HCxiLw8W2vP8aJLXHaD4PYXg+jzgmVcNyuSXIGUQjp/e/2F4mk8nQm7StkfWo6fltxTOHpEKO1ynEoJpRYApRfEx4mke/euXVxehoDDiIk

Assessment: Evaluating Persons in Context

Preview Question

Question

What does it mean to assess cognition and behavior “in context”?

What does it mean to assess cognition and behavior “in context”?

Social-cognitive theory, as you have seen, highlights (1) thinking processes and (2) the impact of thinking on behavior. When social-cognitive theorists assess personality, they have these same two targets in mind; they try to assess both thoughts and behavior. Before reading about how they do it, ask yourself this question: What are your thoughts and behaviors like? If you think about it, you will realize that the best answer to that question is, “It depends.” You think about different things in different situations (at school, at work, with friends). Your behavior varies across varying social circumstances (with family, with one close friend, with a group of people you don’t know well). Social contexts—the situations of your life—matter greatly.

Social-cognitive personality theorists recognize this. When assessing personality, they measure people’s thoughts and actions as they occur within specific social contexts that are significant to people’s lives (Cervone, Shadel, & Jencius, 2001; Shoda, Cervone, & Downey, 2007). (Note how this contrasts with trait theory, which assessed typical, average personality tendencies and thus paid much less attention to social context.) Let’s look at some methods used to do this.

Perceived self-efficacy in the context of school Research on social-cognitive personality variables and school success shows that one determinant of success is perceived self-efficacy. Adolescents who are more confident in their abilities develop into more outgoing and assertive students.

ASSESSING COGNITION IN CONTEXT. One method for assessing personality and thinking processes is self-report: asking people to report their beliefs about themselves and their actions. People usually give a lot of thought to themselves, their goals, and the personal standards they try to live up to. As a result they are, in some ways, “experts” about their own personality (Cantor & Kihlstrom, 1987). Social-cognitive theorists often draw on this expertise by asking people to report information about themselves.

Assessments of self-efficacy illustrate the strategy. Researchers ask people to report their confidence in performing specific types of behavior in specific settings (Bandura, 1997). For example, in a study of adolescents in school (Caprara et al., 2003), students were asked to report how confident they were in performing actions in specific contexts, such as “express[ing] your own opinions when other classmates disagree with you.” These self-efficacy measures predicted behavior over a long period of time. Children who initially had higher self-efficacy beliefs regarding behavior at school were less shy at school two years later. Self-efficacy beliefs predicted behavior even after accounting for children’s behavioral style at the start of the study (Caprara et al., 2003).

A second assessment strategy is implicit measures of personality, that is, measures that do not rely on people’s explicit reports about themselves (see Research Toolkit). In social-cognitive psychology, the speed with which people respond to test questions is a commonly used implicit measure. People who, in their everyday lives, tend to dwell on a particular feature of their personality tend to respond more quickly when asked questions about that personality feature (Cervone et al., 2007; Markus, 1977).

THINK ABOUT IT

In their assessments of self-efficacy, social-cognitive researchers presume that people who (1) say they are confident in their abilities (2) actually have higher confidence, that is, higher self-efficacy beliefs. Is this always true? Maybe some people have doubts, but say they are confident in order to hide their doubts from others—and maybe even from themselves.

Implicit Measures of Personality

“Tell me about your personality.”

This might seem easy. Everybody can tell you something about their personality. But is what they tell you accurate?

Two factors can create inaccuracy. People might not have an accurate conception of their personality. Alternatively, they might be motivated to create a good impression and thus describe their personality in a false manner. For example, people applying for a job that requires employees to act in an extraverted manner (e.g., sales or marketing) may describe themselves as extraverted—even if they’re really not (Krahé, Becker, Zöllter, 2008).

To measure personality accurately, then, researchers need tools in addition to self-reports. One such tool is implicit measures of personality (Gawronski, LeBel, & Peters, 2007; also see Chapter 12 for a discussion of implicit measures).

The term “implicit measure” is most easily defined by first considering its opposite: explicit measure. An explicit measure of personality is one in which people directly state answers to questions, and the substance of their answers is interpreted as an index of their personality qualities. Interviews in which people discuss their personality, or questionnaires in which they describe themselves on rating scales, are explicit measures. An implicit measure of personality is one in which responses other than explicit self-reports provide information about personal qualities. For example, the length of time taken to answer a question may be revealing; people who take longer to answer a question may be hiding some aspect of their true self (Weinberger, Schwartz, & Davidson, 1979).

Let’s see how implicit measures work in a specific case: measuring self-esteem, people’s overall sense of self-worth.

In an explicit measure of self-esteem, participants simply make statements about themselves. Researchers might, for example, ask them to indicate whether “I have high self-esteem” (Robins, Hendin, & Trzesniewski, 2001, p. 153).

One popular implicit measure of self-esteem is the implicit association test (IAT, Greenwald & Farnham, 2000). In an IAT measure of self-esteem, people perform tasks that involve positive and negative ideas about the self. Their relative speed in making positive and negative responses on these tasks indicates their self-esteem level. In one task, people decide whether words fit the following rule: The word “is pleasant or describes me.” In another, they decide whether each word “is unpleasant or describes me.” Greater speed on the former task (pleasant or me) than the latter indicates a higher level of self-esteem. The speed reveals stronger mental associations between the concepts of “pleasant” and “self.”

Intriguingly, implicit and explicit measures of self-esteem are not strongly related (Hofmann et al., 2005). Some people with low implicit self-esteem have high explicit self-esteem (and vice versa); they seem to doubt themselves, but don’t express these doubts publicly. The implicit measure, then, provides unique information. It may reveal, for instance, that someone who speaks highly of herself publicly also has—at a hidden, implicit level—substantial self-doubts.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question

26

Researchers concerned about the accuracy of NbGWhlJsxcue1a1X3lqPxQ== measures may wish to instead rely on implicit measures of personality. On the IAT measure of self-esteem, high implicit self-esteem would be indicated if someone was faster to associate “describes me” with UZZczAxcUvduRZWoBBCayg== words. Implicit and explicit measures are not strongly eZ5S66kdZtS/jpiv, indicating that the implicit measures do indeed provide unique information.

ASSESSING BEHAVIOR IN CONTEXT. The second target of assessment for social-cognitive theory, after thinking processes, is people’s behavior. A particularly valuable method for assessing behavior was developed by Walter Mischel and colleagues. In the if … then … profile method, researchers chart variations in behavior that occur when people encounter different situations (Mischel & Shoda, 1995). The technique rests on the following idea. If you look at people’s behavior, it varies. For example, you might be extraverted with close friends and introverted around strangers. Why average together these different behaviors in different situations (as is done in the trait approach)? Instead, assess the variability: “If you are with close friends, then you are extraverted,” but “If you are with strangers, then you are introverted.”

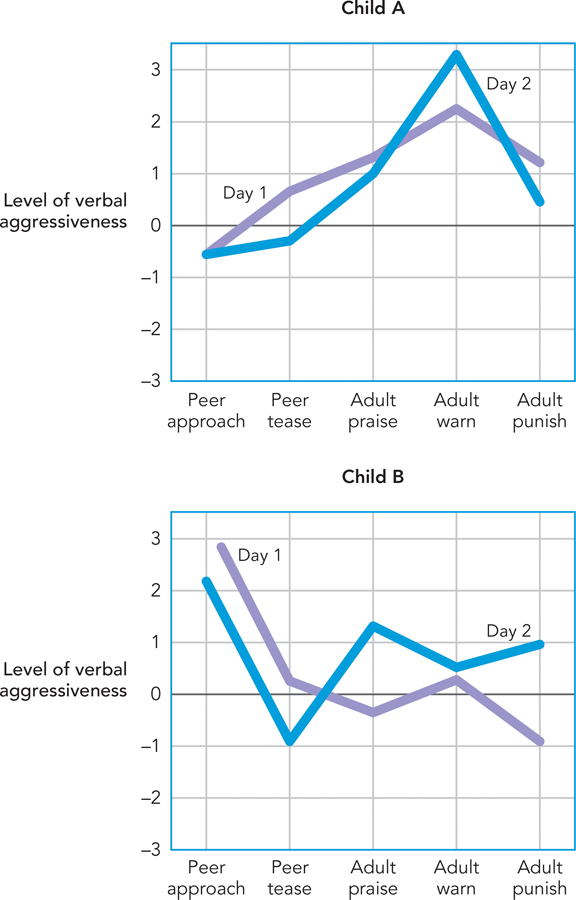

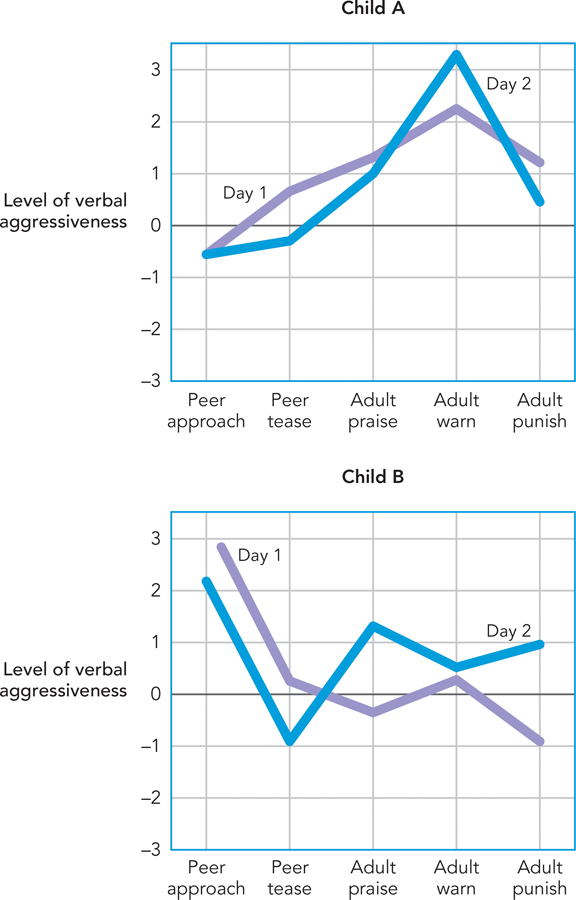

The if … then … profile method has been used to study children’s aggressive behavior (Shoda, Mischel, & Wright, 1994). Psychologists recorded not only acts of aggression but also the particular situation a child was in when acting aggressively. They then plotted if … then … graphs showing how each person acted in different situations (Figure 13.10). Children who, on average, displayed similar levels of aggression differed from one another in the situations (the “ifs”) that triggered their aggressiveness. For instance, some picked fights with other children but were not aggressive toward adults, whereas others were aggressive toward adults who reprimanded them but did not pick fights with other children. The profile method, then, reveals personality characteristics that would be missed if one only studied average levels of behavior.

figure 13.10 Personality in context Social-cognitive theorists explain that, to learn about personality, you should study people across a variety of social contexts. If … then … profile graphs show how personality reveals itself in the way that people’s behavior varies from one context to another. The two graphs represent two children’s levels of verbal aggression in each of five different social contexts involving interactions with peers and adults. The two lines in each graph represent the child’s behavior as measured on two different days. On average—that is, if you averaged across the five contexts—the children score about the same. However, their reactions to specific social contexts are entirely different (Mischel & Shoda, 1995).

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question

27

Social-cognitive assessments are designed to find out what people are like in 6ZDQbE3oF+f0JRu990WiXfWE7rjASe6b versus what they are like on average. Research using the if … then … profile method revealed that children differed in the 2l38+T2XjjFPLgxBhaRW3A== that provoked aggression.

Evaluation

Preview Question

Question

What are the strengths and limitations of social-cognitive theory?

What are the strengths and limitations of social-cognitive theory?

Social-cognitive theory has many strengths. It is supported by a firm base of research. That research base is diverse; it includes research conducted in the laboratory and in the real world, with adults and with children. By attending to social situations, social-cognitive theory helps to show how personality develops in interaction with the settings in which people live.

Like other theories, however, social-cognitive theory also has its limitations. It does not directly address some important phenomena. The theory says little about how unconscious motives, particularly those involving sex and aggression, can express themselves in people’s actions (a main concern of psychodynamic theory). It does not explicitly explain how the quality of interpersonal relationships can enhance personal growth (a main topic in humanistic theory). In addition, its assessment methods are valuable yet complex; they do not yield simple, quick assessment measures (of the sort provided by trait theory). But social-cognitive theory is still evolving. Expanding its scope is a challenge for its future.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question

28

Which of the following statements about the strengths and weaknesses of social-cognitive theory are true?

- hsQbVKF/z616ugOTSMv7JJES5Kg+rl4DmavClSP3wAhbtxlyniGfbb/Ezs9HJvRgXd8WCiBodsUMmM3e3rgvZVe5oY/YIxp20rncpcXB+kIisLFu69Ou5UQxYndEXdeWQJM2LT5d5a81kJ2J8e5f47ZChIIPtL2FT4sWOWcPJkK9XqE13RwXsja5WsDZJ7+PolsK9LVbcauC+mE8LLDoIfRSOHAXYV5g98IG23lU8fE=

- 5OqEwniHynSJvulUiYDWJffR7uXvJP9Uu+z/rT/8/FKL6UOy8S0NNiUE2SnKBTd041yggNY9wzNuUimYrLKGCnZq1n9xovyJJLEL88eucI9Ui8TWa/e/sqfkEfCmF0Ws+MtfGOTTwWJBa6YgIjGCw1Oyod/mq0GW

- tylhMPg4KS+57TzaLJX6BSvY6d0ZAZ3xWFHSrYKyhDX5JBd+llwBhALYYrO3gb/+g1tohWJiOxGi9N9yLq3jf82J2Ydlp2jcyuuaCsRxHo0Bp4U1KkDCrdamvMjHXvKwVe4KsypCG0+bitCXpPwBfRpN1tuZ+kXt

- DwqIcSiwpkyK5fifwrJzrfGf0VUEBVS8e5AEk2Rg310pXJ/h7HtFWN0EB4REOqaEWbGa4BQNiMn4HQLpoHD04XDWBn4wAV2AwlrLubW9mp+hh5eirj8isZnR+0h4SoSf1uzlGWZnq6TD2hCWg+LR+ewr9lPg36Ci/4Lcag==

- p/dzVeVRMQDaMEKp4ILMIotwk7UrUzErKu2AQ7DTslPXF/hC2Im84JLWHepmR6quX3zaz8OecS+/jllvkRMoPCqYG5nzzthTU45HAk5NrYCwGqZMLX/98YuzTorAByhKKwlTtQw57Rnz6Adn9l5gkti+TH4UCJrduVqhvqVhVB7qebhP7ZeAvg==

We’ve reached the end of our survey of personality theories. Table 13.6 summarizes their structures, processes, and assessment strategies. With this information now in place, let’s turn to the topic of personality dynamics and the brain.

| Personality Theory Structures, Processes, and Assessment Strategies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conscious and unconscious mental systems: id, ego, and superego |

Anxiety and defense mechanisms |

Free association and projective tests (e.g., Rorschach test) |

|

|

Self-concept: the actual and ideal self |

Self-actualization, conditions of worth |

Measures of self-concept (e.g., Q-sort technique) |

|

|

Stable individual differences in average behavioral tendencies |

Trait-based individual differences in reactions to stimuli |

Comprehensive self-report questionnaires (e.g., NEO-PI-R) |

|

|

Socially acquired cognition (self-referent cognition, skills) and affective systems |

Acquiring skills, regulating emotion and behavior |

Contextualized measures of cognition and behavior (e.g., self-efficacy measures, if … then … profiles) |

What did social-

What did social-

What defines each of the three different types of personality structures within social-

What defines each of the three different types of personality structures within social-

According to research by Bandura and others, through what process do individuals acquire skills?

According to research by Bandura and others, through what process do individuals acquire skills? According to research by Mischel and colleagues, through what strategies can individuals control their emotions and impulses?

According to research by Mischel and colleagues, through what strategies can individuals control their emotions and impulses?

What does it mean to assess cognition and behavior “in context”?

What does it mean to assess cognition and behavior “in context”?

What are the strengths and limitations of social-

What are the strengths and limitations of social-