14.2 Social Development: Biological and Social Foundations

The next time you have a chance, pay attention to some infants. You’ll notice they differ. Some are active and energetic. Others frequently nap. Some are happy and easygoing. Others are cranky.

The differences are partly based in inherited biology. Genetic differences (also see Chapter 4) produce varying temperament.

Biological Foundations: Temperament

Preview Questions

Question

What is temperament, and why do psychologists study it?

What is temperament, and why do psychologists study it?

Is temperament the same in all contexts?

Is temperament the same in all contexts?

Temperament refers to variations in emotional and behavioral tendencies that are evident very early in life and are based, at least in part, in inherited biology (Zentner & Bates, 2008). Differences in emotional reactions—

Temperament has intrigued scholars for ages (Strelau, 1998). In ancient Greece, the physician Hippocrates said that people possess four temperament styles, based on excesses of certain bodily fluids in an individual’s system. Excess black bile, for example, was said to produce a sad, moody temperament; excess phlegm, he thought, created a calm, peaceful, phlegmatic style.

Although it was popular for more than 2000 years, Hippocrates’s theory is wrong; the bodily fluids he proposed are not the source of temperament. Yet his work resembles contemporary ideas in a number of ways. Like Hippocrates, many scientists today search for a small number of temperament styles with biological origins.

Two pioneers in this search were Alexander Thomas and Stella Chess (1977). To study temperament, they interviewed parents. Parents reported their children’s behavioral characteristics (e.g., “How much does your baby move around?”), regularity of daily experiences (“Could you tell … when during the day [your child] would be hungry, asleep, or awake?”), and adaptability (“How would you describe the way your child responded to changed circumstances?”) (from Thomas & Chess, 1996). By analyzing these reports, Thomas and Chess identified three types of temperament, that is, three temperament categories into which individual children could be classified:

619

Easy temperament: Calm, cheerful adaption to new situations

Difficult temperament: Intense negative reactions to unexpected events and slow to adjust to changes in routine

Slow-

to- warm- up temperament: Mild negative reactions to new events, but positive reactions develop if a situation is experienced repeatedly

Later psychologists followed Thomas and Chess’s lead, but with a change in emphasis. Rather than focusing on temperament types, they searched for temperament dimensions. A temperament dimension is a biologically based psychological quality that all children possess to a greater or lesser degree.

Three important temperament dimensions are emotionality, activity, and sociability (Buss & Plomin, 1984; Table 14.2). Some children are more easily upset than others (emotionality), some are more energetic (activity), and some show a greater preference to spend time with other people (sociability). Many personality psychologists view these temperament dimensions as early-

What were your levels on each of these three temperament dimensions?

One way to measure temperament is to ask parents to report on the qualities of their children. Three main dimensions of temperament identified with this measurement strategy are emotionality, activity, and sociability; the test items shown are designed to measure the dimensions. Note that the item marked with an asterisk is “reverse-

| Measuring Temperament Dimensions | |

|---|---|

|

Emotionality |

|

|

Activity |

|

|

Sociability |

|

14.2

Research from Buss & Plomin (1984); Spinath & Angleitner (1998)

620

THINK ABOUT IT

Temperament is biologically based. The biology of the brain consists of large numbers of neural systems and large numbers of neurotransmitters through which brain cells communicate. The biology of inheritance consists of thousands of genes. Does it seem right that the number of temperament dimensions is only three?

THE LONG-

Researchers in Norway observed children at ages 18 months, 30 months, and 4 to 5 years (Janson & Mathiesen, 2008). At each age, they classified children into the Thomas and Chess temperament categories. Many children displayed consistent temperament across time. Almost half the children had the same temperament at 30 months as at 18 months, and almost half had the same temperament at 4 to 5 years of age as at 30 months.

Researchers in Finland measured temperament in a large group of teenagers (Hintsanen et al., 2009). Nine years later, they determined the employment status of these same individuals. Teenage temperament predicted adult employment. Teens whose temperament featured high levels of activity and low levels of negative emotion were more likely to be employed.

These are but two of many examples in which early-

SHYNESS. Many people say they are shy. In one survey, 40 percent said so when describing their present self, and 80 percent said they were shy at some point in their life (Zimbardo, 1977). High rates of shyness may be found in all cultures (Saunders & Chester, 2008).

In what situations do you feel shy?

Do you think that all people who claim they are shy are psychologically the same? Harvard University psychologist Jerome Kagan does not think so. His research findings suggest that a subgroup of people is distinctive; they inherit inhibited temperament, which is a tendency to experience high levels of distress and fear, especially in unfamiliar situations (the fearful reactions trigger shy, inhibited behavior) or in the presence of unfamiliar people. Furthermore, a second distinct subgroup inherits uninhibited temperament, a tendency to experience little fear and to act in a spontaneous and sociable manner. Before detailing his findings, let’s examine his research methods. Kagan was wary of relying on parents’ reports because parents’ views of their own children could be inaccurate. They might, for example, see their child’s behavior as wonderfully unique when it actually is commonplace (see Saudino, 1997; Spinath & Angleitner, 1998). Kagan thus brought children to his lab, where they could be directly observed by researchers.

621

Children first visited his lab at 4 months of age (Kagan & Snidman, 1991). Kagan videotaped them while they were exposed to novel events, such as a popping balloon. They returned at 9 and 14 months of age, when they again were exposed to novel stimuli (e.g., flashing lights, an unfamiliar loud toy, an unfamiliar adult). At age 7, they returned again and were observed while interacting with peers. Kagan hypothesized that two subgroups of children—

CONNECTING TO EMOTIONS AND BRAIN STRUCTURES

Findings strongly supported his hypothesis. Children who had reacted fearfully at 4 months of age reacted fearfully again at 9 and 14 months. Most who were uninhibited at the earliest time periods remained uninhibited later. At age 7, the children who had been inhibited infants were shy when interacting with peers (Kagan, 1997).

These results show that temperament is often stable across long time periods. This, however, does not mean that temperament cannot change. Some experiences can alter temperament. One is childcare outside the home. Researchers compared inhibited children in either of two types of settings: (1) entirely in a home environment, or (2) multiple hours each week spent in childcare with teachers and other children. Childcare altered temperament. Socially inhibited children who spent 10 or more hours a week outside the home became less shy (Fox et al., 2001). Another factor is parenting. Mothers who avoid being overly protective of children tend to produce children who are better able, on their own, to develop strategies for dealing with fears and anxiety (Degnan et al., 2008).

Temperament is a biological foundation for social development. Another foundation is the family—

622

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 8

Which of the following are true of temperament?

- FfoJVLG5kkPr8m5LCRh0x8TagvG3cyc6xswIn/45WoqkfzgKLgOux5jMhKlWzHiY5HJJn/oUC2QRomqmjTIS5eNvgHx7jFGm0UFAaabNuuh0kq7GhPNmfKBcWQhxPK+QmReWAHQecLgUp2lpCfL0k3/ZHjKpnqBx3NR+wddLKCR8GKWC5upfa01c1wRLHkNihuaSag==

- 69qSZIK+Uou2+rUlQ5s84LdTWoFblLFPMOOstNZnNwu0EZLcyoPNMiq5llBcn359no3+yVrxNGsKglJc7IAPmU/NXZtOhxE0YBwvupPypx/oxorRasEh5Ga1yLFDXZ8DZhMRH60MBTDzHJrWfGLXZ6+Q4HgR94BFftGodfvJRKDzNc+HwAb7KRVXK9xAQc4L3CqjW3uulPK4UN0EGT1Z6tWf/QlbnEQUQBcYIue0zXg9ngKwoA6CfdKijPGpay5fgzoUS7BW/jo=

- QRVhV6/frDcgGw2cMb5rVDL6dN/odJQc2BFSE/zX8o1K63kOvx1uZ9hK6B3ZLYSRdwlLCwzfYOF3N2fPya4MUp/OKXNfEY1EwdjCGqEKzVYeclF1p3+SJ3D9XYUVz7ai5qClal5yhiDaJW3i7Svi9ds36GpkDTu4VPIGI5ia0gF6vaHZfLPsa62kyzo0d9dj7v8LzeG8y9g0cWU6U2RQXP6ico91iLw/B2EW+ZR05snykT31ybnw4rh7nUM=

- 8KZEMgz5syzi/VSi2LCJqkVA4T/00jfihQAllCFpu/2N/+Ba8Kynj0YC/GnUTNa6RMYWyROhoNJD1KYL5egaGXqHuEG60Bwp5GJCeKJsYaicLdJ4q1QXXjrKG8TW6hexcVzOVlR1OyqdSGk9zoN4Iy4RlqrEyBzb9REuMFAmrdmCn/Z00lBZbmx1+fqAX9UVs35rfrDBzBUFffVU

- xi43LBuC+2SNNwDbukXuvMWY+OQZMTZzZQCIbnXe297ApPaVvf0oQfU7vn2Zd3mn9kREYbJk/YHNMpv2aDV7ZUVsBH1CMhgwnUgFDqI3Op91+uLUZFuBXlexBP4boi5Sj6I3So0SkSrJWtfrR5QFqKtKI57u81EEGY08Mpkr0yda8jQ40D/WeagaL5sYP1CBBDUd+O37VDk=

Social Foundations: Bonding Between Parent and Child

Preview Questions

Question

Why do goslings follow Mother Goose?

Why do goslings follow Mother Goose?

Food or physical comfort: Why do babies bond with caregivers?

Food or physical comfort: Why do babies bond with caregivers?

According to attachment theory, how do early life experiences exert lifelong effects?

According to attachment theory, how do early life experiences exert lifelong effects?

How can putting children in a “strange situation” help us to understand attachment styles?

How can putting children in a “strange situation” help us to understand attachment styles?

Do negative childhood experiences scar us for life?

Do negative childhood experiences scar us for life?

Across animal species, the development of offspring depends on the support of parents. Let’s start our review of family foundations of development with a phenomenon that occurs in species other than ours: imprinting.

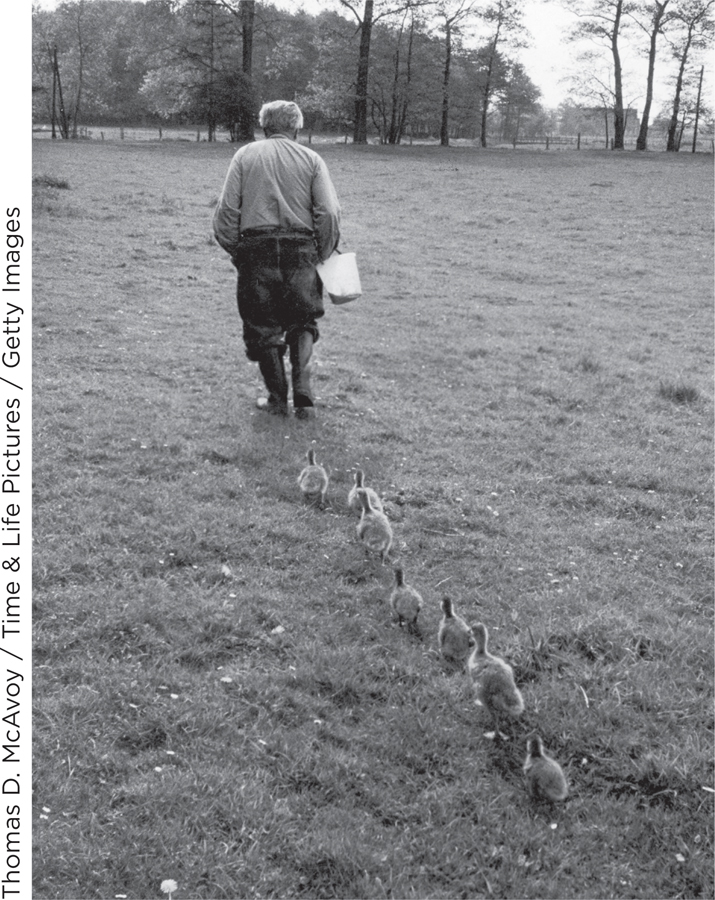

IMPRINTING. Look at the photo of baby geese. It shows them following … a man? Shouldn’t they be following Mother Goose?

The geese have imprinted on the man. In imprinting, newborns fix attention upon, and follow, the first moving object they encounter (Sluckin, 2007). That object is usually the mother; imprinting therefore bonds mother and offspring. However, newborns of some species will imprint on almost anything that moves. Imprinting occurs only in species whose young are able to move about soon after birth (Hess, 1958); thus, it does not occur in humans.

Lorenz (1952/1997) explained that imprinting occurs only during a critical period. A critical period for a given psychological process is a span of time, usually early in life, during which the psychological process must occur if it is ever to occur (Hensch, 2004). A gosling, for example, will imprint on a moving object only if the object is encountered in the first few hours after birth. Once imprinted, the bond is permanent.

CONTACT AND COMFORT. In species that do not imprint, children still bond with parents. What drives parent–

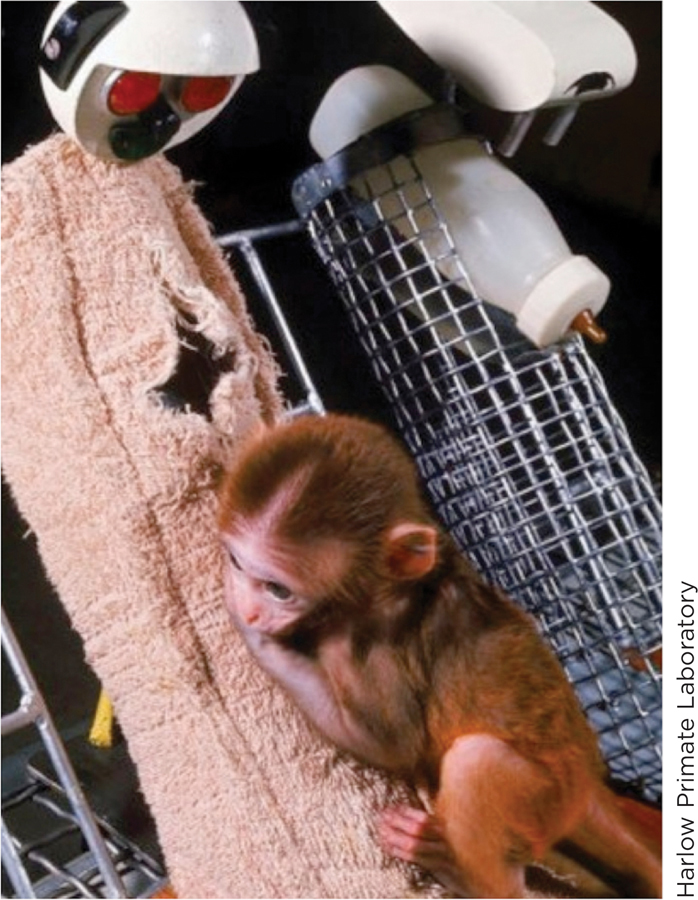

Harlow studied infant macaque monkeys, whose early-

623

Which “mom” did infant monkeys prefer? Warm and cuddly mom. Throughout the first month of life, they spent much more time with this artificial mother than with the wire food-

Contact with a comforting mother is not only preferred; it is necessary. Infants need this contact for normal development. Monkeys who lack it display abnormal behavior as adults. Consider the fate of female rhesus monkeys that had no contact with a comforting mother during infancy. When, in adulthood, they became mothers themselves, they behaved abnormally, neglecting their own offspring (Hensch, 2004).

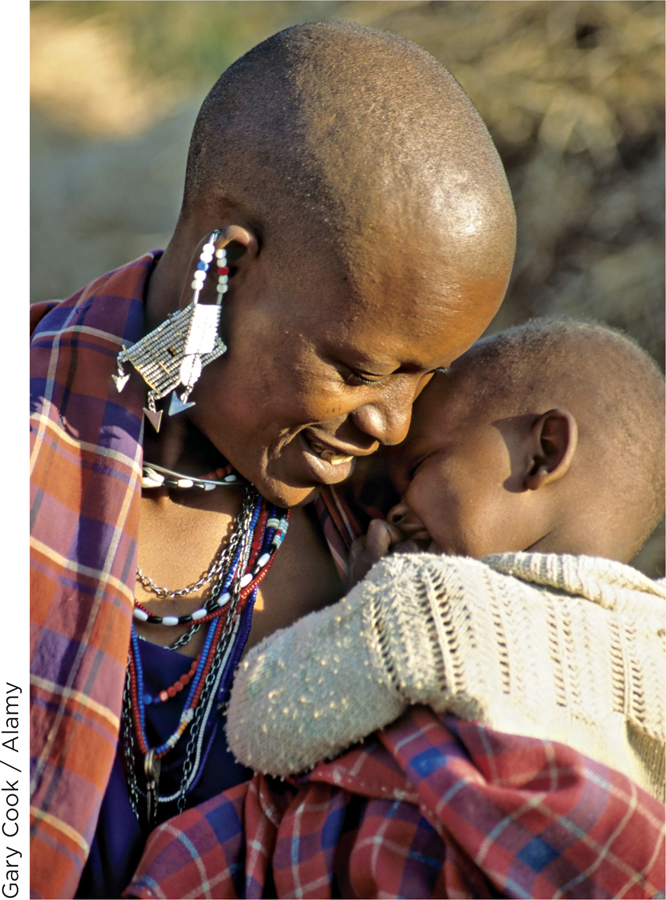

ATTACHMENT. Macaque monkeys are not the only primates for whom parental bonds are critical to social development. The same holds true for humans. We develop particularly slowly; a newborn monkey can move around independently within days of birth, but a human infant takes months to become mobile (Hayes, 1994). This enhances the importance, for human children, of parent–

Attachment is a strong emotional bond between two people, especially a child and a caretaker, such as a parent. According to the attachment theory of British psychologist John Bowlby, bonds of attachment between parent and child have a lifelong impact on the child (1969, 1988).

How could early-

Not all parent–

Different attachment styles have been identified through qualitative research (see Chapter 2). Mary Ainsworth (1967; Ainsworth et al., 1978) observed parent–

Secure attachment: Securely attached infants have a positive relationship with their mother. The mother comforts the child when he or she is distressed, and the child complies with the mother’s requests. If separated from the mother, the infant is happy to see her when reunited. Attachment security enables the child to explore the world, knowing that the mother’s comfort is available if problems arise.

Avoidant attachment: Avoidantly attached infants react in a relatively indifferent manner to the parent. If separated from the mother and then reunited, the infant may turn away from contact rather than try to be physically close. The child does not count on the parent as a source of security and comfort.

Anxious-

ambivalent attachment. In anxious- ambivalent attachment, the child experiences conflicting emotions: a desire for closeness with the mother combined with worry and anger toward the parent. If the mother is away and then returns, the child displays ambivalent reactions— desiring closeness, yet expressing anger and resentment.

Which attachment style characterized you as a child?

624

Ainsworth and colleagues then developed a behavioral measure of attachment style called the strange situation paradigm (Ainsworth et al., 1978). In this procedure, the mother and child participate in a structured sequence of events in a laboratory. First, the mother and child spend a few minutes alone in a room. Then a stranger enters. Next, the mother leaves. Subsequently, the stranger leaves and the mother returns to the room. Psychologists observe the child’s responses, especially when the parent returns. Secure infants are those who are easily comforted by the returning parent. Avoidant children look away and move away from the mother. Anxious-

Numerous researchers have related behavioral measures of attachment styles to personality later in life. A meta-

Psychologists also have related attachment styles to styles of behavior in adult romantic relationships (Fraley & Shaver, 2000). They find that some adults are secure in their romantic relationships, others find it hard to get close to romantic partners (i.e., they are avoidant), and still others want to get close yet are anxious about the possibility of being abandoned (they are anxious-

RESILIENCE AND THE CAPACITY FOR CHANGE. Attachment researchers thought that early-

Other evidence, however, shows that many people bounce back from early-

Striking evidence of resilience comes from a study of 200 children in Hawaii who experienced difficult conditions early in life, often due to parental alcoholism or mental illness (Werner, 1993; Werner & Smith, 1982). If the negative effects of such experiences are inevitable and permanent, one would expect all 200 children to display lifelong problems. But instead, many turned out fine. One-

Further evidence of resilience comes from a study of more than 600 adolescents who, in childhood, experienced abuse (either physical or sexual) or neglect (parents not providing food, clothing, and shelter; DuMont, Widom, & Czaja, 2007). In adolescence, almost half (48%) were developing quite well: progressing in school; experiencing normal relationships; and showing no sign of substance abuse, criminal behavior, or psychiatric problems. Stable living conditions contributed to these positive outcomes. Children who lived consistently with the same parent or parents, or in the same foster-

625

Research on social development, then, delivers good news. Social environments can enable people to bounce back from early-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 9

True or False?

- Iel/Z4atOci9nhcC4jVgXEFx/wJ69RLCTz5fVWW7/Dd21JGtOtI6oa/rNfjkKn4y9qDfNTSuo/UkNF6Y+8aBszmdUfnTHlNRBEDB4NSlJ6rfkNkK3J9JwIfXdgg1uyyGebvIFGXhiY52kMoEArQy0SYqQRzgQVKcbFDL62oefWugVFNJsNudFxxioBM=

- ly2kkKybG+Y+LiGIk82t2wv+0TFBxVdHG628p9weI8KUPFPKiKFqT76xJjJqY3Oj3EmXwbqgZvtH5nLlWgHJRTqwh+CLtUv6vAQjKKetfl1Sstd5GUkZzWIdsUF6b4EYMY+RSxTaIA8fqb/jwsuhblkQPG366AORfRm6+gGCWi5djHsyIxKbTGnaoRsgpPM4QrdlysIgrvZ09fSPPXq0s9y2gAPx6mR02kBJuA==

- X8Qlf980a4JW3ygOSjbCuSpOUYnuH+48FFE4ZDAHe8bUW8cXtP+/U8V5AZDL3ycabIMm4aj/WtPlmkzVO+Dz+c5yrgcyoxi30L4kp4QQiuoX5WwpQeSjijOMKWftNPXN+jTMO7nx5TJE0Ih7kZiRNdVBztEWWYiJSzXTN1gln2FufwaLLk4S6KVYtZK/VtOmYu/cODIl7aBMAGFs8ga/nDtNiqW2UmwuCk2C7ydB+926TIa0mSR/+zm4zmAfA7XzxDHU5h+aF95xU8frfNM1Y1CPVVEyved1YNOyKxbHGQ1WpMdSMP6Mej18zjyObycSeUt781chFnxJOeRxTtSrK2EQCHIahB5uDezn3aMEeihuKW89MSWEyQ==

- pd+MAfObtlbxjZ9CN9KgsVuYw88BPfsitw5IlrqDM3R6WGKovAoy2L7EdmyS6qB8NfyaQwpDOR+/iMGaPIuXr6orBj4Sw0LGYODDA5pxmgVEp1A4HYCon2S1rI4pxWTmp2Irun1GwCGRR1odYjH5R2FBXHPqOeieWicSFXJV5mUkqgDo4tCpatBLhCDaqsJdyymQceNpTiE57l26B9eMTiOe5oRpITeq5zyY+lx/npuxFtzDcR3isdkGCRppDiL4C+LimQO8wuQlOVKCQ7mgog==

- c0DH/SEaGI08M/MyuXCsX4NbY4wA8KUe+QBbU3uq89u+VOwI76+/otWX/4E3PLRRwboafcWBa3IdASDHps2tqJrK5IhiJ805okFdPy5vnnGsGYGsscr0wgu202fgR2WO3ZAqbiBEll5Fohx6Xg9YQB1fubwHvSJGTU1hqGhaV0IFxVVKVCuZosmCMo2qCvy0WM9oUXNYCGp1VA/ompYschZVmy9s47Y2vZc8Vj/XcoqUeC/6E/aG6AzqGHkCIbaqr63k33X+YY2qBamX+s+3nfiYZxRMwbfTFWc7jg==

- 2PZh/XzBNDt80tNTNftPq6l7QHyKBZJxERRKV1EdaG01wiNfiO6dAVLlzFg+iNxDdigHXw+yVC2hGjjm0a4Qg9RJ4A9tWUbWCXQXql6+Zm9RlKXFXQrnidDBkB4+QHBeKaLmMuqvK3vjbotznRszfq/NEzrF9HSvNISYnOzTpVJ1i5WYFAM4FJIGZuzOb75Tlwxdw3o6sIiRAhgH6oCOAcy8KTRRtO0XT1yQi+Sf5dVoUKBeh4X5JCsoVdW+2HLAT2hKuZLiSzBCQFIS803c8DVdyso1WACS3gyw7zBX1Xc=

- GqUjWfuKml2kEspEKdla2YRDX47HqkmJbuziGgeBC8tHBhA9eOaHo39YKS1WA4cViho+xGuA4+/OKYTUJhrRQA+z0VVwGFVpfXp+fQEaJVqgQylIS3fYV+6Z00v64ulTfpaPZhFEHYXwtS3u4SwdeB3hjFa9ODBJfUmakcDUoYeFCUjk7ko1f5tWcYGrJsAzB3G0c1iJmubJZqoIff1uQA2mLNuVQAHzKIjRA0E848+vcwOJoD5Lsub84A8rOF9pHTO2OLq4NrY=

Social Settings for Development

Preview Questions

Question

What is a systems view of families? According to a systems view, what parenting style is best for social development?

What is a systems view of families? According to a systems view, what parenting style is best for social development?

How do features of the family environment affect motor development?

How do features of the family environment affect motor development?

How do siblings influence development—

How do siblings influence development—

How do interactions with peers shape personality development?

How do interactions with peers shape personality development?

Can preschool help to combat the negative effects of poverty on personality development?

Can preschool help to combat the negative effects of poverty on personality development?

626

The world’s children develop in widely varying environments. Some live in a high-

Despite this diversity, there are some constants. Most children grow up with one or both parents; many have siblings; virtually all interact with peers; and all inevitably develop within the economic conditions of their family, community, and nation. Let’s examine these settings for social development.

PARENTS AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT. To understand the role of parents in children’s development, it’s important to recognize that families are “systems” (Parke, 2004; Sameroff, 1994; Thelen & Smith, 1994). A system is any collection of people or objects that influence one another. Families are like this. Not only do parents affect their children, but also children affect their parents, siblings influence one another’s development, and the relationship between siblings affects parents (Parke, 2004).

Interactions in the family system make it hard to predict how any one variable will affect the family as a whole. Research on parenting styles illustrates this.

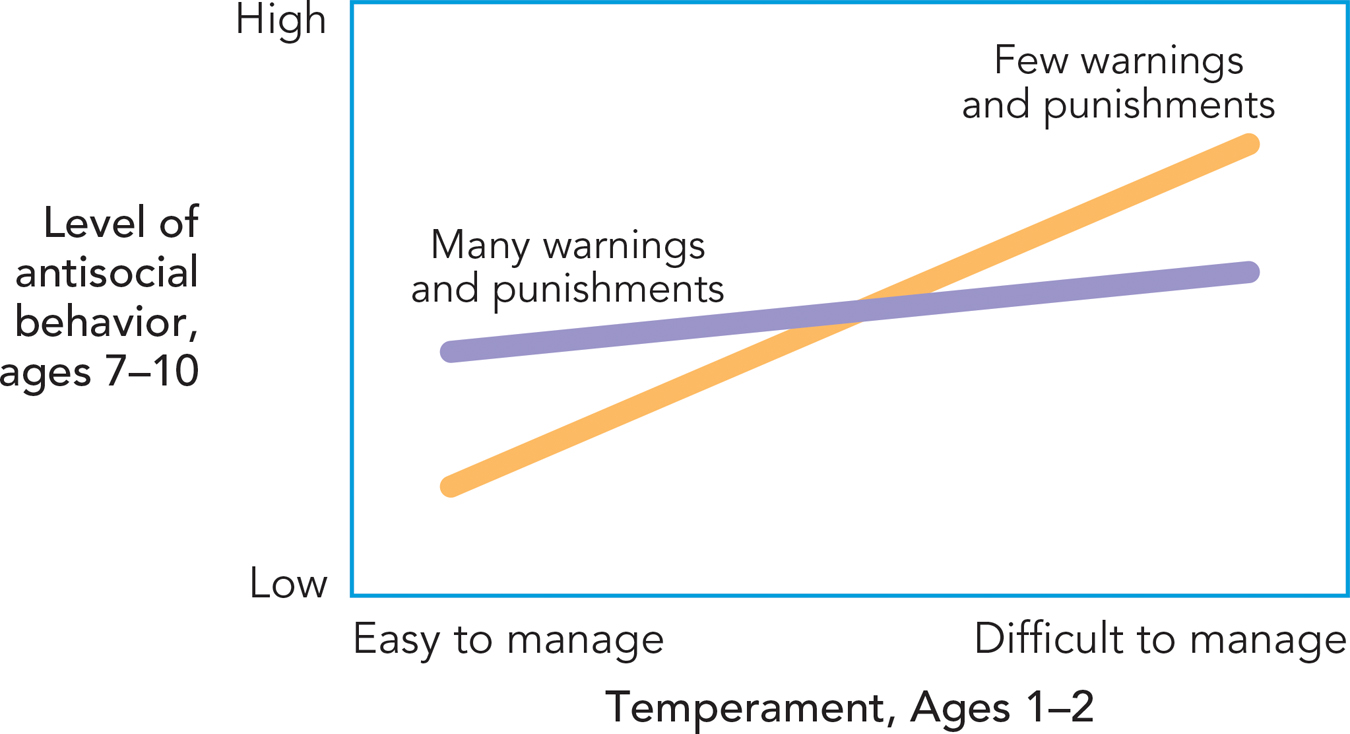

In one longitudinal study—

This result teaches a general lesson about social development. The media often present “facile sound bites about parenting” (Collins et al., 2000, p. 228)—simple reports of what’s best for children in general. But scientific evidence shows there is no single “best way” to parent. Parenting styles have different effects on different children.

PARENTS AND MOTOR DEVELOPMENT. In addition to social development, parenting can affect physical development. Children’s physical skills are shaped not only by inherited biology, but also by experiences in the home (Kopp, 2011). An example of this is children’s motor development, that is, growth in the ability to coordinate muscular movements in order to move one’s body skillfully (Adolph, Karasik, & Tamis-

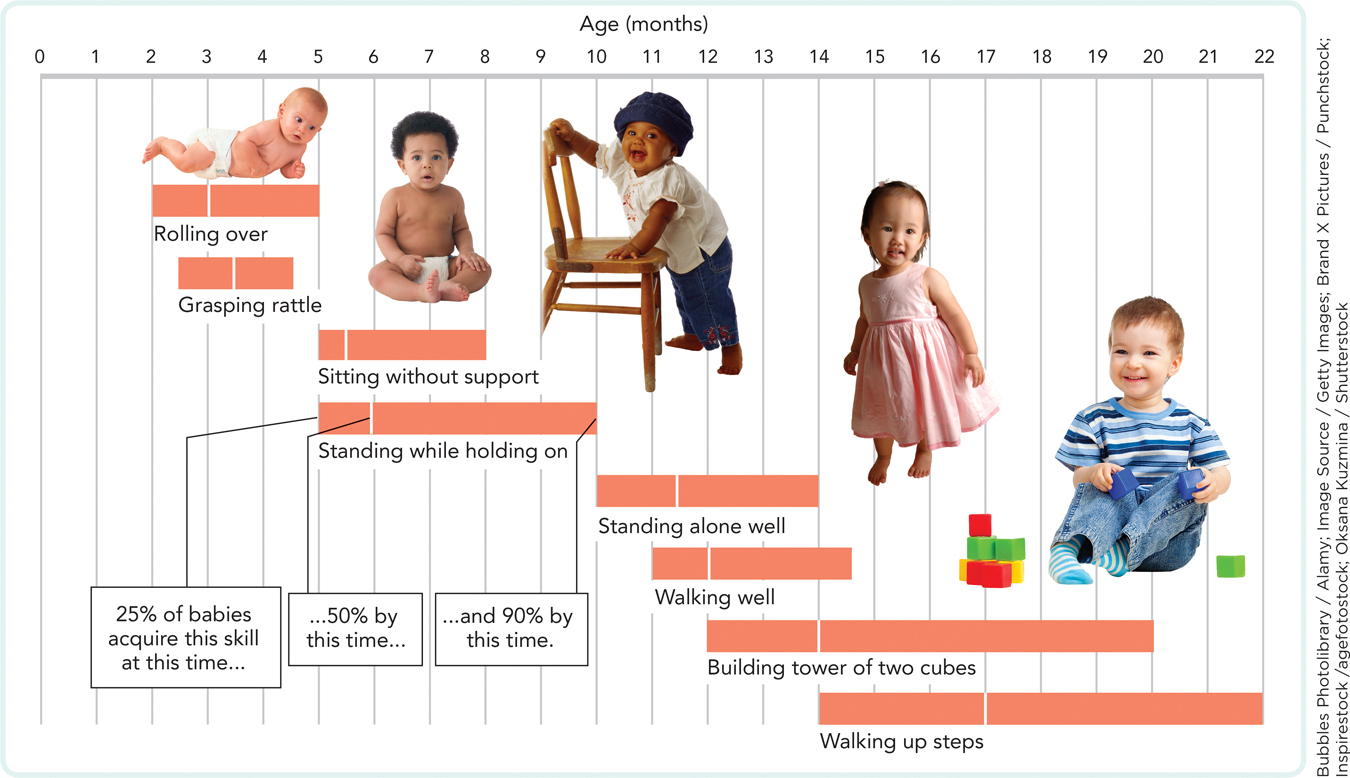

Motor development is marked by a series of “milestones”—significant changes that reflect a child’s growing skill. For most children, motor development milestones occur in the sequence shown in Figure 14.9. Children achieve these milestones through practice. Observations of 12-

The rate at which children develop motor skills is influenced by factors in the family environment. One is socioeconomic status. Children born into wealthier families tend to outperform children from poor households on tests of motor skill (Venetsanou & Kambas, 2010). In wealthier households, children usually have more space to run around (e.g., a backyard) and more interactive toys, which may speed motor development.

627

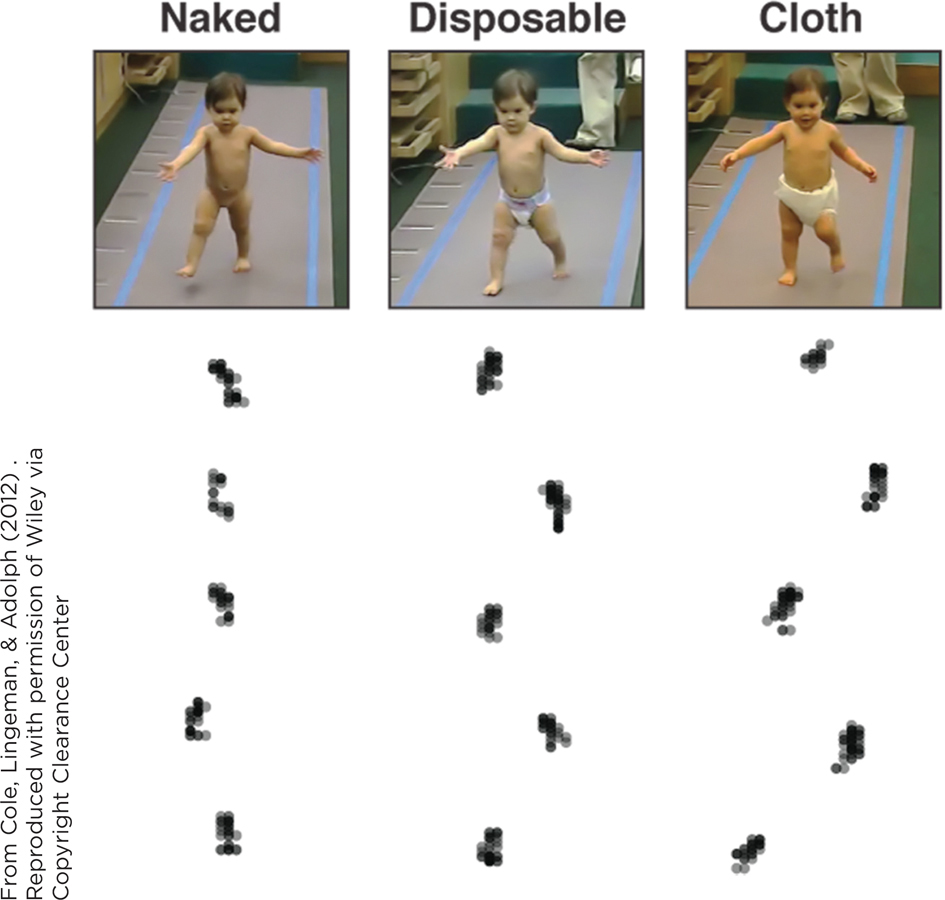

A second factor is more surprising: parental choices about diapers. Researchers observed children’s walking under each of three experimental diaper conditions: (1) no diapers (i.e., naked), (2) disposable diapers, or (3) cloth diapers (Cole, Lingeman, & Adolph, 2012). In each condition, children walked on a pressure-

628

As Cole and colleagues review (2012), parenting styles differ across cultures in ways that affect children’s motor development. In some Caribbean and African cultures, parents frequently prop up their infants rather than letting them lie in cribs. As a result, children in those cultures sit without support at a relatively early age (see Figure 14.9). In some areas of China, infants lie on fine sand that absorbs bodily waste, reducing the need for diapers. This parenting practice reduces freedom of movement, though, delaying the age at which children first sit and walk. Historical evidence indicates that in nineteenth-

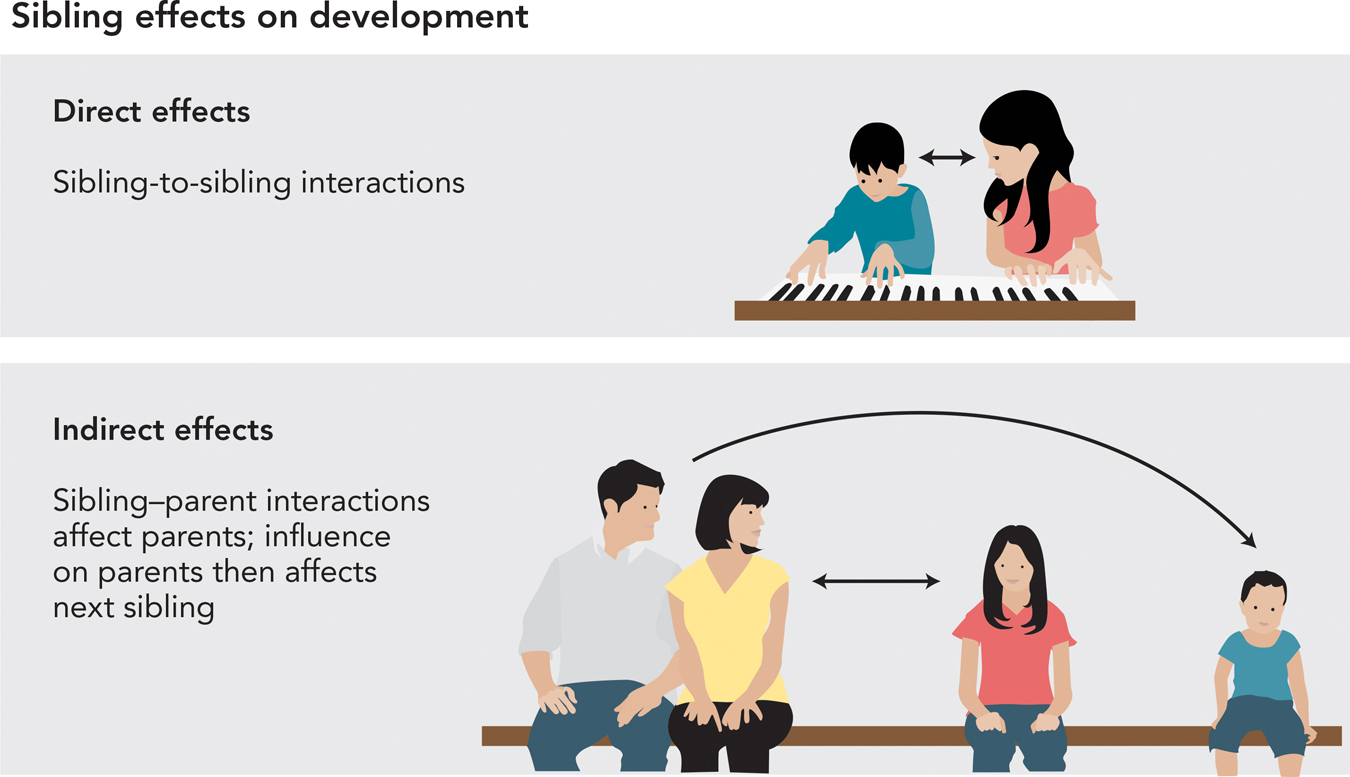

SIBLINGS. Another source of influence on children’s development is siblings. In studying the effects of siblings on one another, researchers distinguish between two kinds of sibling effects: direct and indirect (Brody, 2004; Figure 14.11).

Direct sibling effects involve one-

on- one interactions between siblings. For example, an older sibling may teach skills to a younger one or protect the younger child from emotional distress such as bullying (Brody, 2004). Indirect sibling effects involve the whole family and occur when parent–

child interactions with one sibling affect the parents’ treatment of a second sibling.

Three indirect sibling effects involve (1) parenting skill, (2) birth order, and (3) pecking order.

Parents’ skills change from one child to the next. When raising their first child, parents are learning on-

Birth order effects are differences between the oldest child in the family and later-

629

What is your role or niche in the family? Do the birth order effects hold true in your family’s case?

Pecking order (Conley, 2004) refers to the relative status of children within a family. Many families face scarce resources and must therefore make difficult decisions about allocating family funds. Children judged to be brighter or more socially skilled may get more resources; they rise in the pecking order. Consistent with a pecking-

PEERS. Schoolchildren spend much of their time with peers, that is, boys and girls of their age group. Peers interact in classrooms, on playgrounds, and “virtually” in electronic communication.

Psychologist Judith Rich Harris (1995) explains that peer interactions shape children’s development in two ways: They cause individuals to (1) fit in with, and (2) stand out from, others. The effects are called group assimilation and within-

As I came in … he whispered in a mysterious tone.

“Hush, please don’t make noise, Anton is working!”

“Yes, dear, our Anton is working,” Evgenia Yakovlevna the mother added, making a gesture indicating the door of his room. I went further. Maria Pavlovna, his sister, told me in a subdued voice, “Anton is working now.”

In the next room, in a low voice, Nikolai Pavlovich told me, “Hello, my dear friend. You know, Anton is working now,” he whispered, trying not to be loud. Everyone was afraid to break the silence.

—A visitor describing his arrival at the home of the Russian writer Anton Chekhov, who clearly was at the top of the pecking order (in Parks, 2012)

In group assimilation, a child’s behavior becomes more similar to that of his or her peers. For example, through peer pressure, individuals may feel a need to develop interests, ways of speaking, and styles of dress that match others in the group. If they don’t, they may be teased, mocked, and ultimately rejected by others.

In within-

group differentiation, group members draw distinctions among people in the group. They notice physical and psychological differences and may label them with nicknames (“Skinny,” “Professor,” “Four- Eyes”).

In what ways have you assimilated to your current peer group? In what ways are you differentiated from them?

630

Peer interactions contribute to gender differences in behavior. In childhood and adolescence, girls’ and boys’ interactions with peers differ. For example, girls spend more time conversing with each other, revealing their private thoughts and feelings to close friends and seeking social support. Boys more frequently compete in games in large groups and engage in physical play. In conversation, boys are more likely to talk about their superiority to their peers (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Where do these gender differences come from? In part, they are created by interactions with peers. Researchers measured the degree to which kindergartners played in mixed-

ECONOMIC STATUS. The world’s families differ greatly in wealth. Many can easily provide children with adequate food, shelter, clothing, and education, whereas others struggle to obtain these necessities of life.

Economic status affects psychological development. Greater wealth provides children with opportunities to develop skills that bring success later in life. Poverty presents big disadvantages: fewer opportunities to experience music and the arts, to read and write at home, and to learn about the world beyond one’s own neighborhood (Heckman, 2006). The lack of stimulation may slow development of personal motivation and skills.

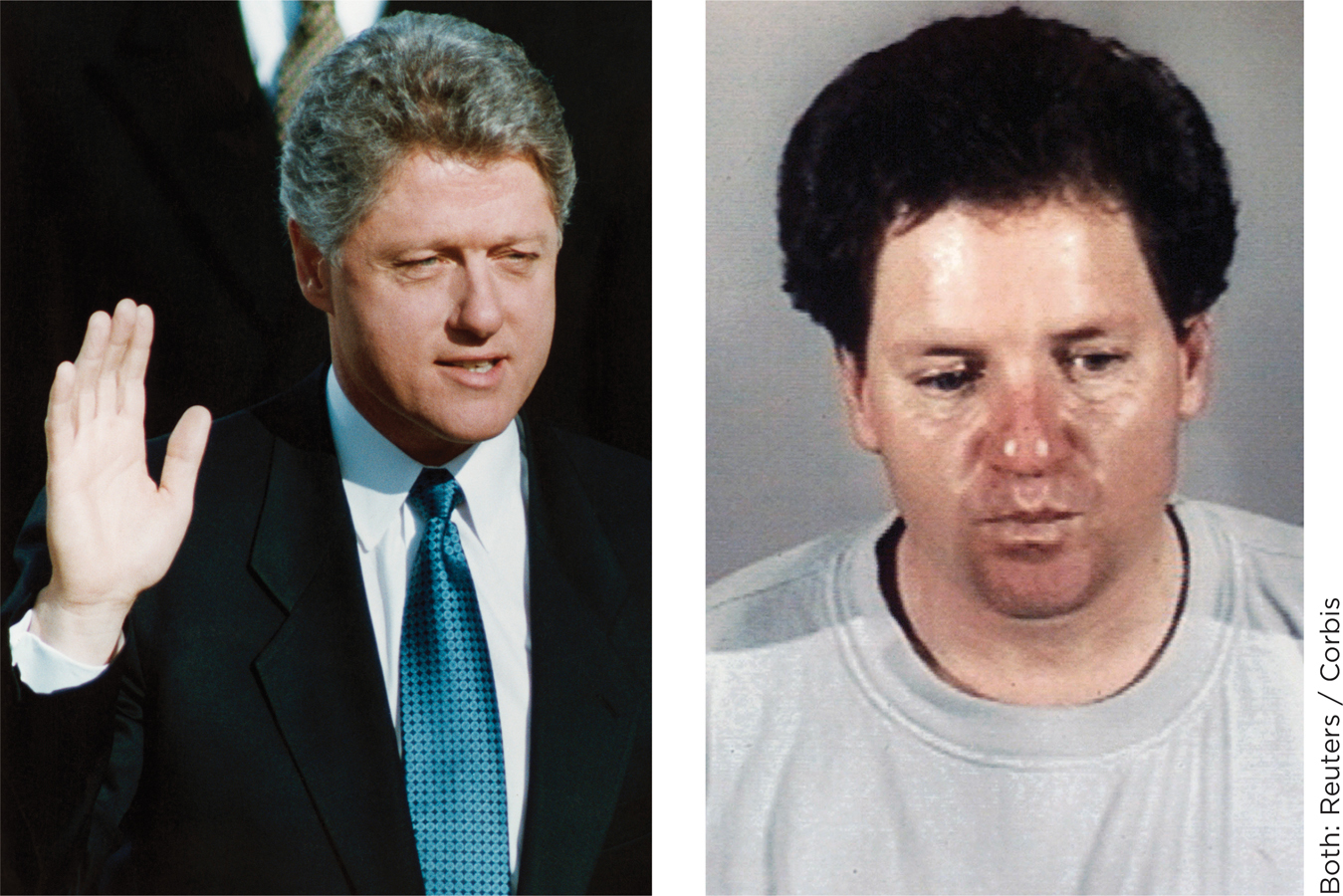

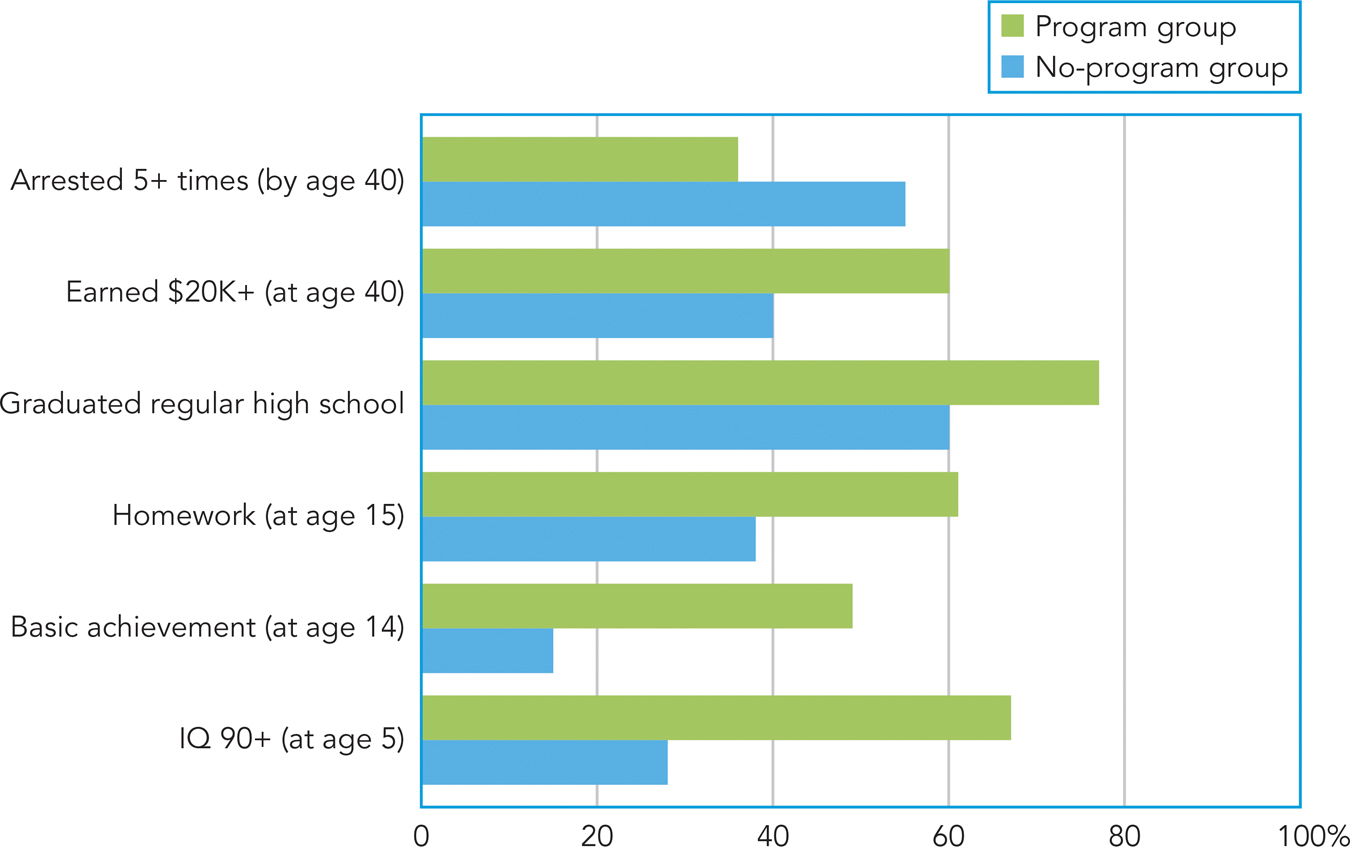

Good news is that interventions can make up for a lack of intellectual stimulation at home. Evidence comes from a large-

More than 100 children aged 3 to 4 from economically disadvantaged African American families took part in the Perry Preschool Study. A subgroup of these children, chosen at random, experienced an enriched, high-

631

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 10

- DTdwOB36YNNg4yU8ow2k2QO11yaQpwiS2zbJ92J5vDIR4FJdkwyqmBNmUkB5PZUDY4KwlBTSCwRN8d1xcL9iMkBYssGTNV6OL/WFlzq7+GaTO25JjrnFwSYYxeoTi2qorxOGBau1AmoTW4fuTDhZV8HEORE+y6+JHzhlC+rmyHBffEnEo46RKe2U0wI=

- gSPF2djdrcf8vuOZf8zTzOo4NBNE5freYC99lWy87dtvB07ZuDnNi1pbEJUVBgMloKT8+ZFQS04anP12E9dgVCCS87hDQ7sayd7gj6Ei05pKtzQfM1O7q/mGa2MUmtPMq+IxCoU2iPZyXp6y62XKjrWcPYWIi6VKgO5ieNQn8WCeGZsWfk3XDNdJMdmQx2vYmK/Lu9L6q4/vCX4E/vmznoRn3dQASuLH0UcDHoIZeDHGj3kFXnmIvQ==

- 6VMcTpDsSSzuyTzLsDqqwcar8LVWGPeudyME3HFokJBKq4YAHHVsu+avHjn9yI5Vb/Y16sIiEgjzmgSuoTaAzI4Ow++HQwQ0mC9NMQ==

- D2/wTY1wB0i471WoghpE5BOKotSoci5qRKxcWRrU5TG/jx4WHB12+Myx+2J4SdbG7CKV/5MPiR+TRKsjlCpMBIQ04207l68KHq3BN91mU10yxDnqCsmciKqnfNElkX49gPCIbiTEzVGjyg2FECL02RR1/UDU4CzZ4R6gr9hkeGKwA4iljiV3ULXZRbsr2jlujevNm1sP2dUZV5BdJ8ZwTRt1BVqp/6101yZdQzkZnNgwsexJS27kvazfT+OiCQo3BcxWtna8M1uHgt6YQSIuvTuuNKq0xtkg4I0gqnZSvHUL6oml184h5EcwwCZq0L7sXwqjb+dNCrBVAaqoF/uqBRQriZj/cKciw8IwA/EySXR9GCg1xC/NsQuWJac38mNvq36/aMThAIQE/SxBP0v73vuDoWkvXEYOjSIDp67Wac6AOe5gCOcRTAPz+78v1nBa

- uma6CkVhG6D/j3AIjHq/uqzTHuq7P/YCwEaN4q143l9ybiFZCrV3E3iWlGmVnZL557TFAUV/uOidPOCRid2e/89zv7Vi7aoUFay7IKZLheRxpOM2p2BXK9Z+55x9p4nvn4Jbtv/vRc/s91aoqpkAvCfXFC4AoQcWkJ+3tIq//d44xlkvJWEx64q2AwBK0blu00fe8bEDvxSkVANo2Kr61zWyn61uoJVlNKNYrXH0hqzIFoXcqccfikydf6GCFK/dl4vrNCP0DHu74QdK1F3/DzQp7VKaEIRh7bwr//xcCqfPwC6SHqn8CdUYW7qmnIK78Rlb7QTXoTulDN/H5Yj/Pp0kgR6qKH1G2HkjQA==

a. Aggressiveness and delinquency were lowest among children whose temperament matched parenting style; easy-to-manage children benefited more from parenting that was laid back; and difficult-to-manage children benefited more from parenting that was strict. b. Five findings were cited in the text: 1. Children who grew up in wealthy households outperformed those of poor households in tests of motor skills, because they had more room in which to move and more interactive toys; 2. diapers (especially cloth ones) impair walking; 3. in some Caribbean and African cultures, parents’ practice of propping up their children rather than laying them down in a crib causes the children to be able to sit up very early in life; 4. in some areas of China, parents sit their children on sand, which absorbs bodily waste, but also reduces freedom of movement, thereby delaying development; 5. in nineteenth-century America, children moved less than those of the twenty-first century because they wore gowns that impeded their movement. c. Pecking order is an indirect effect because it is the parents’ decision to allocate resources to one sibling that affects the share another sibling will receive; the siblings thus do not directly influence one another. d. She would be more typically feminine if she had grown up interacting in same-sex groups because it is in that context where she would have learned behaviors appropriate for her gender. e. By age 40, children who received the enriched education earned more money, were more likely to graduate from high school, and were less likely to be arrested.

The Development of Self-Concept

Preview Questions

Question

How do children acquire a sense of self? How do these self-

How do children acquire a sense of self? How do these self-

How does self-

How does self-

Why doesn’t everybody have the same level of self-

Why doesn’t everybody have the same level of self-

What skill do we need in order to exert self-

What skill do we need in order to exert self-

Does the ability to delay gratification in childhood predict anything important?

Does the ability to delay gratification in childhood predict anything important?

632

CONNECTING TO CONSCIOUSNESS AND BRAIN SYSTEMS

“Tell me about yourself.” It’s easy; you have a well-

In studying self-

FACTS ABOUT THE SELF: SELF-

Developmental psychologists try to answer two questions about self-

Schoolchildren take classes on reading and writing, not on “the self.” So where do they get their sense of self? A major source of information is the opinions and actions of others. Other people are like mirrors (Cooley, 1902): They reflect back to you information about yourself. Input from other people—

The way in which self-

“I’m 3 years old and I live in a big house with my mother and father and my brother, Jason, and my sister, Lisa. I have blue eyes and a kitty that is orange. … I like pizza and I have a nice teacher at preschool. I can count up to 100, want to hear me?”

“I have a lot of friends, in my neighborhood, at school, and at my church. I’m good at schoolwork, I know my words, and letters, and my numbers. … I can throw a ball real far, I’m going to be on some kind of team when I’m older. I can do lots of stuff real good. … My parents are real proud of me when I do good at things. It makes me really happy and excited when they watch me!”

“I’m in fourth grade this year, and I’m pretty popular, at least with the girls. That’s because I’m nice to people and helpful and can keep secrets. Mostly I am nice to my friends, although if I get in a bad mood I sometimes say something that can be a little mean. I try to control my temper, but when I don’t, I’m ashamed of myself. … Even though I’m not doing well in [math and science] … I still like myself as a person … how I look and how popular I am are more important.”

—from Harter (1999, pp. 37, 41, 48)

As you can see, self-

633

FEELINGS ABOUT THE SELF: SELF-

Self-

Self-

In what areas of your life is your self-

Individuals differ in self-

Another influence is parenting style. A classic study (Coopersmith, 1967) identified two aspects of parenting that predict self-

Some factors have surprisingly little influence on self-

MASTERY OVER BEHAVIOR: SELF-

634

As an infant, however, you were unable to stifle your laughter, control your eating, or work toward long-

Children’s ability to control their emotions and behavior rests, to a large degree, on a mental ability known as cognitive control. Cognitive control is the ability to suppress emotions and impulsive behaviors that are undesired or inappropriate (Casey et al., 2011). By concentrating attention on a task at hand, people can avoid distractions and maintain control over their impulses. This ability changes with age; older children are better able to focus their attention on tasks than are younger ones (Rothbart, Posner, & Kieras, 2006). When asked to pay attention to one aspect of images on a computer screen (the type of animal that an image depicted) while ignoring another aspect (the location of the image on the screen), 3-

How easily are you able to control your attention right now in spite of distractions in your environment?

Self-

CONNECTING TO MENTAL SYSTEMS AND BRAIN MECHANISMS IN SELF-CONTROL

635

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 11

True or False?

- Goc1evfiz00S/hf83NIrnPEYzUMmsHtkwhamAceRZtsb02zeNFrxqVUG+VdxffCfN23BDdMQXhksdglR6Er3ZPmERcVINkGXNQ+GRQ6gHopgrgdSX/1nAAyojy0YfY5CLRRlbrsOtY95707f/GYqBxl/X6L9To8xQRdK/Wvqiyf9jsbetuyODmNN3D0tgIdEPCEQt5nzIPPdv8O4r9C5dqIHGDusz33IBQxJ2g4bW+s+7SiNvcp4dGqpt0VesEZTSIo0q1SeRzv5vI8ra7hRv8Kb+Hw4Z+XNgOh/xmlYCg9QQ6Q6CFH/9no4tXYuJ1YQIlMwtFW1GkLmRVz04PJl5QLYoGLY/8sKqug9es0IRpGdBgZkuK+tZx5bLXds8K6O

- AR0f1WzMjkzqB+LRKO6QfPllqOt8AMruXs0HgJ78a5k8i53+daqy+4eF6qL+Pjh88EiHVwIKd8nDHVlCY2VzvRW1aqUTKIBY9OXIgGugVceg4s34zPwAefYNwZCjTgRVexesal/xDsDp+L9iRrzxN7qjyZP+uf/v2B4CQl5Qa1RSVDqOtiTgm0IKqJRR/KypJA+tpm4hvHFhvNBTcqEMtwrAnc9XltvTmkVPhgujW0j2WwWj

- I6CUydzTprEsgvTNjwisAkoxekMr2sFvb+9HT7wKm7eVeoC19kWCyifBiuO/x8ODJvwsgd1HcSMN+DyfQqGdGGGFN97XfgHz93whT4/3VJFRJqJNHlvMz39K5kKNatTp3wfh17A3iw7WSTm8DJ80ltEUFVoOgeKehlIos/2JXyTMTXPAsPxHXz36EgnA9py4JYg70hQPeV8=

- /JwMXmMrELUP54/1Kc6Q/wRqYkWBLnVm81WPElgvBRjCYzDS4HLhiZl6J1thXwiQR/AdRLKySX/GBF5N9jVaqgY91v4iXkX/LnKXH/A82J2sYnSZGnz6AHtg6BUPcrnGJSUk+2i4STiRsI44pEs6GAaldx+kbOFg1xonZb90SEslifbZUSguyo1L1QmyjMPrq4GqGT9kc2FaUepCMMgy7o1kE8LLlp8VTFK9sRFhJAOQCEt/epmFYdyzXsCimT+jjPDaOapZH4y/lrrtKxSeFT75L29eQiKzCrvHeCXvRa06IRYdsxJVRepRsgST9tKihVAK5PdEOc8gusjoN38+4IFt4+mClzhO4zvsQw==

- L8P0GjO8ixXoXHayAXaIhpu2vM1gHIZXvwm87zCk4TpgghW0lJChXmSll7dA0rph1HitwgKaL6UcocudZU9RxsrslV6PCSA4nMe2cGbcIiynOClofcPg2domvmmAVp/kmJDEzDtX95CQnuVTnjRkDNxW0UoHfoSJflYlnRbhJVpJspWBCSIFCKEXJKrnBT+vchIW+4Xae2wdD+wU7VuAFsUPzeEGHk7FBcJZcwe+y2u981v3A0Q5hsabMSPY5vY8jwBV2KAe3WkaA4mhnbY1ePm1KSsc9zn/

- nJ5x0NcJR0fIT7mywVNSpYkhhPEP2sM5AaiWdSNco2gI7uF4mce5dYvVaJHrQnGG9Rqvg/98kUNYcpw/yMn3Uvdiz3B/e08VN4+Yisjh5LZ8RByHb+lOFgvkyr8MWG/dnehXrTL6srPjL4Q1urFTVDbyijU/PI+7FfL7QsOxjL4ozFeH7CjehSmMmCl/1sZAXA1c0sLftxHIfv2sZ23BxoM/0IcrPmAqiyAk36/Mg/l79533JVpHBQecVyr6p6xOoCWCYy2vmGlghyEXvNSYJg==

- rclVvohb13LC7/pnFdHoLSVZE3W1dJlvlJtfUTfYf1+5INnLhoK+9T7S5QtHdcjrehIVdtLD62+foWxCvAHH6+m9kkrrDrtV+o87UpuUO9hyF8WjDavrEl402p9Y0cqrRmJgMpnHRd1UuGuEVVuCy96weSmZ6zfPYcEvHlUs6HxZHTw8e8WI69GsNm0tarfyul7kUsIgv8Nu1CiVKQNrmEa+Z3/jwj4P4/M6HHlkBbJQ25AiVRPf2h6pncv8oFxG

TRY THIS!

Before moving to the next section of this chapter (on social development in adolescence and adulthood), go to www.pmbpsychology.com for the Chapter 14 Try This! activity. While doing it, ask yourself: How might the research activity relate to the topic of social development in adolescence and adulthood? ![]()