14.3 Social Development Across the Life Span

Thus far in this chapter, we have focused most of our attention on childhood. Let’s now look at social development across the span of life, starting with adolescence.

Adolescence

Preview Questions

Question

How do biology and social environment interact to influence behavior during puberty?

How do biology and social environment interact to influence behavior during puberty?

What are four ways in which adolescents cope with the challenge of establishing a personal identity?

What are four ways in which adolescents cope with the challenge of establishing a personal identity?

Adolescence is the period between childhood and adulthood. Societies differ in beliefs about its exact time span (Arnett & Taber, 1994). However, adolescence generally is thought to begin around ages 12 to 13 and to run throughout the teenage years.

Adolescence features numerous changes: physical, emotional, social, intellectual. Think back to your own experience. In adolescence, you suddenly did not look like a child anymore. Your peer groups changed when you entered middle and high school. Adults expected you to be more self-

Adolescence poses two big psychological challenges. One stems from the biological changes of puberty. Another is the psychological challenge of establishing a personal identity.

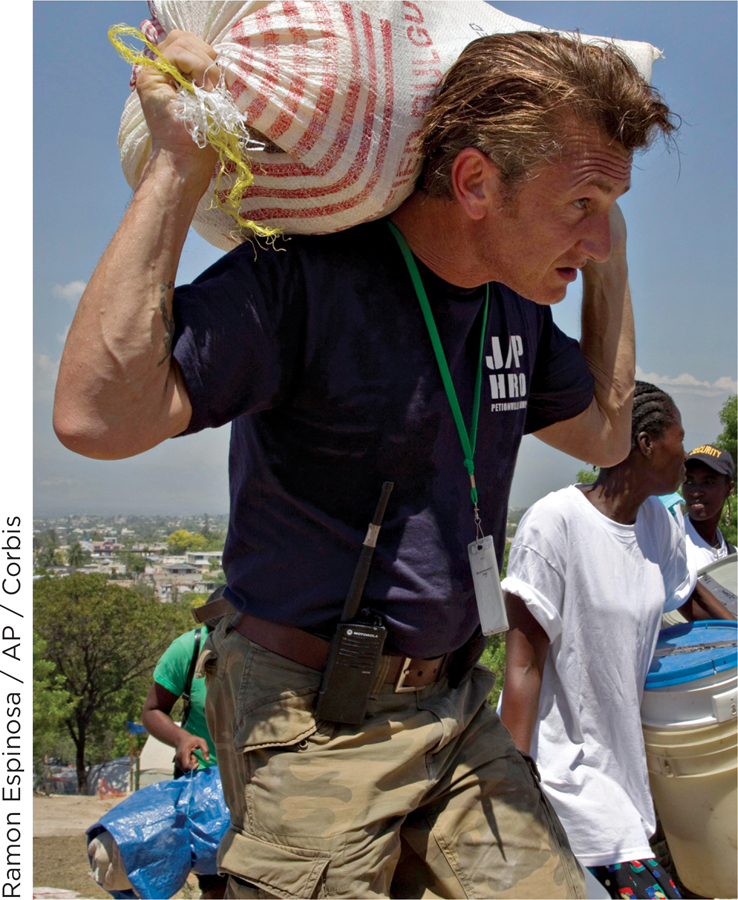

PUBERTY. Puberty is the time when a child reaches sexual maturity. Girls and boys experience physical changes that transform them into women and men who are biologically capable of reproduction (Figure 14.13).

Behavioral changes accompany the biological ones. Compared with children, adolescents are more likely to have conflicts with parents (Laursen, Coy, & Collins, 1998; Paikoff & Brooks-

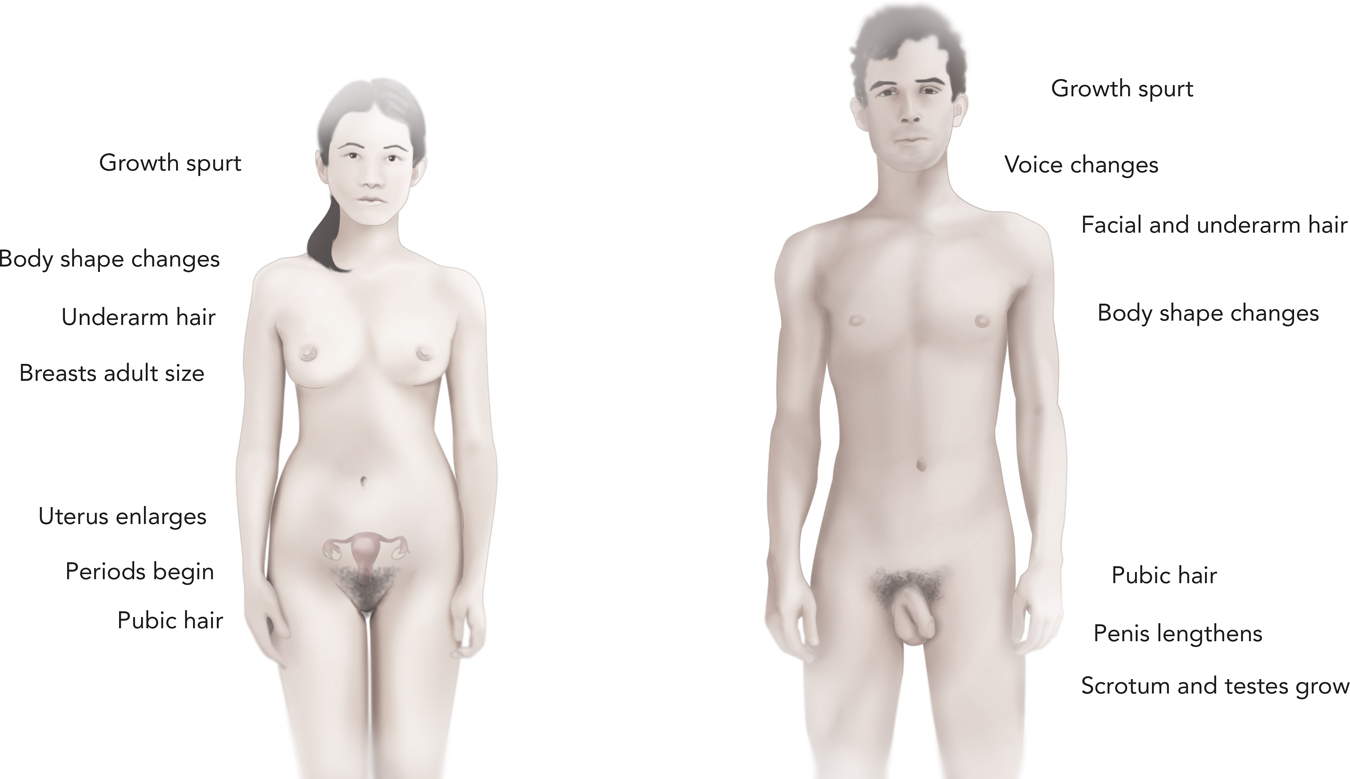

How do the biological and behavioral changes relate to one another? There are two theoretical possibilities (Figure 14.14):

Biological model. A biological model says that changes in biology cause changes in behavior. Because all normally developing adolescents experience physical changes, this model suggests that changes in behavior during adolescence are inevitable; all adolescents should, for example, show increased antisocial behavior during the adolescent years, according to the biological model.

figure 14.14 Models of biological and social development Different conceptual models guide research on biology and social development. In a biological model, biological factors directly produce behavioral effects. In a biopsychosocial model, the effects of biology interact with the environment. Biological factors may shape social experiences that, in turn, shape social behavior.Page 637

figure 14.14 Models of biological and social development Different conceptual models guide research on biology and social development. In a biological model, biological factors directly produce behavioral effects. In a biopsychosocial model, the effects of biology interact with the environment. Biological factors may shape social experiences that, in turn, shape social behavior.Page 637Biopsychosocial model. A biopsychosocial model says that the impact of biology on behavior depends on adolescents’ social experiences. Social behavior, then, reflects an interaction between the biologically changing person and the social environment, which reacts to those changes. Behavioral changes, according to this model, are not inevitable.

How can you tell which model is correct? It’s not easy; it requires longitudinal research that measures both biological changes and social environments. One example of such work is research on antisocial behavior among girls who reached puberty at different ages, by Swedish psychologist David Magnusson (1992).

If the biological model (Figure 14.14) were correct, then among all girls, those who reach puberty at a relatively young age should differ behaviorally from others. Biology should drive behavior. This, however, is not what Magnusson found. Rather, biological changes affected behavior only among some girls, and the effects depended on the social environment. A key social factor was peer groups. Some (but not all) early-

Results therefore support a biopsychosocial model. Biological changes can create social changes that, in turn, affect the development of behavior.

IDENTITY. Suppose you were asked to describe yourself: your personal history, social roles, and goals in life. Your answer would indicate your identity. In the study of social development, identity is people’s overall understanding of themselves, their role in society, their strengths and weaknesses, their history, and their future potential.

Questions about identity strongly arise in adolescence (Erikson, 1959; see Chapter 13). Many adolescents begin to ask: What is my true personality? What are my strengths and limitations? What will I do in my future? In essence: Who am I?

People differ in whether and how they think about identity, and in how long they take to decide on a life path. Some find an answer quickly and commit themselves to a role in life. Others experience prolonged doubt and confusion. Still others give identity questions little thought at all. The psychologist James Marcia (1980) summarizes these differences by suggesting four different identity statuses, that is, different approaches to coping with the challenge of establishing a personal identity. (Marcia’s efforts capitalize on earlier analyses of personal development by Erik Erikson; see Chapter 13.)

Identity achievement: People who have deeply contemplated life options, chosen a career path, and are firmly committed to it thanks to deep personal values have the status identity achievement. For example, someone who has decided to be a doctor because she values the alleviation of people’s physical suffering has reached identity achievement status.

Foreclosure: People who know their role in life and prospective future occupation, but who feel these were imposed on them by others, have the identity status foreclosure. The term means that others, by imposing their values and expectations, have foreclosed one’s opportunity to explore novel life paths. Foreclosure can reduce people’s commitment to their activities.

Identity diffusion: People who feel directionless, with no firm sense of where they’re headed in life, have the status identity diffusion. These individuals generally have not given deep thought to their personal values or goals; they just know that they don’t know exactly where they’re headed in life.

Page 638Moratorium: Some people contemplate many life options but are unable to commit to any one set of goals. These people have an identity status called moratorium. The word refers to a suspension of activity. When people can’t commit to a life path, their lives are, in a sense, “suspended” until they can settle on a path to pursue. Moratorium status can cause people to experience anxiety about themselves and their future.

Which identity status describes you?

People with different identity statuses differ in their behavior—

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 12

In Magnusson’s research, what was the social experience that led early-

Question 13

Match the identity status on the left with the statement that illustrates it on the right.

1. Achievement 2. Foreclosure 3. Diffusion 4. Moratorium | “I had so many ideas for what to do as a career, but I got overwhelmed and am now just working a part- “I have so many interests, but no idea which one I should pursue. I hardly even know who I am or what I’m good at.” “It became clear to me that the best way for me to help people out of poverty was to use my talents to become a teacher.” “My parents always valued education, so I figured I might as well become a teacher to make them happy.” |

CULTURAL OPPORTUNITIES

Ethnic and Racial Identity

We live in a “globalized” world. You can access a worldwide web of information. Many people work for multinational corporations. Movies and TV shows have an international reach; The Simpsons, for example, is so popular in China that the government once banned it from prime-

How does globalization affect ethnic identity, people’s personal identification with the ethnic group to which they belong? You might expect globalization would reduce it. Criss-

A study of African American, Asian American, European American, and Latino American high school students in Southern California (Phinney, 1989) showed that students of this age differ in ethnic identity. The differences corresponded to three stages of identity noted above: diffusion, moratorium, or achieved.

Diffusion: Some students had given little thought to their ethnic identity. “Why do I need to know who was the first black woman to do this or that?” one student said. “I’m just not too interested” (Phinney, 1989, p. 44).

Moratorium: Others gave a lot of thought to their ethnicity, yet still were puzzling over their relation to their ethnic group. “There are a lot of non-

Japanese people around me and it gets pretty confusing to try and decide who I am,” said an Asian American male (Phinney, 1989, p. 44). Identity achieved: A third set of students had a firm sense of ethnic identity. They understood their group and their relation to it. “I have been born Filipino and am born to be Filipino. … I don’t consider myself only Filipino, but also American” (Phinney, 1989, p. 44).

By contrast, European American students (the majority group in this study) “did not show evidence of these stages. … [E]thnicity was not an identity issue to which they could relate” (Phinney, 1989, p. 41, 44). European Americans primarily said they were “American”; their ethnic ancestry generally was not important to their personal identity. Ethnicity is more likely to be a part of your identity if your ethnic group is in the minority.

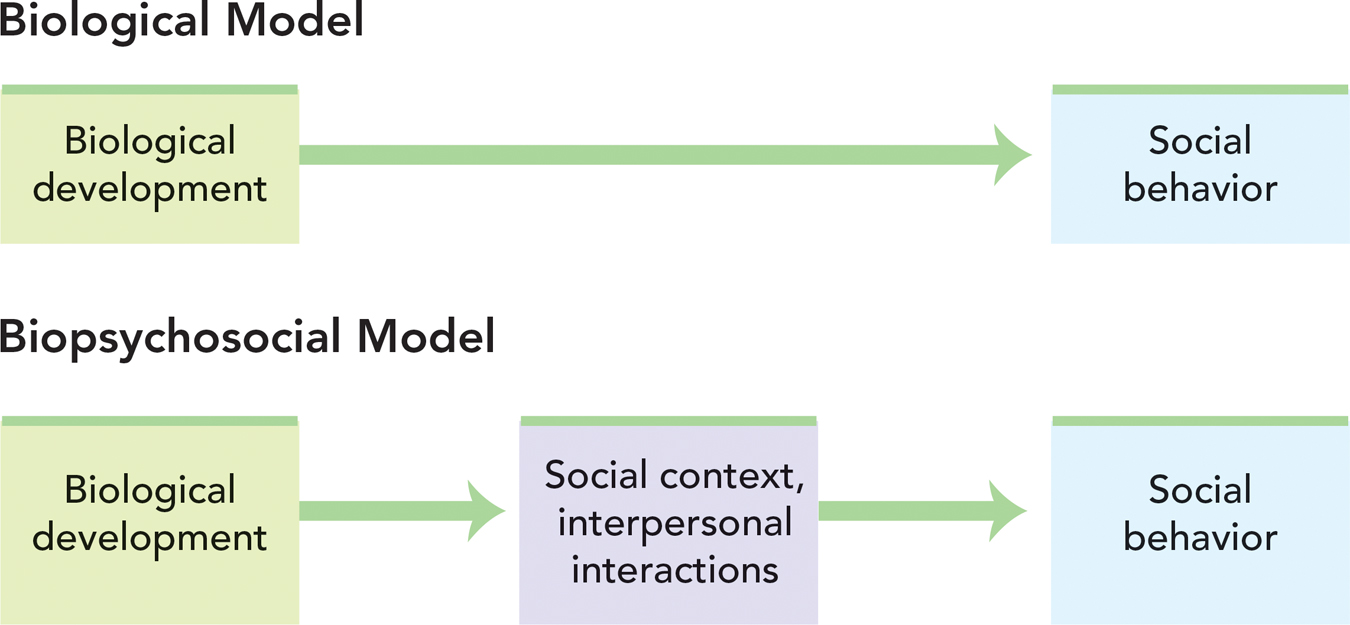

A theory developed by Robert Sellers and colleagues (Sellers et al., 1998; Figure 14.15) explains how the identities of group members differ from one another. These researchers focused on African American racial identity and identified four dimensions of variation:

Salience: Whether individuals judge that their race is relevant to them in a given situation

Centrality: Whether race is self-

defining for a person Regard: Positive or negative feelings about the racial group

Ideology: A person’s beliefs about how members of the group should act

[Sellers, R. M., Smith, M. A., Shelton, J. N., Rowley, S. A., & Chavous, T. M. (1998). Multidimensional model of racial identity: A reconceptualization of African American racial identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2, 18–39, © 1998 by Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc. Reprinted by permission of SAGE Publications.]

Racial identity, then, cannot be reduced to a single quality that is common to all members of a group.

In sum, ethnic and racial identity is complex. One can’t be sure of an individual’s identity beliefs just from knowing the individual’s ethnic group. But one thing we can be sure of is that, despite globalization, ethnic identity is here to stay.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 14

High school students’ ethnic identity corresponded to Marcia’s identity stages. Which stage is exemplified by the following statement? “I speak Chinese at home and English at school. I feel like I’m stuck between two worlds. Sometimes I don’t know who I am.”

Emerging Adulthood

Preview Question

Question

Are 18-

Are 18-

Decades ago, most Americans entered into the work and family life of adulthood soon after adolescence. In the 1950s and 1960s, the average age of first marriage was under 23 for men and 21 for women (Information Please Database®, 2009). But times have changed. Today, the average age of first marriage is more than five years later for both men and women.

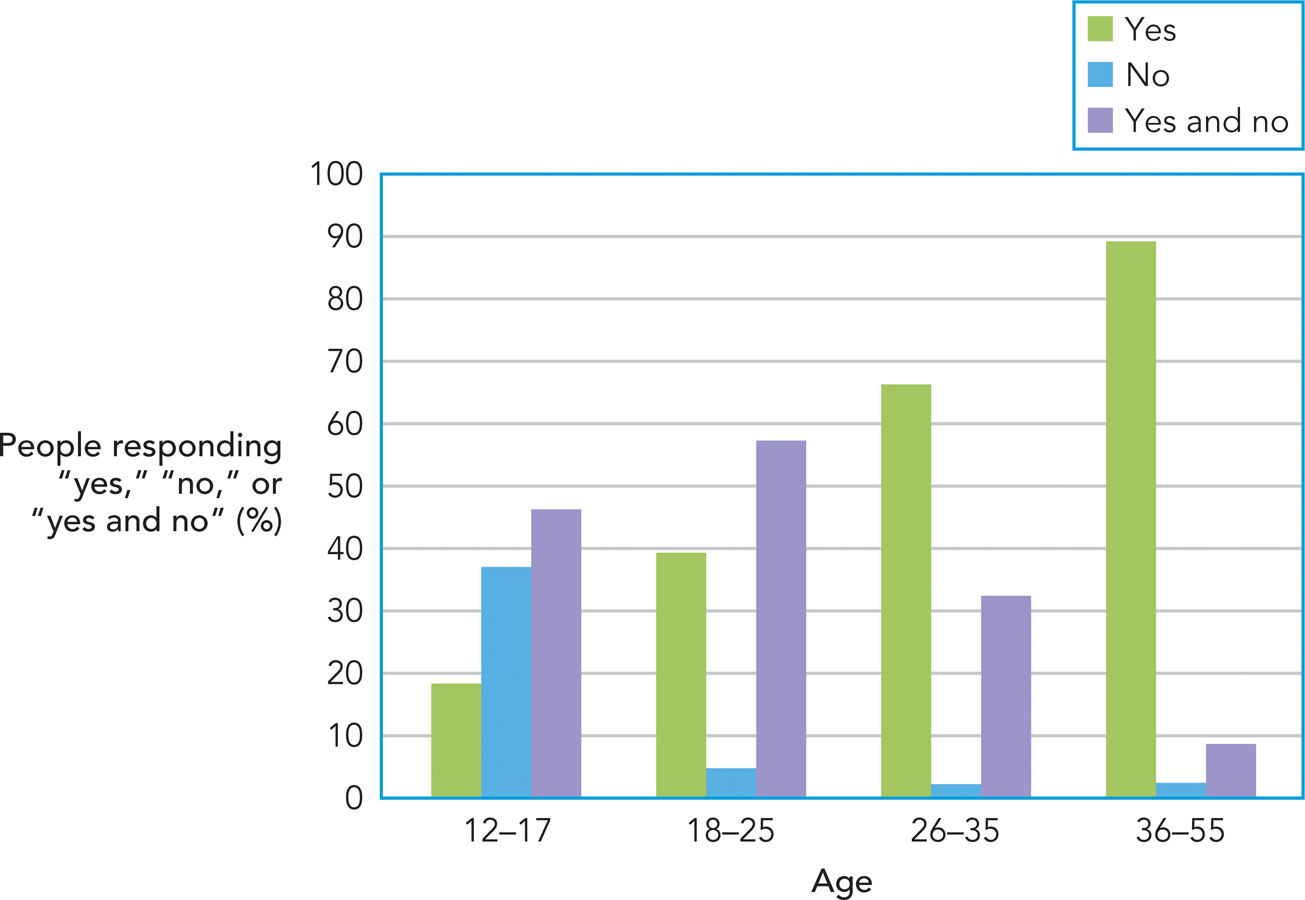

This change creates, for many people in their early 20s, a relatively novel developmental period. The psychologist Jeffrey Arnett (2000) calls it emerging adulthood. Emerging adulthood is a period of life in the very late teen years and early 20s (roughly ages 18 to 25). It is experienced by people who, on the one hand, have the rights and psychological independence of adulthood but, on the other, do not yet have the obligations and responsibilities of family life (Arnett, 2000). Surveys show that people experience this period of life as unique. When asked whether they feel like adults, most people do not say yes or no. They say, “Yes and no” (Figure 14.16).

Emerging adulthood is a time of exploration. People may try one job, quit, then try another; move from one city to another; and explore new relationships before settling down into marriage. The relationships of emerging adulthood often are in flux. Research shows that, among emerging adults who experience a relationship break-

Today’s emerging adults allocate time to activities that did not exist in the past: an average of 3½ hours a day on the Internet and 45 minutes a day texting or making phone calls (Coyne, Padilla-

THINK ABOUT IT

When you hear the phrase “stages of human development,” it might sound as if a fixed set of stages has characterized the development of all people, in all times and places, throughout human history. Is that true? Researchers studying emerging adulthood see this stage as a recent development in human history. Might other stages also be relatively new? Hint: The entire concept of adolescence as a life stage that exists prior to adulthood did not develop until about 120 years ago (Kett, 2003).

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 15

Individuals in emerging adulthood have the psychological independence and of adults but not the responsibilities of life.

Midlife Development

Preview Questions

Question

Is a midlife crisis inevitable?

Is a midlife crisis inevitable?

What are some common themes of individuals’ life stories?

What are some common themes of individuals’ life stories?

Some years from now, you’ll be done with school. You might have a job and a family and be settled into “the afternoon of life,” the midlife years. Or maybe you’re already there.

Biologically, midlife is not sharply defined. Culture shapes people’s thoughts about this life period. In fact, the entire concept of “middle age” is a cultural construction (Shweder, 1998); nothing about human biology delineates an exact middle-

MIDLIFE CRISIS? Fill in the blank: midlife _______. Many people would say “crisis.” A stereotype is that midlifers become overwhelmed with their loss of youth, experience a crisis, and do surprising things: quit their job, join a new religion, buy a flashy sports car.

Research findings challenge this stereotype. Most midlife adults do not experience a sudden crisis and drastically change their lifestyle (Wethington, Kessler, & Pixley, 2004). Midlifers do “take stock” of their lives—

Similarly, some midlife events have less psychological impact than you might guess. Consider, for example, menopause, the end of female reproductive fertility, which generally occurs around age 50. Is menopause a psychologically negative event because it signals advancing age? Interviews with women suggest not; their “attitudes toward menopause ranged from neutral to positive” (Sommer et al., 1999, p. 871). So many women live such busy lives that menopause isn’t a major event. For example, among African American women, who had the most positive attitudes toward this life transition, “menopause seemed a minor stressor,” especially compared with others, such as “the consequences of racism they had experienced throughout their lives” (Sommer et al., 1999, p. 872).

LIFE STORIES AT MIDLIFE. By early adulthood, people usually have developed a life story

Everyone’s life story is unique, yet life stories have common themes. Two are generativity and redemption:

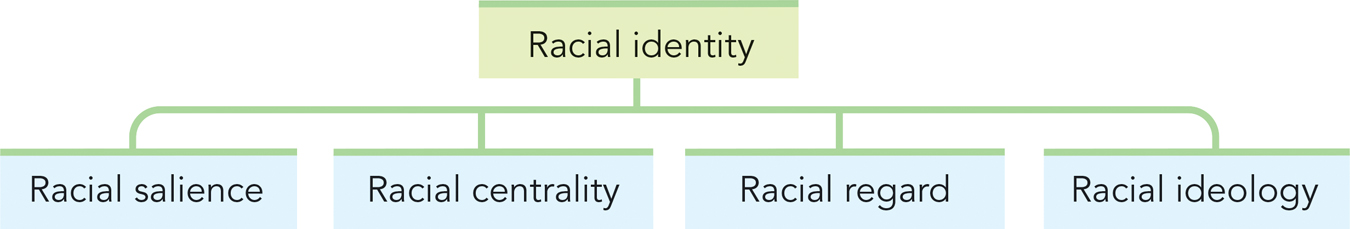

Generativity is a concern for future generations (Erikson, 1963). Some adults see themselves as contributing to the welfare of future generations, whereas others’ stories lament their failure to contribute anything of lasting value.

Page 642Redemption is a theme in which life is transformed when a personal crisis is overcome (McAdams, 2006). With the crisis behind them, people are poised to contribute to the world.

Researchers have studied these themes by asking people to tell stories highlighting “turning points” in their life and to describe what they personally are striving for (McAdams et al., 2001). Adults whose life stories included themes of generativity and redemption were more well-

Midlife, then, is not a time of inevitable crisis. Midlifers assess their lives and experience greater psychological well-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 16

True or False?

Consistent with the stereotype, most individuals eventually do experience a midlife crisis.

A. B. Consistent with the stereotype, most women perceive menopause to be an overwhelmingly negative major life event.

A. B. People whose life stories include themes of generativity and redemption tend to be more well adjusted.

A. B.