15.2 What “Counts” as a Psychological Disorder?

Practicing psychologists face the question you encountered in this chapter’s opening: Who is, and is not, suffering from a psychological disorder? Many people feel sad or anxious. Many display behavior that’s “quirky.” Are they all suffering from a mental disorder?

In principle, the definition of “psychological disorders”—prolonged experiences of unusual psychological distress or poor psychological functioning—

That question has no simple answer. There are no sharp boundaries of “normality” and “abnormality” (McNally, 2011). Even highly unusual behavior may not signal a psychological disorder. To see this, let’s return to the three cases in the chapter opening: the anxious girl, babbling man, and political activist working to improve the welfare of hospitalized patients.

Psychological Disorder or Normal Reaction to the Environment?

Preview Question

Question

What caution must we exercise when evaluating unusual behavior?

What caution must we exercise when evaluating unusual behavior?

What did you think of the people described in the opening of this chapter? The girl seemed weird: constantly anxious and jumping into her father’s bed every night. The man seemed weirder: babbling incoherently and breaking into tears. The woman, though, seemed quite normal: working diligently to benefit people in need. Now let’s learn more about them.

The anxious teenager is Anne Frank, a Jewish girl living in Amsterdam when it was occupied by Nazi Germany during World War II. The Frank family needed to hide from the Nazis; if found, they would be arrested and likely killed. (Ultimately, this is exactly what happened; Anne Frank died in a Nazi concentration camp.) The Franks went into seclusion, hiding for years in a secret apartment hidden behind an office. Throughout this period, the family lived under constant threat of detection. No wonder she was so anxious! As her remarkable diary (Frank, 1952) shows, Anne Frank was not psychologically disordered. Her extreme anxiety was a perfectly normal reaction to an extremely disordered environment. The problem lay not in Anne Frank, but in the war-

We have for too long been taught that the sight of a man speaking to himself is a sign of eccentricity or madness.

—Teju Cole (2011, p. 5)

The babbling man is a Pentecostal Christian (Higley, 2007). Pentecostals believe in the power of speaking in tongues, an ability that they trace back to a New Testament event in which the Holy Spirit gave the Disciples of Christ the power to speak in multiple languages (Macchia, 2006). To Pentecostals, the man’s speaking is perfectly normal—

What is a behavior that you engaged in today that, out of context, might appear unusual?

In both cases, Anne Frank and the Pentecostal, social context is critical. The behavior seems “weird.” You might think the person is “crazy.” But when you understand the context in which the person lives, you recognize that the behavior was a normal response to a situation with which you were unfamiliar.

What about the third case from the chapter opening, that of the political activist? She seemed normal. Yet, soon after her newspaper article appeared, government officials “forcibly detained [her] in a psychiatric clinic” (Gee, 2007). The government ran the hospitals she investigated, reportedly felt threatened by her article, and responded to the threat by labeling her “mentally ill.” Her case is not unique. Soon after, Russian government officials labeled a political protestor a “confused and paranoid lunatic” and, similarly, confined him to a mental hospital (Holdsworth, 2008). Doctors claimed that when he was hauled away to the insane asylum, he seemed “stressed … suspicious of others, argumentative and confused.”

“It’s hardly surprising I seemed like that,” the man later noted, “given the circumstances” (Holdsworth, 2008).

Such cases raise a critical question: Who judges that a person is mental ill? People in society differ enormously in power, that is, their degree of influence over social events and others’ lives. Typically, people with greater power judge the mental health or illness of people with less power (Foucault, 1965). Government officials can call protesters “mentally ill” and, in some countries, send them to asylums. Protestors can’t do the same to government officials.

Social and historical factors also affect judgments about mental illness. Behavior that seems normal in one time period can seem abnormal in another. For instance, modern professionals do not view any sexual orientation as disordered—

As these examples make clear, claims that a person is mentally ill must be made cautiously. Sometimes unusual behavior reflects unusual life circumstances. Behavior that appears abnormal in one social or historical setting may seem completely normal in another.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 2

A careful consideration of whether to classify someone as having a mental illness must take into account the in which the unusual behavior occurs.

Classifying Disorders

Preview Questions

Question

What is the major tool mental health professionals use to diagnose and classify psychological problems?

What is the major tool mental health professionals use to diagnose and classify psychological problems?

What are some criticisms of the major tool mental health professionals use to diagnose and classify psychological problems?

What are some criticisms of the major tool mental health professionals use to diagnose and classify psychological problems?

Despite these cautions, there is no question that millions of people the world over suffer from serious psychological disorders. A first step in helping them is to diagnose their disorders, that is, to classify them as being of a certain type. Just as physicians diagnose and classify physical problems as a first step in formulating medical treatment, mental health professionals diagnose and classify psychological problems as a first step in formulating therapy.

THE DIAGNOSTIC AND STATISTICAL MANUAL (DSM). The tool that psychologists use to classify disorders is a book: the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM. The DSM comprehensively lists and organizes the mental disorders identified by health care professionals. Each listing specifies behavioral and emotional responses a person must experience to be classified as having the given disorder. Here’s an example.

Imagine you’re a clinical psychologist whose client says that she’s extraordinarily anxious in social settings and that the anxiety is disrupting her life. If you open your copy of the DSM, you’ll find a relevant diagnostic category: Social Anxiety Disorder. Furthermore, you’ll find specific criteria for determining whether your client’s condition qualifies as a case of this disorder. The DSM criteria for Social Anxiety Disorder include the following (American Psychiatric Association, 2013):

High levels of fear about social situations that involve scrutiny by others, including fear of seeming anxious and being humiliated.

These situations induce such fear consistently.

The person avoids the situations or finds them extremely difficult to endure.

The person has experienced these feelings typically for six months or more, and they cause significant distress or interfere with daily functioning.

The fear is extreme in comparison to the actual danger posed in the situation.

You would then talk to the client; assess the frequency, severity, and duration of her anxiety; and use that information to determine whether she qualifies as having the disorder. The DSM includes guidelines of this sort for each of an enormous variety of disorders, including all the disorders mentioned in this chapter and the next.

When diagnosing clients using the DSM, therapists recognize that any given client could have more than one disorder; psychological disorders often are comorbid. Comorbidity refers to the presence of symptoms of two or more disorders in any one individual (Kessler et al., 1994). Comorbidity can occur for a number of reasons. A biological factor (e.g., a genetic predisposition) could contribute to more than one disorder. One disorder may trigger another; for example, a person may become depressed about her persistent social anxiety. Alternatively, comorbidity can occur simply because disorders overlap; that is, some psychological experiences are, according to the DSM, symptoms of more than one disorder (Cramer et al., 2010).

THE DSM: NOBODY’S PERFECT. The DSM is the most influential book in the field of mental health. Its diagnostic categories provide therapists, researchers, drug companies, insurance companies, and government agencies with a common language for identifying and communicating about mental disorders. Many countries outside the United States use a different diagnostic system, the International Classification of Disorders, or ICD; however, the ICD’s content has been shaped significantly by the categorization system of the DSM (APA Monitor, 2009), thus extending the DSM’s influence. Given the widespread use of the DSM’s diagnostic categories, it is important to examine them critically. Three points stand out:

The DSM’s diagnostic categories change. The DSM has evolved across five editions (the first in 1952 and the fifth, DSM-

5 , in 2013; Blashfield et al., 2014). In this evolution, its content has changed substantially. Newer editions list more disorders than do earlier editions, while also discarding some diagnostic categories that had been used previously.How could the classifications of mental disorders change so much? Did science discover new disorders and find that some old ones no longer exist?

The DSM’s categories are only partly grounded in scientific research. They also rest on professional opinion; health care professionals meet and debate the book’s contents. Professional opinions change, reflecting both scientific findings and shifting social trends (as we saw with homosexuality). The categories thus change from one DSM edition to the next. Ideally, the manual’s categories would be grounded more thoroughly in scientific findings.DSM categories are descriptions, not causes. When diagnosing physical disorders, physicians distinguish between (a) symptoms and (b) their causes. If you tell your doctor that you have chest pain, that is a symptom. When your doctor diagnoses the problem, she does not say that you have “chest pain disorder”; that diagnosis merely would describe the problem you have. Instead, she looks for causes. She seeks a diagnosis (e.g., a digestive system disorder, a muscular injury, a heart attack) that will explain why your symptom occurred. The DSM diagnostic categories, however, are not like this. DSM categories merely describe symptoms; the DSM classifies disorders according to “surface similarity of signs and symptoms, not in terms of their causes” (McNally, 2011, p. 176). Although a physician does not diagnose a person experiencing chest pains as having “chest pain disorder,” the DSM does diagnose a person experiencing prolonged depressed feelings as having “depressive disorder.”

The DSM may cause mental illness to be overdiagnosed. What percentage of people do you think have mental illness? Intuitively, you probably would expect this number to be small; although people have their “quirks,” most people you know don’t literally seem mentally ill. Yet, when DSM criteria are employed, the percentage of people with a disorder is remarkably large. In one survey of thousands of college students, almost half (46%) qualified as having had a mental disorder in the preceding year (Blanco et al., 2008). A similar survey in Europe yielded the startling news headline, “38% of Europeans Are Mentally Ill” (Associated Press, 2011). The percentages are so large that some ask whether the DSM is overdiagnosing mental illness by labeling some everyday, normal human experiences as disorders.

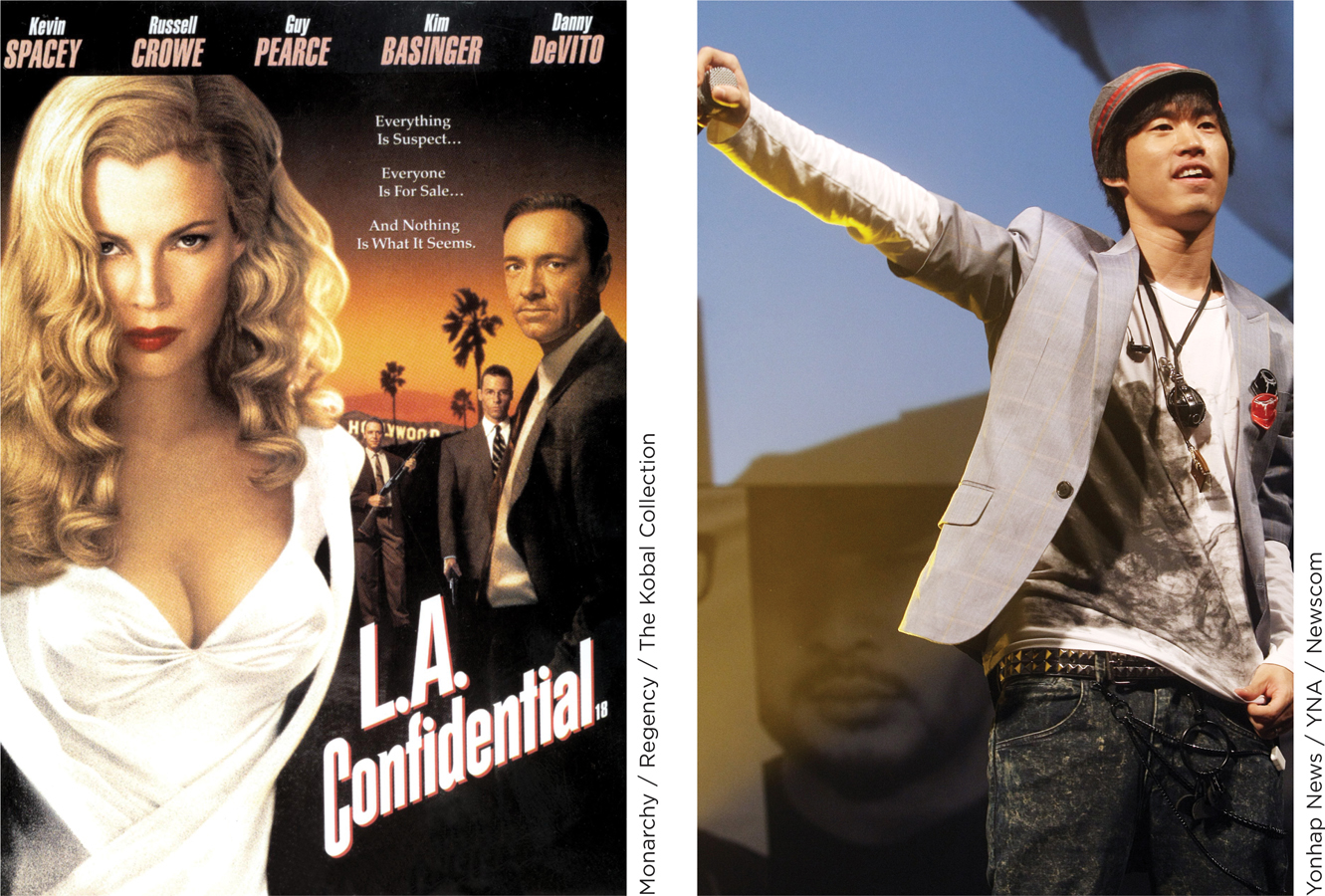

Page 663 Psychological diversity in DSM categories DSM categories classify people according to the symptoms, not the causes, of psychological disorder. As a result, people with different psychological backgrounds can receive the same DSM diagnosis. Based on biographical information, both U.S. film star Kim Basinger (shown here in the 1997 film L.A. Confidential) and South Korean hip-

Psychological diversity in DSM categories DSM categories classify people according to the symptoms, not the causes, of psychological disorder. As a result, people with different psychological backgrounds can receive the same DSM diagnosis. Based on biographical information, both U.S. film star Kim Basinger (shown here in the 1997 film L.A. Confidential) and South Korean hip-hop musician Daniel Lee (also known as Tablo, in the group Epik High) appear to meet DSM criteria for the same disorder: social anxiety disorder. Yet their backgrounds differ. Ms. Basinger has been socially anxious since childhood; she appeared to teachers to be having a nervous breakdown whenever asked to read aloud in class (Cuncic, 2010). Mr. Lee, by contrast, developed social anxiety only later in life, due to a prolonged and public traumatic event. After graduating from Stanford University and returning to his home country, Mr. Lee was wrongly accused of falsifying his academic records. Newspaper articles and Internet sites attacked him for purported dishonesty. He eventually proved that he earned his degrees, but the attacks traumatized him, making him afraid to appear in public. “I’m damaged,” he says. “And I don’t know if I’ll ever be better” (Davis, 2011). A particular concern is that, when diagnosed using the DSM, some people who are experiencing normal sadness are labeled as “mentally disordered” (Horwitz & Wakefield, 2007, p. 6). Throughout human history, people have experienced sadness in response to bad events (e.g., the death of a loved one; the breakup of a relationship). If people’s sadness lasts long enough, they might qualify as having a mental illness, despite experiencing an emotion that is a normal part of human nature (Horwitz & Wakefield, 2007).

Feminist scholars raise another concern. Historically, the professionals who have formulated the DSM and used it to diagnose patients have been men. Some male clinicians may misunderstand women’s experiences. Others may hold gender biases that cause them to treat women negatively. These factors could cause male clinicians to mistakenly judge psychologically normal women as mentally ill (Chesler, 1997). Research shows that clinicians’ views of mental health can be gender-

Finally, cultural and social group differences might cause disorders to be overdiagnosed. Consider cultural differences in reactions to tragedy. In some cultures, such as in urban societies in Cairo, Egypt (Rosenblatt, 1993), grief reactions are extremely prolonged. Just within the United States, grief after the loss of a loved one is, on average, more prolonged among African American college students than European American students (Laurie & Neimeyer, 2008). A mental health professional unaware of these cultural differences might classify as “abnormal” grief reactions that are typical, and perfectly normal, among individuals of the given culture.

Despite its limitations, the DSM is the “gold standard”—the book that holds the greatest authority when professionals classify the different types of mental disorders that require therapy. Now that you’ve learned about this diagnostic tool, let’s look at those therapies.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 3

Though the DSM is the gold standard, it can be criticized on several grounds. For which of the following reasons can the DSM be criticized?

Its categories are too grounded in scientific research and not enough on professional opinion.

A. B. Its categories are descriptions of symptoms of disorders, not underlying causes.

A. B. It was formulated by clinicians whose beliefs about psychological health may be biased against women.

A. B. Its use could lead to the overdiagnosis of mental illness among certain cultural and social groups.

A. B.