15.3 Therapy

Every year, about 24 million Americans receive therapy for psychological disorders. They spend, in total, more than $16 billion for these services (Olfson & Markus, 2010). And those figures are just for outpatient mental health services, that is, therapies delivered to people who do not require an overnight hospital stay. Many others experience severe mental disorders that require hospitalization; for example, more than a third of a million people in the United States are hospitalized for schizophrenia, a disease whose total cost to the U.S. economy runs in the tens of billions of dollars (“Schizophrenia Facts and Statistics,” 1996–

These numbers raise two questions: (1) What are the therapies for which tens of millions of people are spending tens of billions of dollars? (2) Do they work? We’ll address these questions in the rest of the chapter.

Therapy Strategies

Preview Question

Question

Why are there so many different types of therapy?

Why are there so many different types of therapy?

The therapies on which people spend time and money are, in a word, diverse. Two factors fuel diversity. One is the diversity of disorders and people who suffer from them (Nathan & Gorman, 2007). Clinicians develop different therapies for different psychological problems. Furthermore, they adapt standard methods to individual clients; one prominent therapist (Irvin Yalom, interviewed in Howes, 2009) even suggests that “you have to develop a separate new therapy for every single patient. So for some patients the goal will be this and for some the goal will be that.”

665

The second factor is that different clinicians embrace different therapy strategies, that is, different approaches to reducing psychological distress and improving mental health. There are two main types of strategies, psychological therapies and drug therapies:

Psychological therapies (also called psychotherapies) are interactions between a therapist and one or more clients in which therapists speak with, and may create novel behavioral experiences for, the clients. These psychological interactions between therapist and client are designed to improve clients’ well-

being. In psychological therapies, clinicians try to improve clients’ emotional state, increase the quality of their thinking, and enhance their behavioral skills. Biological therapies are interventions that directly alter the biochemistry or anatomy of the nervous system. The most common biological therapies are drug therapies, in which patients receive pharmaceuticals (i.e., chemical substances designed for medical treatment) that alter the biochemistry of the brain. These alterations are designed to improve clients’ emotional state and thinking abilities.

Let’s first explore the psychological therapies.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 4

The main goals of /bb6VrlyetxyJgAXBLqKkcOuz8A= therapies are to improve clients’ emotional state, increase the quality of their thinking, and enhance their behavioral skills. The goal of drug therapies is to alter the biochemistry of the DFWnZgt9nnTSLKGc.

Psychological Therapies

Preview Questions

Question

What are some of the most prominent types of psychotherapy and what is it like to experience each of them?

What are some of the most prominent types of psychotherapy and what is it like to experience each of them?

Which psychological therapy is most popular?

Which psychological therapy is most popular?

Professionals who provide psychological therapies are called psychotherapists. What exactly do psychotherapists do?

It depends. Psychologists hold different beliefs about the best psychological techniques for improving mental health; thus, there are different types of psychological therapy. Five types are particularly prominent: psychoanalysis, behavior therapy, cognitive therapy, humanistic therapy, and the family of group therapies. (The approaches to psychotherapy are very closely related to the various personality theories; see Chapter 13.)

PSYCHOANALYSIS. Psychoanalysis is a psychotherapy strategy developed late in the nineteenth century by Sigmund Freud, a physician in Vienna, Austria (Freud, 1900; Freud & Breuer, 1895). It is an example of insight therapy, in which therapists help clients identify and understand—

The free association method is a therapy technique in which patients are encouraged to say anything that comes to mind when they contemplate their psychological problems; they “free associate” to the problems. Freud instructed his patients not to hold anything back. They were to voice any thought that came to mind, even if it seemed trivial (Bellak, 1961). Freud did not interfere with the free associations. He merely took notes on the client’s thoughts and analyzed their content. The idea was that, eventually, the free associations would lead to deeply significant psychological content, such as memories of traumatic events in the past.

666

Why not just ask clients directly to talk about this significant psychological content? Freud’s answer is that they are unable to do so. Troubling memories are stored in the unconscious, a region of mind whose contents are hidden and unusually inaccessible. In Freud’s theory, the mind is like a library with different levels, and the unconscious is like a large basement level that is locked. The unconscious contains a lot of material, but you can’t access it without a key. The free association method is the key that lets people into the unconscious mind.

Freud explains that some life experiences are so emotionally disturbing that people don’t want to think about them. To stop doing so, people repress them; that is, they transfer memories of the events from their conscious mind (the part of mind of which you are aware) into the unconscious. Once deposited there, the unconscious thoughts do not just go away. Rather, their emotional energy endures. This energy can break out of the unconscious and cause emotional and physical distress. People experience distress but don’t know why; they lack insight into its unconscious causes.

Through the free association method, people gain this insight. As therapy proceeds, they uncover topics of deeper and deeper emotional significance, eventually encountering the underlying cause of their emotional disturbance. This process can be slow. Patients may be in psychoanalysis for years, overcoming their resistance to thinking about emotionally disturbing past events only gradually (Sandell et al., 2000). But once they gain insight into this material, aided by interpretations provided by the therapist, their mental health is expected to improve. Their conscious mind should gain strength, the unconscious should lose strength, and the person should become relatively free of debilitating psychological distress (Cameron & Rychlak, 1985). A large-

Freud’s approach exemplifies the medical model of psychological disorders (Elkins, 2009; Macklin, 1973). The patients’ problems of living—

THINK ABOUT IT

Freud kept notes on his patients’ progress and, based on those records, concluded that psychoanalytic therapy works. Is that good scientific evidence? How could you test the effectiveness of psychoanalytic therapy scientifically?

Another key psychoanalytic process is transference, which occurs when a patient unintentionally responds to a therapist as if the therapist were a significant figure (e.g., a parent) from the patient’s past. Emotions originally experienced with the significant figure are “transferred” to the therapist. Transference is significant in that, once past emotions are reexperienced in therapy, they can be analyzed. Through this analysis, the patient can gain insight into how past emotional experiences are causing current distress (Cameron & Rychlak, 1985).

Have you ever met someone who reminded you of a significant person in your life? Did you treat this person in ways that were similar to the way you treat the significant person? This experience is similar to transference.

During and after Freud’s lifetime, a large number of other therapists developed therapy methods that were inspired by, but were not identical to, Freud’s approach. The resulting set of therapy approaches—

667

BEHAVIOR THERAPY. Behavior therapy is a strategy in which therapists aim to directly alter clients’ patterns of behavior. By learning more adaptive ways of behaving, clients’ psychological lives improve (O’Donohue & Krasner, 1995).

Behavior therapy differs considerably from psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysts analyze the client’s past. Behavior therapists focus, instead, on the present and the future. They try to identify behavioral problems the client is experiencing now, and to teach new behaviors that will be effective in meeting upcoming challenges. This practical, problem-

Behavior therapists change clients’ behavior by altering their environment. They know that, in general, environmental experiences shape behavior (Skinner, 1953). Strategically changing clients’ environments therefore may change their behavior and improve their well-

Behavior therapy is grounded in research on learning (Chapter 7). Historically, learning researchers first identified environmental factors that modify emotion and behavior in laboratory studies. Behavior therapists then put the research findings into practice, via three steps of reasoning: (1) Clients experience distress because environments they experienced in the past did not teach them behaviors that are useful in their present circumstances; (2) it’s never too late to learn, thus clients can learn useful new behaviors in therapy; and (3) factors shown, in basic research on learning, to modify emotion and behavior could be used to teach clients the new behaviors (Bandura, 1969; Schachtman & Reilly, 2011).

To see how the behavior therapy strategy can be put into practice, consider an application in which therapists worked with couples experiencing high levels of marital distress (Christensen et al., 2004). For the couples, being in therapy was like taking a class—

Behavioral exchange: The couples were taught to generate lists of positive things that they could do for their partners.

Communication training: Therapists taught couples new ways of speaking, with a key behavior being first-

person statements (e.g., “I feel bad when you make a mess around the house”) instead of second- person statements that make people defensive (e.g., “You are a slob.”) Listening skills: Couples learned how to summarize and paraphrase statements their partner made during conversations. Paraphrasing makes people know they are being understood, which benefits conversations and, more generally, relationships.

668

To determine whether therapy worked, therapists measured marital satisfaction both before and after therapy. Behavior therapy significantly improved couples’ satisfaction with their marriages (Christensen et al., 2004).

An effective behavior therapy technique is the token economy, in which therapists reward desirable behavior by administering reinforcers that make those behaviors more likely to occur (see Chapter 7). The reinforcers are tokens—

Token economies illustrate a fundamental principle of behavior therapy, namely, that behavior is controlled by its consequences. People do things that bring rewards. They avoid performing behaviors that bring punishments. Following this simple yet powerful principle enables behavior therapists to reduce people’s maladaptive behavior.

CONNECTING TO LEARNING AND TO BIOLOGICAL MECHANISMS

Did any of your grade school teachers create a token economy in the classroom?

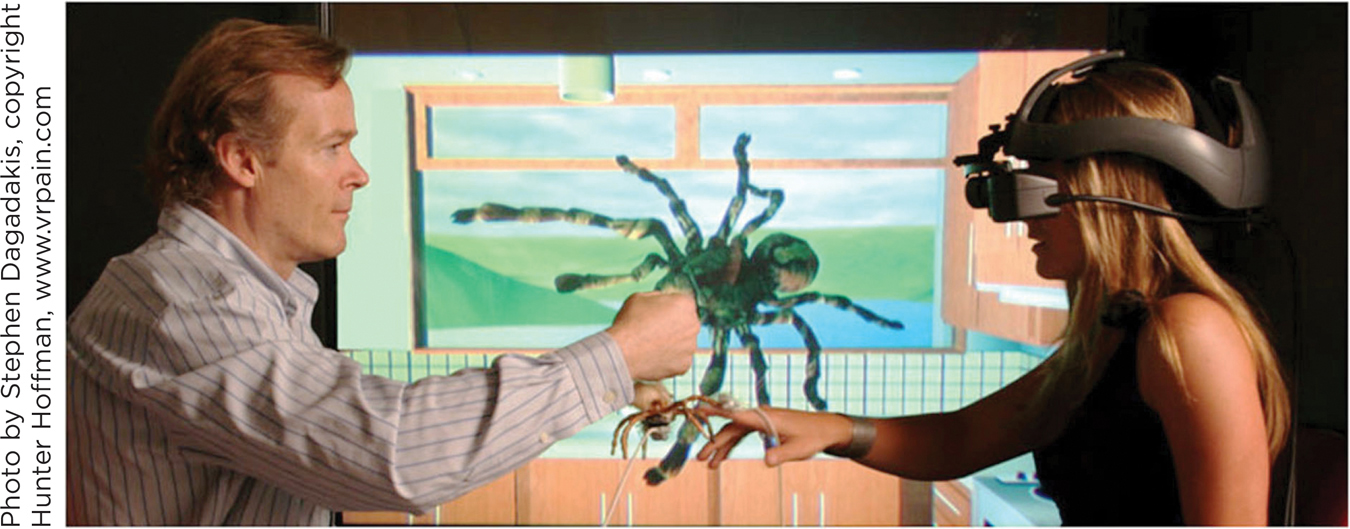

In addition to modifying behavior, some behavior therapy techniques directly target emotional reactions. Behavior therapists combat the emotions of fear and anxiety with exposure therapy, in which clients are brought into direct contact with an object or situation that arouses their fear (McNally, 2007). A client who is obsessively anxious about germs, for example, may be exposed to materials that are dirty. Someone afraid of heights may be brought to a high floor of a tall building. Therapists ensure that no harm occurs to the client during exposure. The client, then, simultaneously experiences (1) the feared object and (2) an absence of harm. This two-

The behavior therapist Joseph Wolpe (1958) pioneered an exposure therapy called systematic desensitization. Systematic desensitization reduces fear by exposing clients to feared objects in a slow, gradual manner. The exposure can occur through real-

669

CONNECTING TO COGNITIVE PROCESSES AND TO NEURAL SYSTEMS

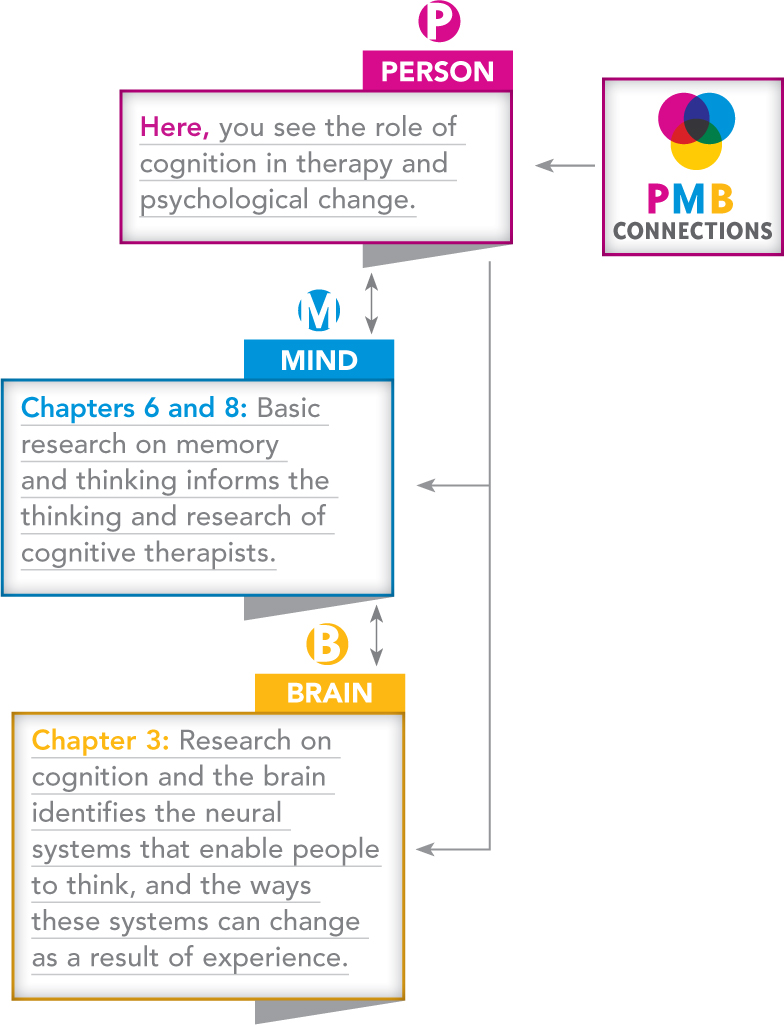

COGNITIVE THERAPY. In cognitive therapy, therapists try to improve mental health by changing the way in which clients think. They try, in other words, to change clients’ cognitions.

Cognitive therapy is grounded in a simple yet important idea: Thinking processes are at the heart of psychological distress. Certain types of thoughts—

These negative thoughts are self-

Cognitive therapists argue that many of these negative beliefs are irrational. Irrational beliefs are demanding, dogmatic thoughts that cause people to experience negative emotions (Ellis & Dryden, 1997). The beliefs are called “irrational” because they distort reality illogically. In so doing, they bring about psychological distress; people irrationally make themselves feel bad through their own beliefs.

The irrational thoughts targeted in cognitive therapy may be familiar to you. Do you ever think that you can’t be happy unless you have more friends? Or more money? Or that you must become more successful in school or must make someone else happy for you to be happy yourself? Such beliefs are common yet, to the cognitive therapist, irrational because they can doom you to unhappiness. The cognitive therapist thus combats them. For instance, when a client said he was unhappy because his wife’s pushy parents did not respect him, his cognitive therapist explained that his unhappiness was caused not by the in-

670

One proven method for changing negative, irrational cognitions is Beck’s cognitive therapy, developed by the physician Aaron T. Beck (1979). Beck explains that the thoughts which create distress often are automatic thoughts, that is, thoughts that spring to mind rapidly and unintentionally. People don’t intend to think thoughts that create distress. They just pop into mind. When contemplating the future, the depressed person automatically thinks, “Things will go badly.” When considering an upcoming social event, the socially anxious person automatically thinks, “I’m going to look like an idiot.”

Cognitive therapists try to change automatic thoughts through conversations with clients that aim to achieve a number of therapeutic goals:

Increasing awareness: Clients may be unaware of how negative their thoughts are. The cognitive therapist’s first goal, then, is to increase awareness, that is, to help clients see how their own negative thinking contributes to their emotional distress.

Challenging negative thoughts: Therapists then challenge the negative thoughts they have identified. They question the logic and evidence behind the thoughts.

Suggesting positive thoughts: Therapists not only attack negative thoughts. They also encourage clients to replace them with more positive, adaptive ways of thinking.

Let’s see how cognitive therapy works in a case involving a suicidal patient (P). The therapist (T) tries to prevent a suicide attempt by changing the patient’s thoughts—

T: Are there any other reasons for dying?

P: I just feel I’m wasting everyone’s time. No one can help me. I’ve been like this since I was a child.

T: Some reasons for dying are that you would escape from your despair, the children would not have to put up with you, that John would realize how bad you’ve been feeling, that you wouldn’t be wasting people’s time any more. Is there anything else?

P: [Pause] No, I don’t think so.

T: Can you think of any disadvantages that there may be to trying to kill yourself?

P: Disadvantages?

T: Yes.

P: [Long pause] I think I might fail—

end up with brain damage or worse and be more of a burden. T: Any other disadvantage?

P: Sometimes, when things are going a bit better, I realize how upset the children would be. Michael and Marion climbed into bed last Saturday morning and gave me a big kiss. They’d tried making some toast. The marmalade got everywhere. [Smiles, then tearful.]

T: Anything else?

P: Well, I don’t know what’s on the other side—

of death, I mean. I don’t have any religious beliefs, but I sort of think, well, it scares me. It might not be peaceful. T: So sometimes you see there may be disadvantages to dying, or to attempting to die: that you could end up worse off—

physically damaged in some way; that the children would miss you; that the other side might not be peaceful.

As you can see, the cognitive therapist tried to change the client’s way of thinking. The therapist did so subtly—

In some ways, cognitive therapy resembles behavior therapy. Both endeavor to teach clients new skills. Both focus on challenges in the here-

671

HUMANISTIC THERAPY. Humanistic therapy is a strategy in which therapists provide clients with supportive interpersonal relationships. In humanistic therapy, the quality of the relationship between the therapist and the client is key. Therapist and theorist Carl Rogers explains the approach: “If I can provide a certain type of relationship, the other person will discover within himself the capacity to use that relationship for growth and change, and personal development will occur” (Rogers, 1961, p. 33).

Humanistic therapists believe that a good client–

Of course, for many people the answer to the question above is no; they lack a strong, supportive relationship with someone who listens closely to them. This absence can harm psychological development. Humanistic therapists tell us that just as a seed needs water to grow, a person needs personal relationships to grow. By providing such relationships in therapy to people who may lack them outside of therapy, the humanistic psychologist provides the support that clients need to achieve psychological growth.

To develop strong personal relationships with their clients, humanistic therapists follow three basic guidelines—

Genuineness: In therapy, humanistic therapists express their true, genuine feelings to their clients. They do not maintain a cold, detached, “scientific” personal style of the sort you might find when talking to a physician. Rather, the humanistic therapist is an open and honest person who is willing to express his or her genuine feelings as they arise during the therapy encounter.

Acceptance: Humanistic therapists are accepting of their clients. They never reject a client’s thoughts and actions as being foolish or inappropriate. The client is always respected as a person of dignity and worth. This acceptance establishes a psychologically safe setting in which clients can freely explore their personal experiences. The humanistic therapist’s term for this acceptance is unconditional positive regard, which is the expression of positive feelings toward the client no matter what the client does and says; the positive feelings, in other words, are expressed unconditionally.

Empathic understanding: Humanistic therapists strive to display empathic understanding, which is an understanding of the clients’ psychological life from the perspective of the client. The humanistic therapist does not try to diagnose an inner mental illness that is unknown to the client. Instead, the therapist strives to understand what clients know about, and feel about, themselves. Furthermore, they ensure that clients know they are being understood. They do this through active listening, that is, listening in which one conveys to speakers that they are being understood from their own point of view (Rogers & Farson, 1987).

A key active-

listening technique is reflection, in which therapists recurringly summarize statements made by the client; they “reflect” the content of clients’ statements back to them. For example, a client might say, “I’ve been feeling really bad that I haven’t done better at college; my parents had been hoping I’d do well; they never got a chance to go to college themselves and they’re counting on me, and I’m blowing it.” The therapist could reply, “You’ve got a deep sense of guilt about not meeting your parent’s expectations.” By encapsulating the meaning and emotional tone of the statement, the therapist shows the client that she is being understood empathically. 672

Do you ever “reflect” statements made by your friends in everyday conversation?

Humanistic therapists believe that these three therapeutic conditions are not only necessary for therapy to succeed, but also are sufficient. Humanistic therapists do not try to modify their clients’ thoughts, as cognitive therapists do. They instead try to develop a relationship in which they can understand their clients’ thoughts. Once this relationship is achieved, the client naturally “will discover within himself the capacity” to grow (Rogers, 1961, p. 35). The agent of psychological change, in the humanistic view, is not the therapist. It is the client.

GROUP THERAPY. Therapy does not always consist of one-

One benefit of group therapy is efficiency. Mental health services can be delivered to more people, in any given amount of time, when therapy is conducted in groups. Efficiency, however, is not group therapy’s main advantage. As Yalom (1970) explained in a classic text, group therapy introduces a number of psychological processes that may benefit clients, including the following:

“Misery loves company”: In group therapy, clients see that they are not alone. They encounter others who share similar psychological difficulties. This makes clients aware that their life circumstances are not as unusual or “strange” as they may have thought.

Group therapy Many psychologists conduct therapy in groups. Interpersonal interactions within the therapy group can provide insight into interpersonal problems that occur in clients’ lives outside of therapy.

Group therapy Many psychologists conduct therapy in groups. Interpersonal interactions within the therapy group can provide insight into interpersonal problems that occur in clients’ lives outside of therapy.673

Helping others: Clients in group therapy may help others by providing advice or emotional support. The experience of helping others can prove beneficial to the person providing the help.

Building social skills: In group therapy, people often receive feedback from others on their behavior. As a result, they may learn about personal behaviors that leave a bad impression on others, such as failing to establish eye contact or talking obsessively about oneself. By correcting these tendencies, people can increase their social skills and thus develop more positive relationships.

Therapy group as a microcosm of everyday life: After a number of group therapy sessions, people’s behavior in the group may resemble their behavior in everyday life. In particular, individuals may exhibit, in the group, the same negative behavior that interferes with their everyday relationships. Someone who is domineering toward relatives may become domineering toward group members. People concerned about social rejection in everyday life may become concerned about rejection from group members. When this happens, the therapist and group members can provide feedback that enables people to become aware of negative aspects of their behavior. This awareness is a first step in bringing about change.

Group therapists foster these beneficial group dynamics through a number of steps (Yalom, 1970). First, they form and maintain the group, ensuring that members show up and participate in discussions. Second, they establish and maintain norms for group behavior—

Table 15.2 summarizes the five different therapy strategies we have discussed.

| Therapy Strategies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Therapy |

Main Therapeutic Goal |

Key Therapy Processes/Techniques |

Key Figure |

|

Psychoanalysis |

Gain insight into unconscious causes of psychological distress |

|

Sigmund Freud |

|

Behavior therapy |

Use environmental experiences to teach new behavioral and emotional responses |

|

Joseph Wolpe |

|

Cognitive therapy |

Identify and modify clients’ irrational, self- |

|

Aaron Beck |

|

Humanistic therapy |

Provide an interpersonal relationship that enables psychological growth |

|

Carl Rogers |

|

Group therapy |

Use group dynamics to instill hope and increase self- |

|

Irvin Yalom |

15.2

674

TRY THIS!

Could you tell the difference between the different approaches to psychotherapy if you saw them put into practice? Find out with this chapter’s Try This! activity. Go to www.pmbpsychology.com, where you will see videos of therapists who illustrate different forms of therapy. ![]()

ECLECTIC, INTEGRATIVE PSYCHOLOGICAL THERAPIES. After learning about these different forms of therapy, you might be wondering which is most popular. It turns out, rather than “picking one,” a popular strategy is to combine the virtues of different approaches to fit the needs of the individual client. Integrative psychotherapy is an effort to combine systematically the methods of different schools of therapy (Thoma & Cecero, 2009). The resulting combination is described as eclectic therapy, an approach that creatively draws upon any therapeutic method available (Jensen, Bergin, & Greaves, 1990). (The notions of “integrative” and “eclectic” therapy overlap; some therapists describe their approach as “eclectic-

In surveys, more than two-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 5

nZaQUxqDXEIp/Wm541k+wLqkGbHQhmuupkFye+iunXJmetl7PfFxVxEJlz+ihiAbWNbO5xJTeUrsWAIEvpL6iQUwi2VZbSuqe/9dpwIqcURVQH0yuInQT6SqSCuUWfNs58+A0hrOPTzgiyzSTCF7WcXTwVvetpJuna2RINne7Y/4RdBFNBms622Y9ph3wQWa6nlPqoNV6jDe5D/Y+EfKfmr5VMOAw7sQWzy1M3r0V7fOj8DwNYPq8ZueIuF0+ep4dXsjYKy9/PHP/DcSlZK4zDW53bhUdrBmFKImhSLCnszPaOgQ/Yow5KwnH48bW3n4BF5rSomONRsCJAs6ZfTO4nTOkVgMnJM8bduqunjaG5kMsTH2qB2LuEkyVUJLX7VTY0cO/QHJKFRUDUe8P/6khLZ0+73AYI1YXY/zIIL+RJa80P+sYcPgZ8hOG3xs6FTNYS57FohtWq3S/yFkA3y5jd3RcIevB5HbfWcxQZQMrzz1tqN1Uy+v/sp0NRRC838NDlLkn7fxZOG65VWi5bezIZpbzB5X0ryDBCy0R9v27Xsz0ps1RCL3zlbH9b8GbJxDgrIHr8hQ5hkwLC0ItuMzKi4NwgtkQctLEs7HstT8IuKf9TOKjEa30f2oJPhWnWigPJOBJ+XO0e+wSRpu/t9eARLBNo3KfIt2o52RhAN229KScOea2iNCZpXG9WjV/WLflCjNtc2t5QLx7UNzLjA/sx8zMwaAFRjgZY+O7moDP6az9KcAZcEJH7J2ZkkHA3JhKNluTO9HwoUYFPJspAbY6owaWx8175AWHvPvBhcFvniC2K+UIYDJegKyzEfY2D4wAkod0xNw1r0mnS2mehJlDl+w2gAJDlBMpFV80+wQKTdRAiM3fzyvoBxN2TVXbLNwtEUVgNgghuvOM8hib4NBCwe+9EDrz+4wA4XVxD7LY2IknTd6YeNkZMXEnz9PZNyJV8mPDy0c64cvqXSbYAI8DrHLjanvm5w0Q1gtJVxUxglAm6CGmdLHzK15g8S38La9yazWBH/syAxY/Pxl/ZRrV0hvY9C6CSEUkETk8flOfRf9MBzKlioLeaeOZh6SYABbZWXaGTNMSw4xJJzZXja/rjRSwb12IR+E2bq/a7Vz5SJJVHGoc3cSWqQ1MUSkEGKECxPTcNUranUIR3RD4ApY3la+j8pJZNj5gG5NPxtAclyfEIRGE9bkrvZbgKpQvbejBQY45BVy0FJKhVc39iodqsZppb/5jx4M/Tvdpti8K0P3AwwVKgyogphye5nF9i29kJwhNlK7RuQxIBYexPS0nM68ofNkERMpDS1p0UjL+ZYEOyHwOYl5d7+jlgycuOiYTtw3SI500LR742C78JhJsdQy+BM328XEqsU1XmQqjPSaxGspiT5j5xf9X1wVc0XeASa2B14CBJGcce3sk6FcKRle0AL3ks3P9+87VHO8wxGRXs2e/6Q+6Dou2Rpu9b93yJhbOrwB18fZHuEde6DNXw4tOseJkKPtdKdaZQ==Drugs and Other Biological Therapies

Preview Questions

Question

How did physicians figure out that psychological disorders could be treated with drugs?

How did physicians figure out that psychological disorders could be treated with drugs?

How do drugs affect mental health?

How do drugs affect mental health?

What are some alternatives to drug therapies?

What are some alternatives to drug therapies?

Psychological disorders are just that: psychological. Their defining features are troubling alterations in psychological experience: thought, emotion, and behavior. Yet if you want to treat these disorders, one option is to shift from a psychological to a biological level of analysis.

675

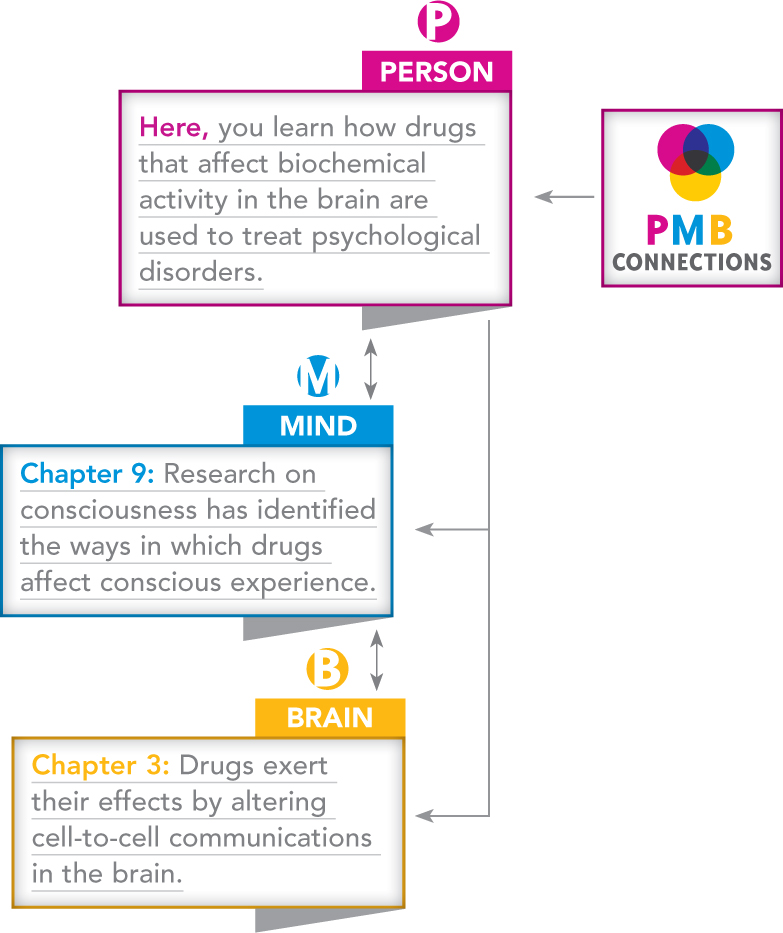

Psychological disorder can result from a malfunctioning brain. If so, then altering brain function might relieve psychological distress. Biological therapies for psychological disorders, as noted earlier, are therapy approaches that alter the anatomy or physiology of the brain in an effort to improve mental health. By far the most popular of the biological therapies are drug therapies.

THE HISTORY OF DRUG THERAPIES. The discovery that drugs could alleviate mental illness was accidental. In the 1940s, a physician in France was searching for a drug that would help surgical patients during their postoperative recovery. The drug he tried, thorazine, worked; postoperative patients were calm and relaxed. Psychiatrists guessed that this drug might benefit others—

Their guess proved correct. The drug originally designed for surgical patients calmed people suffering a state of severe excitation known as mania (discussed later in the chapter). It had additional beneficial effects as well. After taking the drug, patients whose thinking was confused and who were worried that others were out to get them began to think more clearly.

These unexpected findings triggered a burst of scientific research in the 1950s that ushered in a new era in the treatment of severe mental illness (Valenstein, 1998). The medical community quickly embraced the finding that psychotic disorders (Chapter 16) could be treated with drugs.

Other accidental findings followed. Physicians noticed that when patients received a drug designed to treat tuberculosis, their mood changed; the drug made them happy. This drug quickly was put to use in the treatment of depression (Valenstein, 1998).

Not all drug therapies were developed accidentally, however. A treatment for depression was based on a theory about brain functioning (Carlsson, 1999). The theory was that the neurotransmitter serotonin is related to mood; specifically, greater serotonin activity in the brain should make mood more positive. Scientists designed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs, to alleviate depression by increasing serotonin activity. They do so by interfering with a biochemical process known as reabsorption. In reabsorption, some of the serotonin that one neuron could use to communicate with a second neuron is absorbed back into the first neuron. SSRIs block reabsorption (Figure 15.1). The amount of serotonin available for neuron-

Drug therapies have revolutionized the treatment of mental illness. The biggest change occurred in the treatment of psychotic disorders. Until the mid-

WHY DRUGS HAVE PSYCHOLOGICAL EFFECTS. You learned in Chapter 2 (also see Chapter 3) that brain cells communicate chemically. Chemical substances known as neurotransmitters travel from one brain cell, or neuron, to another. These chemical transmissions determine the level of activity of the cells of the brain.

These basic facts about brain functioning are key to understanding why drugs affect mental health. Drugs are chemical substances. Most chemical substances you ingest have little or no effect on brain functioning because of the body’s built-

676

677

One way in which drugs have psychological effects, then, is that they directly alter chemical activity in the brain. A second way that drugs can affect mental health is through placebo effects. A placebo effect, in drug therapies, is any medical benefit that is not caused by biologically active properties of the drug. Researchers demonstrate placebo effects by giving some patients pills that have no medicinal qualities—

What is the cause of placebo effects? The main source appears to be people’s beliefs. People who get a medication (or, in the case of a placebo, a pill that they think is a medication) believe that, as a result, they will improve. This expectation of improvement becomes a “self-

How would you feel if you learned that an improvement in your own health was due to a placebo effect?

CONNECTING TO CONSCIOUSNESS AND TO CELLULAR COMMUNICATIONS

Placebo effects raise challenges for researchers who want to show that a real drug uniquely benefits mental health. They must demonstrate not only that people who receive the drug improve; they also need to show that people on the drug improve more than those who get a fake drug—

OTHER BIOLOGICAL THERAPIES. The psychological effects of drug therapies can be slow. Even the manufacturers of antidepressant drugs recognize that patients may not experience benefits until after taking them consistently for four weeks or more (“Highlights of Prescribing Information,” 2014). If a patient is severely depressed and suicidal, or if a range of medications has not helped, some therapists then employ electroconvulsive therapy.

In electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), physicians deliver electrical currents to the brain. The electricity creates a brief brain seizure, that is, a period of abnormal electrical activity in the brain, during which a person loses consciousness. Studies indicate that electroconvulsive therapy benefits severely depressed individuals, reducing depressive symptoms in the majority of such patients (Rudorfer, Henry, & Sackeim, 2003). Why does it work? Good question; the mechanisms through which ECT reduces severe depression are not well understood. However, recent evidence indicates that the therapy may disrupt connections in the brain that contribute to depression. Specifically, the brains of people with severe depression often feature atypically strong connections among those parts of the brain involved in thinking and in emotion. ECT can disrupt these connections, which reduces depressive symptoms (Perrin et al., 2012).

678

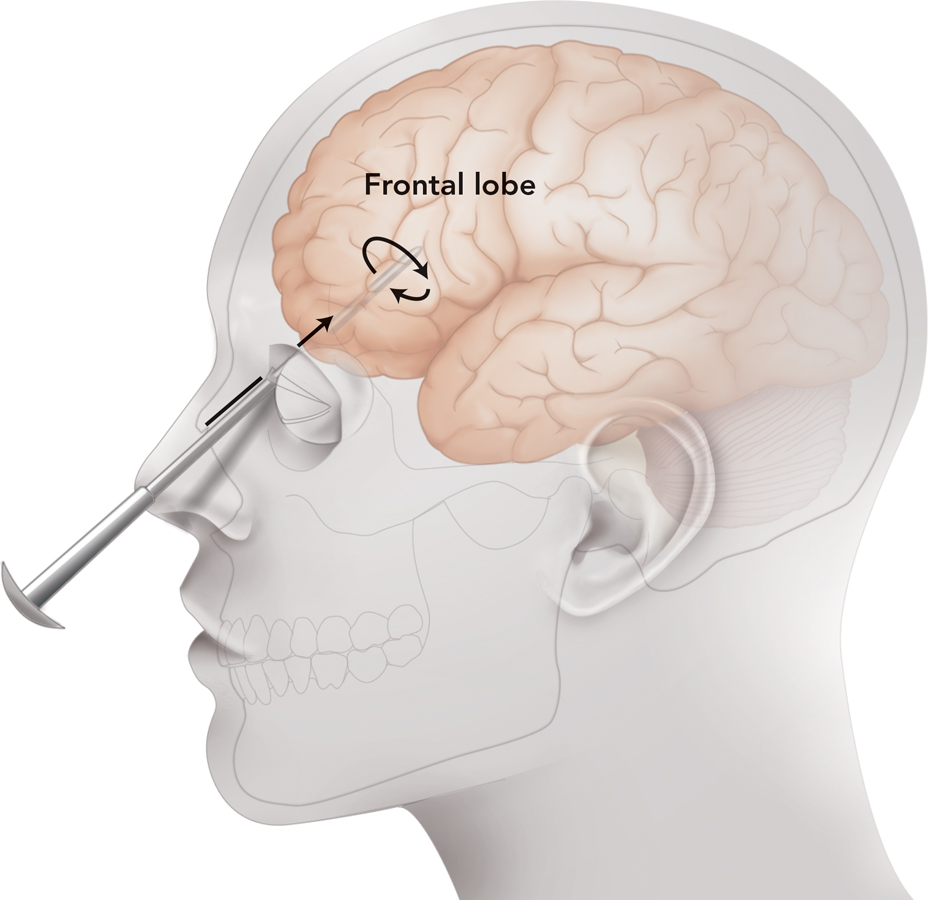

Another alternative to drug therapies that has been tried is surgery. In principle, surgeons could treat mental disorders by intervening directly in the brain. They could remove a malfunctioning brain system or sever its connections to other regions of the brain, thereby cutting off its influence. In lobotomy, a surgeon damages brain tissue in the frontal regions of the brain, specifically, the brain’s frontal cortex.

The origins and popularity of lobotomy lie in the past. Physicians in the first half of the twentieth century believed that a malfunctioning frontal cortex was the root of severe mental illness. They thus reasoned that damaging the cortex and its connections to the rest of the brain would alleviate mental illness (Lerner, 2005). This idea affected medical practice; by mid-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 6

For each of the “answers” below, provide the question. The first one is done for you.

Answer: Though many drug therapies were developed accidentally, the use of this class of drugs was based on the theory that the neurotransmitter serotonin was related to mood.

Question: What are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)?

- kVhon7mKJLFJ2QLooai4b5BvKyva5u84ttMdPoLHMHoHOzZZicn5Zd9AtUlgVw48blVgrYRtwgXZ0skWVXOpupb+sXtd3AdW4ix82OnYxQANr/RNwX5oYTHEusCzu3MaVO1UEVfKNTP3Fav152EPzIn/n4IKNXywz733tUdXLs6nYV7DahAv6VDe2X3ODsr8E4BcTtngz/NHM7kutdYhNQ==

- gcKVR2lv/JVHLVs1Cq32a4iJjJUge4vRuV4GWXtLUuUlcAJwjF2FQAjFclzkUmkPcYIYYKmrCld/Fwwl3eMm89EGmL+7312k3PV4MJxlT3DlBFGrAz4CzPO/uipDMhJLfCkJNGE+yeI5LHnkagbuEzVfnaV3vbwQaTTsPMD2phVeMiSLhICQb3HR9hqR5yogLG1EA5248V5cMQxa++uqY6hyM+A=

- aPov//mvY7Te1Jxo8h1r5gg43N3+I0GmUixFIavmKmzzPQI6UVMUozVtK32GYmgczbZJKnSjujkzwELFy0LkGcXdZM/aRzjQFxEXqkLrJmGb2TMa/hm18WeUROfAdgw0

- kPBIA9T+qHsuYlTrubj7bkwmpkE2qSkeOpT0ci97GeEo33Mzv5DAh14tVn5LxGM1zXjoNm+KivXT/gRRje5kz7EG2EIu5U7x2/jw3h5nqGLxZtW7tY2er8IqGog=

b. What are psychoactive substances? c. What is the placebo effect? d. What is electroconvulsive therapy? e. What is a lobotomy?

679

Evaluating the Interventions: Empirically Supported Therapies

Preview Question

Question

What’s wrong with using case studies as evidence for a therapy’s effectiveness?

What’s wrong with using case studies as evidence for a therapy’s effectiveness?

People who suffer from psychological problems have one big question: Which therapies work best? They want therapies that will improve their mental health, and quickly.

In the early days of clinical psychology, it was hard to tell which therapies worked best. Actually, it was hard to tell if they worked at all. Evidence of therapy effectiveness was meager and of poor quality. The predominant evidence was case studies; therapists reported on the effectiveness of their favored therapy method with individual patients. Case study evidence has two big limitations (see Chapter 2):

Potential bias: Because therapists prefer their own therapy method, they may be biased when interpreting and reporting on its effectiveness (Kendall, 1998).

Lack of a control group: When an individual patient improves during therapy, there is no way of knowing whether that person would have improved in a similar manner even without therapy; some mental health problems dissipate naturally over time.

To identify cause and effect—

Today, this superior evidence is readily available. Clinical psychologists conduct research to identify empirically supported therapies (Kendall, 1998), that is, therapies whose effectiveness is established in carefully controlled experimental research. To qualify as an empirically supported therapy, a therapy method must be shown to be superior to no-

Many types of therapy have, in fact, received empirical support—

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 7

A theory is 6qkXZmGr2AqjHFH/OseV4g== supported when it has been demonstrated to be more effective than a no-

RESEARCH TOOLKIT

The Double-Blind Clinical Outcome Study

Scientists are people, too. When conducting a study, they usually hope it will work. They hope, for example, that a therapy they have devised will prove superior to a no-

These hopes raise the possibility of bias. Scientists may make observations, and interpret results, in a way that is favorable to their own theory.

680

Such bias can occur in any science. But in psychology, the possibility for bias is doubled because the object of study—

How can researchers overcome these biases and obtain results that are not “colored” by their hopes and those of their participants? The best strategy is the double-

A double-

You might be wondering, “Well, if nobody knows who’s in which condition, how can they tell if the experiment worked?” The answer is that in a double-