15.4 Depressive Disorders

Everybody feels depressed sometimes. A bad exam grade, a bad haircut, rejection by a college, or rejection by somebody you asked out on a date can ruin your mood for hours or days. Yet these temporary changes in mood are not what psychologists mean by “depression.” To a psychologist, the term refers to a condition that is more severe. Depression is a psychological disorder that includes feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and fatigue; a loss of interest in activities; and changes in typical patterns of eating and sleep. In depression, these symptoms last for weeks (National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 2011).

The term “depression” does not refer to a single disorder. Rather, there is a family of depressive disorders, that is, distinct psychological conditions that each include depressive symptoms. Let’s explore two prominent depressive disorders: Major Depressive Disorder and Bipolar Disorder (previously called Manic-

Major Depressive Disorder

Preview Questions

Question

What defines major depressive disorder and how prevalent is it?

What defines major depressive disorder and how prevalent is it?

What therapies effectively treat major depressive disorder?

What therapies effectively treat major depressive disorder?

“It hit me what a complete mess I had made of my life. That hit me quite hard. We were as skint [poor] as you can be without being homeless and at that point I was definitely clinically depressed. That was characterized by a numbness, a coldness and an inability to believe you will feel happy again. All the color drained out of life” (ABC News, 2009).

The woman quoted above was suffering from major depression. But it didn’t ruin her life. She managed to cope quite successfully, in part—

DEFINING FEATURES AND PREVALENCE. Major depressive disorder is defined by a set of symptoms; a person is diagnosed with major depressive disorder only if these symptoms last two weeks or longer. They include the following:

Consistent depressed mood

Loss of interest in most daily activities

Change in body weight

Change in sleep patterns

Fatigue

Feelings of worthlessness, hopelessness, or helplessness

Difficulty concentrating

Thoughts of suicide

No one symptom is necessary in order to be diagnosed with the disorder. Individuals with major depression are people who exhibit a majority of the symptoms for at least a two-

Major depression is a relatively prevalent disorder. A survey of U.S. adults indicated that 6.7% of the population suffered from major depressive disorder at some point during the previous year (Kessler et al., 2005). That’s about 15 million people experiencing a disorder that brings despair and lethargy that can utterly disrupt one’s life. Furthermore, the lifetime prevalence of the disorder—

Every day, though, sometimes more than once a day, sometimes all day, a coppery taste in my mouth, which I termed intense insipidity, heralded a session of helpless, bottomless misery in which I would lie curled in a foetal position on the sofa with tears leaking from my eyes, my brain boiling with the confusion of stuff not worth calling thought or imagery: it was more like shredded mental kelp marinated in pure pain. During and after such attacks, I would be prostrate with inertia, as if all my energy had gone into a black hole.

—Les Murray, Killing the Black Dog

Different groups have varying chances of becoming depressed. Major depression is more frequent among people living in poverty than among those above the poverty line (Riolo et al., 2005). Ethnic groups also differ. In one large-

TREATMENT. A number of the treatment strategies discussed earlier in this chapter have been used successfully to treat major depression. Let’s now look at four options: behavior therapy, cognitive therapy, interpersonal therapy (which draws from psychodynamic and humanistic therapies), and drug therapy.

Behavioral therapists emphasize that the environment affects people’s psychological life. Some environmental events make almost anyone feel bad, whereas others make virtually everyone feel good. People become depressed, according to the behavioral approach, when they do not experience enough pleasant activities (Lewinsohn & Graf, 1973). If you sit around by yourself doing nothing at all, day after day—

What, then, should you do to alleviate depression? The behavioral strategy involves two steps. First, therapists instruct clients to keep track of both their daily activities and their mood during these activities; this enables clients to see how environmental events trigger good and bad moods. Second, therapists devise strategies that enable clients to avoid events that trigger depression and to engage in more activities that improve mood. One team of behavior therapists applied this approach when working with a depressed single mother. They found that the woman had eliminated virtually all positive social events from her life in order to cope with the demands of parenting. Therapists showed her how to increase her social contacts while also handling depressing household chores more efficiently so that she would have time for a social life. After a few weeks, her mood substantially improved (Lewinsohn, Sullivan, & Grosscup, 1980).

In what environments do you experience good moods?

A second approach is cognitive therapy. Aaron Beck (1987) identified a “cognitive triad”—three interconnected types of thoughts—

Good news for people suffering from depression is that cognitive therapy works. Meta-

Another effective approach is interpersonal therapy. In interpersonal therapy, therapists try to identify, and change, interpersonal problems that contribute to a client’s current depression. A key aim is to reduce the client’s social isolation by expanding his or her network of relationships (Klerman et al., 1984). Interpersonal therapy is inspired by two of the broad therapy strategies you learned about earlier: the psychodynamic approach, which, in developments made after Freud’s lifetime, began to emphasize the importance of analyzing client’s interpersonal relationships (Sullivan, 1953); and the humanistic approach, whose central tenet is that strong interpersonal relationships are the foundation of healthy psychological growth. In practice, interpersonal therapy is similar to cognitive therapy for depression, with both approaches targeting irrational thoughts about interpersonal relationships (Ablon & Jones, 2002).

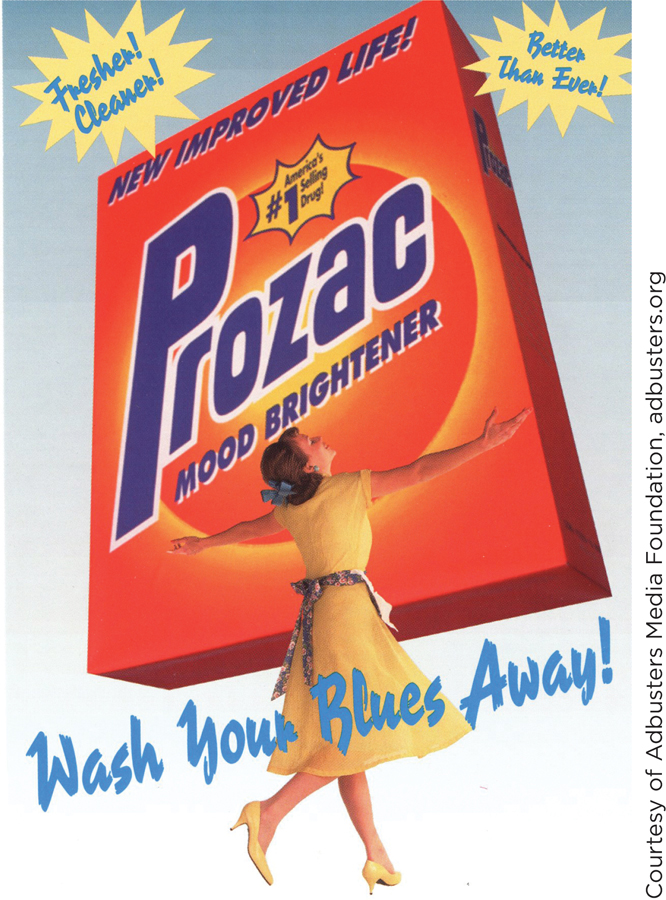

A fourth strategy to combat depression is drug therapy. Antidepressants are among the most widely prescribed of all prescription drugs in the United States. Nearly 1 in 10 women, and about half as many men, take antidepressants (Barber, 2008; Breggin & Breggin, 2010).

THIS JUST IN

Do Antidepressants Work Better Than Placebos?

Americans spend and spend on antidepressant drugs. Prozac, one popular antidepressant, attained annual sales of $800 million just a few years after its 1988 release (Stipp, 2005). Today, Americans shell out $10 billion a year on antidepressant medicines—

The exact answer depends on how “working” is defined. People who take antidepressants do improve compared with people who receive no treatment (no medication, no psychotherapy) for their depression. In this sense, then, antidepressants work. But as the psychologist Irving Kirsch (2010) emphasizes, this does not mean that the active ingredients in antidepressant drugs effectively reduce depression. The problem is that substances with no active ingredients whatsoever—that is, placebo substances—

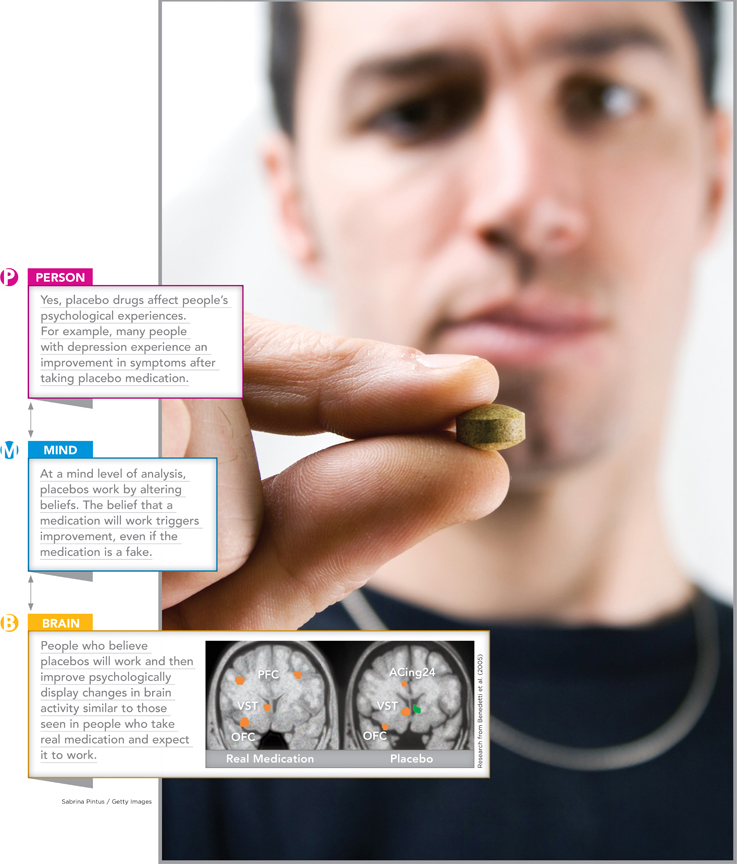

Placebo effects are fundamentally psychological, not biochemical (Kirsch, 2010). When people take prescribed substances, they expect them to work; the prescriptions give people hope. Hope combats the feelings of hopelessness that accompany depression. As a result, depressed people who take medication improve. This improvement occurs whether the drugs are real pharmaceuticals or placebos; both instill hope and reduce depression. Placebos can even induce changes in brain activity that resemble changes found in people taking real medication (Benedetti et al., 2005; Figure 15.3).

The key question, then, is whether antidepressant drugs work better than placebos. Kirsch (2010) reviewed all existing research studies on this question, and found the difference between drug effects and placebo effects to be remarkably small. Specifically, 82% of the effects of drugs were due to placebo effects. In other words, there was a unique effect of drugs, but it was only about 20% larger than the effect obtained from placebos. Even this 20%, Kirsch argues, is small. On a 52-

Others reach similar conclusions. One research team reviewed therapy outcomes among more than 700 individuals with mild, severe, or very severe levels of depression. Among people whose depression levels were very severe, antidepressant drugs were of substantial benefit. But for the remaining two-

THINK ABOUT IT

When a therapy works, ask why. What are its active ingredients—the components that actually caused it to succeed? Did a drug work because of its chemical substances or merely because taking a drug caused people to believe they would improve? Did people benefit from a psychotherapy strategy because of specific components of that strategy or merely because they had a warm, socially skilled individual (therapist) who was paying attention to them?

A final bit of evidence “just in” compares the effects of antidepressant medication to a simple intervention: exercise. Reviews of research findings indicate that, for mild to moderate levels of depression, a program of intense physical exercise is as effective as anti-

Like most people, I used to think that antidepressants worked.

—Irving Kirsch (2010, p. 1)

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 9

True or False?

Kirsch’s extensive review of research led him to conclude that most of the effectiveness of antidepressants is due to placebo effects.

A. B. Among the studies demonstrating that antidepressants work, the size of the effect was large.

A. B.

Because both drug therapies and psychotherapy are available to treat depression, a significant question for people experiencing the disorder is how the different therapy strategies compare. Much research has investigated this question. Findings commonly indicate either that cognitive therapy is superior to drugs in relieving major depression or that the two approaches are about equally effective (Butler et al., 2006; Cox et al., 2012). Drug therapy rarely is found to be superior. In light of recent findings comparing antidepressant drugs to placebo medications (see This Just In), this result is not surprising. Antidepressant medications have proven to be less effective than the pharmaceutical industry, and depression sufferers, had hoped.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 10

The following statement is incorrect. Explain why: “To be diagnosed with major depressive disorder, an individual has to exhibit all depressive symptoms (consistent depressed mood; loss of interest in most daily activities; change in body weight; change in sleep patterns; fatigue; feelings of worthlessness, hopelessness, or helplessness; difficulty concentrating; and thoughts of suicide) for at least two weeks.”

Question 11

Aaron Beck observed that individuals with major depression displayed a cognitive triad of negative thoughts about themselves, the world, and the . Research indicates that cognitive therapy is superior to, or at least equal to therapies in relieving the symptoms of major depression.

CULTURAL OPPORTUNITIES

Diagnosing Disorders

People in all cultures experience psychological disorders. But do they experience the same disorders?

In the United States, a particularly common disorder is major depression. As you learned in the main text, its central features are prolonged low mood and feelings of personal worthlessness and hopelessness.

You might expect that diagnoses of major depression would be common everywhere in the world. They aren’t. Research conducted in Hunan, a large province of South-

The difference in diagnostic categories used in the United States and China has two possible causes. People in the different countries may experience fundamentally different disorders. Alternatively, they may experience similar disorders but think and talk about them differently. Cultural differences may affect how people conceptualize their personal distress. Some evidence supports the latter view.

Researchers (Kleinman & Kleinman, 1985) carefully analyzed the psychological conditions of 100 Hunanese patients diagnosed with neurasthenia. The vast majority of them, they found, showed signs of major depression as it is diagnosed in the United States. In other words, even though they were diagnosed in China with neurasthenia, not depression, in the United States, major depression would have been the diagnosis.

What accounts for this discrepancy? It appeared that when the Chinese patients talked to their Chinese physicians, their conversations did not focus on the patient’s thoughts and emotional life. Rather, as in other non-

Thus, cultural factors shape the way health professionals discuss and diagnose the conditions of their patients.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 12

In Hunan, major is less likely to be diagnosed than in the United States, largely because of what the Hunanese about when describing their symptoms. They tend to focus on symptoms and not emotional ones because, in their culture, sadness is shameful.

Bipolar Disorder

Preview Questions

Question

What defines bipolar disorder and how prevalent is it?

What defines bipolar disorder and how prevalent is it?

What therapies effectively treat bipolar disorder?

What therapies effectively treat bipolar disorder?

“I have two moods. One is … rollicking … the wild ride of a mood. [The other] stands on the shore and sobs … Sometimes the tide is in, sometimes it’s out.”

The writer suffers from bipolar disorder, also known as manic-

Intense positive mood might sound like fun. But to people with bipolar disorder, both depression and mania bring difficulties (Gruber, 2011). In manic states, people sometimes engage in reckless behavior they later regret. It’s “a world of bad judgment calls,” the writer above continues. During the manic periods, “[I display] every kind of bad judgment because it all seems like a good idea at the time. A great idea. … So if it’s talking, if it’s shopping, if it’s—

Like J. K. Rowling, this writer also overcame her depressive disorder and achieved great professional success. She is Carrie Fisher—

In her memoir entitled Wishful Drinking, Carrie Fisher reacts to learning that her image graced the title page of an abnormal psychology textbook chapter on bipolar disorder: “Obviously my family is so proud. Keep in mind, though, I’m a PEZ dispenser and I’m in the Abnormal Psychology textbook. Who says you can’t have it all?” (Fisher, 2008, p. 114)

DEFINING FEATURES AND PREVALENCE. To be categorized according to the DSM as a person with bipolar disorder, an individual must display two types of symptoms:

Depression: One or more episodes of depression, that is, periods of at least two weeks during which a person experiences depressed mood, loss of interest in activities, fatigue, and feelings of worthlessness.

Mania: A period of at least four days in a row marked by abnormally high energy, racing thoughts, extreme talkativeness, high levels of self-

esteem, or involvement in fun activities that are costly or risky (e.g., the person decides, on a whim, to check into the most expensive hotel in town). Manic periods may also include episodes of extreme irritability.

These mood swings, from depression to mania and back, distinguish bipolar disorder from major depression. Note that a person with bipolar disorder generally will experience substantial periods of normal mood state; the deviations from this state are what characterize the disorder.

About 1% of adults suffer from bipolar disorder (NIMH, 2007). In terms of overall numbers of people, then, bipolar disorder is quite prevalent; in the United States alone, 1% of adults translates into about 2 million people. Bipolar disorder is a long-

TREATMENT. The primary form of treatment for bipolar disorder is drug therapy. The reasoning behind drug therapy is that bipolar disorder’s mood swings may stem from abnormal variations in brain functioning. The brain’s neurotransmitter systems generally are seen as the biological culprits (Nakic et al., 2010). Mood stabilizers, which are drugs designed to influence neurotransmitters in the brain in a manner that calms and steadies the patient’s swinging mood states, thus are a major form of treatment (Stahl, 2002).

Three types of drugs are most commonly used as mood stabilizers (Stahl, 2002):

Lithium: The drug lithium, a chemical compound that centrally includes the physical element lithium, is the classic drug of choice for treating bipolar disorder. Findings support its effectiveness. Lithium reduces bipolar symptoms, even in long-

term use among patients who take the drug for years (Tondo, Baldessarini, & Floris, 2001). Anticonvulsants: As we’ve seen, sometimes drugs used to treat one disorder turn out to benefit another. Anticonvulsants, which are drugs used to treat epileptic seizures, also reduce bipolar symptoms (Bowden, 2009).

Antipsychotics: As you’ll learn in the next chapter, a variety of drugs are used to treat psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia. Some of the more recently developed antipsychotic drugs also have been found to reduce bipolar symptoms (Perlis et al., 2006).

The best evidence that these drugs work comes from meta-

Major depression and bipolar disorder are not the only depressive disorders. In postpartum depression, which affects 10 to 15% of women who give birth (Pearlstein et al., 2009), women experience symptoms akin to those of major depression beginning within a few weeks of childbirth (NIHM, 2011). In seasonal affective disorder, individuals tend to experience depressed mood during late autumn and winter, periods when there is less sunlight (Rosenthal, 2009). Light therapy can help sufferers. Exposure to bright light for about half an hour a day relieves symptoms, an effect that may be due to the influence of intense light on neurotransmitters in the brain (Virk et al., 2009).

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 13

Which of the following statements are true of bipolar disorder?

It is marked by swings between depression, lasting at least two weeks, and mania, lasting at least four days in a row.

A. B. Its manic symptoms include a decrease in self-

esteem and an aversion to making decisions that are costly or risky. A. B. Only about .01% of adults suffer from it, making it one of the least prevalent medical disorders.

A. B. It is typically treated with mood-

stabilizing drugs, including lithium, anticonvulsants, and antipsychotics. A. B.