16.2 Personality Disorders

Preview Question

Question

What’s the difference between having a personality disorder and just being quirky?

What’s the difference between having a personality disorder and just being quirky?

The disorders you’ve learned about previously, in this chapter and in Chapter 15, disrupt people’s typical styles of behavior. Rather than being their usual selves, people become intensely anxious, or gloomily depressed, or begin hearing voices. Now we’ll consider a different type of disorder—

Personality disorders are chronic styles of thinking, behavior, and emotion that severely lower the quality of people’s personal relationships. These personal styles create conflict with others and, in the long run, harm the person with the disorder. People with personality disorders may not realize that the problems they experience in relationships are caused by their own behavior; as a result, they tend to blame others for interpersonal conflict.

People with personality disorders are particularly likely to experience difficulties when under stress. Stress can occur in different situations of a person’s life: work, relations with parents, social relationships, dealing with financial problems, and so forth. In general, it is good to be “flexible” when dealing with stress; that is, to develop different strategies for coping with different types of stress (Cheng & Cheung, 2005). However, people with personality disorders are relatively inflexible; their personal style is consistent across different situations. As a result, they do not cope with stress as effectively as most other people (Bijttebier & Vertommen, 1999).

Why do psychologists say that some personality styles are “disorders” rather than merely saying that a person is “unusual” or “quirky” or “difficult”? The term disorder implies that the personality style is directly harmful to mental health. Psychologist Theodore Millon (2004) explains that people with personality disorders contribute to their own psychological distress in a number of ways:

Inflexible interactions with a given person. If you’re in a relationship and find that certain behaviors of yours bother the other person, you might change how you act in order to improve the relationship. But people with personality disorders tend to maintain the same style of behavior, which creates ever-

increasing interpersonal stress. Inability to adapt to different people and roles. You probably act differently toward different people: family, friends, teachers, or a boss at work. You might politely follow an order from a job supervisor, but not a friend. People with personality disorders are less able to adapt to different people and roles. They often seek to control situations, rather than adapt to them.

As a result of this inflexibility, people with personality disorders do not grow psychologically, gaining in maturity, as others do. Instead, time and again, their inflexible behavior creates the same type of interpersonal conflict with others.

When the DSM is used to diagnose people, personality disorders are found to be remarkably prevalent. A large survey in the United States, involving a representative sample of more than 9000 adults, found that roughly 1 out of every 11 adults exhibits a diagnosable personality disorder (Lenzenweger et al., 2007).

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 9

In what ways do people with personality disorders contribute to their own distress?

They refuse to believe that their visual hallucinations are not grounded in reality, even if acknowledging this would improve interactions.

A. B. They inflexibly maintain the same style of interaction with a particular person, even if changing it would improve the relationship.

A. B. They do not change their behavior to suit the type of people with whom they are interacting, preferring instead to control situations.

A. B.

Types of Personality Disorder

Preview Question

Question

What characterizes the six main types of personality disorder: antisocial, avoidant, borderline, obsessive-

What characterizes the six main types of personality disorder: antisocial, avoidant, borderline, obsessive-

Identifying and distinguishing among personality disorders is a tricky task. DSM-

ANTISOCIAL PERSONALITY DISORDER. Antisocial personality disorder is defined by a set of negative personality traits. People with antisocial personalities are manipulative (using others to achieve their own goals), callous (not caring about harm to others), hostile (often angry and vengeful), and are risk takers (engaging calmly in dangerous behaviors). They lack empathy; that is, they are unconcerned about the feelings, rights, and safety of others. If a person displays these traits consistently, and they harm the individual’s interpersonal relationships, then the person meets DSM criteria for antisocial personality disorder.

The center point of antisocial personality disorder, at a deeper psychological level, is what Sigmund Freud called a weak superego (Meloy, 2007) and what contemporary psychological scientists refer to as moral reasoning (Raine & Yang, 2006). Most people adhere to moral rules that prevent them from harming others and motivate them to perform behaviors that are good for society. In antisocial personality disorder, these rules seem to be absent; people lack an inner “voice of conscience.” Even after harming another person, an individual with antisocial personality disorder experiences no guilt or remorse. Such people can be dangerous to themselves, to society at large, and to the therapists who try to help them. One therapist reports an antisocial personality disorder client saying, after numerous therapy sessions, “You know a lot about me, Doc, and sometimes when people know too much they get killed” (Meloy, 2007, p. 779).

People who fit the diagnostic category antisocial personality disorder are not all the same. The category is broad and, within it, researchers have identified distinct subgroups of people with somewhat different personalities (Poythress et al., 2010). One subgroup has a high level of a trait called psychopathy (Hare & Neumann, 2008). Psychopathy is a personality style defined not only by the hostility toward others and lack of guilt that characterize antisocial personality disorder in general, but also by a tendency to lie to others and manipulate them. Psychopaths are “social predators who charm [and] manipulate … leaving a broad trail of broken hearts, shattered expectations, and empty wallets” (Hare, 1999, p. xi). Many of the serial killers who have plagued recent world history displayed psychopathic characteristics (LaBrode, 2007). Psychopathy is less prevalent among women than men (Cale & Lilienfeld, 2002). By contrast, a different subgroup shows signs of antisocial personality disorder (a callous lack of empathy) but not psychopathy (manipulativeness and lying; Poythress et al., 2010).

Can you think of any fictional characters who could be characterized as psychopaths?

AVOIDANT PERSONALITY DISORDER. Consider the case of “Ms. K,” a 24-

Ms. K’s is a case of avoidant personality disorder, which is characterized by feelings of social inadequacy and low self-

Research suggests that, among people with avoidant personality disorder, feelings of insecurity are particularly acute in a certain type of situation: when others might be criticizing them. In one study (Bowles et al., 2013), participants were asked to imagine themselves working busily on particular projects and receiving feedback from others. In one experimental condition, the feedback was fully supportive (“I’m really impressed”). In another, it was ambiguous with a suggestion of criticism (“Don’t spread yourself too thin”). More so than other individuals, people with avoidant personality disorder felt badly about themselves after being exposed to the ambiguous feedback.

BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER. You encountered borderline personality disorder at the outset of this chapter, in our opening vignette. The 17-

Borderline personality disorder is the most commonly diagnosed personality disorder, with a prevalence rate of 2 to 3% of the adult population (Gunderson & Links, 2008). Borderline personality disorder is difficult to describe precisely; professionals are not in complete agreement on its defining characteristics. However, it has the following main features:

Unstable sense of self. People’s self-

image varies. Sometimes they seem self- confident, and other times they seem to have poor self- esteem. Rather than maintaining a stable set of personal goals and plans, their goals vary in a seemingly erratic manner. Emotional instability. Variations in self-

image are accompanied by variations in emotion. People with borderline personality disorder experience a range of negative emotions; sometimes they feel depressed and worthless, yet they also experience outbursts of anger. Unstable interpersonal relationships. People with borderline personality disorder experience extreme difficulties maintaining relationships. They tend to view friends and romantic partners in an extreme black-

and- white manner, sometimes seeing their partner as being a wonderful, ideal person, but other times experiencing intense disappointment in, and anger toward, that same person. Their relationships with others often lack empathy. Rather than understanding the emotional life of another person, people with borderline personality disorder use the relationships to bolster their own self- image and calm their own emotional troubles. Sense of abandonment. People with borderline personality disorder have recurring worries that other people will reject or abandon them.

This combination of symptoms is exceptionally stressful. Borderline individuals report feeling lonely, worthless, and overwhelmed by the stresses of life (Zanarini at al., 1998). They experience a spectrum of negative emotions and have difficulty controlling those emotions. Borderline individuals dwell on, or go over and over, their emotions. As a result, feelings of anger, anxiety, and despair can last for weeks and disrupt their lives (Conklin, Bradley, & Westen, 2006).

People with borderline personality disorder sometimes take desperate steps to escape this stress. One step is self-

THINK ABOUT IT

Sometimes a psychological disorder is defined by a set of symptoms that is unusually diverse, and professionals are not in full agreement about which symptoms go into that definition (as occurs in the case of borderline personality disorder). When this happens, is there really just one disorder? Or might there be two or more distinct types of disorders that professionals have yet to recognize?

Another tragic step taken by many borderline patients is suicide. Suicide is a risk associated with many mental health problems; different forms of distress and despair can drive people to the ultimate, final escape from life’s problems (Nordentoft, Mortensen, & Pedersen, 2011). Borderline patients, however, are particularly at risk. The majority of borderline patients attempt suicide, and 10% of individuals with borderline personality disorder die from their attempts (Soloff et al., 2005). Research sheds light on the reasons behind this act. Interviewers spoke with women who had tried unsuccessfully to take their own lives. They indicated that a primary reason for suicide was to make other people better off (Brown et al., 2002). Individuals with borderline personality disorder perceived themselves as a burden on others and tried to take their own lives to relieve others of this burden.

NARCISSISTIC PERSONALITY DISORDER. Narcissistic personality disorder is a personality pattern in which individuals are excessively self-

Narcissistic individuals possess personality characteristics that are contradictory (Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001). On the one hand, they hold views of themselves that seem extraordinarily positive. Narcissists crave attention and, when they get it, talk about how great they are. On the other hand, their opinion of themselves seems “fragile.” If you know a narcissist, you might get the impression that, down deep, the person isn’t confident in all the great things he’s saying about himself. This uncertainty, in fact, is why he craves attention. Narcissists need to find other people to support their grandiose, yet fragile, views of self. The political dictator who surrounds himself with “yes men” illustrates these personality dynamics.

OBSESSIVE COMPULSIVE PERSONALITY DISORDER. As you may recall, Chapter 15 discusses obsessive-

More than a century ago, the French psychologist Pierre Janet observed this OCD—

The observations of Janet, and many subsequent psychologists and psychiatrists, led to the recognition of obsessive-

Research reveals a strong relation between the personality disorder, OCPD, and the anxiety disorder, obsessive-

SCHIZOTYPAL PERSONALITY DISORDER. Schizotypal personality disorder is characterized by two predominant features. One is its distinctive patterns of thinking (Chemerinski et al., 2013). In this disorder, individuals have odd beliefs that diverge from those of most members of society; individuals may, for example, believe in “paranormal” phenomena, such as the ability of thoughts alone to control physical objects. They also may exhibit odd mannerisms, styles of dressing and speaking that differ from most other people, and suspiciousness of other people. People with schizotypal personality disorder are, in short, individuals whom you might call “eccentric.”

The second distinctive feature is that people with schizotypal personality disorder have few close friends (e.g., Bergman et al., 1996). Their odd personal style, combined with their suspicions of others, appear to undermine their capacity to form close personal relationships with people outside of their immediate families. Many people with the disorder lead lives that are socially isolated from others.

The odd beliefs that characterize this personality disorder are related to schizophrenia; the name itself, “schizotypal,” suggests that the disease is a type of schizophrenia. However, research on brain mechanisms in the two disorders suggests that they are distinct (Haznedar et al., 2004).

Table 16.2 summarizes the characteristics of the six disorders we have reviewed.

16.2

| Six Types of Personality Disorder | |

|---|---|

|

Personality Disorder |

Defining Characteristics |

|

Antisocial personality disorder |

Lack of empathy; disregard for others’ feelings, rights, and safety; manipulative, callous, and often hostile personality traits. |

|

Avoidant personality disorder |

Feelings of inadequacy and low self- |

|

Borderline personality disorder |

Unstable sense of self, unstable relationships, and unstable emotional life; feelings of abandonment and concern about being rejected by others. |

|

Narcissistic personality disorder |

Excessively self- |

|

Obsessive- |

Perfectionism, a desire for order and control over activities, and rigid adherence to rules; devotion to work may impair personal relationships. |

|

Schizotypal personality disorder |

Odd, eccentric patterns of thinking or behavior, combined with social isolation resulting from an inability to form close personal relationships with people outside of immediate family. |

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 10

People with personality disorder are often, among other things, manipulative and callous and engage in risky behaviors. Serial killers tend to be particularly high in the trait of , characterized by the tendency to lie and to manipulate. People with personality disorder seem very confident yet need others to support their grandiose views of themselves. Though a precise definition of personality disorder has not been attained, most can agree it is characterized by instability in self-

Causes of Personality Disorder: Nature, Nurture, and the Brain

Preview Questions

Question

How do nature and nurture contribute to the development of antisocial behavior?

How do nature and nurture contribute to the development of antisocial behavior?

Question

What does the psychopathic brain look like?

What does the psychopathic brain look like?

Question

How are the brains of people with borderline personality disorder different from those without the disorder?

How are the brains of people with borderline personality disorder different from those without the disorder?

Nature and nurture both contribute to the development of personality disorders. Genes and environmental experience play significant roles and interact with one other. Research on antisocial personality disorder illustrates this general point.

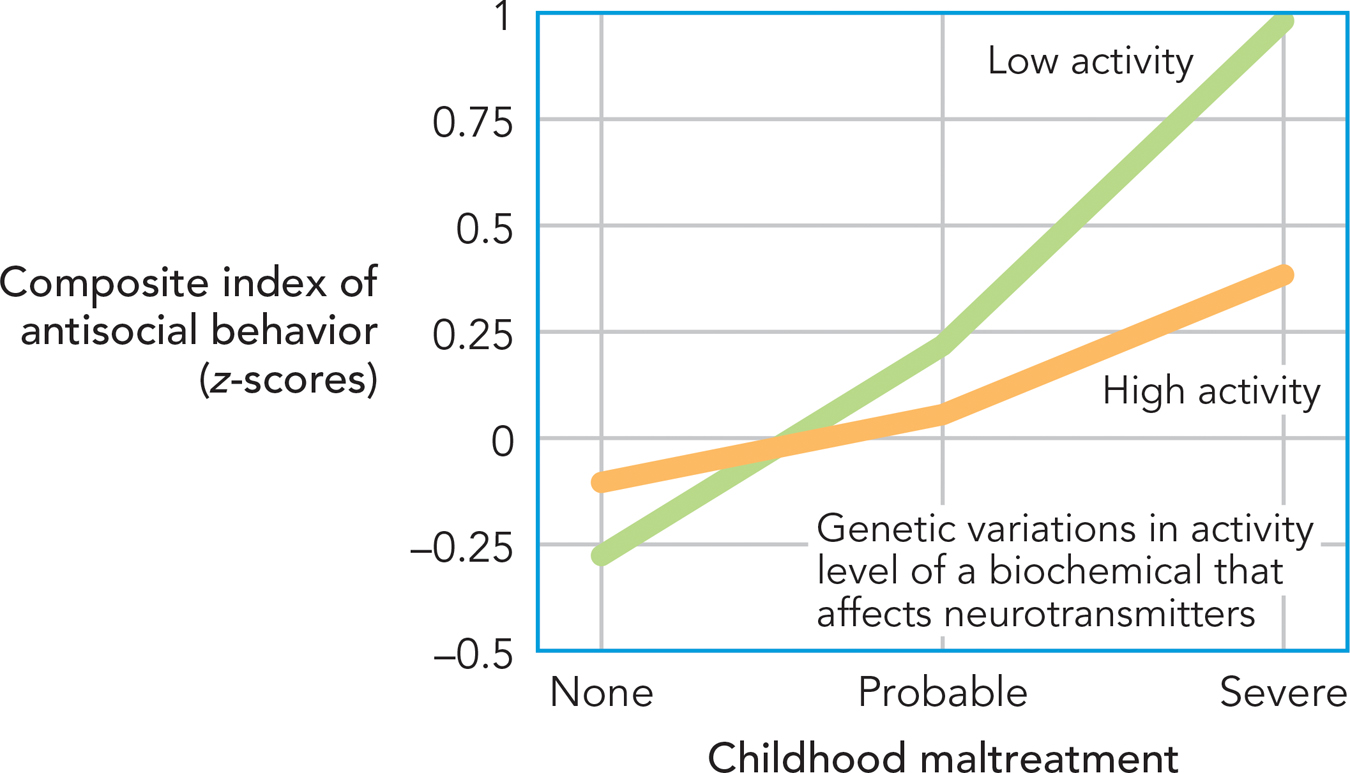

GENE–

This twin-

In this study, researchers (Caspi et al., 2002) focused on two factors, one environmental and one genetic:

Childhood maltreatment: The environmental factor was maltreatment during childhood. Maltreatment, which included harsh physical punishment and sexual abuse, was identified by interviewing parents and by speaking with their children years later, when they reached adulthood.

A gene that affects neurotransmitter levels: The genetic factor was person-

to- person variation in a gene that affects neurotransmitter activity in the brain. Specifically, the gene influences the body’s production of a biochemical that alters the chemical structure of neurotransmitters. Once altered, signaling activity in the brain is reduced.

These two factors have opposing effects within the brain. Childhood maltreatment is a highly stressful event that causes neurotransmitter activity to increase. The gene causes neurotransmitter activity to decrease; in particular, it enables the brain to return to a normal activity level after a stressful event occurs. Research findings show that these two factors combine in their influence on antisocial behavior. Among children who did not experience maltreatment, genetic variations did not make much difference. No matter what their genetic makeup, children who do not experience maltreatment are unlikely to develop antisocial personalities (Figure 16.7). However, among children who do experience maltreatment, genes make a big difference. Some of these children are quite likely to become antisocial adults, whereas others, who have a different genetic makeup, are not. Children who experience maltreatment, but who also possess genes that produce a biochemical that quickly restores their normal level of activity after stress, are “resilient” in the face of maltreatment (see Chapter 14); they are less likely to become antisocial adults.

CONNECTING TO STRESS AND COPING AND GENE-ENVIRONMENT INTERACTIONS

ANTISOCIAL AND PSYCHOPATHIC DISORDERS AND THE BRAIN. In addition to neurotransmitters, researchers studying the biology of antisocial personality disorder and psychopathy also investigate neurons, the brain’s cells. They compare people with different personality styles and search for neural differences.

A challenge is figuring out where in the brain to search. Psychological findings provide a clue. As you learned, the main psychological component of antisocial behavior is deficits in empathy and moral reasoning. Psychopathic individuals also display a lack of guilt feelings. Brain regions that already are known to be involved in these thoughts and feelings, then, are the place to look when conducting brain research.

In one study (Gregory et al., 2012), researchers examined a population of men who had been convicted of violent crimes (e.g., murder). Within this population, they identified one subgroup with antisocial personality disorder and psychopathic personality qualities, and a second with antisocial personality disorder but without psychopathic qualities. Brain scans revealed differences between the groups. The psychopathic group had lower brain volume in parts of the brain that are active when people (1) evaluate others’ ongoing social behavior and emotions (a region in the brain’s frontal cortex) and (2) relate ongoing behavior to personal memories and stored knowledge of social rules (a region in the temporal lobe). These brain regions are needed to understand when, and why, one’s own behavior violates social rules, and thus to experience emotions such as embarrassment and guilt (Gregory et al., 2012). The brain-

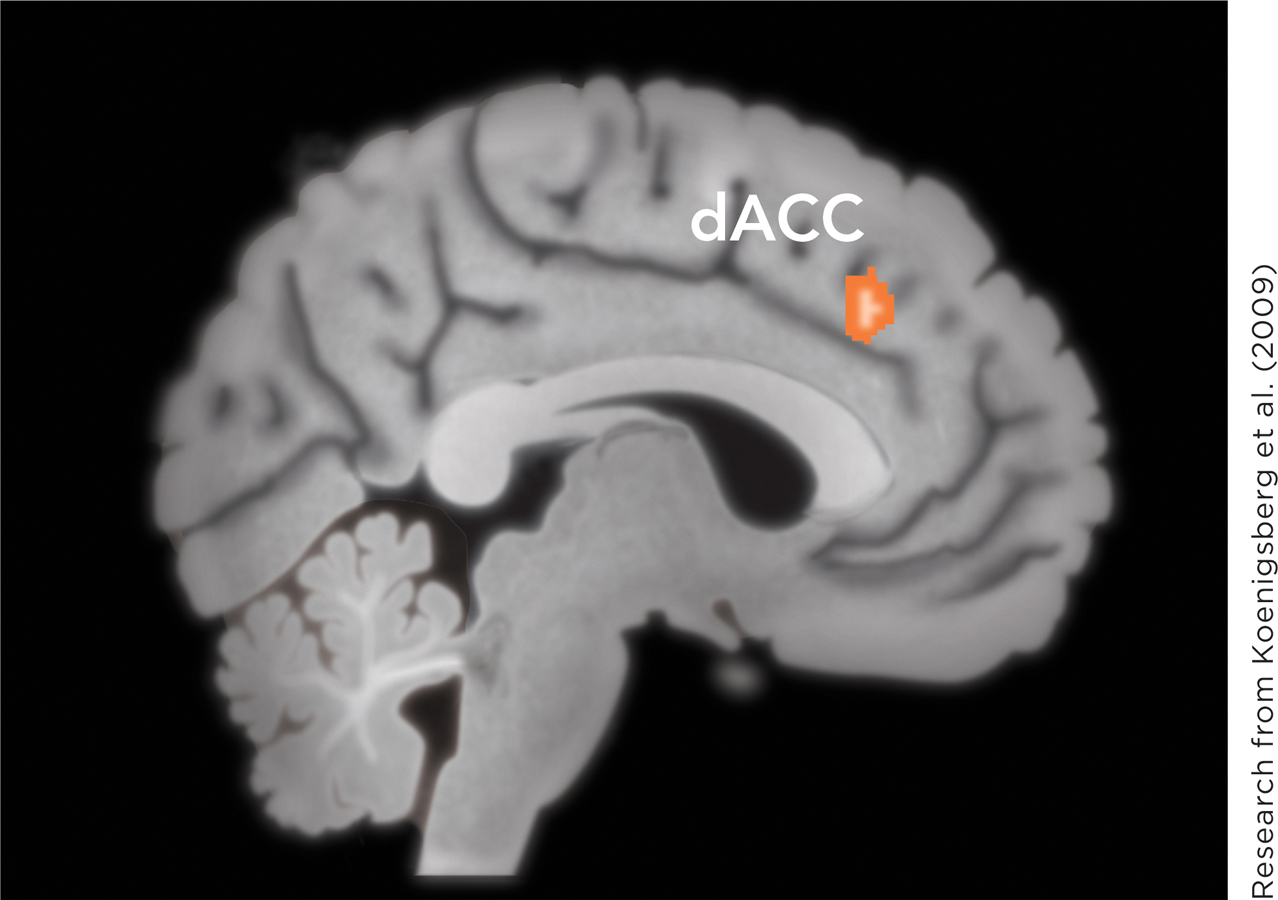

BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER AND THE BRAIN. Brain research sheds light on the biological underpinnings of other personality disorders, including borderline personality disorder. Researchers (Koenigsberg et al., 2009) asked two groups of people—

Brain activity in the groups differed. Variations were seen within the anterior cingulate cortex (Figure 16.8), a region known to be involved in emotional control (Ochsner et al., 2004). Compared with other people, in borderline patients, this brain region was less active (Koenigsberg et al., 2009).

What does this result say about borderline personality disorder and the brain? Actually, it’s hard to know precisely without additional research. There are two possibilities. Borderline patients may inherit a brain structure that is less developed and active. This would cause them to have less ability to control their emotions. Alternatively, it’s possible that borderline patients less frequently try to control their emotions. This could cause them to have less neural development in regions of the brain involved in emotional control (Giuliani, Drabant, & Gross, 2011). Behavioral activities (such as controlling emotions) can change the brain (see Chapter 3).

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 11

True or False?

A meta-

analysis of twin studies indicated that 59% of the differences in antisocial conduct were attributable to the influence of genes. A. B. Research by Caspi and colleagues indicated that the effect of genes on antisocial behavior was apparent only among those who had been mistreated as children.

A. B. Research indicates that among men who have antisocial personality disorder with psychopathic personality qualities, brain volume is lower in regions integral to feelings of embarrassment and guilt: one region associated with evaluating others’ emotions and another relating behavior to knowledge of social rules.

A. B. In one study, the anterior cingulate, an area associated with emotional control, was less active among those with borderline personality disorder.

A. B. Finding that the anterior cingulate is less active among those with borderline personality disorder enables one to conclude that these individuals were born with a deficit in this brain structure.

A. B.

Therapy for Personality Disorders

Preview Question

Question

How do therapists treat personality disorders?

How do therapists treat personality disorders?

When it comes to formulating therapy, personality disorders pose unique challenges. The disorders consist of emotional and behavioral patterns that are highly ingrained. There is no quick-

Despite the challenge, the need for therapy is compelling. In antisocial personality disorder, sufferers may inflict harm on others. In borderline personality disorder, people often inflict harm on themselves. Therapists need to act quickly to minimize the harm that these disorders can bring.

PSYCHOANALYTIC THERAPY AND COGNITIVE THERAPY. For many years, the primary psychotherapy for personality disorders was psychoanalysis (Waldinger, 1987). Psychoanalytic therapists focused on clients’ unconscious defense mechanisms (mental strategies to protect against anxiety; see Chapter 13) and their interpersonal relationship with the therapist. They judged that transference—

More recently, many therapists have employed cognitive therapy for personality disorders (Beck, Freeman, & Davis, 2004). In comparison to psychoanalysis, cognitive therapy places greater emphasis on conscious processes. Therapists believe clients are consciously aware of personal beliefs that contribute to their chronic psychological distress, and they try to modify these cognitions in therapy.

In addition, like psychoanalysts, cognitive therapists attend closely to the interpersonal relationship they have with their clients. In therapy for personality disorders, therapists must become familiar with a client’s life as a whole and must build a therapeutic relationship strong enough that the client will come to accept the therapist’s suggestions for significant personal change (Beck et al., 2004).

DIALECTICAL BEHAVIOR THERAPY. Psychoanalysis and cognitive therapy were not originally designed to treat personality disorders. Instead, they have been adapted to the need of the personality disorder client. We’ll now consider a therapy designed specifically to benefit clients with a personality disorder, specifically, borderline personality disorder.

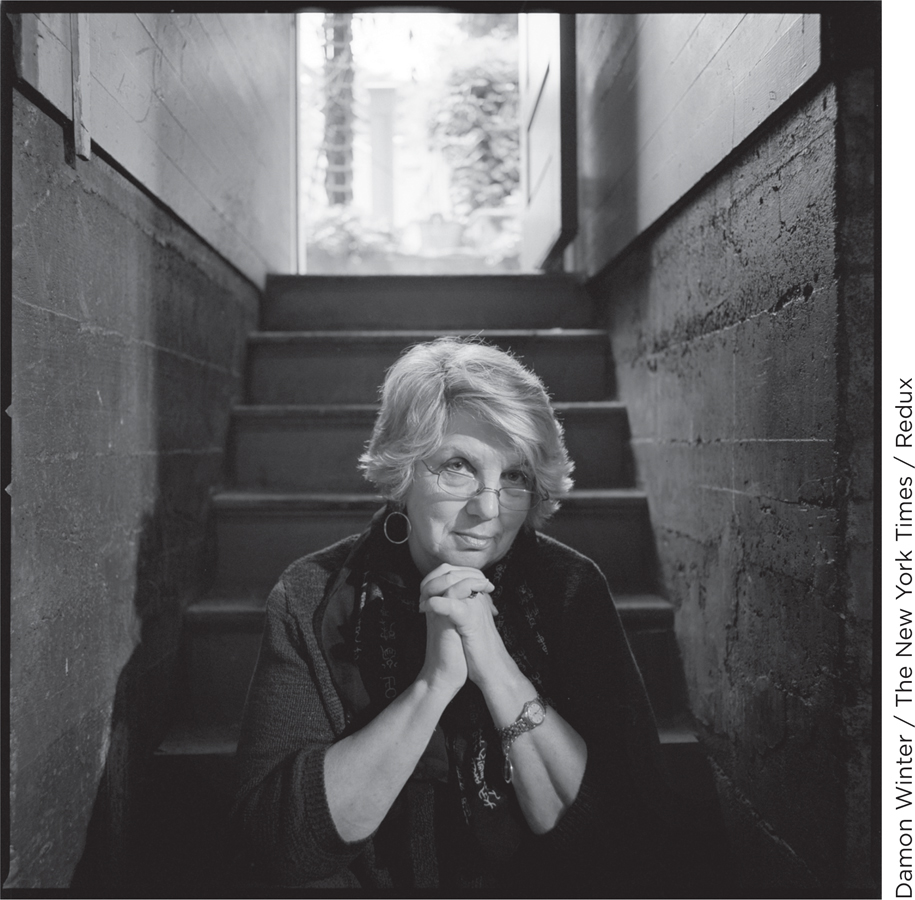

Dialectical behavior therapy is a treatment for borderline personality disorder developed by the psychologist Marsha Linehan (1993). Her therapy combines principles of behavior therapy with principles of Eastern and Western philosophy.

A primary philosophical principle is dialectic. Dialectic is a form of argument—

A second philosophical principle is acceptance. The term is used as in Zen Buddhism, where it refers to recognizing, and accepting, that some aspects of the world are unchangeable. This principle shifts the therapist’s focus. Rather than constantly striving for therapeutic change, the dialectical behavior therapist teaches clients to accept themselves, and their circumstances, as they are.

Linehan grafts these philosophical principles onto standard cognitive and behavior therapy practices. As in behavior therapy (see Chapter 15), the dialectical therapist strives to increase clients’ skills in problem solving and to reduce their anxiety. This is accomplished through both individual psychotherapy and group settings in which clients can develop and test their interpersonal skills (Linehan, 1993).

Good news for people with borderline personality disorder is that dialectical behavior therapy works. Numerous research studies comparing dialectical therapy to other treatments document that dialectic behavior therapy uniquely improves the emotional lives and behavioral experiences of borderline patients (Lynch et al., 2007). Critically, dialectical therapy also substantially reduces their risk of suicide (Linehan et al., 2006).

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 12

In therapy for personality disorders, therapists help patients become conscious of the beliefs that contribute to their distress. Dialectical behavior therapy is used to treat personality disorder. Dialectic refers to a type of , one in which the validity of two opposing viewpoints is acknowledged. The therapist searches for a third viewpoint that can the differences between the two. The Zen Buddhist principle of that some things cannot be changed is a major feature of dialectical behavior therapy.