16.3 Dissociative and Conversion Disorders

Let’s hear once again from some people on an Internet discussion forum.

“Earlier this week, my therapist and I were talking and he determined that maybe the reason why Megan got constantly depressed is because she wanted attention. I gave her some and she made weird requests throughout the day. When I got to bed, she asked for a plushie to sleep with. I got her one from our closet (she has like thirty from an amusement park).”

- Page 733

“[They’re] all so different. I think it depends on their age. … For example, I know that Skip has had lengthy discussions about how much he wants to race (someone) to see who can run faster. He’s a young child, so this is important to him.”

“Kyle and Hera are married. Axel is something of a family friend to them. Mark and Kyle have been friends for years. Hera seems to know everyone in the system, and most people respect her and obey pretty much everything she says.”

These reports seem so different from those written by people with schizophrenia, which you read earlier in this chapter. These people don’t report that God is speaking directly to them, that everyone else is a robot, or other such delusional beliefs. You might wonder what these stories about Megan, Skip, Kyle, and the others are even doing in a chapter on psychological disorders.

Here’s a hint: Megan doesn’t exist. Neither does Skip. The same goes for Kyle, Hera, and their friends. They don’t exist anywhere except within the minds of the writers (from http://www.psychforums.com/dissociative-

In this section of the chapter, we’ll learn about the dissociative disorders and will then complete our coverage of psychological disorders by reviewing a puzzling syndrome known as conversion disorder.

Dissociative Disorders

Preview Questions

Question

Do people with dissociative identity disorder truly have multiple independent personalities?

Do people with dissociative identity disorder truly have multiple independent personalities?

What causes dissociative identity disorder?

What causes dissociative identity disorder?

What defines depersonalization/derealization disorder?

What defines depersonalization/derealization disorder?

Can people completely lose their memory for who they are?

Can people completely lose their memory for who they are?

Dissociative disorders are a category of psychological disorders in which people experience profound alterations in their sense of personal identity, their conscious experiences of events, or their memory of their own past. Clinicians have identified a range of dissociative disorders; they include dissociative identity disorder, depersonalization/derealization disorder, and dissociative amnesia and fugue.

DISSOCIATIVE IDENTITY DISORDER. In dissociative identity disorder, people experience more than one self; that is, more than one personality seems to inhabit their mind. (The disorder was formerly known as multiple personality disorder.) According to the DSM, people qualify as having the disorder when they experience two or more personalities that are distinct. The different personalities are experienced as possessing different behavioral styles, emotional experiences, and personal goals. An additional factor in diagnosis involves memory. People with dissociative identity disorder experience memory disruptions; when in one personality state, they report being unable to remember what they were doing when in another.

Have you seen dramatic depictions of dissociative identity disorder on TV or film?

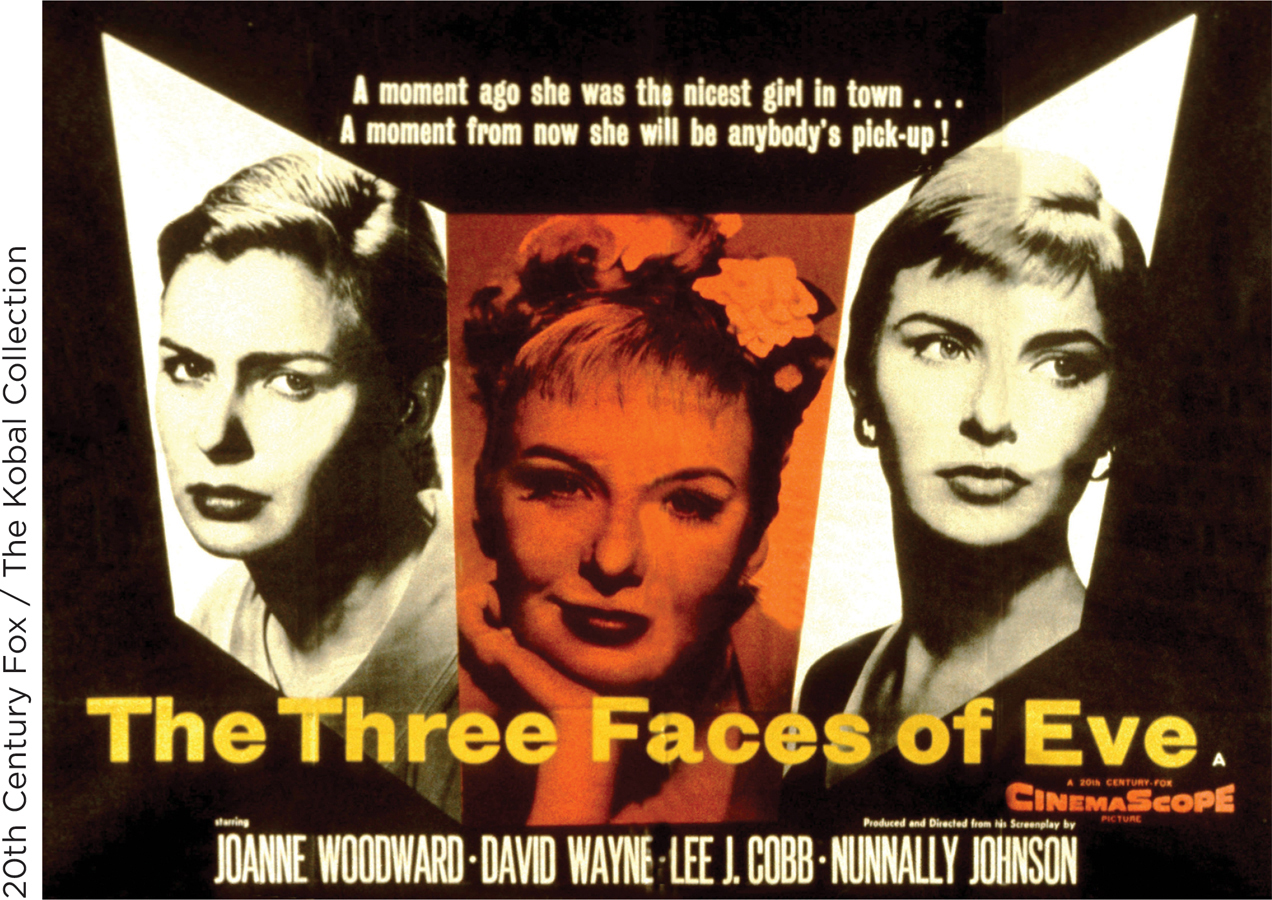

The disorder became well known in American society more than half a century ago thanks to a movie. The film The Three Faces of Eve (1957) told the story of Eve White, a modest woman with a wild alternative personality, as well as a third personality that was able to discuss the other two.

There can be no doubt that dissociative identity disorder severely disrupts people’s lives. Yet substantial questions about the disorder are unresolved (Gillig, 2009). One concerns the alternative personalities. Are they really separate psychological beings, each with its own, independent mental life? Or are they just ways of talking about normal variations in emotion and behavior (Merckelbach, Devilly, & Rassin, 2002)? Everyone is in a good mood sometimes and a bad mood other times. Everyone is fun-

A second question is the cause of dissociative identity disorder. Many clinicians have suggested that its causes lie in childhood (Gillig, 2009). Children who experience mistreatment, including sexual abuse, may cope with the trauma by convincing themselves that it happened “to somebody else”—an alternative personality. This was the explanation given in the famous case of Sybil (Schreiber, 1973), a woman whose multiple personalities reportedly were caused by physical abuse suffered at the hands of her mother (but see This Just In). Others, while recognizing the reality of the disorder, question whether evidence truly supports trauma-

THIS JUST IN

Sybil

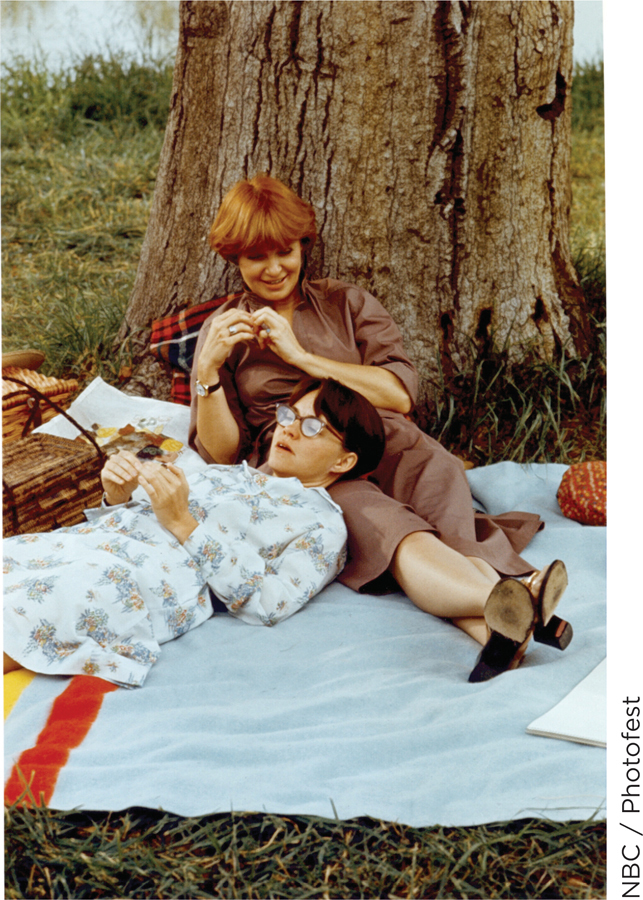

Dissociative disorder burst into the public awareness in the 1970s, thanks to psychology’s most famous case study of the past half-

Sybil’s therapist, a well-

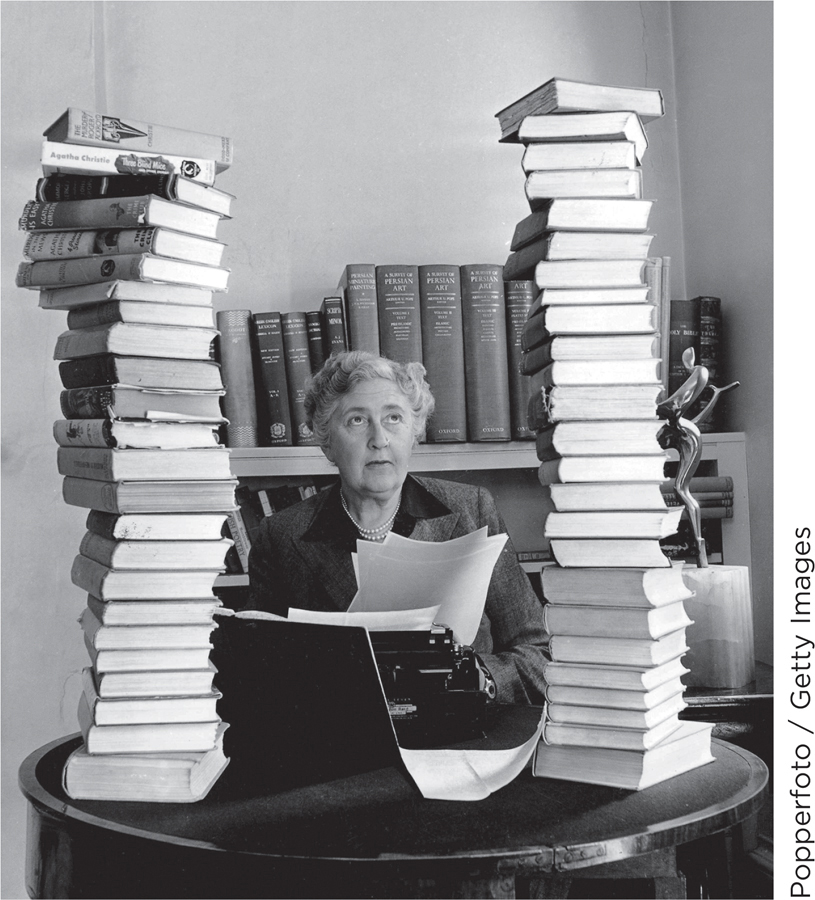

Dr. Wilbur and Sybil made her case public. They collaborated with a professional writer, Flora Rheta Schreiber, on Sybil: The True Story of a Woman Possessed by Sixteen Separate Personalities (Schreiber, 1973), a book detailing the childhood horrors that presumably gave birth to Sybil’s multiple personalities.

It sold like hotcakes. Although many professional books on mental health sell only a few thousand copies, Schreiber’s sold 6 million! Sybil the book was then turned into Sybil the TV miniseries, which was seen by 40 million Americans.

The case of Sybil affected society, including the mental health professions. Sybil made therapists and patients more aware of dissociative disorder. As a result, far more cases of the disorder were diagnosed after its publication than before. The case contributed to the inclusion of the disorder in the DSM. Wilbur and Schreiber appeared to have done a great service to mental health by uncovering facts about multiple personality … until the following news came in.

Much of the content of Wilbur’s and Schreiber’s report was a hoax. That was the conclusion reached by author Debbie Nathan, whose painstaking journalistic research has punched huge holes in the Sybil story. When she traveled to Sybil’s hometown and spoke with people who had known her family well, none reported any sign of child abuse. When she read correspondence between Sybil and Dr. Wilbur, she found a confession; Sybil had informed her analyst that she was “none of the things I pretended to be. … I do not have any multiple personalities. … I have been essentially lying. … I was trying to show you I felt I needed help.” Sybil had become emotionally dependent on her doctor, made up stories she thought her doctor wanted to hear, and explained to Wilbur that she had been afraid that if she told the truth, “you would be angry … [and] would not let me come to talk with you anymore” (Nathan, 2011, p. 106).

Incredibly, despite the confession, Wilbur remained certain that her original diagnosis of Sybil was correct! She stuck to her diagnosis of multiple personality disorder and worked to convince Schreiber that Sybil’s symptoms were real and that their causes were childhood abuse. Nathan’s journalistic detective work suggests that this book involved blatant deception, including the creation of a fake diary that told of Sybil’s mental distress in the years before she knew Wilbur.

Sybil truly was mentally distressed. But the bizarre details—

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 13

What motivated Sybil to lie to her therapist about her childhood trauma and to create 16 different alters?

There is no single, standard therapy strategy for treating dissociative identity disorder. Some therapists employ cognitive therapy designed to teach clients ways of coping with stress that are more adaptive than switching personalities (Gillig, 2009). Others use hypnosis (see Chapter 9) in an effort to help clients remain calm while focusing their attention on traumatic memories or feelings that may underlie their disorder (Kluft, 2012).

DEPERSONALIZATION/DEREALIZATION DISORDER. A second dissociative disorder is depersonalization/derealization disorder, which is defined by a change in people’s conscious experiences. In depersonalization/derealization disorder, people do not feel fully involved in their own experiences. They go through their day with strange detachment, as if they are merely observing the day’s events rather than taking part in them (Sierra, 2009). According to DSM-

Depersonalization: Feeling as if one is merely observing, in a detached manner, one’s ongoing thoughts and actions

- Page 736

Derealization: Feeling as if objects and other people are unreal; the world appears dreamlike or “foggy”

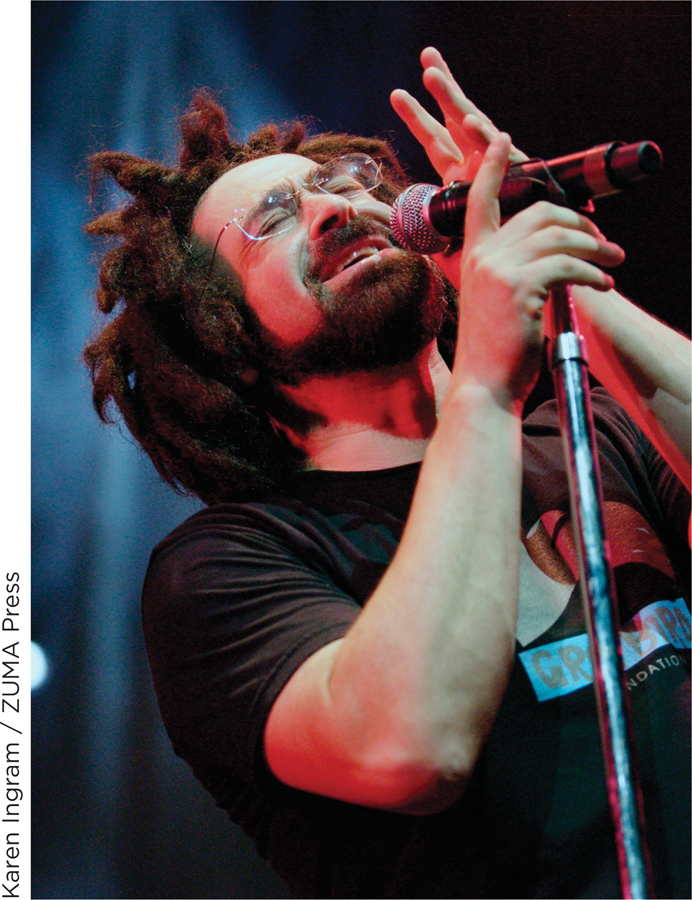

Adam Duritz, lead singer of the band Counting Crows, describes—

Not all cases of depersonalization are alike; there is a range of severity (Sierra, 2009). For some people, feelings of detachment occur only rarely and do not substantially disrupt their lives. For others, depersonalization/derealization experiences are nearly continual, and personal well-

DISSOCIATIVE AMNESIA AND FUGUE. The third dissociative disorder we’ll review disrupts memory. In dissociative amnesia, people are unable to remember significant personal information—

On rare occasions, individuals with dissociative amnesia experience dissociative fugue, which is a complete loss of memory for one’s own personal identity. Fugue states, when they occur, commonly prompt unexpected travel (the word fugue, in Italian, means “escape” or “take flight”). People move to a new location and may establish a new identity. When they recover memory of their original, true identity, they may have no memory of the fugue period. Cases of dissociative fugue are rare but have been documented, including among well-

Case study evidence shows what it’s like to experience dissociative amnesia and fugue. Consider these two cases:

A 27-

year- old businessman reported that, one morning, “When I woke up, I wondered what room I was in and where I was. I found my ID card in my wallet, which showed that I was a company businessman, but I was not otherwise aware of that fact” (Kikuchi et al., 2010, p. 603). “When a colleague was talking to [a 52-

year- old man] on the telephone, they both became aware of his retrograde amnesia. He could recall nothing about the company, his job, and events over the last few decades. He said afterward that he had thought, ‘Who am I talking to? What is that company?’” (Kikuchi et al., 2010, p. 605).

These two cases are particularly interesting in that they were reported by neuroscientists who used brain-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Match the disorder on the left with three facts about it on the right:

Question 14

|

1. Dissociative identity disorder |

a. May involve the feeling that things are dreamlike or unreal. |

|

2. Depersonalization/derealization disorder |

b. May have its origin in childhood trauma or could simply be an extreme manifestation of the different social roles a person adopts. |

|

3. Dissociative amnesia |

c. In rare cases, individuals experience fugue states that prompt unexpected travel. |

|

|

d. Characterized by a feeling of detachment from one’s own experiences |

|

|

e. Characterized by loss of memory for significant personal information |

|

|

f. Was once known as multiple personality disorder |

|

|

g. People question whether individuals with this disorder truly experience separate personalities |

|

|

h. Characterized by the feeling that objects and other people are not real |

|

|

i. Associated with decreased functioning of the hippocampus |

Answer: 1bfg, 2adh, 3cei

CULTURAL OPPORTUNITIES

Latah

Boo!

If you sneak up on people and yell, “Boo,” they will startle. The response is usually brief: a sudden wide-

In the Southeast Asian nation of Malaysia, however, some people display a response to startle, called latah (Simons, 1996), that might strike you as abnormal. A nineteenth-

O’Brien observed that startling stimuli—

Evidence suggests that, here in the twenty-

Latah can be understood, in part, in terms of biology. Throughout the world, some people experience larger startle reactions than others due to differences in the brain systems that produce the startle response (Dreissen et al., 2012). Within Malaysia, it’s likely such people are the individuals prone to experiencing latah. But culture is also critical. Latah is a culturally linked psychological syndrome; in other words, people only experience it if they grow up in cultures where it is an established and socially accepted pattern of response (Tseng, 2006).

What do you think of latah? It resembles dissociative disorders, in that conscious experience is altered and people’s normal personal identity escapes them. But is this a mental disorder?

This is the sort of question mental health professionals face when working with people from a culture unfamiliar to them. If people’s behavior seems strange, is it safe to conclude that they have a psychological disorder? In general, no. The behavior might be a normal reaction within the culture in which it originated. As one psychiatrist explained, “From a diagnostic point of view, it is necessary to be careful in labeling ‘peculiar behavior’ as a ‘disorder’ simply because it is unfamiliar. A good example is provided by … latah. (Many) behavioral scientists favor the view that latah is a social behavior and not a ‘disorder’ … even though some psychiatrists have considered it a psychopathological condition” (Tseng, 2006, p. 559).

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 15

In Malaysia, many individuals experience latah, a trance state following a response during which they imitate and obey those around them. Latah resembles disorders, but prior to concluding that it is a disorder, we should consider the context or in which it occurs.

Dissociative Disorders and the Law

Preview Question

Question

Are people with dissociative identity disorder responsible for crimes committed by their alternative personalities?

Are people with dissociative identity disorder responsible for crimes committed by their alternative personalities?

Dissociative identity disorder raises not only psychological questions, but also moral and legal concerns.

Sometimes we condemn behavior as immoral. We do this when the behavior violates a moral rule. What about behavior that violates a rule, but is performed by an alter —an alternative personality that seizes control of the actions of someone suffering from dissociative identity disorder? One sufferer writes, “One of my alters (a 17-

A similar question arises in legal settings (Farrell, 2011). Suppose a crime is committed, but the criminal, a person with dissociative identity disorder, reports the following: “I would never do that. I don’t even remember any of the criminal behavior. The crime wasn’t done by me. It was done by my alter.” Does this individual, who suffers from a severe mental illness, have the same legal responsibility as someone without a mental illness who planned and intentionally committed a crime?

Legal scholars have addressed this issue. Elyn Saks (featured in this chapter’s opening vignette) explains that a standard legal principle is the following: People are found innocent of acts if they “did not have the capacity … not to act” (Saks, 1991, p. 431; emphasis added). In other words, people with no control over their behavior cannot be found guilty. Imagine someone who is sleepwalking. If the person sleepwalks into a store and walks out without paying, she can’t be found guilty of shoplifting. Because she was asleep, she had no control over her behavior—

The psychologist John Kihlstrom (2005) notes a different legal circumstance. Suppose a person insists on his innocence in a criminal case, but one day an alter confesses to the crime. Should the legal system convict the person based on the confession of his alter?

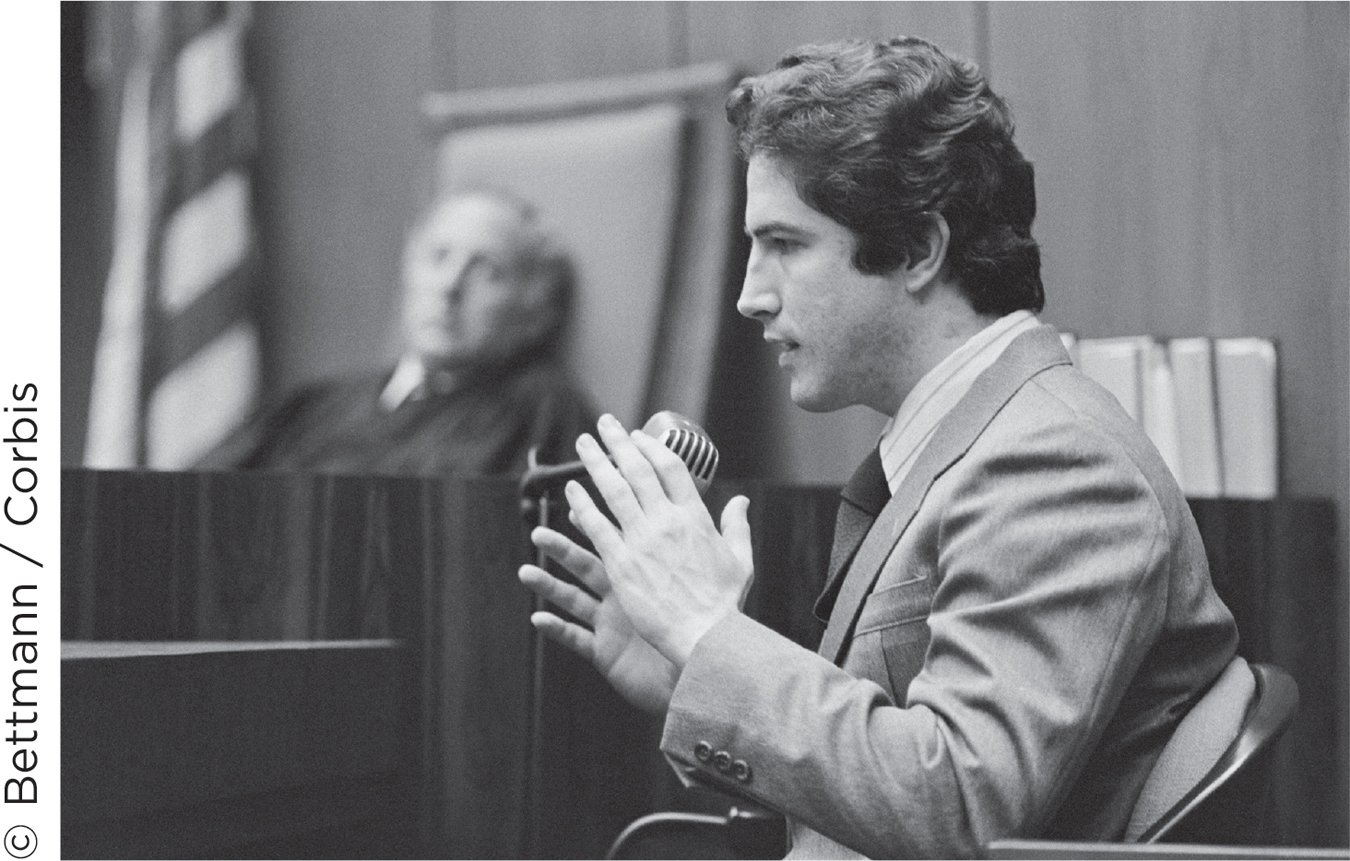

People charged with crimes have the legal option of pleading not guilty by reason of insanity. In the insanity defense, people admit to committing the crime—

How successful is this defense? Not very. The claim of insanity due to dissociative disorder rarely has produced not-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 16

The following statement is incorrect. Explain why: “The insanity defense works in the case of dissociative disorder because most courts are easily convinced the defendant is mentally ill and because they typically agree that this type of mental illness is a reasonable excuse.”

Conversion Disorder

Preview Question

Question

What could cause an individual to experience paralysis in the absence of a medical condition?

What could cause an individual to experience paralysis in the absence of a medical condition?

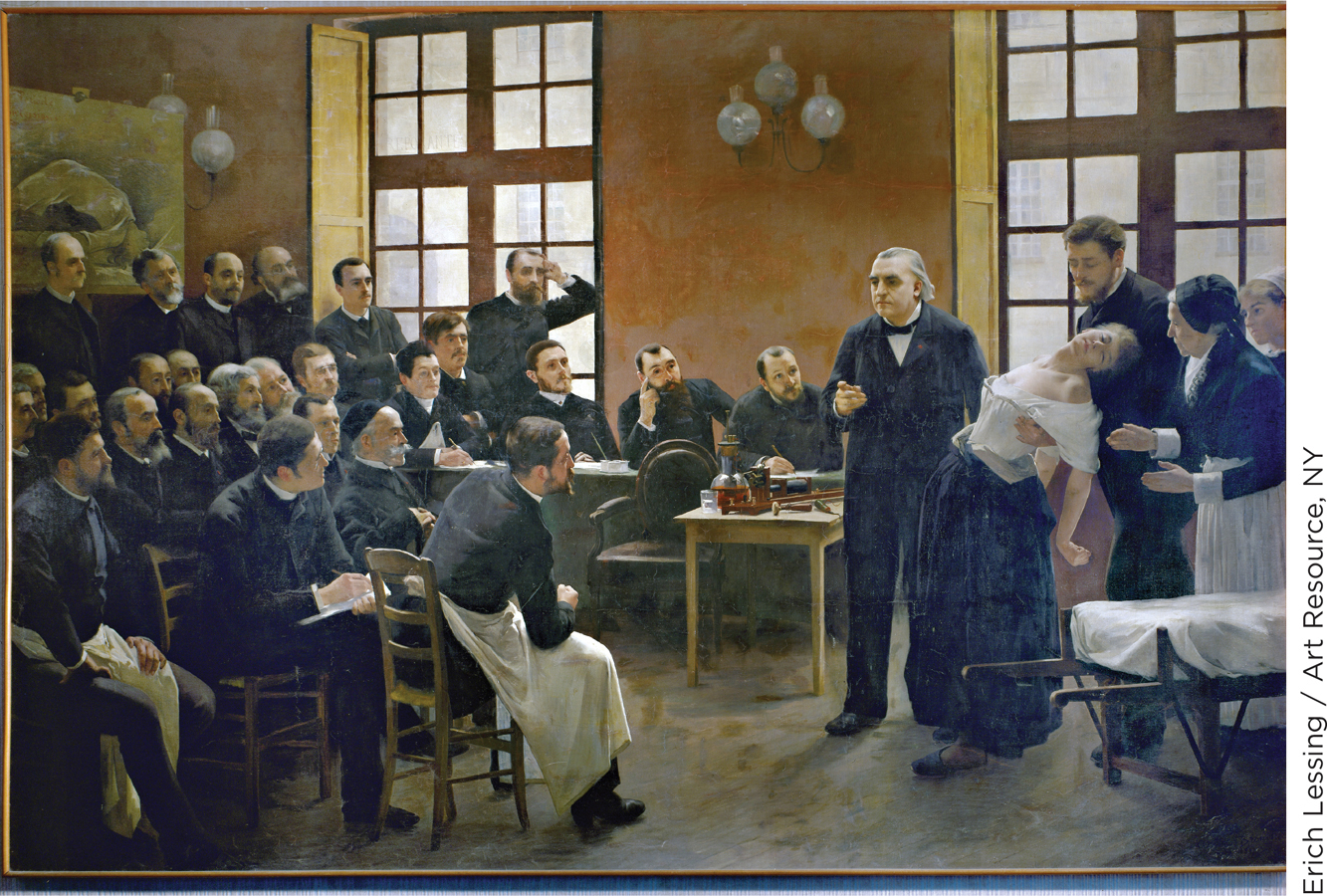

The last psychological disorder we will review, conversion disorder, is among the first to be studied systematically. Freud saw patients with the disorder in the late nineteenth century and based much of his psychoanalytic theory of personality on ideas about how conversion disorder develops and how it can be cured.

PHYSICAL SYMPTOMS AND EMOTIONAL DISTRESS. Conversion disorder is a psychological disorder in which people experience physical symptoms that cannot be explained by any medical condition. A person might report paralysis of a hand or arm, or difficulty seeing or hearing, without there being any detectable biological cause. Most editions of the DSM, including DSM-

Freud explained such cases through his theory of the unconscious. The unconscious mind, according to the founder of psychoanalysis, holds repressed ideas that the physical symptoms symbolically represent. A repressed traumatic memory that involved the use of one’s hand, for example, might cause a hand paralysis.

Today, most psychologists do not endorse Freud’s explanation of the disorder. In fact, some question the entire existence of conversion disorder. They say patients might be faking their symptoms to get attention from others, or might be overly sensitive to minor physical symptoms with ordinary medical causes. Recent brain-

CONVERSION DISORDER AND BRAIN RESEARCH. Researchers (Voon et al., 2010) studied patients with motor conversion disorder, in which the symptoms are motor movement disorders (e.g., muscular shaking) with no medical explanation. They compared them with a control group of psychologically healthy individuals lacking any sign of conversion disorder. The researchers took brain images while participants responded to a series of pictures displaying either fearful or happy human faces. Afterward, they conducted analyses to determine not only which brain regions were active during the task, but also how different regions of the brain interacted with each other during task performance.

The results provided remarkable brain-

OTHER PSYCHOLOGICAL SOMATIC DISORDERS. In DSM-

In somatic symptom disorder, people are excessively distressed about a physical symptom. Unlike conversion disorder, the cause of the physical symptom may be known; it may have a clear medical basis. The psychological problem is the person’s degree of reaction to the symptom. For example, a heart attack victim who has a medical prognosis predicting full recovery, but who obsessively worries about having another heart attack and substantially restricts work and social activities to avoid one, would be exhibiting somatic symptom disorder.

In illness anxiety disorder, a person is excessively distressed about his or her physical well-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 17

The following statement is incorrect. Explain why, briefly citing brain research: “All people diagnosed with conversion disorder are faking their symptoms.”

Question 18

In somatic symptom disorder and illness anxiety disorder, individuals are excessively stressed about physical symptoms; however, it is only in disorder that the individual has an actual physical symptom to worry about.