Background Texts

NEWS ARTICLE

Josh Higgins, “Student Turnout to Affect November Election” From Collegiate Times, April 11, 2012

Molly Reed has never registered to vote.

“I really just didn’t do it,” the freshman general engineering major said. “It was just because of lack of time, and I didn’t feel like doing it.”

Reed isn’t alone.

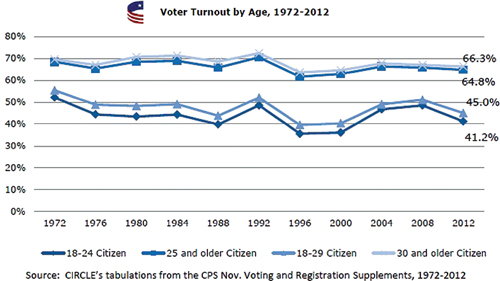

In the 2008 presidential elections, 51.1 percent of American citizens between ages 18 and 29 voted, according to a study by the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, or CIRCLE. While it was a 2.1 percent increase from the 2004 election and the highest turnout since 1992, youth turnout for elections has typically been lower than that of the older population.

The youth vote has increased in the past few years, but the CIRCLE study suggests voter registration laws affect turnout levels on Election Day. And with the 2012 presidential election fast approaching, registering to vote has become a priority for those wishing to cast a ballot on Nov. 6.

Where do students vote?

In Virginia, citizens are required to register 22 days before primary and general elections. But to register, students have to establish their permanent residency and complete registration forms, which has resulted in confusion over whether students should register in Blacksburg or in their hometowns.

“The actual law says a person must have an abode where they rest their head each evening,” said Randall Wertz, general registrar for Montgomery County. “Then they have their residency, or where they actually live.”

Wertz said students can determine whether they want to register at home or at school, as long as they use what they consider to be their permanent address on the registration form.

“We don’t treat students any differently than any other person,” Wertz said. “If they tell us in the application that is their primary residence, then that is what we utilize.”

Karen Hult, a professor and director of graduate studies in the political science department, confirms students’ ability to register at either location.

“I really think it’s a student choice,” Hult said. “But why would one choose to register here, when they can register back at home? It’s an interesting decision.”

Hult said some local residents, believing there is an effect on election outcomes from student involvement, do not like students participating in local politics.

“In the town of Blacksburg, I’ve not seen much evidence of any effect because I don’t think there’s been much of a turnout,” Hult said. “I was very disappointed at the level of apparent mobilization, activity, and interest here in the fall 2011 elections.”

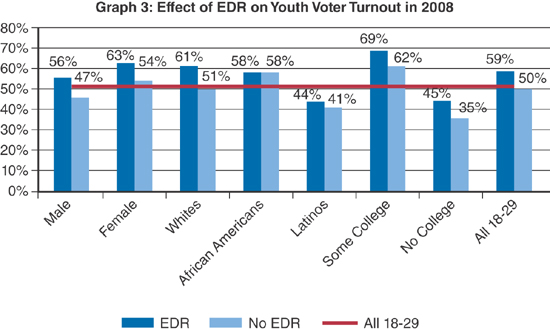

Voter registration rules, the CIRCLE study says, can influence turnout rates. According to the study, youth turnout in elections was 14 percentage points higher if Election-

In Virginia, there are restrictions on absentee voting, and citizens are not allowed to participate in in-

While voter registration requirements do have an effect on turnout, the issue for college students remains the decision to register at school or in their hometown. If a student decides to vote at school, Wertz said, they should be aware of possible consequences of changing their permanent address.

“Most students who have registered with us consider their address at the university as their permanent address, and that’s what they put on the form,” Wertz said. “It’s a choice of the student. If there are any ramifications for stuff like (tax dependencies and scholarships), we’re not interested in those aspects of it. The only thing we’re interested in is their permanent address.”

The issue with a student changing their permanent address is there’s a possibility tax dependencies and scholarships could be affected.

For example, if a student has a scholarship for living in their hometown, and they change their permanent address to their school address for voting purposes, there is a possibility they could lose the scholarship because they are no longer considered residents of their hometown.

Student political involvement

As the 2012 election approaches, political advocacy and voting registration, as well as its impact on college localities, will become prominent issues on college campuses.

Hult said while some local residents are concerned student participation might skew local elections, there could potentially be positive outcomes from student engagement.

“If there were more attention (to local elections and issues), there might be a better way to build bridges between the two communities,” Hult said. “Right now, I would guess that many of the town officials would say something like, ‘We would like students to be more involved. We would like to work with and talk to students.’ But we’ve not seen persistent evidence of that happening.”

Hult said since the 2008 presidential election, she had not seen much involvement from college students locally.

“This is a distinctly unengaged, uninvolved campus, compared to other places I have been,” Hult said. “There hasn’t been much visible activity on campus.”

However, that doesn’t mean everyone is politically apathetic.

Tara Dillard, a senior natural resources conservation major, is politically involved.

“I am registered to vote,” she said. “I think having the ability to have a say in who is in government is special and important.”

Hult said the geography, history, and demographic of the students that attend Virginia Tech could be a factor in campus disengagement in politics.

Voter turnout in the last election

The 2008 election was different.

“I think it was one of those years you had really riveting candidates, terrific mobilization campaigns, and some issues people cared about a lot,” Hult said, “issues like the economy, jobs, and Iraq.”

The 2008 election saw one of the highest turnouts in recorded history, according to the CIRCLE study. Young blacks posted the highest turnout rates ever observed for any racial or ethnic group of young Americans since 1972. Almost 55 percent of women between ages 18 and 29 voted in the elections, as well.

In addition, voter turnout of young people with college experience was 62 percent — a visible effect at Tech.

“It was stunning to see the lines of people waiting to go vote various places around town,” Hult said. “But we had people at some of the local polling places that stood in line for hours to cast a ballot.”

The 2008 election, Hult said, saw a moment in history where candidates, especially on the Democratic side, were able to mobilize youth and minority groups. She said Barack Obama, as the first black president, was able to mobilize the black vote, while Hillary Clinton attracted the woman vote.

In addition, she said Obama’s way of dealing with people in a “riveting and persuasive” way played a large role in his ability to galvanize the electorate.

However, one of the greatest influences on the election — especially on the youth vote — was the ability to capitalize on social media sites, like Facebook and Twitter.

“The drive to mobilize and register (the youth vote) and getting them involved in other ways made the difference,” Hult said. “I think it’s getting them involved in other ways — local service work, registering voters, talking about problems.”

The Obama campaign committed a lot of its grassroots effort on engaging and informing citizens through social media, Hult said, giving him an advantage in the race. However, she said he will likely not have that advantage in the upcoming election.

“I think social media will still be important for the president, but it’s no longer a new thing,” she said. “And all the Republicans are doing a good job with (social media) too. He’s still good, but he won’t be that much better.”

However, she said family members losing jobs during the economic recession also played a role in voter turnout. But she said dissatisfaction with the president’s lack of change and boredom with politics might affect the political landscape for 2012.

Voter turnout in the upcoming election

As the 2012 election looms, political scientists question whether this year will see the same youth voter turnout. Hult said while she considers Tech to be an uninvolved campus right now, certain factors might lead to a close race and political activism on campus.

While it is unclear whether turnout will meet or surpass that of 2008, Hult said a close race in Virginia might rally the party bases into coordinating active campaigns on campus.

“It looks like there’s going to be a race (in Virginia) again,” she said. “That should mobilize college campuses, and it may be that, once a Republican nominee is selected, that in the fall, I would expect to see a lot more engagement and involvement.

“I would look for the kind of mobilization on college campuses to be similar to 2008 — great use of social media, but especially in states like Virginia, which is up for grabs again.”

And with first lady Michelle Obama and Sen. Mark Warner speaking at Tech’s commencement in May, there could be a resulting political buzz on campus.

“Both of them understand this is a commencement speech, not a partisan speech,” Hult said. “That puts all kinds of constraints on the reaction there might be. What could get people more focused, though, is that kind of reaction (of commencement speaker selection) from students and parents. That sense of opposition might mobilize some Warner and Obama supporters on the one hand, and similarly the opponents on the other hand.”

While she said this is one possibility, she expressed that it could also have another effect.

“What it will do is get news cameras on campus and have people asking questions to students and getting them to think hard about what their answers are,” Hult said. “And to that extent, it could have a longer term impact, but we’ll see how students react.”

Hult said often portrayal of politics disengages citizens — even college students.

“I understand not everyone is excited (about politics),” she said. “I also understand people are increasingly becoming disaffected with what we see on cable TV and what we see cast as politics. I have to say I’m disturbed by it. I don’t think everything can be reduced to sound bites or just two sides. That can turn people off of politics. I don’t think all of politics has to be about conflict, yet that seems like what we want it to be.”

While Reed has not registered to vote, she said she plans to change that.

“I plan on doing it,” she said. “I just haven’t gotten around to it. It really just wasn’t at the top of my list of things I needed to get done before college.”

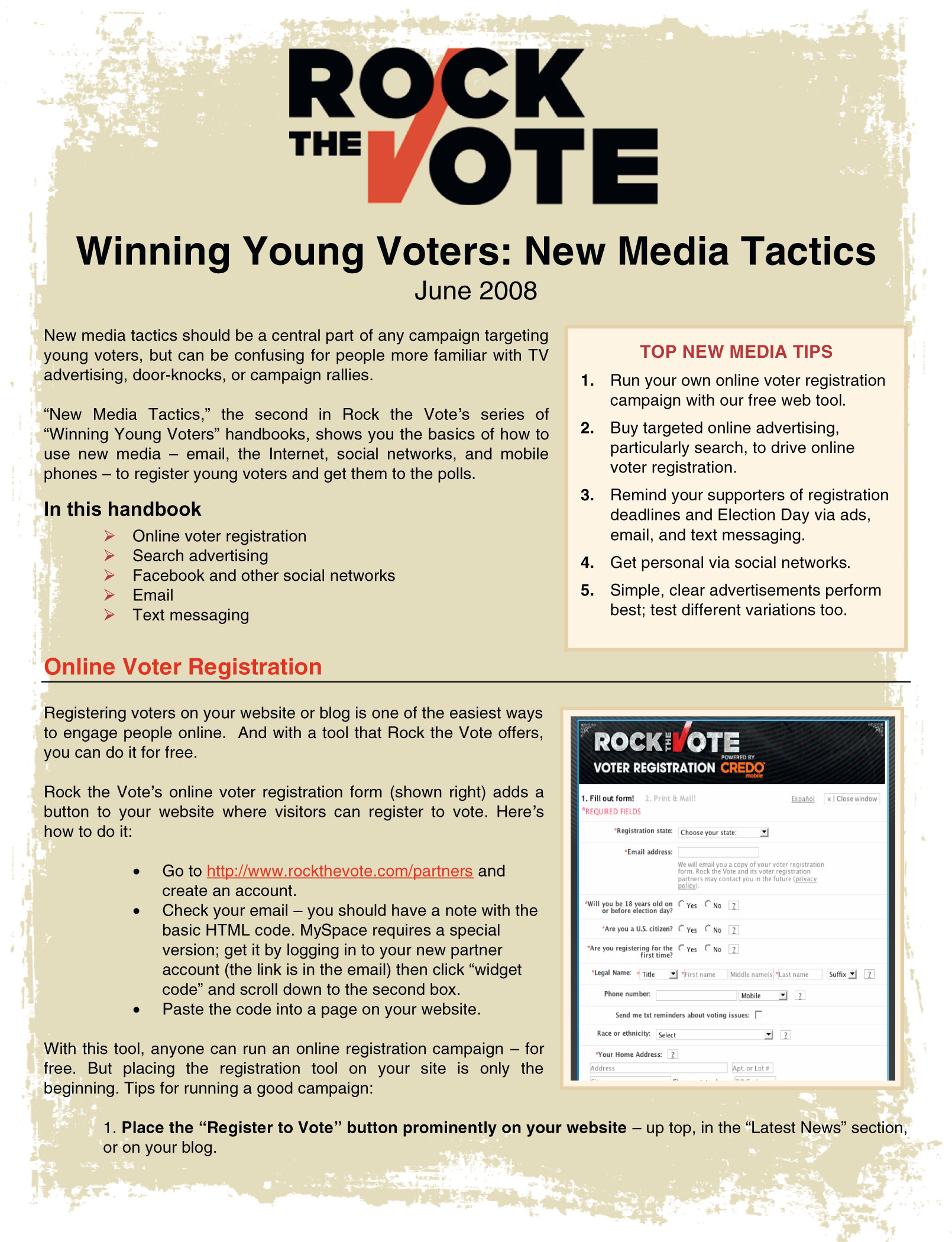

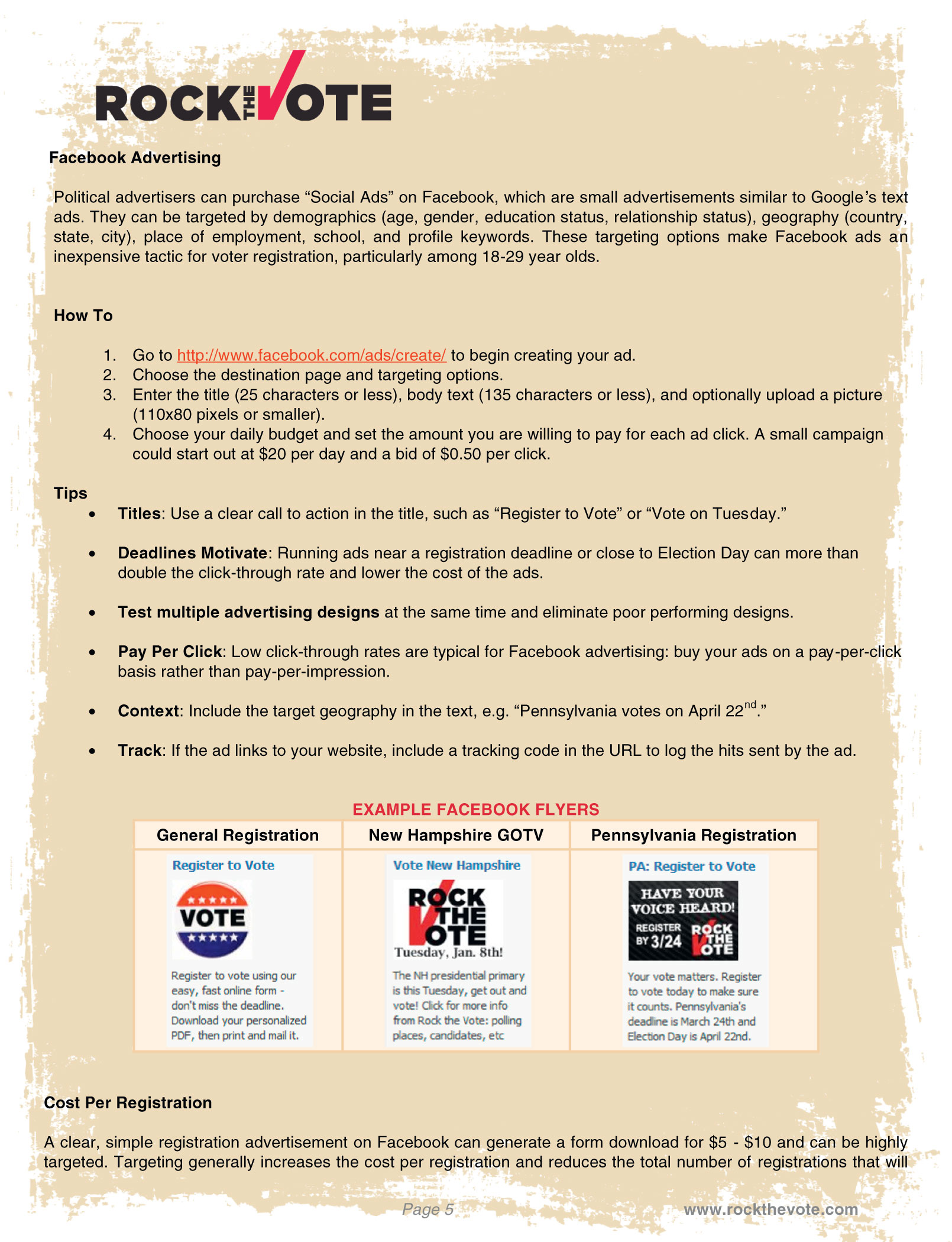

HANDBOOK

Rock the Vote, Winning Young Voters: New Media Tactics From rockthevote.org, June 2008

Rock the Vote is a nonpartisan group that provides research and resources for encouraging young people to participate in the election process. It published this brief handbook on its website in advance of the 2008 presidential election.

FACT SHEET

Center for Information Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE), Quick Facts — Youth Voting From civicyouth.org, 2013

Affiliated with Tufts University, CIRCLE conducts studies on civic education and civic engagement among youth. Many of its reports are condensed into fact sheets like the one below and published in the “Quick Facts” area of the group’s website.

The 2012 youth vote

- 45% of young people age 18–

29 voted in 2012, down from 51% in 2008. - In states with sufficient samples, youth turnout in 2012 was highest in Mississippi (68.1%), Wisconsin (58.0%), Minnesota (57.7%), and Iowa (57.1%). Voter turnout in 2012 was lowest in West Virginia (23.6%), Oklahoma (27.1%), Texas (29.6%), and Arkansas (30.4%).

- There were differences in the youth vote by gender and marital status. In 2012, 41.1% of single young men turned out, compared to 48.3% of young single females. In 2012, nearly 52.5% of young married females voted, compared to 48.5% of married men.

- The youth vote varied greatly by gender and race. Young Black and Hispanic women were the strongest supporters of President Obama.

- Although 60% of U.S. Citizens between the ages of 18–

29 have enrolled in college, 71% of young voters have attended college, meaning that college- educated young people were overrepresented among young people who voted. - In 2012, young voters 18–

29 chose Barack Obama over Mitt Romney, 60% to 37% — a 23- point margin, according to National Exit Polls.

Why youth voting matters

- 16Voting is habit-

forming: when young people learn the voting process and vote they are more likely to do so when they are older. If individuals have been motivated to get to the polls once, they are more likely to return. So, getting young people to vote early could be key to raising a new generation of voters. - Young people are a major subset of the electorate and their voices matter:

- 46 million young people ages 18–

29 years old are eligible to vote, while 39 million seniors are eligible to vote - Young people (18–

29) make up 21% of the voting eligible population in the U.S.

- 46 million young people ages 18–

- Involving young people in election-

related learning, activities, and discussion can have an impact on the young person’s household, increasing the likelihood that others in the household will vote. In immigrant communities, young voters may be easier to reach, are more likely to speak English (cutting down translation costs), and may be the most effective messengers within their communities.

And there are major differences in voter turnout amongst youth subgroups, which may persist as these youth get older if the gaps are not reduced.

What affects youth voting

- Contact! Young people who are contacted by an organization or a campaign are more likely to vote. Additionally, those who discuss an election are more likely to vote in it.

- Young people who are registered to vote turn out in high numbers, very close to the rate of older voters. In the 2008 election, 84% of those youth 18–

29 who were registered to vote actually cast a ballot. Youth voter registration rates are much lower than older age groups’ rates, and as a result, guiding youth through the registration process is one potential step to closing the age- related voting gap. - Having information about how, when, and where to vote can help young people be and feel prepared to vote as well as reduce any level of intimidation they may feel.

- A state’s laws related to voter registration and voting can have an impact on youth voter turnout. Seven out of the top 10 youth turnout states had some of the more ambitious measures, including Election Day registration, voting by mail (Oregon), or not requiring registration to vote (North Dakota).

In 2008, on average, 59% of young Americans whose home state offered Election Day Registration voted; nine percentage points higher than those who did not live in EDR states. For more on state voting laws see: “Easier Voting Methods Boost Youth Turnout”; How Postregistration Laws Affect the Turnout of Registrants; State Voting Laws and State Election Law Reform and Youth Voter Turnout.

- 17Civic education opportunities in school have been shown to increase the likelihood that a young person will vote. These opportunities range from social studies classes to simulations of democratic processes and discussion of current issues. Unfortunately, many youth do not have these civic education opportunities, as research has shown that those in more white and/or more affluent schools are more likely to have these opportunities.

- A young person’s home environment can have a large impact on their engagement. Youth who live in a place where members of their household are engaged and vote are more likely to do so themselves.

What Works in Getting Youth to Vote

- Registration is sometimes a larger hurdle than the act of voting itself. Thus showing young people where to get reliable information on registration is helpful.

- Personalized and interactive contact counts. The most effective way of getting a new voter is the in-

person door- knock by a peer; the least effective is an automated phone call. - The medium is more important than the message. Partisan and nonpartisan, negative and positive messages seem to work about the same. The important factor is the degree to which the contact is personalized.

- Canvassing costs $11 to $14 per new vote, followed closely by phone banks at $10 to $25 per new vote. Robocalls mobilize so few voters that they cost $275 per new vote. (These costs are figured per vote that would not be cast without the mobilizing effort).

- Begin with the basics: information. Telling a new voter where to vote, when to vote, and how to use the voting machines increases turnout.

- Talk to them! Leaving young voters off contact lists is a costly mistake. Some campaigns still bypass young voters, but research shows they respond cost-

effectively when contacted. - For more information: Young Voter Mobilization Tactics; The Effects of an Election Day Voter Mobilization Campaign Targeting Young Voters by Donald P. Green.