Chapter Introduction

After studying this chapter you should be able to:

- Define and describe competitive labor markets.

- Derive a supply curve for labor.

- Describe the factors that can change labor supply.

- Describe the factors that can change labor demand.

- Determine the elasticity of demand for labor.

- Determine the competitive market equilibrium for labor.

- Describe Becker’s theory of economic discrimination.

- Describe the concept of segmented labor markets and how they affect wage levels.

- Describe federal laws and policies regarding discrimination.

- Describe the history, costs, and benefits of trade unions.

Mark Cunningham/MLB Photos via Getty Images

Did you see where some baseball player just signed a contract for $50,000 a year just to play ball? It wouldn’t surprise me if someday they’ll be making more than the President.

QUOTE FROM 1955

Some professions, such as baseball, try to maintain their traditions, but salaries for Major League Baseball players certainly have not remained the same. The average professional athlete did not used to be a multimillionaire. In 1964, the average salary in Major League Baseball was a mere $14,000 (about $100,000 in current inflation-adjusted dollars), suggesting that professional athletes back then chose their careers for the love of the game rather than as a way to become rich. Today, the labor market for professional athletes has changed. With lucrative advertising revenue and broadcasting rights, professional sport has become big business. In 2012, companies spent $28.6 billion for advertising in all U.S. sports. The World Series between the San Francisco Giants and the Detroit Tigers alone generated over $150 million, impressive considering only four of seven games were played, as the Giants swept the series.

Because the labor market demand for athletes is so great, professional sports leagues need to pay much higher salaries than they did 50 years ago in order to encourage the very best athletes to seek a career in sports. The result of this increase in demand in the labor market is a dramatic rise in salaries. In 2012, the average salary for a Major League Baseball player was $3,440,000, with the top earning player, Alex Rodriguez, earning $29 million. Even relatively unknown players, such as Kyle Blanks and Ramiro Peña, made over $480,000, the minimum salary in Major League Baseball in 2012. The president of the United States makes $400,000 a year. Indeed, the prediction from 1955 came true…for every player in the major leagues!

This chapter and the next begin our analysis of input markets, also called factor markets. Up to this point in the book, we have focused on product markets, mentioning input markets only incidentally. Sitting behind the production of goods and services, however, are inputs: workers, machinery, and manufacturing plants. Few firms can operate without employees or capital. Similarly, few households could survive without the income that work provides. Fortunately, many of the tools we introduced for the product market, such as demand and supply analysis, apply the same way in input markets. The main difference, however, is that in input markets, firms demand inputs whereas in product markets, firms supply goods and services.

This chapter focuses on the analysis of labor markets. The first two sections look at competitive labor markets, where the participants—firms and employees—are price takers. We then take a closer look at several situations in which wages are not set by competitive markets: instances of economic discrimination, and the economic effects of labor unions.

Your Wages and Your Job After College

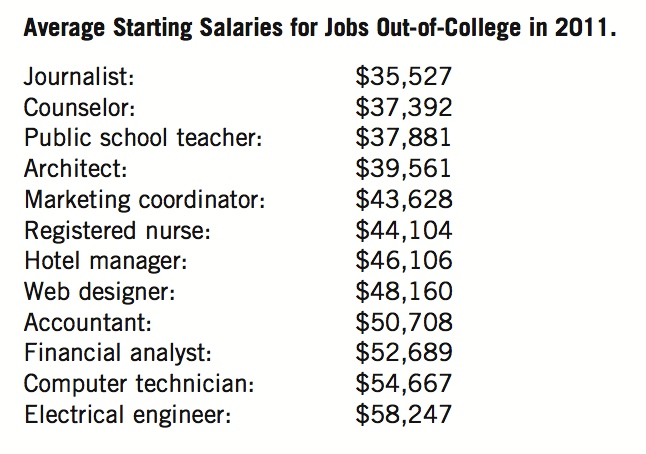

College students face important career decisions once they graduate. Some choose to pursue a professional or graduate degree, while others choose to venture into the labor force. One of the key factors influencing this decision is the wages offered to college graduates.

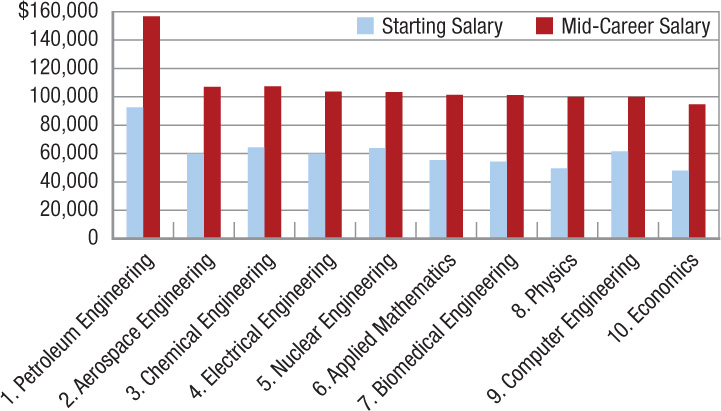

Choosing the right major in college can lead to a higher paying job. Economics is among the top 10 highest earning undergraduate majors out of a total of 128 majors surveyed. Studying economics can be interesting and lucrative!

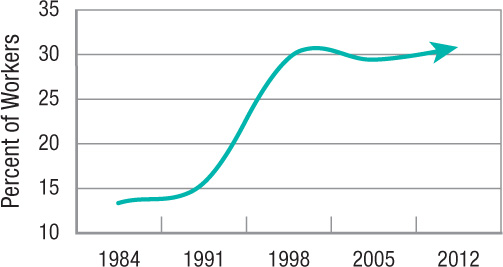

Careers with flexible working hours (“flextime”) increased in the 1980s and 1990s and have since leveled off. Today, three in ten full-time workers in the United States have flexible work schedules.

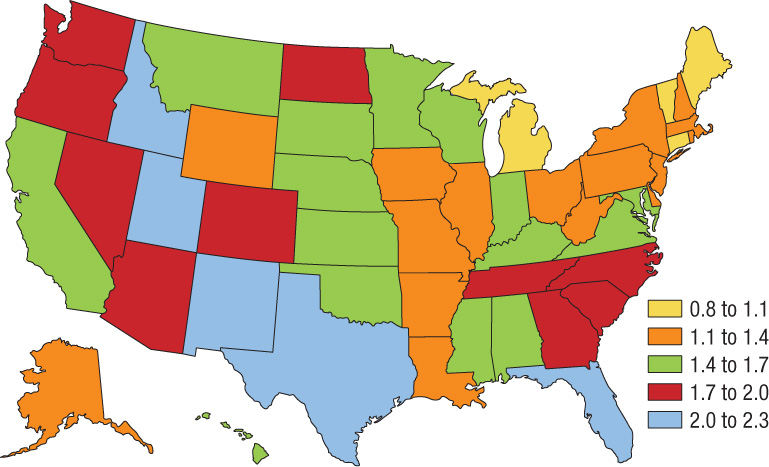

Projected annual job growth (in percent) through 2017 is shown by state. States with the highest projected job growth include Idaho, Texas, Utah, New Mexico, and Florida.

Competitive labor markets are similar to competitive product markets. We make several key assumptions. First, we assume that firms operate in competitive industries with many buyers and sellers, a homogeneous product, and easy entry and exit. A second assumption of competitive labor markets is that workers are regarded as equally productive, such that firms have no preference for one employee over another. Inhumane as it sounds, labor is treated as a homogeneous commodity. Third, a competitive labor market assumes that information in the industry is widely available and accurate. Everyone knows what the going wage rate is, therefore well-informed decisions about how much labor to supply are made by workers, and firms can wisely decide how many workers to hire.

A firm’s demand for labor is a derived demand; it is derived from consumer demand for the firm’s product and the productivity of labor. The labor supply, on the other hand, is determined by the individual preferences of potential workers for work or leisure. Like all competitive markets, supply and demand interact to determine equilibrium wages and employment.

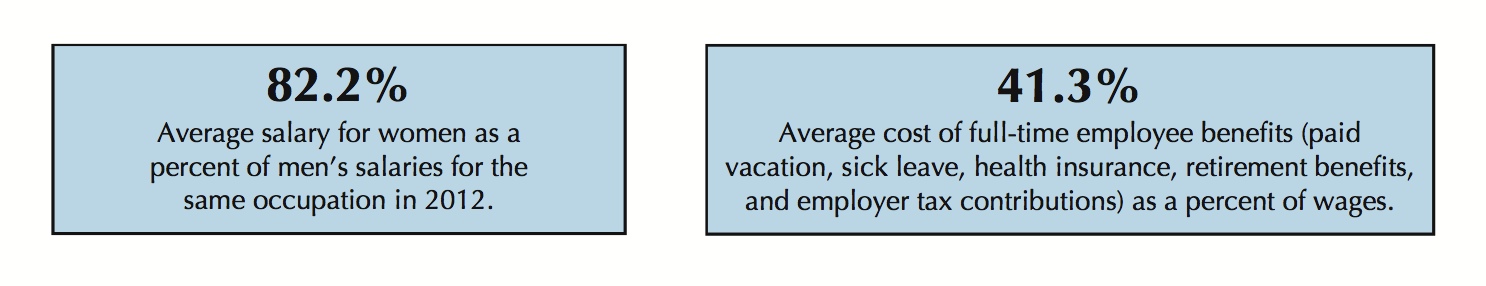

Following the analysis of the competitive labor market, we then ask why some people make more than others. Although differences in occupation and skill levels play a dominant role in determining wages, how often are wage differences the result of discrimination against people of a certain race, ethnicity, or gender?

Another reason for differences in wages is the role of unions. Unions are legal associations of employees that bargain with employers over terms and conditions of work. Unions use strikes and the threat of strikes to achieve their goals. The Major League Baseball Players Association is a powerful union, which negotiates salaries and benefits on behalf of its members. Sometimes disputes between the players union and team owners have resulted in strikes. In 1994–1995, a long strike led to a very short baseball season. Without the union, today’s baseball players might not all be making more than the president of the United States.