Monopsony

A monopsony is a market with one buyer or employer. The United States Postal Service, for instance, is the sole employer of mail carriers in this country, just as the armed forces are the only employers of military personnel. Single-employer towns used to dot the American landscape, and some occupations still face monopsony power regularly. Nurses and teachers, for example, often have only a few hospitals or local school districts for which they can work.

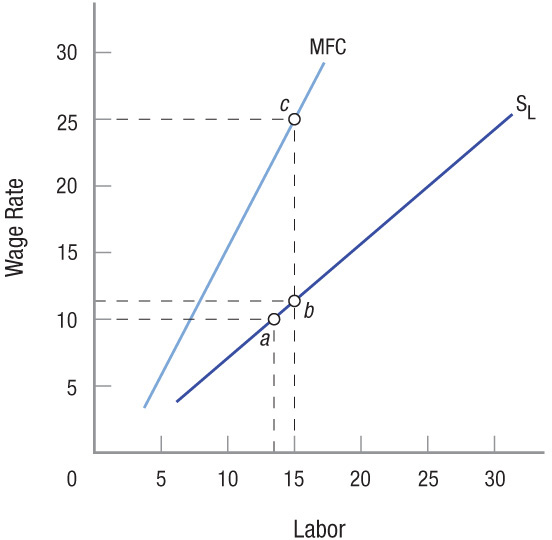

Because a monopsonist is the only buyer of some input, it will face a positively sloped supply curve for that input, such as supply curve SL in Figure APX-2. This firm could hire 14 workers for $10 (point a), or it could increase wages to $11 and hire 15 workers (point b). Because the supply of labor is no longer flat, however, as it was in the competitive market, adding one more worker will cost the firm more than the new worker’s higher wage. But just how much more?

FIGURE APX-2

Marginal Factor Cost This monopsonistic firm faces a positively sloped supply curve, SL. The firm could hire 14 workers for $10 an hour (point a), or it could increase wages to $11 an hour and hire 15 workers (point b). Since the supply curve is positively sloped, however, adding one more worker will cost the firm more than the cost of a new worker. To hire an added worker requires a higher wage, and all current employees also must be paid the higher wage. Therefore, the total wage bill rises by more than just the added wages of the last worker hired. The marginal factor cost curve reflects these rising costs.

marginal factor cost (MFC) The added cost associated with hiring one more unit of labor. For competitive firms, it is equal to the wage; but for monopsonists, it is higher than the new wage (W) because all existing workers must be paid this higher new wage, making MFC > W.

monopsonistic exploitation of labor Occurs when workers are paid less than the value of their marginal product because the firm is a monopsonist in the labor market.

Marginal factor cost (MFC) is the added cost associated with hiring one more unit of labor. In Figure APX-2, assume that 14 workers earn $10 an hour (point a), and hiring the 15th worker requires paying $11 an hour (point b). Assume that you decide to go ahead and hire a 15th worker. When you employed 14 workers, total hourly wages were $140 ($10 × 14). But when 15 workers are employed at $11 an hour, all workers must be paid the higher hourly wage, and thus the total wage bill rises to $165 ($11 × 15). The total wage bill has risen by $25 an hour, not just the $11 hourly wage the 15th worker demanded. The marginal factor cost of hiring the 15th worker, in other words, is $25 per hour. This is shown as point c. Because the supply of labor curve is positively sloped, the MFC curve will always lie above the SL curve.

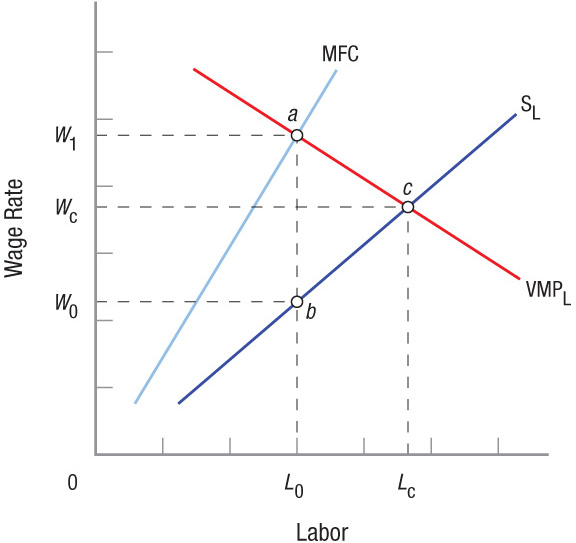

How does being a monopsonist in the labor market affect the hiring of a firm that is competitive in the product market? The monopsonist shown in Figure APX-3 is a competitor in the product market and has a demand for labor equal to its VMPL. This firm faces the supply of labor, SL. It will hire at the level where MFC = VMPL (point a), thus hiring L0 workers at wage W0 (point b). Note that these L0 workers, although paid W0, are actually worth W1. Economists refer to this disparity as the monopsonistic exploitation of labor. Again, the term is loaded, but to economists it describes a situation in which labor is paid less than the value of its marginal product.

FIGURE APX-3

Competitive Firm in the Product Market That Is a Monopsonist in the Input Market The monopsonist in this figure is a competitor in the product market and has a demand for labor equal to its VMPL, while facing supply of labor, SL. The firm will hire at the level where MFC = VMPL (point a), hiring L0 workers at wage W0 (point b). Note that these L0 workers, although paid W0, are worth W1. This is called the monopsonistic exploitation of labor. Note also that the wages paid in this monopsony situation (W0) are less than those paid under competitive conditions (WC), and that monopsony employment (L0) is lower than competitive employment (LC).

Note that the wages paid in the monopsony situation (W0) are less than those paid under competitive conditions (WC), and that monopsony employment (L0) is similarly lower than competitive hiring (LC). As was the case with monopoly power, monopsony power leads to results that are less than ideal when compared to competitive markets.

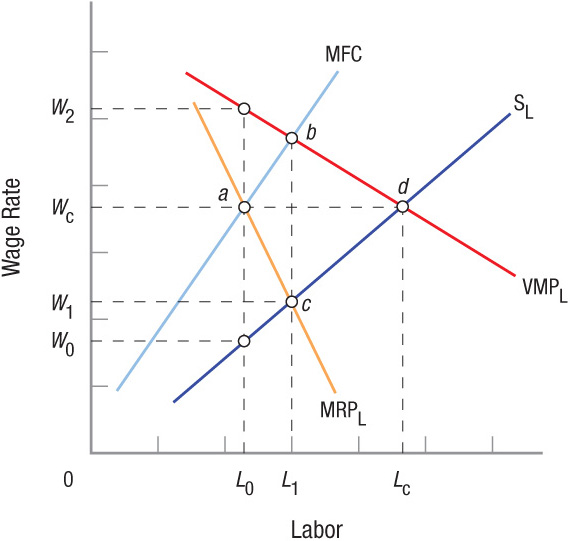

To draw together what we have just discussed, Figure APX-4 portrays a firm with both monopoly and monopsony power. The firm’s equilibrium hiring will be at the point where MFC = MRPL (point a), and thus the firm will hire L0 workers, although at wage W0. Note that this is the lowest wage and employment level shown in the graph. If the firm only had monopsony power, it would hire L1 workers (point b) at a wage of W1, which is higher than W0. If the firm only had monopoly power, it would also hire L1 workers for wage W1 (point c). Both of these employment levels and wage rates are less than the competitive outcome of LC and WC (point d).

FIGURE APX-4

Monopolist Firm in the Product Market That Is a Monopsonist in the Input Market This firm has both monopoly and monopsony power. The firm’s equilibrium hiring will be at the point at which MFC = MRPL (point a), and thus the firm will hire L0 workers, although at wage W0. Note that this is the lowest wage and employment level shown in the graph. If the firm only had monopsony power, it would hire L1 workers (point b) at a wage of W1. If the firm only had monopoly power, it would also hire L1 workers for wage W1 (point c). Both of these employment levels and wage rates are less than the competitive outcome of LC and WC (point d).

KARL MARX (1818–1883)

“Working men of all countries unite!” With this exhortation, Karl Marx ended his seminal Communist Manifesto, neatly summing up both his philosophy and his view of the world.

Karl Marx was born in Germany in 1818, but spent much of his adult life in England. By the time of his death in 1883, Marx and Friedrich Engels had crafted the essence of communism—the last ideology to seriously challenge capitalism in the 20th century. In their two major works, The Communist Manifesto (1848) and Das Kapital (1867), Marx and Engels offered a severe critique of capitalism and extolled the virtues of proletariat rebellion.

To preserve their privileges, the ruling class had always striven to oppress the underclasses. Marx saw a struggle between the bourgeoisie (or property owners) and the proletariat (the working class). This exploitation—the essence of capitalism—not only kept the bourgeoisie in power, but it also alienated the proletariat from its own labor, which to Marx was the true essence of all economic value. The only prescription to cure the monopolistic and monopsonistic exploitation of labor was proletariat revolution.

The key lesson to remember here is that competitive input (factor) markets are the most efficient, because inputs in these markets are paid precisely the value of their marginal products, and the highest employment results. This translates into the lowest prices for consumers at the highest output, assuming efficient production. Thus, just as competition is good for product markets, so too is it good for labor and other input markets.

IMPERFECT LABOR MARKETS

- When a firm is a monopolist in the product market and hires labor from competitive markets, the firm will hire labor at the point which the marginal revenue product is equal to the competitive wage.

- Monopolistic exploitation results because the monopolist pays less than the value of the marginal product of labor.

- Monopsony is a market with one employer. A monopsonist that sells its product in a competitive market hires labor at the point where the value of the marginal product is equal to the marginal factor cost.

- Monopsonistic exploitation occurs when the monopsonist pays labor less than the value of its marginal product.

QUESTION: Are public schools in rural areas a monopsony? Do they set wages in a way that is different from how wages are set in large urban areas?

Yes, they are monopsonists when it comes to hiring teachers. Generally, there is only one school district in rural areas. They probably act more like monopsonists when setting wages when compared to their urban counterparts, which have competition for teachers from other districts and private schools.