Investment in Human Capital

In the previous chapter, we discussed some of the reasons why some people are paid more than others, including discrimination in the labor market and the role of unions. But even if we put these important considerations aside, other factors may lead to wage differences, such as how much education one has. Previously, we had treated labor as a homogeneous input to simplify our analysis. In this section, we look at labor that has been enriched by training or education and how it affects the productivity of firms.

investment in human capital Investments such as education and on-the-job training that improve the productivity of labor.

Is there a relationship between your earnings and your education? Let us first consider the role education and on-the-job-training (OJT) play in determining wage levels in labor markets. Workers, students, and firms all invest in themselves or their employees to increase productivity. This is called investment in human capital. Workers invest by accepting lower wages while they undertake apprenticeships. Students invest by paying for tuition and books, and by forgoing job opportunities, to learn new skills. Firms invest in their workers through OJT and in-house training programs that involve workers being paid to attend classes. These investments entail costs in the current period that are borne in the interest of raising future productivity.

Education and Earnings

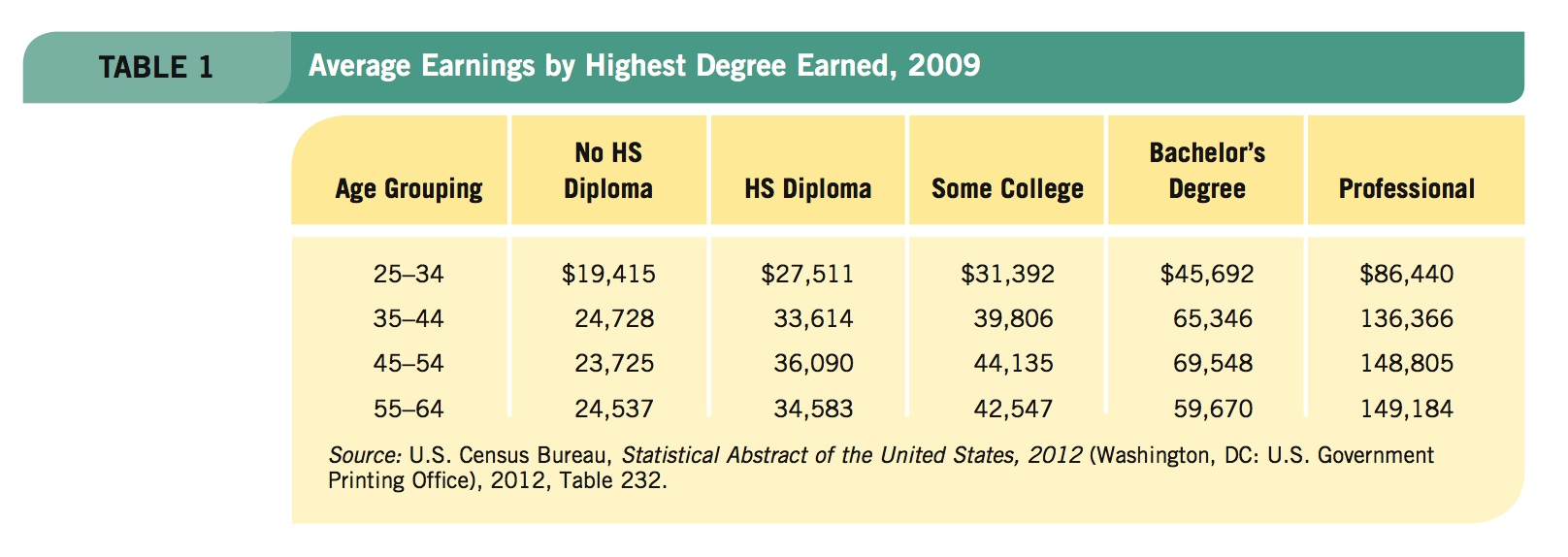

One of the surest ways to advance in the job world and increase your income is by investing in education. The old saying, “To get ahead, get an education,” still holds true. Table 1 shows the age/earnings profiles for all Americans between 25 and 64 for 2009. It provides strong evidence that education and earnings are related.

Average earnings for those without a high school diploma peaked at $24,728 a year, while those completing high school peaked at $36,090, a 45% increase. Getting a college degree bumped peak earnings up to $69,548, over a 180% rise. Going on to get a professional degree moved the peak all the way up to $149,184, over a 100% increase over a bachelor’s degree alone. These figures represent average earnings. It is easy to see that earnings in all age groups were much higher for those with higher levels of education.

Table 1 suggests that education is a good investment. But like any investment, future earnings must be balanced against the cost of obtaining that education. The costs of education must be borne today, but the earnings benefits do not arrive until later. Making optimal educational decisions therefore requires some tools to help evaluate investments in human capital markets.

Education as Investment

To keep our analysis simple, we will focus on the decision to attend college for four years. The basic approach outlined in this section will nonetheless apply to other investments in education or training.

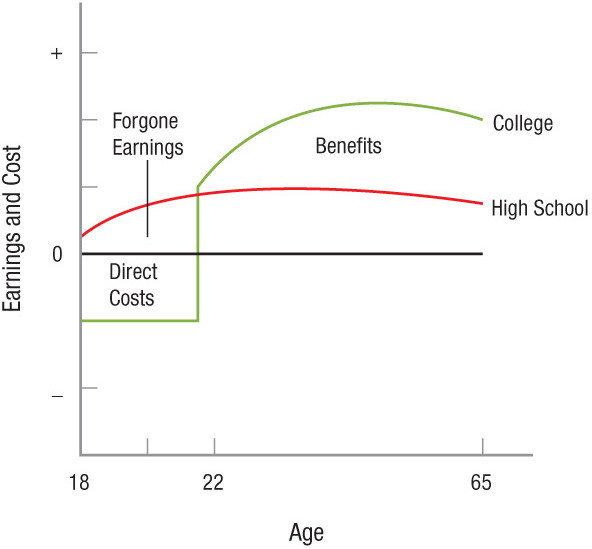

Figure 4 presents a stylized graph showing the benefits and costs of a college education. For simplicity, we will assume students go to college at age 18. If an individual chooses not to go to college, the high school earnings path applies: On leaving high school, the person enters the labor market immediately, and earnings begin rising along the path labeled “High School.” Note that the earnings are positive throughout the individual’s working life.

FIGURE 4

Benefits and Costs of a College Education If an individual chooses not to go to college at age 18, he or she enters the labor market on leaving high school, and earnings rise and fall along the path labeled “High School.” The college student incurs the direct costs of education, such as tuition and books, and the forgone earnings of not immediately entering the job market. The benefits of the college education show up as the difference in earnings from ages 22 to 65.

A college student immediately incurs costs in two forms. First, tuition, books, and other fees must be paid. These direct costs exclude living expenses, such as food and rent, because these must be paid whether one works or goes to college. Tuition varies substantially depending on whether one attends a private or public university.

Second, students give up earnings as they devote all their time to their studies (and to the occasional party). These costs can be substantial when compared to the direct costs of an education at a state-supported institution, because the average earnings for high school graduates range between $17,000 and $22,000 a year.

The benefits from a college degree show up as the difference in earnings from ages 22 to 65. If the return on a college degree is to be positive, this area must offset the direct costs of college and the forgone earnings. We must also keep in mind that a large part of the income high school and college graduates earn will not come until well into the future. For college graduates, this is especially important, because they will not see income for at least four years. How can we tell if this sacrifice is worth it? The fact that the median earnings of college graduates exceeded that of high school graduates by over 80% suggests a college education is worth it.1

An alternate way to decide which of the two career paths is best is by computing the rate of return on a college degree. If the annual return on a college education over the course of one’s working life is 10% a year, the earnings of the college graduate in middle age will exceed those of the high school graduate by enough to generate a 10% return. A lower return would mean that the difference in earnings is smaller, while a higher return suggests the difference in earnings is greater. An extensive study2 of rates of return to higher education in nearly 100 countries put the average return at nearly 20%. That is, college graduates around the world earn on average nearly 20% more per year over the course of their working lifetime than high school graduates, taking into consideration all of the costs of going to college.

Equilibrium Levels of Human Capital

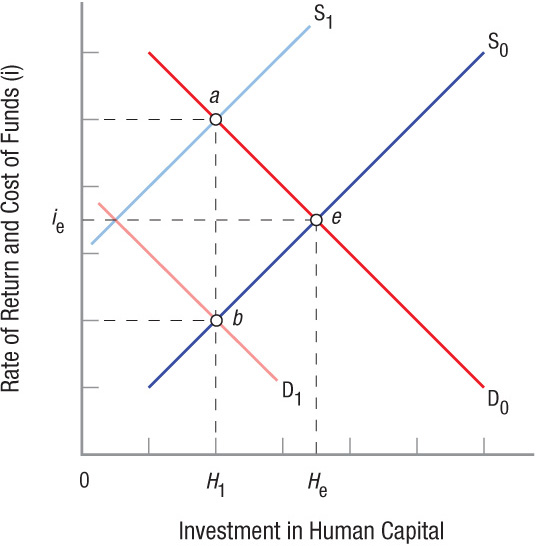

Each of us must decide how much to invest in ourselves. This decision, like so many in economics, ultimately depends on supply and demand, in this case, the supply of, and demand for, funds to be used for human capital investment. A hypothetical market for human capital is shown in Figure 5. In this scenario, “price” is the percentage rate of return on human capital investments and the interest cost of borrowing funds.

FIGURE 5

Equilibrium Levels of Investment in Human Capital This graph portrays a hypothetical market for human capital; the percentage rates of return and the interest costs of borrowing funds are shown on the vertical axis. With demand D0 and supply S0, equilibrium will be at point e. If the supply of funds is reduced (S1), interest rates and the cost of investment increase, resulting in less investment. Reduced demand for education (D1) similarly reduces human capital investment.

The demand for human capital investment slopes down and to the right, reflecting the diminishing returns of more education and that more time in school leaves you less time to earn back its costs. Students pursuing a Ph.D. or a medical degree are often into their thirties before they can begin paying back their student loans. As a result, they require higher salaries to bring their rates of return up above those of college-educated workers.

The supply of investable funds, meanwhile, is positively sloped, because students will use the lowest-cost funds first—mom and dad paying for college—then turn to government-subsidized funds, and finally use private market funds, if needed.

With demand (D0) and supply (S0), equilibrium in this market is at point e. Human capital investment is equal to He, with the rate of return equaling the interest rate (ie). Notice that reducing the supply of funds, or shifting the supply curve to S1, will increase interest rates and the cost of investment. This results in lower investments in education. Similarly, anything reducing the demand for funds, or shifting the demand curve to D1, will result in reduced human capital investment. Let us briefly consider some of the factors that might cause these curves to shift.

The most important factor determining the supply of investable funds for students consists of family resources. Students from well-off families can draw on a pool of inexpensive funds, but students from poorer families must scratch together funds that are often expensive. At the aggregate level, reductions in federally subsidized low-interest student loans will result in a shift in the supply curve to S1, meaning lower investments in human capital (H1). Conversely, the GI Bills enacted after World War II and the Vietnam War, along with recent tax policies that allow certain individuals to deduct a portion of their tuition payments from their taxes, have made a college education easier to afford. These policies have shifted the supply curve to the right and have increased college enrollments and the stock of human capital in America.

Another factor influencing human capital investment is discrimination. Assume D0 represents the demand for human capital investment for individuals facing no discrimination in the labor market. If these same people were to face a reduced wage in the market from wage discrimination, their demand for education would fall to D1, reffecting the reduced return on investment in human capital. A similar decline in demand would result if the choice of jobs is limited by occupational discrimination.

The demand for human capital is also influenced by an individual’s abilities and learning capacity: the more able the person, the larger the expected benefits of human capital investment.

Implications of Human Capital Theory

Individuals are more productive because of their investment in human capital, and thus they are capable of earning more during their working lives. Because younger people have longer earning horizons, they are more likely to invest in human capital and education. As workers get older and gain labor market experience and higher wages, their opportunity costs for attending college grow larger, while their potential post-college earning period shrinks. This explains why most students in college classrooms are young.

The greater the market earnings differential between high school and college graduates, the more people will attend college, because a higher earnings differential raises the return on college educations. Similarly, reductions in the cost of education lead to greater educational investment.

Further, the more an individual discounts the future—the more she or he values present earnings over future earnings—the less investment in human capital we would expect. People with high discount rates often are not willing to pursue doctoral or medical degrees because the time between the beginning of the training process and the point when earnings begin is simply too long.

Human Capital as Screening or Signaling

screening or signaling The use of higher education as a way to let employers know that the prospective employee is intelligent and trainable and potentially has the discipline to be a good employee.

Human capital theorists see investments in human capital as improving the productivity of individuals. This higher productivity then translates into higher wages. There is another view of why higher educational levels lead to higher wages: Higher education acts as a screening or signaling device for employers.

Economists who advocate this view concede that some education will undoubtedly lead to higher productivity. But these economists argue that higher education is largely an indicator to employers that the college graduate is trainable, has discipline, and is intelligent. In their view, the job market is one big competition in which entry-level workers compete for on-the-job training. As a result, earning a college degree does little more than give the college graduate a leg up in this competition.

Most economists, however, doubt the theory that screening is the only purpose served by higher education. If it were, the high costs of college education and the higher wages employers must pay college graduates would create tremendous incentives for workers and employers to develop an alternative, less expensive screening device.

On-the-Job Training

on-the-job training Training typically done by employers, ranging from suggestions at work to intensive workshops and seminars.

On-the-job training (OJT) is the investment by firms to increase the human capital of their workers, and can take many different forms. First, training can be as simple as receiving instructions from a supervisor on how to help customers, operate a machine, or retrieve items from inventory. Second, training can take place in a more formal setting away from the job, almost like a college course. Lastly, training can consist of a firm providing tuition reimbursement for college courses, professional certificates, or MBA degrees.

College internship programs are a good example of OJT that provide firms an extended look at potential employees while providing students with a look at several different firms and industries before graduating and entering the job market.

The Role of Educational Systems in Human Capital Accumulation

Countries use different strategies to promote human capital accumulation using their educational systems. For example, the educational system in the United States tends to emphasize a well-rounded curriculum by requiring most students to study subjects outside of their primary area of interest. Educational systems in Europe and Asia, however, tend to emphasize a more focused path of study, one in which students may select their area of study even before entering high school and take few courses outside of their major subject area. We can use anecdotal evidence to show how these differences translate into human capital outcomes.

For the United States, one can argue that emphasizing creativity and a diverse curriculum in the classroom has led to the development of world-renowned universities and research facilities, attracting students and researchers from around the world and leading to a huge boost in human capital. According to the annual Times Higher Education’s World University Rankings, the United States is home to 15 of the top 20 universities in the world, and 47 of the top 100 universities in the world.

However, a tradeoff exists in that emphasizing one area means less emphasis on others. For example, the U.S. primary and secondary educational systems have lagged behind much of the developed world in the subjects of math, science, and foreign language skills. According to the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment, in 2009 the United States ranked 25th out of thirty-four developed countries in math proficiency, while faring somewhat better (17th) in science. Finland and South Korea ranked at the top of most subject rankings.

What are other examples of policies aimed toward developing human capital through education? In Finland, which has one of the world’s top primary education systems, teachers are highly paid and teaching is considered a prestigious job requiring many years of postgraduate education. Interestingly, the amount of time children spend in school is less than in most developed countries, using the philosophy that “less is more” by emphasizing quality over quantity.

Saudi Arabia offers all of its citizens the opportunity to study at any college in the world (based on acceptance at a college on the approved list) that is fully paid by the Saudi king (The King Abdullah Scholarship Program). Although there are no strings attached to the offer, a large majority of students graduating from foreign universities under this program returned to Saudi Arabia to work, a huge boost to human capital.

Regardless of how countries educate their citizens, investments in human capital lead to economic growth, making such investments among the most valuable in terms of the return on money spent.

Today, spending on OJT exceeds $100 billion a year, including training costs and the wages paid to employees during training. The costs of OJT are usually borne by employers, but workers may bear some of the costs through reduced wages throughout the training period. Firms benefit from OJT by gaining more productive workers, and workers gain by becoming more versatile, and thus more competitive, in labor markets. Because all OJT entails present costs meant to yield future benefits, firms choose to provide OJT if the returns from this investment compare favorably to other investment alternatives.

Investments in human capital go a long way toward explaining why people are paid different wages. Education and earnings are closely related. Human capital theorists believe that this is because education and productivity are closely related. For this reason, firms are willing to pay higher wages to individuals with greater amounts of human capital. For industries that require advanced skills, such as in computer programming, aerospace, and biotechnology (just to name a few), human capital is difficult if not impossible to replace with ordinary labor. Therefore, human capital is considered a capital input in the factors of production.

INVESTMENT IN HUMAN CAPITAL

- Investment in human capital includes all investments in human beings such as education and on-the-job training.

- There is a positive relationship between education and earnings.

- The rate of return to education is computed by comparing the streams of income from two different levels of education.

- The greater the wage differential between two levels of education, the more people will pursue that next level of education.

- Higher education may just be a screening or signaling device telling potential employers that this individual is trainable, has discipline, and is intelligent.

- Firms are willing to provide on-the-job training when the future returns to human capital investment in terms of increased productivity to the firm exceed the costs of that training.

QUESTION: If the United States decided, as part of an immigration reform package, to restrict immigration only to those with college degrees, and thus decided to allow only 500,000 foreigners a year to enter, what would happen to the rate of return on college education? Alternatively, if, as part of a reform package, 500,000 low-skilled workers were permitted to enter the United States, what would happen to the rate of return on college education?

Letting in a large number of college-educated immigrants would drive the rate of return on college down as wages of college graduates would not grow very rapidly. The opposite would occur when unskilled immigrants enter, holding down the wages of those without college educations, leading to a growing gap between those with college degrees, increasing the rate of return to a college degree.