Externalities

Actions by individuals and firms affect not only those involved, but also can create side effects for others in ways that can be either beneficial or costly. For example, suppose you share an apartment with a neat and organized person. Because your roommate always keeps the apartment clean and uncluttered, you reap the benefits of not having dishes piling up in the sink or potato chip crumbs all over the sofa. Clearly, you benefit from this situation. On the other hand, suppose the occupants of the apartment next door are members of an aspiring heavy metal band. They blast loud music all day, and occasionally have a jam session—and you’re forced to hear everything they play. Unless you enjoy that music yourself, your neighbors’ actions become a cost for you.

externalities The impact on third parties of some transaction between others in which the third parties are not involved. An external cost (or negative externality) harms the third parties, whereas external benefits (positive externalities) result in gains to them.

Externalities, often called spillovers, arise when actions or market transactions by an individual or a firm cause some other party not involved in the activity or transaction to benefit or be harmed. If the activity imposes costs on others, it is called a negative externality or an external cost. If the activity creates benefits to others, this is a positive externality or an external benefit. Negative externalities include air and water pollution, littering, and chemical runoff that affect fish stocks. Examples of activities that generate positive externalities include getting a flu shot, acquiring more education, landscaping, and maintaining beehives next to apple orchards.

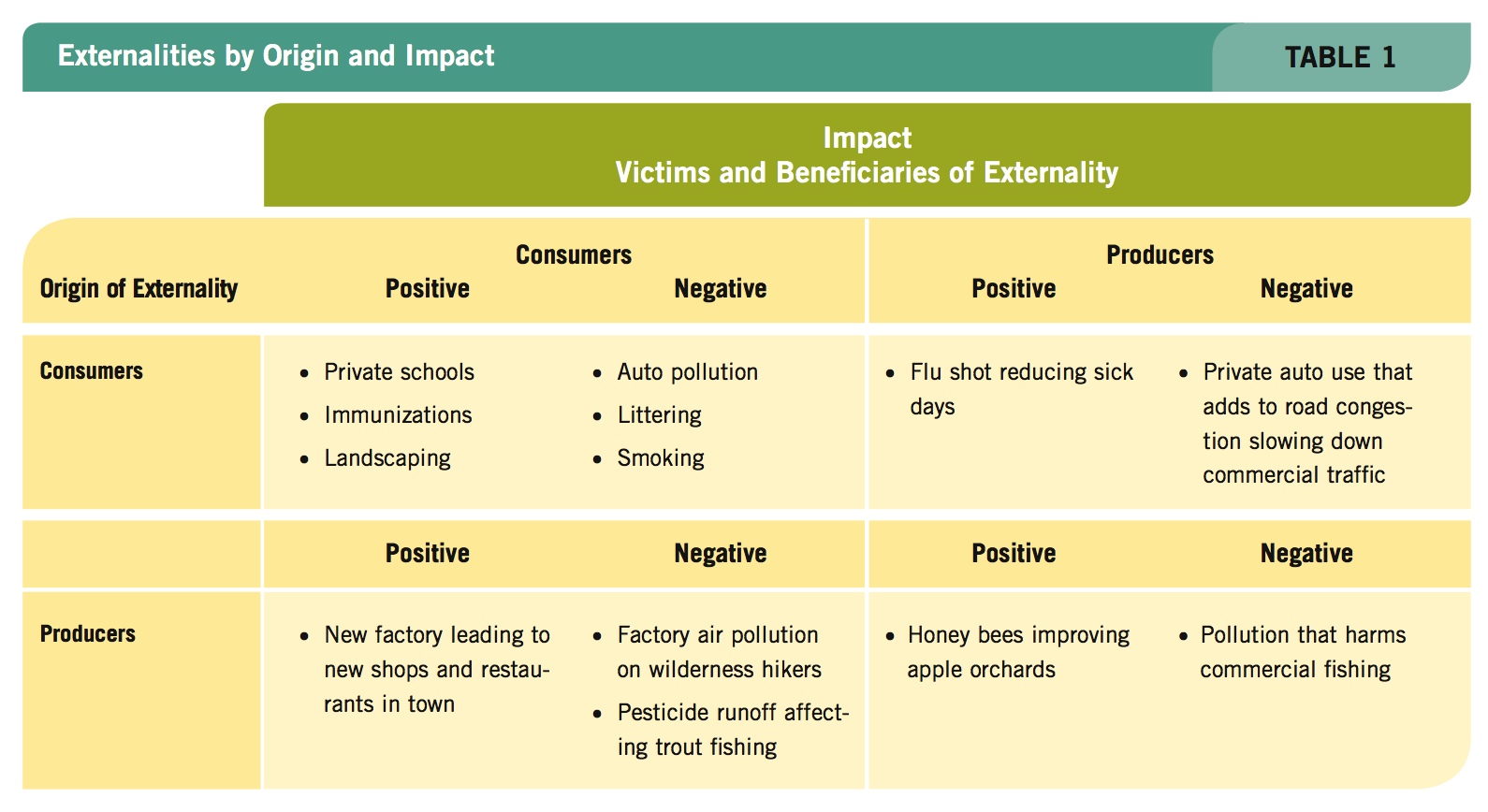

Both producers and consumers can create externalities and can feel the effects of them. The matrix in Table 1 identifies the origin and impact of some common external effects.

Negative Externalities

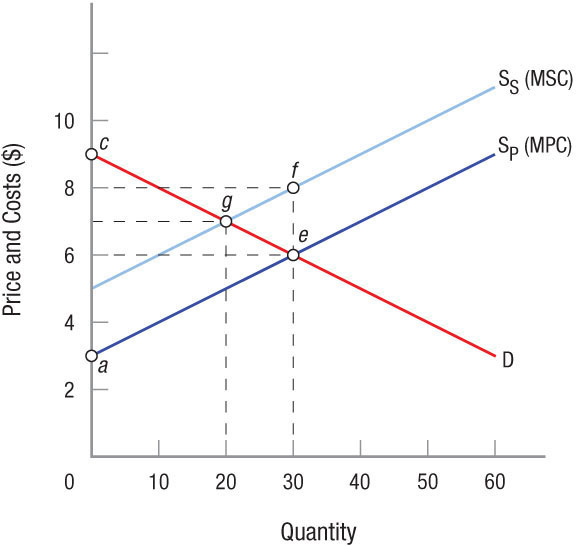

When a market transaction harms people not involved in the transaction, negative externalities exist. Pollution of all sorts is the classic example. Firms and consumers rarely consider the impact their production or consumption will have on others. For simplicity, we focus on the pollution caused by production. Figure 1 shows a typical market.

FIGURE 1

The Negative Externality Case Supply curve SP represents the manufacturer’s supply when only its private costs are considered, ignoring the external costs imposed on others through pollution. Market equilibrium is 30 units sold at $6 each (point e). If each unit of production results in $2 in pollution costs, then supply curve SS represents the marginal social costs (MSC) to manufacture the product. Socially optimal output is 20 units sold at $7 each (point g).

Supply curve SP represents the manufacturer’s marginal private cost (MPC) of production. This supply curve ignores the external costs imposed on others from the pollution generated during production. These external costs might include toxic wastes dumped into lakes or streams, smokestack soot, or the clear-cutting associated with timber harvests. Ignoring these costs, market equilibrium is at point e, at which the product is priced at $6 and 30 units are sold.

Recall from Chapter 4 that one way to measure the well-being of consumers and producers in a market is to measure the consumer surplus and producer surplus. Consumer surplus is the difference between what consumers are willing to pay for a good (shown by the demand curve) and the market price (equal to $6 in Figure 1). Therefore, consumer surplus is equal to $45 [(($9 − $6) × 30) / 2]. Producer surplus is the difference between the market price and the minimum amount at which sellers are willing to sell a product (shown by the supply curve), and is equal to $45 as well [(($6 − $3) × 30) / 2]. Summing up consumer surplus and producer surplus equals $90, which is shown as area ace in the figure.

Now let’s assume that for every unit of the product produced, pollution costs (or effluent) equal to $2 is generated. Thus, at an output level of 30 units (point e), $60 in pollution costs (or negative externalities) are generated. Subtracting this $60 in pollution from total consumer and producer surplus results in $30 of real social benefit from this output.

This means that the true marginal cost of producing the product, including pollution costs, is equal to supply curve SS, representing the marginal social cost (MSC) of production. This new supply curve incorporates both the private and social costs of production, thus shifting supply upward by an amount equal to ef, or $2. Equilibrium moves to point g, at which 20 units of the product are sold at $7. This is the socially optimal production for this product given the pollution it creates.

So why is it better for society than when 30 units were produced? First, notice that when output is 20, the cost of the last unit produced—including the cost of pollution—is $7 (point g). This is just equal to the value society attributes to the product. Hence, consumers get just what they want when all costs are considered. Second, notice that consumer and producer surplus at an output of 20 units is $40 [(($9 − $5) × 20) / 2]. More important, it is now higher than the $30 of consumer and producer surplus minus the pollution costs when output was 30 units (point e).

Each unit of output produced beyond 20 costs more—taking both private and social costs into account—than its value to consumers.

Imagine a situation in which external costs exceed the consumer and producer surplus from consuming the good. Such a situation might arise when an extremely toxic substance is a by-product of production. Society is better off not permitting production of this good.

What has this analysis shown? First, when negative externalities are present, an unregulated market will produce too much of a good at too low a price. Second, optimal pollution levels are not zero, except in the case just mentioned of extremely toxic agents. In Figure 1, the socially optimal production is 20 units with total pollution costs of $40. Pollution reduction as a good has no price. Even so, we can infer a price, known as a shadow price, equal to the marginal damages—$2 per unit in this case. As we will see later, prices for the “right to pollute” will provide us with better approximations of the costs of pollution.

The Coase Theorem

Ronald Coase was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics for his seminal paper, “The Problem of Social Cost.” Coase has written few articles—less than a dozen—but, as economist Robert Cooter noted, although “most economists maximize the amount they write, Coase maximized the amount others wrote about his work.”1 Indeed, Coase’s paper on social cost is one of the most cited works in economics.

Coase theorem If transaction costs are minimal (near zero), a bargain struck between beneficiaries and victims of externalities will be efficient from a resource allocation perspective. As a result, the socially optimal level of production will be reached.

Reducing output to the optimal level results in gains to “victims” because pollution is reduced. The reduction in output, however, causes losses to producers. The presence of losses and gains to two distinct parties, Coase argued, introduces the possibility of bargaining, provided that the parties are awarded the property rights necessary for negotiation.

The Coase theorem states that if transaction costs are minimal (near zero), the resulting bargain or allocation of resources will be efficient—output will decline to the optimal level—regardless of the initial allocation of property rights. The socially optimal level of production will be reached, that is, no matter whether polluters are given the right to pollute or victims are given the right to be free of pollution.

Even so, the distribution of benefits or income will be different in these two cases. If victims, for example, are assigned the property rights, their income will grow, but if polluters are assigned these rights, the income of victims will decline.

As Coase noted, for these efficient results to be achieved, transaction costs must approach zero. This means it must be possible for polluters and victims to determine their collective interests accurately, then negotiate and enforce an agreement. In many situations, however, this is simply not feasible. In cases involving air pollution, for instance, polluters and victims are so widely dispersed that negotiating is impracticable. In other cases, individuals may be both victims and polluters, making it difficult for an agreement to be reached and enforced.

Another problem associated with assigning rights to one party or another might be called environmental mugging. Polluters might at first threaten to pollute more than they anticipate, for instance, to increase their bargaining leverage and, ultimately, their income. Victims, in like manner, might assert exaggerated environmental concerns, again to bid up their compensation. Alternatively, if negotiations should prove to be unfruitful, polluters might start lobbying for legal relief, thus devoting their money to rent-seeking behaviors rather than buying pollution-abatement equipment.

NOBEL PRIZE RONALD COASE

University of Chicago professor Ronald Coase won the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 1991 for “his discovery and clarification of the significance of transaction costs and property rights” in the institutional structure and functioning of the economy. According to his analysis, traditional microeconomic theory was incomplete because it neglected the costs of executing contracts and managing firms. To Coase, these “transaction costs” were the principal reason that firms existed. Economic actors found it cost efficient to create a more complex organization to minimize transaction costs.

Coase also analyzed the economy in terms of the rights to use goods and factors (inputs) of production rather than the actual goods and factors themselves. These “property rights” could be defined in different ways according to contracts and rules within organizations. Coase introduced the concept of property rights as an important element of economic analysis.

Born in 1910 in Willesden, a suburb of London, Coase attended the London School of Economics (LSE), where he earned a Bachelor of Commerce degree in 1932, and returned 15 years later and earned a Doctor of Science degree in economics in 1951. Becoming disillusioned with the future of British socialism and taking “a liking for life in America,” he migrated to the United States in 1951 and taught at the University of Buffalo. Coase’s 1960 article, “The Problem of Social Cost,” questioned whether governments could efficiently allocate resources for social purposes through taxes and subsidies. He argued that arbitrarily assigning property rights and using markets to reach a solution was usually better than costly government regulation. This was instantly controversial and led to a lengthy exchange of papers in economics journals. In 1964, Coase joined the faculty at the University of Chicago and became editor of the Journal of Law and Economics. The journal was an important catalyst in developing the economic interpretation of legal issues.

Although the private negotiations Coase proposed have their limitations, his insights proved to be a turning point in environmental policy. Coase challenged the prevailing practice of assuming that victims had a right to be pollution-free. His analysis stressed that it does not matter who the rights are assigned to (the polluter or the pollution-victim, for example). No matter how property rights were assigned, if information was good and transaction costs were low, efficiency would result. Given the costs of pollution, affected parties have an incentive to work out efficient agreements.

This idea was so radical when Coase published “The Problem of Social Cost” in 1960 that another Nobel Prize winner, George Stigler, wondered “how so fine an economist could make such an obvious mistake.” Coase was later invited to the University of Chicago to discuss his ideas; Stigler described what transpired2:

We strongly objected to this heresy. Milton Friedman did most of the talking, as usual. He also did much of the thinking, as usual. In the course of two hours of argument the vote went from twenty against and one for Coase to twenty-one for Coase. What an exhilarating event! I lamented afterward that we had not had the clairvoyance to tape it.

The Coase theorem has changed the way economists look at many issues, not just environmental problems. In cases in which the costs of negotiation are negligible and the number of parties involved is small, economists and jurists have begun to look more closely at legal rules assigning liability.

Positive Externalities

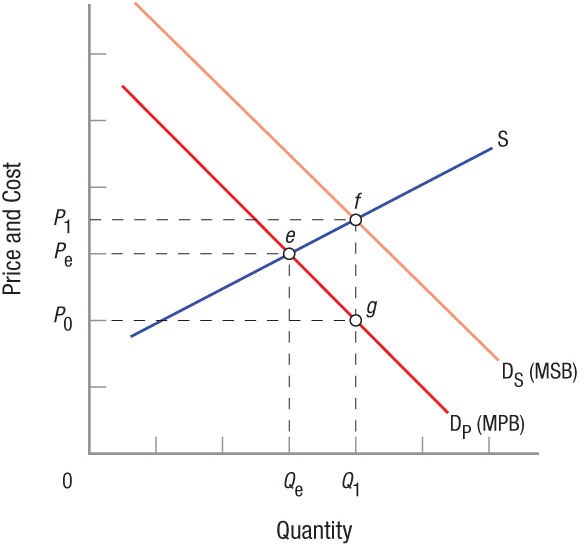

When private market transactions generate benefits for others, a situation opposite to that just described results. Figure 2 illustrates a positive externality. Market supply curve S and private demand curve DP (equal to the marginal private benefit, MPB, of consumption) represent the market for college education. Equilibrium is at point e, with Qe students enrolling. Society would clearly benefit, however, if more people received a college education: Tax revenues would rise, crime rates would fall, and a better-informed electorate might produce a better-operating democracy.

FIGURE 2

The Positive Externality Case Market supply curve S and private demand curve DP represent the market for college education. Equilibrium is at point e, and the number of students enrolled is Qe. Society would benefit, however, if more people would go to college. Demand curve DS represents the marginal social benefit (MSB), which includes the private demand for college education plus the external benefits that flow from it. Socially optimal enrollment would be Q1 (point f).

Taking these considerations into account, social demand curve DS is the private demand for college education plus the external benefits that flow from it. Socially optimal enrollment would be Q1 (point f). How can society tweak the market so that more students will attend college? Students will demand Q1 levels of enrollment only if its price is P0 (point g). The public must therefore subsidize college education by fg to draw its price down to P0.

The U.S. government recognizes that college education benefits society at large when it provides low-interest student loans, grants, and scholarships to students attending colleges and universities.

Limitations

Some caveats about our analysis of externalities need to be noted. First, producer and consumer surpluses are good measures of society’s welfare if all incomes are weighted equally or the distribution of income is optimal. When income is unequally distributed, gross unfairness created throughout society swamps any improvements from efficiency. Thus, measures of efficiency such as consumer and producer surplus can become unconvincing for public policy. Because no one can agree on the correct distribution of income, economists generally ignore this question and focus on efficiency.

Second, the discussion has focused on the pollution that arises from production, not consumption. The results applied to congestion and littering, however, would be substantially the same.

Third, the examples presented here have assumed, moreover, that pollution has no cumulative effects. And, indeed, smaller amounts of pollution effluence may just flow into the ocean, for instance, with no lasting effects. But the same will not hold true for sustained higher pollution levels.

Fourth, for convenience, we have assumed that we can assign specific amounts to the damages resulting from pollution. In practice, this is not always easy to do.

Fifth, we have assumed that pollution can be reduced only by reducing output, but in real markets, there are other ways to reduce pollution.

Despite these limitations, the analysis presented here helps us focus our attention on ways of reducing the harm done to society by negative externalities.

market failure When markets fail to provide the socially optimal level of output, and will provide output at too high or low a price.

In summary, the presence of externalities leads to overuse of resources and environmental degradation, causing a market failure to occur, when markets fail to provide the socially optimal level of goods and services. Another type of market failure occurs when resources are not privately owned, which we discuss in the next section.

EXTERNALITIES

- Externalities arise when the production of one good generates benefits (positive externalities) or costs (negative externalities) for others not involved in the transaction.

- When negative externalities exist, overproduction is the result. When positive externalities are generated, underproduction of the good is the norm.

- The Coase theorem states that if transaction costs are minimal (near zero), no matter which party is provided the property rights to pollution (polluter or victim), the resulting bargain will result in the socially optimal level of pollution.

QUESTION: Compact fluorescent light (CFL) bulbs have grown in popularity as their quality improves and prices fall. But not all consumers are convinced of the benefits of CFL bulbs. Proponents point to the tremendous energy savings, because CFL bulbs require only about 20% of the energy used by incandescent light bulbs, and they last much longer as well. Critics point to the potential dangers of mercury contained in CFL bulbs, along with a less desirable light color emitted by CFL bulbs. In addition to these private benefits and costs, what are some external benefits and external costs that are created by the use of CFL bulbs?

CFL bulbs create external benefits by reducing the overall use of energy, thus keeping energy prices lower for all consumers. The longer life of CFL bulbs also reduces waste and pollution. CFL bulbs can also create external costs. For example, careless disposal of CFL bulbs may allow mercury, a harmful toxin, to leak into landfills and into the environment, potentially harming all persons.