Public Goods

We saw in the previous section that externalities can lead to markets not providing the socially efficient amount of a good at the optimal price. Either too much or too little of the good is produced, or it is offered at too high or too low a price, leading to a market failure. The presence of externalities is one cause of market failure. This section looks at two other causes of market failure that arise when no individual or firm is able to claim ownership of a product. These goods and services are called public goods and common property resources.

What Are Public Goods?

public goods Goods in which one person’s consumption does not diminish the benefit to others from consuming the good (i.e., nonrivalry), and once provided, no one person can be excluded from consuming (i.e., nonexclusion).

nonrivalry The consumption of a good or service by one person does not reduce the utility of that good or service to others.

nonexcludability Once a good or service is provided, it is not possible to exclude others from enjoying that good or service.

Pure public goods are nonrival in consumption, and exhibit nonexcludability. Nonrivalry means that the consumption of a good or service by one person does not reduce the utility of that good or service to others. Nonexcludability means that it is not possible to exclude some consumers from using the good or service once it has been provided.

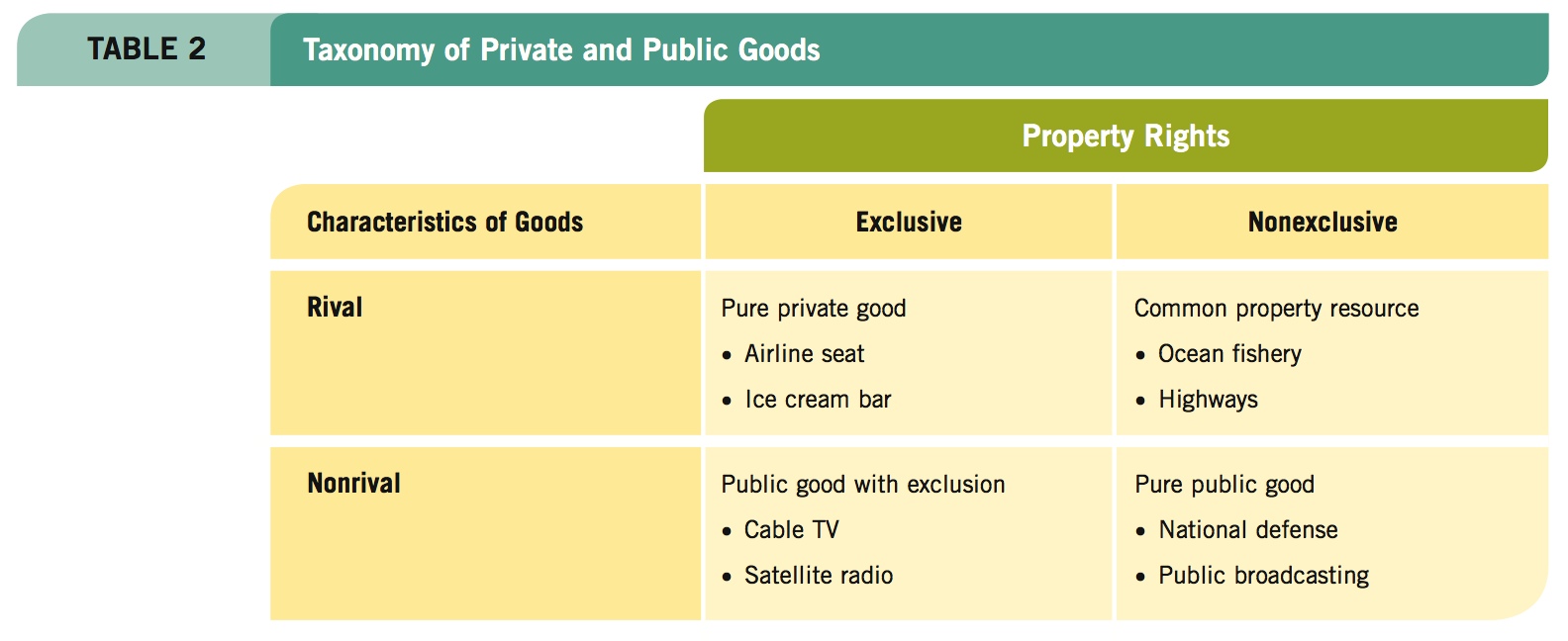

By way of contrast, a can of Coke is a rival product. When you drink a can of Coke, no one else can drink that same can. Airline flights exhibit excludability—one must either buy a ticket or obtain an award ticket to board the plane, even if empty seats are available. But consider a lighthouse. Once it is built and in operation, all ships can see the lighthouse and use the light to avoid obstacles. One captain’s use of the lighthouse does not prevent another from using it, nor can a ship realistically be excluded from using the lighthouse’s services. Hence, the lighthouse is a public good. Other examples of public goods include national defense, accumulated knowledge, standards such as a national currency, protection of property rights, vaccinations, mosquito spraying, and clean air. Table 2 provides a taxonomy of private and public goods.

free rider The ability of an individual to avoid paying for a public good because he or she cannot be excluded from enjoying the good once provided.

Consumers cannot be excluded from a public good once it is provided, therefore they have little incentive to pay for the good in question. Instead, most will essentially be free riders. Think of the lighthouse again. If you have a ship and cannot be excluded from the benefits the lighthouse provides, why should you contribute anything to the lighthouse’s upkeep? But if everyone took this position, there would be no support for the lighthouse, and it would go into decline. With free riders, private producers cannot hope to sell many units of a good, and thus they have no incentive to produce it. Private markets will therefore fail to provide public goods, even if the goods are things everyone would like to see produced. This is why the government or special interest groups must get involved in the provision of products and services that have significant public good characteristics.

344

The Demand for Public Goods

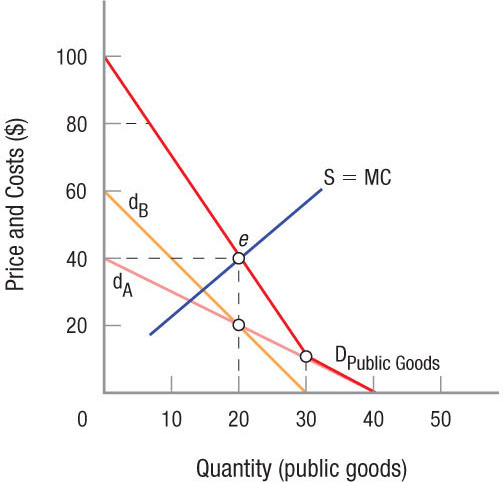

Assessing the public’s demand for public goods is clearly different from that of private goods where we found market demand by horizontally summing private demands. But the fact that once a public good is supplied, no one can be excluded from consuming it, and one person’s consumption does not affect another’s, plays a crucial role. Figure 3 provides a solution to finding the demand for public goods.

Figure 3 shows demand for a public good by two different consumers. Individual A wants none when the price is $40 and is willing and able to buy 40 units when the price approaches zero. Individual B wants none when the price is $60 and only is willing to buy 30 units when the price nears zero. Because each consumer can consume any given amount of a public good at the same time, the total demand for a public good is found by summing the individual demands vertically. To see why, consider when both individuals demand 20 units. This is the point at which the two demand curves cross, and both are willing to pay $20 for 20 units. Thus, total demand for 20 units is $40. The total demand for the public good in Figure 3 is shown by the heavy line labeled DPublic Goods and is the vertical summation of individual demands.

345

Notice how this differs from our discussion of market demand curves for private goods. For private goods, others could be excluded from consuming any good we bought, therefore demands were horizontally summed. In contrast, with public goods, exclusion is not possible, therefore both individuals can consume the good simultaneously, and market demand is found by summing vertically. Market demand for public goods is really a willingness-to-pay curve, because the government will have to provide the good and levy taxes to pay the cost.

Optimal Provision of Public Goods

Providing the optimal amount of public goods is easy in theory and is illustrated in Figure 3. The supply of public goods is equal to the marginal cost curve (S = MC) shown in the figure. Just like the competitive market equilibrium we covered earlier, optimal allocation is where MC = P, and in this instance, it is 20 units of the good at a total price of $40 (point e). In this example, the taxes are split equally between individuals A and B. Determining how much tax each person should (or would be willing to) pay is hampered by the fact that once the public good is provided, no one can be excluded, therefore individuals will be unwilling to reveal their true preferences for the good because it might mean that they would have to pay a higher tax.

In reality, providing public goods such as national defense involves the political process. This means that politicians, bureaucrats, special interest groups, and many others generate the decisions on how much of any particular public good to provide. Since the demand for a public good represents the benefits to society and the supply curve represents society’s costs, equating marginal benefits and marginal costs yields the optimal amount. But estimating the demand (benefits) from public goods and their costs can be a complex process. Most people desire the benefits of a strong military, but few enjoy paying the taxes required to pay for the cost. Because people cannot be excluded from the good, once provided, they have little incentive to reveal their true preferences, making this type of market failure difficult to overcome.

Common Property Resources

tragedy of the commons Resources that are owned by the community at large (e.g., parks, ocean fish, and the atmosphere) and therefore tend to be overexploited because individuals have little incentive to use them in a sustainable fashion.

Commonly held resources are subject to nonexclusion but are rival in consumption. The market failure associated with such resources is often referred to as “the tragedy of the commons.”3 The tragedy here is the tendency for commonly held resources to be overused and overexploited. Because the resource is held in common, individuals race to “get theirs” before others can grab it all.

One example of commonly held resources giving rise to problems involves oil fields. Oil reservoirs often span the surface property of many landowners. Because oil reservoirs are regarded as common property, each surface owner has an incentive to drill as many wells as possible and to pump out oil as rapidly as possible. Having too many wells pumping too quickly, however, reduces the oil field’s water and gas pressure, thus reducing the total recoverable oil from the reservoir. Each owner’s decision to drill a well therefore imposes an external cost on the other owners of land over the reservoir. At one point, this problem grew so severe that it resulted in passage of the 1935 Connally “Hot Oil” Act. This act restricted drilling, regulated the number and location of oil wells, and capped pumping rates.4

346

Tragedy of the Commons: The Perfect Fish

Ocean fisheries are a good example of the problem of common property resources. Fish in the ocean were once in excess supply; there was no need to restrict the use of this resource. As global demand for fish rose, improved fishing technologies allowed fishing boats to increase their hauls. Because many of the world’s fisheries are still unregulated, one species after another has been fished out in a clearly unsustainable situation.

The Patagonian toothfish, as it is known, lives up to 50 years and can weigh over 200 pounds. This big, ugly, gray-black fish lives in the cold deep waters of the Southern Ocean near Antarctica, and in the 1990s, it became the signature dish of top restaurants in the United States, Japan, and Europe. It became so popular that during the mid-1990s, the annual catch was estimated at 100,000 metric tons.

How did such an ugly fish with such an unappetizing name become so popular? In the late 1970s, Lee Lantz, a Los Angeles fish merchant, visited the docks in Valparaiso, Chile, and spotted a toothfish. He bought a sample and cooked it, but the oily flesh had little taste. Most fish have bladders that they inflate to adjust their buoyancy, reducing the energy it takes to move up and down in the water. Toothfish do not have bladders, but use oil (lighter than water) secreted to create buoyancy. Also, Patagonian toothfish are predators, waiting in ambush for prey. Thus, they do not need a lot of blood rushing through their system. As a result, toothfish meat is oily and white like cod. It is this oiliness—along with the fact that it absorbed any spice—that made the toothfish (now known as Chilean sea bass) a hit with restaurants.

As the reputation of the toothfish spread, so did the take in the ocean. Because this fish is found in the Southern Ocean where it is cold and where few venture, it was highly susceptible to poaching. A full hold of toothfish could fetch $1 million wholesale!

Soon it became clear to many that the species was being seriously overharvested, and chefs began to notice that the filets were getting smaller. The tragedy of the commons was playing out again. Soon chefs from the best restaurants organized a boycott campaign called “Take a Pass on Chilean Sea Bass.” Today, limits are set on the catch, and Chilean sea bass is coming back from the brink of extinction. But as G. Bruce Knecht reported in his book Hooked, keeping pirates from poaching the toothfish is a dangerous job for the Australian Customs patrols. The toothfish’s problem is that it is the perfect fish.

Source: G. Bruce Knecht, Hooked: Pirates, Poaching, and the Perfect Fish (Emmaus, PA: Rodale), 2006.

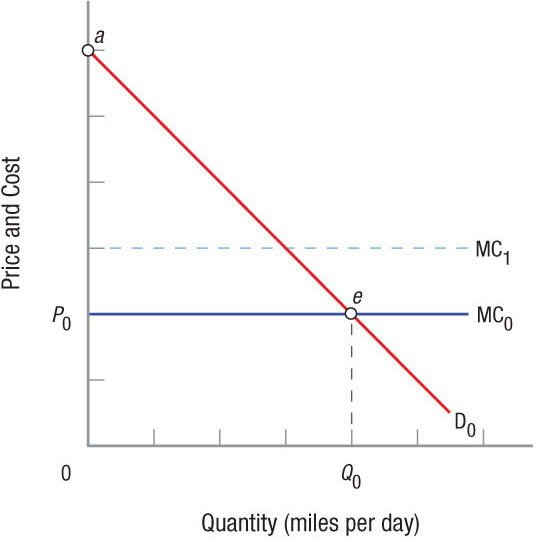

Road congestion is another illustration of the tragedy of the commons. Figure 4 shows a market for usage of a road that is fully used and is right at the tipping point before becoming congested. In Figure 4, demand for driving on this road is D0, and the marginal cost to use the road—gas, time, and auto expenses—is initially MC0. Equilibrium is at point e, with Q0 miles per day driven. Consumer surplus is area P0ae for the typical driver.

347

Now assume that a new driver begins using the road. This increases the marginal costs of driving to MC1 for everyone, because the tipping point has been passed, and the road is now congested. Consumer surplus shrinks because of overuse of the commons. Note that the new driver did not take these external costs into consideration; the driver assumed that the marginal cost would be equal to MC0, not MC1.

Possible solutions to common property resource problems can involve establishing private property rights, using government policy to restrict access to the resource, or informal organizations that restrict each user’s benefits from the resource. Reduced congestion, for example, could be achieved by raising the tax on gasoline, subsidizing bus or rapid transit travel, or privatizing roads and allowing the owners to charge tolls.

The optimal provision of public goods, whether pure public goods or common property resources with significant public goods characteristics, is a significant challenge faced by society. Individuals tend to act in their self-interest when using public goods without contributing to their provision (free-riding) or overusing a resource without considering the impact of such use on others. An example of a public good that has risen to the forefront of policy debate is the environment, which we all share. We turn to environmental policy next.

PUBLIC GOODS

- Pure public goods are nonrival in consumption, and once the good is provided, no one can be excluded from using it.

- The demand for public goods is found by vertically summing individual demand curves.

- Optimal provision of public goods is found where the marginal benefit of public goods (demand) is equal to the marginal cost of provision.

- Determining the optimal provision of public goods is easy in theory, but difficult in practice.

- Common property resources have the characteristics of nonexcludability but are rival. This typically leads to overuse and overexploitation.

QUESTION: On most college campuses, the use of the recreation center is open to all registered students without an additional fee. The cost of running the recreation center typically is paid for by an activity fee paid by all students, regardless of whether they use the facilities or not. In what ways does your campus recreation center resemble a public good? In what ways does it not?

If the recreation center on campus allows all students to use it without an additional fee, it resembles some of the characteristics of a public good. Although it can exclude nonstudents from the facility, it is open to all students. Therefore, it is partially nonexcludable. However, if too many students use it, it can become crowded, resembling more of a common property resource.