Competition and Market Structure for Network Goods

The network goods industry provides opportunities for firms to gain substantial market power. Such opportunities often lead to intense competition. A recent example of competition in network goods was the market for high-speed home Internet service between DSL providers (such as AT&T) and cable Internet providers (such as Comcast). With a majority of U.S. households having switched from dial-up Internet services to high-speed providers in the past decade, the race to become the dominant provider was critical to AT&T and Comcast.

AT&T focused on bundling strategies with their U-verse program that incorporates home phone, digital television, and high-speed Internet for one price. Comcast, in addition to their Xfinity program that bundles television, home phone, and Internet, invested heavily in television advertising featuring the Slowskys, a turtle couple that had an aversion to anything fast and was used as a metaphor for DSL-service speed.

This section describes some of the common strategies used to protect network goods from entering a vicious cycle or to increase the likelihood of entering a virtuous cycle. Undoubtedly, as a consumer, you encounter many of these marketing strategies when making decisions about which network goods to purchase. The goal of firms using these strategies is to attract you to their product and to keep you as a customer for a long time.

Competition and Pricing Strategies

Network goods are characterized as having high fixed costs with low marginal costs. Further, network effects can cause some firms to flourish while causing others to fail, even when little or no quality differences exist between the firms’ products. The determinant of market success is not always dependent on the quality of the good, but rather on competitive strategies to capture market share. Low marginal costs means it does not cost much to serve customers once they are committed to a product. Therefore, firms spend significant sums of money to gain new customers and use various strategies to keep existing customers. These strategies include teaser strategies, lock-in strategies, and market segmentation (such as product differentiation and price discrimination).

teaser strategies Attractive up-front deals used as an incentive to entice new customers into a network.

switching cost A cost imposed on consumers when they change products or subscribe to a new network.

Capturing New Customers Using Teaser Strategies Teaser strategies are used by firms to gain new customers by offering various sign-up incentives and/or low prices for a short introductory period. Examples of teaser deals include wireless companies offering a free or highly discounted phone when purchasing a two-year wireless plan, cable companies offering six months of free cable or Internet service, banks offering 0% finance charges for a limited time when opening a new credit card account, online music companies offering new customers fifty free music downloads, and software companies allowing new users to sample their products with a 30-day free trial.

Why do companies offer such great deals to new customers? Unlike decisions for nonnetwork goods, such as which brand of cereal to buy—a decision that is relatively easy to switch back and forth—purchasing a network good typically requires a long-term commitment. This can be due to a legal commitment, such as a one- or two-year contract, or it can be due to nonmonetary costs of switching from one product to another.

lock-in strategies Techniques used by firms to raise the switching costs for its customers, making it less attractive to leave the network.

Have you ever had to switch from a software program that you have used for many years? Once you learn how to use a particular software program or once you are accustomed to a certain email program, it can be a hassle to switch to another. These switching costs, which include monetary and nonmonetary costs of switching from one good to another, often are substantial for network goods. Therefore, to provide incentives for consumers to incur these costs to switch, firms must offer attractive up-front deals.

In addition to offering teaser deals to entice new customers, firms also employ strategies to keep existing customers from leaving. Lock-in strategies occur after a customer adopts a product, and typically involve the firm engaging in strategies that raise the switching costs of consumers, thereby increasing the likelihood of retaining the customer.

Switching costs include the hassle of learning a new format and its features, dealing with the loss of other features one has become accustomed to, and so forth. In some cases, switching costs may be minimal or offset by benefits; for example, the excitement of purchasing the latest smartphone or computer may outweigh the switching costs of learning how to use it. But consumers generally do not like changing network goods once they are accustomed to one brand.

Common examples of lock-in strategies include the offering of loyalty programs, which reward consumers the more they use or the longer they stay with a company’s products. Lock-in strategies also include preventing certain features from being transferred to another product, such as a phone’s contact list or saved text messages.

market segmentation A strategy of making a single good in different versions to target different consumer markets with varying prices.

In Chapters 9 and 10, we saw how market power can reduce the elasticity of demand for a firm’s product and increase potential profits of monopolies and monopolistically competitive firms. We draw from those analyses by studying how market segmentation strategies can be used to increase market share and profits in the market for network goods. Market segmentation is achieved when firms can differentiate their products in a way that allows similar goods to be priced differently to different groups of consumers. In other words, it allows firms to price discriminate, which increases producer surplus (as discussed in Chapter 9).

Do Exclusive Marketing Deals Lock In Customers?

Competition among telecommunication providers has flourished since 1984, when the U.S. government forced AT&T, which at the time was the monopoly provider of about 80% of all telephone services, to break apart into seven regional companies and a long-distance company, and to allow competition in long-distance service. Almost immediately, long-distance companies MCI and Sprint began offering long-distance services equal to AT&T’s services, and competing vigorously against AT&T for customers. In the 1990s, competition among these three carriers involved advertising in the form of nearly endless sales calls to people’s homes, often during dinnertime, which eventually led to the creation of “Do Not Call” registries.

Today, competition among wireless carriers is as intense as competition among long-distance carriers was in the 1990s. But with limitations on advertising via sales calls, companies such as Verizon, AT&T, Sprint, and T-Mobile have turned to attractive teaser deals and exclusive phone arrangements with phone makers to offer the newest models of phones only with one wireless provider.

The use of teaser and lock-in strategies (such as preventing a person from keeping his or her phone when transferring wireless service to another provider) represents a new form of competition among network goods providers.

Is this competitive approach better than advertising? On the one hand, consumers today are not bombarded with telephone sales calls as they were in the 1990s, but on the other hand, the ability to switch from one provider to another has taken on additional switching costs.

Because network goods generally have a low marginal cost of production, firms have greater flexibility in segmenting their products to allow for a greater range of prices, each targeting a different subset of the market. Market segmentation strategies in network goods include versioning, intertemporal pricing, peak-load pricing, and bundling strategies.

versioning A pricing strategy that involves differentiating a good by way of packaging into multiple products for people with different demands.

Versioning refers to pricing strategies that involve differentiating a good by way of packaging it into multiple products for people with different needs. A common example is the choice of a wireless plan. Do you choose an unlimited monthly plan, a fixed-minute monthly plan, or a prepaid plan? A single firm can offer each of these plans and price each plan to attract the appropriate subset of customers.

intertemporal pricing A type of versioning in which goods are differentiated by the level of patience of consumers. Less patient consumers pay a higher price than more patient consumers.

A similar but slightly different strategy is intertemporal pricing. Like versioning, a firm uses intertemporal pricing strategies to target different groups of consumers by differentiating their product, but in this case, by time. Specifically, they use the fact that some consumers are more impatient than others to buy a product. For example, new books often first appear in bookstores as expensive hardcover editions, then as less expensive paperbacks several months later, followed by the availability of the book for loan from public libraries at no cost for the most patient consumers.

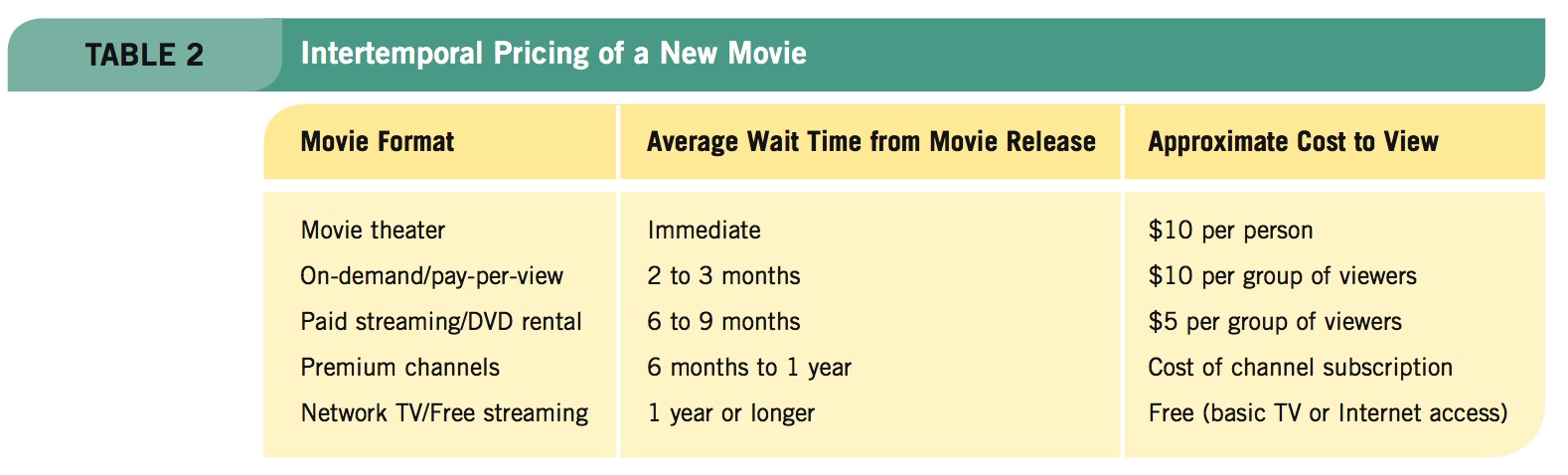

Another example of intertemporal pricing shown in Table 2 is the release of a new movie. A new movie first appears in theaters, followed by on-demand or pay-per-view, then via paid online streaming or DVD rental, then on premium movie channels, and lastly on network TV. With each step, the price to view the movie generally decreases.

Firms that successfully use versioning and intertemporal pricing can price discriminate among consumers by charging less patient consumers, who have lower elasticities of demand, higher prices than those consumers with more patience and higher elasticities of demand. Once consumers with less elastic demand are served, the price is dropped to serve those with more elastic demand. The firm earns more profit by versioning products using time as the differentiating factor.

peak-load pricing A versioning strategy of pricing a product higher during periods of higher demand, and lower during periods of lower demand.

Peak-load pricing focuses less on differentiating a product than it does on charging higher prices when there is greater demand for the product. For example, ticket prices for evening movies and Broadway shows typically are higher than prices for matinees. Most wireless plans come with free or highly discounted evening and weekend usage. And airlines typically charge less for tickets on the nonpeak travel days of Tuesday, Wednesday, and Saturday. Similar to versioning and intertemporal pricing, the use of peak-load pricing attempts to segment the market into consumers with less flexible demand and those with more flexible demand.

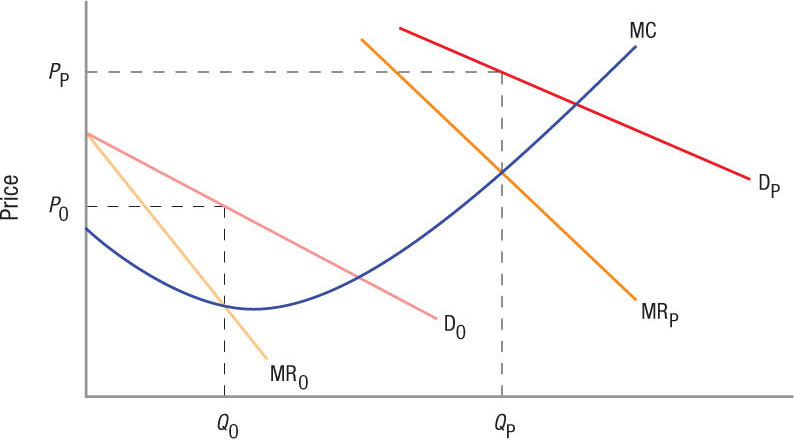

Figure 5 illustrates a market with peak-load pricing, where PP represents the higher prices charged during peak times when demand DP is greater, whereas PO is the lower price charged during off-peak times when demand DO is lower.

FIGURE 5

Peak-Load Pricing Demand curve DP represents a greater demand during peak periods, leading to an optimal price of PP. During off-peak times, demand DO is much lower, leading to a lower price of PO. Peak-load pricing can occur by time of day (telephone calls, live shows, movies), by day of the week (airline tickets), or by season (ski lift tickets).

bundling A strategy of packaging several products into a single product with a single price. Bundling allows firms to capture customers of related products by making it more attractive to use the same firm’s products.

Finally, network industries engage in bundling strategies to increase demand for related products. Because network goods generally have low marginal costs to produce, it does not cost the firm much to package several products together. Customers who purchase one product are then more likely to use other products from the same company, thus supporting the firm’s network and the value of all its goods. One example is Apple’s strategy of bundling many types of software into its Mac operating system. Bundled programs such as Safari, iMovie, iPhoto, iTunes, and Garage Band provide users with convenient “free” options, thereby reducing the need to use other network providers (such as Adobe and Real), which sell competing media products.

COMPETITION AND MARKET STRUCTURE FOR NETWORK GOODS

- Competition for market share in network goods is often intense as firms attempt to avoid the vicious cycle of a failed network good.

- Teaser strategies include attractive up-front savings to customers willing to switch to another network good provider, while lock-in strategies are used to make it more costly to leave a network good provider.

- Market segmentation involves separating consumers based on their elasticity of demand, with less patient consumers (those with inelastic demands) paying more than patient consumers with elastic demands.

- Versioning is the practice of differentiating a good into multiple products from which consumers can choose. Versioning also can be done by time (intertemporal pricing) or by peak usage (peak-load pricing).

- Firms bundle their goods because the marginal cost of adding additional products is minimal and the benefit from network effects is high if consumers use the included products instead of purchasing them separately from competing firms.

QUESTION: Why would a firm selling a network good choose to segment its customers by charging different prices? Wouldn’t it make more money by just charging everyone a high price?

A network good generally has a low marginal cost of production; therefore, any revenue a firm collects, even at low prices, typically increases its profit. By segmenting the market, the firm is separating customers based on their elasticity of demand. Customers with lower elasticities of demand are willing to pay a higher price than customers with higher elasticities of demand. Firms can segment the market by versioning their products. Products can be differentiated by time, peak usage, or bundling to create different versions of the same good at different prices.