Chapter Introduction

After studying this chapter you should be able to:

- Describe the difference between wealth and income.

- Describe the effects of life cycles on income.

- Analyze functional, personal, and family income distributions.

- Use a Lorenz curve and Gini coefficient to measure and describe the distribution of wealth and income.

- Describe the impact of income redistribution efforts.

- Describe the causes of income inequality.

- Describe the means for determining poverty thresholds.

- Describe the two measures for determining depth of poverty for families.

- Describe the prevailing theories on how to deal with poverty and income inequality.

On September 17, 2011, about 1000 protesters gathered in a small park near Wall Street in New York City to voice their concerns about social and economic inequality. What started as a local protest spurred by a social media campaign turned into a global movement known as Occupy.

The concerns raised by the Wall Street protesters and subsequently echoed by protesters in similar rallies in eighty-two countries on six continents dealt with a variety of issues relating to economic hardships that had been exacerbated during the recession of 2007–2009. Specifically, the Occupy movement claimed that the excessive influence of corporations on politics and the concentration of power by financial markets limited the opportunities of the majority of citizens in a democratic society. Supporters also lobbied for the right of citizens to have adequate access to health care, higher education, and a living wage. Above all, they are concerned about rising income inequality, which led to the coining of the slogan, “We are the 99%!” The slogan refers to the belief that economic prosperity has been unfairly concentrated among the richest 1% of the population, leaving the remaining 99% behind.

The issue of income inequality rose to the forefront in the United States as data showed that the richest 1% of the population earned nearly 20% of total income in 2012 and controlled over 40% of all wealth. This is a trend that is not slowing; inequality in the United States and around the world has expanded over the last three decades. Even during the last recession, when incomes of most Americans fell, the incomes of the richest Americans continued to rise.

What are the causes of income inequality? Two opposing theories exist. On the one hand, Occupy supporters claim that income inequality is the direct result of economic opportunities and tax policies that favor the wealthy few over the vast majority. The reductions in income and capital gains taxes on high-income earners in the United States are examples of how the tax structure became less progressive over time. On the other hand, others—including some prominent economists—believe that income inequality is the direct result of robust market incentives that reward entrepreneurial ability and success. These people do not believe income inequality is a result of some social injustice. Instead, they feel that wealth is the reward that comes from the opportunity for anyone to work hard, become successful, and be paid what they are worth to the economy.

Earlier, we saw that when input and product markets are competitive, wages are determined by worker productivity and the market value of output workers produce. This explains why some professional baseball players, who possess a unique ability to throw a 95-mph fastball and attract millions of fans, secure multimillion dollar contracts while teachers, who arguably perform a more valuable service but do so in a profession shared by millions of others with similar skills, earn salaries closer to the average.

Still, many people have trouble accepting that baseball pitchers earn millions, while teachers earn only thousands, and many others eke out subsistence wages. Income inequality is among the most contentious issues facing economists and other social scientists today.

Questions of fairness are normative. They can only be answered through individual value judgments. Economics has no right or wrong answers to offer in this area, but economists frequently contribute to these discussions.

Economic analysis gives us some insight into why income inequality exists. We have already seen how market power, unions, and discrimination can potentially skew income distribution. Even when public policy focuses on reducing these market imperfections, inequalities persist. Regardless of the causes of income inequality, addressing its effects requires special attention to those at the bottom of the income distribution: those who live in poverty.

This chapter looks at income inequality, its trends, its causes, and how it is measured. We then turn our attention to poverty, focusing on how poverty is traditionally measured, and the U.S. Census Bureau’s new approach to measuring poverty. Finally, we look at current poverty trends and the causes of poverty. Throughout this chapter, we use economic analysis to provide a framework for analyzing income distribution, poverty, and the public policies used to combat poverty.

Poverty and the Economy

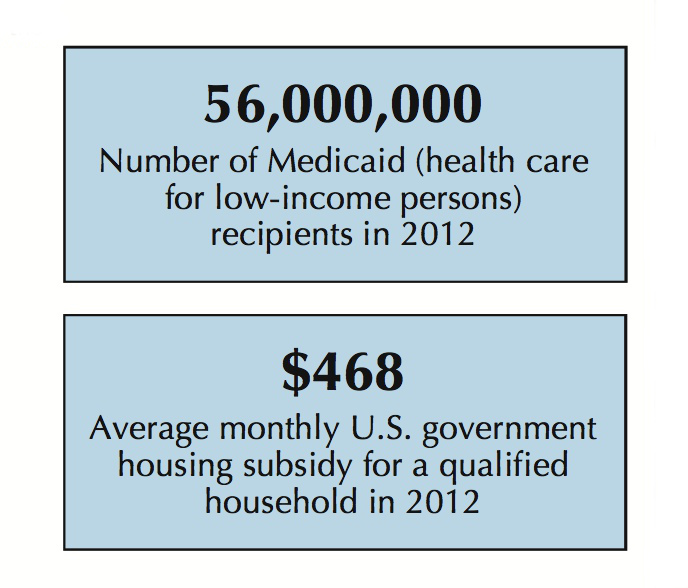

Poverty is a problem facing people in virtually all countries, both rich and poor. Each country uses different methods to address poverty, including assistance for food, housing, health care, and education.

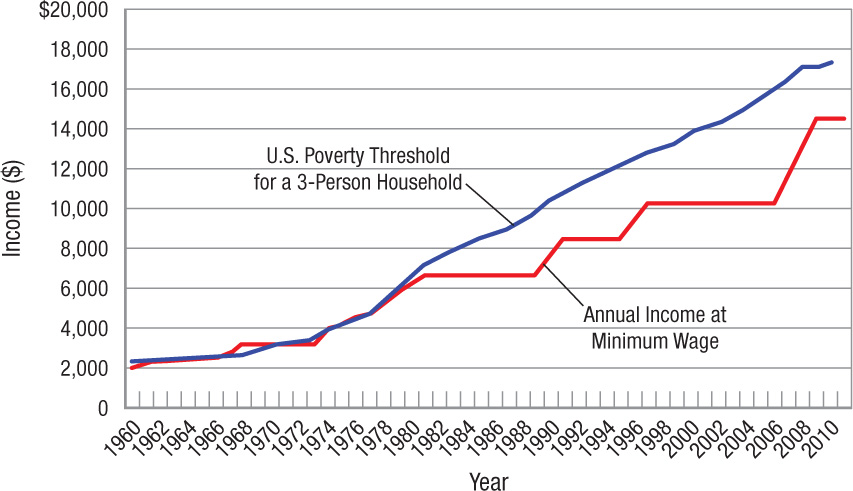

A single-parent working full time at the minimum wage is unable to keep a family out of poverty.

The U.S. federal minimum wage is an example of government policy aimed at curbing poverty. In the 1960s and 1970s, one person working a full-time job at minimum wage was roughly able to keep a family of three out of poverty. Since the 1980s, the minimum wage has not kept up.

Every country has its own measure of poverty, making a comparison of countries and their official poverty rate misleading. For example, Denmark and China both have an official poverty rate of 13.4%. In China, this means a family of four living on less than $1,400 a year; in Denmark, it means living on less than $45,000 a year plus having free health care, education, and retirement benefits.

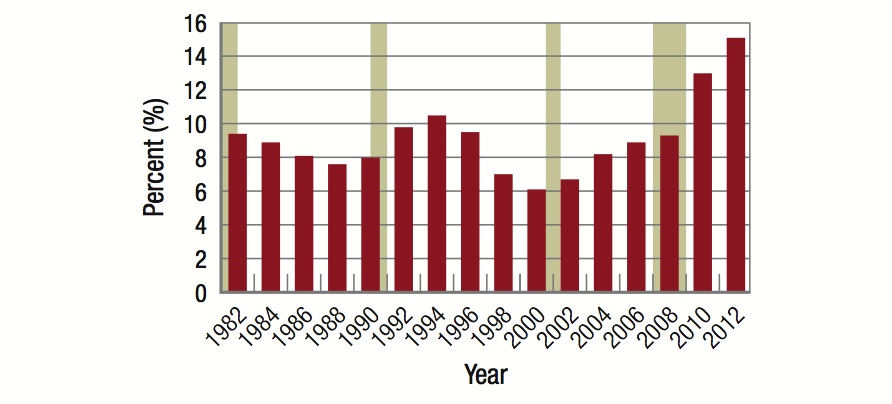

The percentage of Americans receiving food stamps fluctuates with the economy The last recession and slow recovery caused food stamp usage to rise.

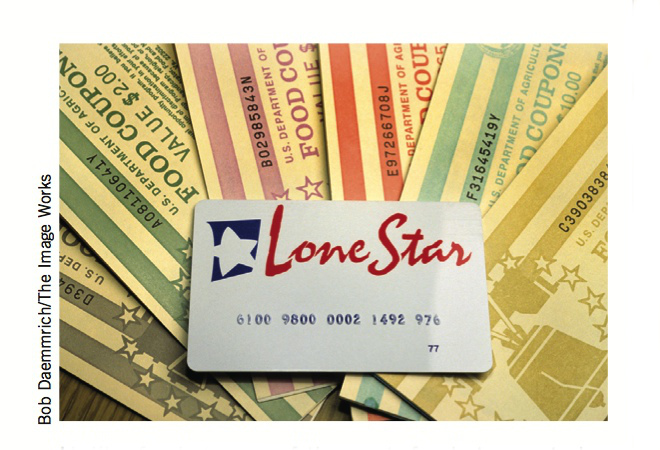

Unlike food stamps of the past, food stamps today work like a debit card.