Unemployment and the Economy

Inevitably, our economy will contain some unemployment. People who are reentering the workforce or entering it for the first time will often find that landing their first job can take some time. Then they may find, moreover, that taking the first available job is not always in their best interest—that it might be better to take the time to search for another position better matching their skills and personality. Getting information and searching more extensively can extend the period people remain unemployed.

Unemployment can occur because wages are artificially set above the market clearing or equilibrium wage. Both minimum wage laws and union bargaining can have this effect, helping those workers who are employed to earn more, but shutting some potential workers out of jobs.

Employers often keep wages above market equilibrium to reduce turnover, boost morale, and increase employee productivity. These efficiency wages give employees an incentive to work hard and remain with their present employers, because at other jobs they could get only market wages. These higher wages, however, can also prevent employers from hiring new workers, thus contributing to unemployment.

Changes in the business cycle will also generate unemployment. When the economy falls into a recession, sales decline, and employers are forced to lay off workers, therefore unemployment grows.

Separating different types of unemployment into distinct categories will help us apply unemployment figures to our analysis of the economy.

Types of Unemployment

There are three types of unemployment: frictional, structural, and cyclical. Each type has different policy ramifications.

Frictional Unemployment Do you recall how many different part-time jobs you held during high school? How about summer jobs while in college? If you have worked several types of jobs, you’re not alone, as many reasons exist why one may leave a job. You may get bored; the business may close or reduce the staff it needs; you might move to a new city; or you could have been fired. If you’re enrolled in school while working part-time jobs, generally you are not considered unemployed while between jobs, because being in school generally means you’re not counted in the labor force. But the reasons for changing jobs are still relevant once you graduate and work full time.

frictional unemployment Unemployment for any economy that includes workers who voluntarily quit their jobs to search for better positions, or are moving to new jobs but may still take several days or weeks before they can report to their new employers.

As you pursue your career, chances are that you’ll work for more than one company during your lifetime. Frictional unemployment describes the short-term duration of unemployment caused by workers switching jobs, often voluntarily, for a variety of reasons. Some workers quit their jobs to search for better positions. In some cases, these people may already have other jobs, but it may still take several days or weeks before they can report to their new employers. In these cases, people moving from one job to the next are said to be frictionally unemployed.

structural unemployment Unemployment caused by changes in the structure of consumer demands or technology. It means that demand for some products declines and the skills of this industry’s workers often become obsolete as well. This results in an extended bout of unemployment while new skills are developed.

Frictional unemployment is natural for our economy and, indeed, necessary and beneficial. People need time to search for new jobs, and employers need time to interview and evaluate potential new employees.

Structural Unemployment Structural unemployment is roughly the opposite of frictional unemployment. Whereas frictional unemployment is assumed to be of rather short duration, structural unemployment is usually associated with extended periods of unemployment.

Structural unemployment is caused by changes in the structure of consumer demands or technology. Most industries and products inevitably decline and become obsolete, and when they do, the skills honed by workers in these industries often become obsolete as well.

Declining demand for cigarettes, for instance, has changed the labor market for tobacco workers. Farm work, textile finishing, and many aspects of manufacturing have all changed drastically in the last several decades. Farms have become more productive, and many sewing and manufacturing jobs have moved overseas because of lower wages there. People who are structurally unemployed are often unemployed for long periods and then become discouraged workers.

cyclical unemployment Unemployment that results from changes in the business cycle, and where public policymakers can have their greatest impact by keeping the economy on a steady, low-inflationary, solid growth path.

To find new work, those who are structurally unemployed must often go through extended periods of retraining. The more educated those displaced are, the more likely they will be able to retrain easily and adjust to a new occupation. One benefit of a growing economy is that retraining is more easily obtained when labor markets are tight.

Cyclical Unemployment Cyclical unemployment is the result of changes in the business cycle. If, for example, business investment or consumer spending declines, we would expect the rate of economic growth to slow, in which case the economy would probably enter a recession, as we will examine in later chapters. Cyclical unemployment is the difference between the current unemployment rate and what it would be at full employment, defined below.

Frictional and structural unemployment are difficult problems, and macroeconomic policies provide only limited relief. Cyclical unemployment, most economists agree, is where public policymakers can have their greatest impact. By keeping the economy on a steady, low-inflationary, solid growth path, policymakers can minimize the costs of cyclical unemployment. Admittedly, this is easier said than done given the various shocks that can affect the economy.

Defining Full Employment

Economists often describe the health of the economy by comparing its performance to full employment. We know full employment cannot be zero unemployment, because frictional and structural unemployment will always be present. Full employment today is generally taken to be equivalent to the natural rate of unemployment.

natural rate of unemployment That level of unemployment at which price and wage decisions are consistent; a level at which the actual inflation rate is equal to people’s inflationary expectations and where cyclical unemployment is zero.

The Natural Rate of Unemployment The natural rate of unemployment has come to represent several ideas to economists. First, it is often defined as that level of unemployment at which price and wage decisions are consistent—a level at which the actual inflation rate is equal to people’s inflationary expectations. Natural unemployment is also considered to be the unemployment level at which unemployment is only frictional and structural, or cyclical unemployment is zero.

Economists often refer to the natural rate of unemployment as the nonaccelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU), defined as the unemployment rate most consistent with a low rate of inflation. It is the unemployment level at which inflationary pressures in the economy are at their minimum. We will discuss these issues in greater detail throughout the remainder of the book. For now, it is enough to remember that the NAIRU is the unemployment rate consistent with low inflation and low unemployment.

Full employment, or the natural rate of unemployment, is determined by such institutional factors as the presence or absence of employment agencies and their effectiveness. Many job seekers today, for example, search online postings on sites such as Indeed or LinkedIn, reducing the time it takes to match available employees with prospective employers. Other factors might include the demographic makeup of the labor force and the incentives associated with various unemployment benefit programs and income tax rates.

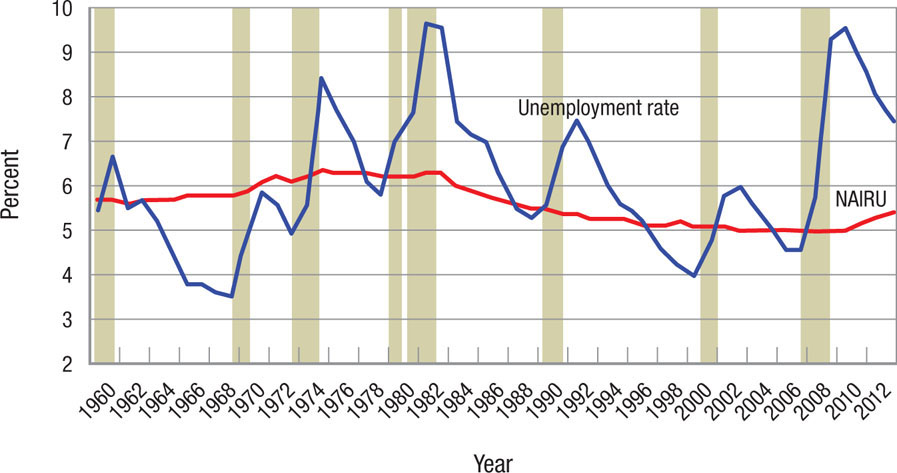

Changes in the Unemployment Rate Around the NAIRU In the previous chapter we studied how the business cycle leads to both periods of high economic growth and periods of recessions, fluctuating around a long-term trend. The unemployment rate follows a similar pattern, rising during recessions and falling during economic booms, but fluctuating around the NAIRU. In the United States, the NAIRU is very steady and has fallen slowly over the past 30 years from about 6% to roughly 5%, largely due to improvements in labor market efficiencies (such as the use of the Internet in job searches and the increase in part-time and temporary work) that has reduced the unemployment rate associated with low inflation.

Of particular importance is the length of time it takes the unemployment rate to return to the NAIRU when recessions push unemployment higher. To analyze this point, Figure 4 shows the unemployment rate over the past 50 years, along with the NAIRU. Periods of recession are shaded, most indicating cyclical unemployment as the unemployment rate line rises above the NAIRU. It is interesting to note that the time it takes the unemployment rate to return to the NAIRU varies. In most economic recoveries prior to 1990, the unemployment rate returned to the NAIRU fairly quickly. The 1990–1991 and 2001 recessions did not produce much cyclical unemployment; however, the unemployment rate initially rose during the recovery, leading to a “jobless recovery.” But the longest jobless recovery occurred after the 2007–2009 recession, in which the unemployment rate stayed well above the NAIRU for several years.

FIGURE 4

Unemployment Rate Versus the NAIRU The average unemployment rate and NAIRU are shown from 1960 to 2013. Periods of recession are shaded. The rising unemployment line and flatter downward slopes following the last three recessions indicate a longer recovery period for jobs caused by the jobless recovery.

Jobless Recoveries Prolong Unemployment Above NAIRU The previous chapter discussed some of the reasons why unemployment can stay high for so long after a recession is deemed over. It highlighted the four key markets—labor, financial, capital, and output—that influence one another and affect job growth. But the puzzle that economic growth does not coincide with job growth also deserves an explanation.

Why Do Unemployment Rates Differ So Much Within the United States?

In July 2013, the U.S. unemployment rate was 7.4%. However, in Nevada it was 9.5%. Meanwhile, in North Dakota, it was only 3.0%. Looking at metropolitan area unemployment rates reveals even starker differences: The unemployment rate in Yuma, Arizona, was 30.1%, while in Bismarck, North Dakota, it was 2.8%. Why do such large differences in unemployment exist between states and between cities?

In Europe, where citizens of the European Union are free to live and work in any other country within the union, differences in unemployment rates between member countries remain largely due to cultural reasons. People are hesitant to move to a country where people speak a different language or have a different culture. But in the United States, language and cultural issues between states are considerably less than between European countries—English is the primary language and Americans all basically watch the same types of movies and television shows.

Aside from the common language and culture, differences do arise in other areas, which helps to explain the differences in unemployment rate.

First, differences in taxes and regulations exist between states. Some states have lower taxes than others, and some states have environmental and work rules that are more business friendly than others.

Second, many industries tend to form a cluster in order to take advantage of economies of scale and scope. For example, industrial agglomeration in the computer industry centers in greater San Jose (“Silicon Valley”). Detroit has long been the automobile capital of the country, while Gary, Indiana, was once a major steel-producing town (in addition to being the birthplace of Michael Jackson). Economic trends tend to favor some industries over others. Biotechnology, eCommerce, and health care industries have experienced much growth over the past decade, leading to employment growth in cities home to these industries. However, declines in manufacturing have increased unemployment in certain industrial clusters.

Finally, and perhaps most obvious, is that people prefer certain geographic areas to others. Significant population growth has occurred in the South and Mountain West, where warm weather and scenic beauty await, respectively. Many immigrants from Mexico prefer living in states bordering Mexico for cultural reasons. And throughout much of the past century, people have moved from rural areas to urban areas. How much would you sacrifice to live in a preferred area? People ask themselves this question often.

In the labor market, recessions tend to send people looking for other options—going back to college, seeking early retirement, or just taking time off until the economy improves. Some who are out of work during these periods take temporary or part-time jobs to support their loved ones until better work can be found. Although all of these people’s jobs were affected, the government does not consider them as unemployed, because they had either found temporary work or had left the labor force to pursue other options. Thus, the official unemployment rate reported during recessions tends to underestimate the actual number of people seeking work, a problem discussed in the previous section.

During an economic recovery, as jobs are being created, not only do the unemployed seek these jobs, but many of those who had left the labor force return to compete for these same jobs. When many would-be workers choose to leave the workforce during a prolonged economic downturn, competition for jobs can be more severe during an economic recovery when these workers return to the labor force.

The last few recessions saw many people temporarily leave the workforce to pursue nonwork options such as schooling, stay-at-home parenting, or volunteer work. These choices may explain why unemployment is slow to fall during economic recoveries, and one of the major reasons why jobless recoveries might remain a feature in future recessions.

Inflation, employment, unemployment, and gross domestic product (GDP) are the key macroeconomic indicators of our economic health. Our rising standards of living are closely tied to GDP growth. In the next chapter, we will investigate what causes our economy and living standards to grow over the long term.

UNEMPLOYMENT AND THE ECONOMY

- Frictional unemployment is inevitable and natural for any economy as people change jobs and businesses open and close.

- Structural unemployment is typically caused by changes in consumer demands or technology. It is typically of long duration and often requires that the unemployed become retrained for new jobs.

- Cyclical unemployment is the result of changes in the business cycle. When a recession hits, unemployment rises, then falls when an expansion ensues.

- Macroeconomic policies have the most effect on cyclical unemployment.

- Full employment is typically defined as that level at which cyclical unemployment is zero or that level associated with a low nonaccelerating inflation rate.

QUESTION: The financial industry experienced a rapid expansion in the middle of the last decade as a result of the housing bubble, which created jobs for millions of workers in banks, mortgage companies, financial advising companies, and insurance companies. When the bubble burst, many of these workers became unemployed as the financial industry retrenched. For many, their skills were so specialized that they were unable to find new jobs at their old salaries. Were these people frictionally, structurally, or cyclically unemployed? Explain.

Many workers became structurally unemployed because the skills they had acquired for the financial industry (and in many cases, specific to the housing industry) were not as useful in other industries. Therefore, as the financial industry became smaller after the housing bubble burst, many workers needed to find work in other industries, which required learning a new skill set.