Thinking About Short-Run and Long-Run Economic Growth

Up to this point, we have discussed why economic growth is good and how it is measured. Next, we need to discuss the differences between short-run and long-run growth and the factors that determine economic growth.

Short-Run Versus Long-Run Growth

The first step to understanding how growth occurs is to understand the difference between short-run and long-run growth.

Short-Run Growth Involves a Fixed Capacity Short-run growth occurs when an economy makes use of existing but underutilized resources. For example, abandoned shopping centers or malls could easily be reopened with new stores. Idle construction equipment and unemployed workers could quickly be put into use on a new project. In these cases, the resources to produce goods and services are available but are not being used.

Short-run growth is common when countries are recovering from an economic downturn, or when obstacles preventing resources from being fully used (such as restrictions on land use or high mandatory benefits for workers) are loosened. But to sustain growth beyond the small fluctuations common in the business cycle, efforts to expand an economy’s ability to produce are necessary. This leads to long-run growth.

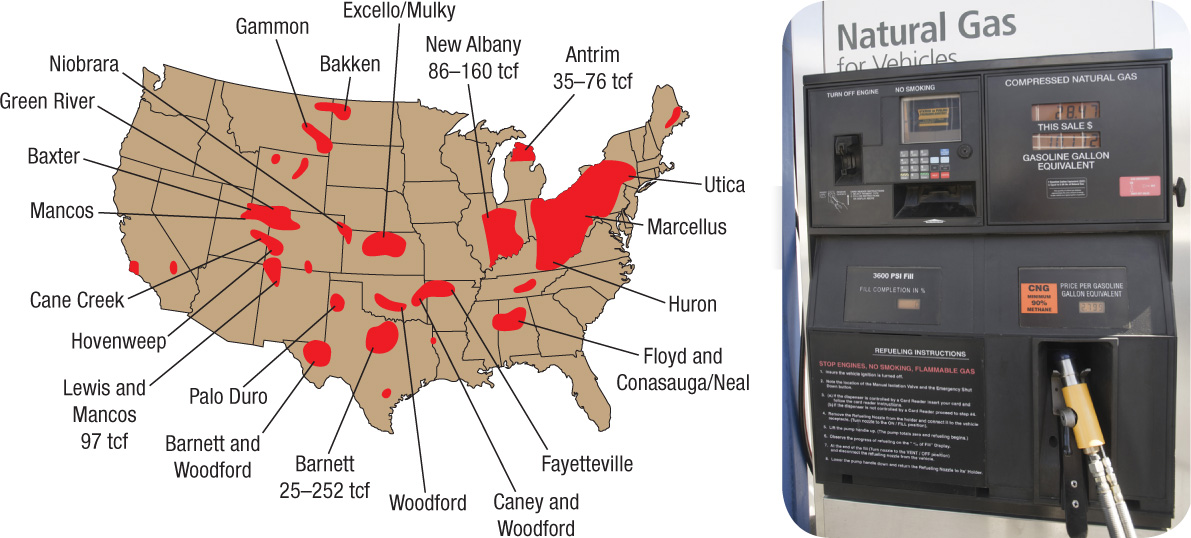

Long-Run Growth Involves Expanding Capacity Long-run growth occurs when an economy finds new resources or finds ways to use existing resources better. In other words, the capacity to produce goods and services increases, leading to long-run growth. For example, suppose natural gas deposits that are estimated to be abundant in the United States are explored, leading to an expansion in production of natural gas powered vehicles (NGVs). This may lead to an expansion of production capacity in the United States through the reduction of its dependence on foreign oil and through the development of more environmentally friendly cars.

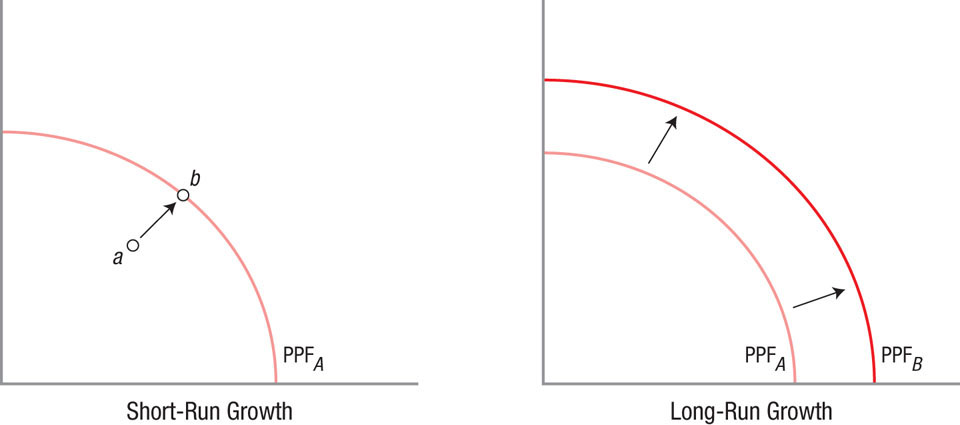

In Chapter 2, we introduced production possibility frontiers (PPF) to illustrate the maximum productive capacity of an economy if all resources are fully utilized. We can use PPF diagrams to show the difference between short-run and long-run economic growth.

In Figure 1, the left panel shows an economy initially producing at point a inside of its PPF, indicating underutilized resources such as idle equipment or excess labor. By putting these resources to work, an economy can work its way toward production capacity on the PPF line at point b, representing short-run growth. Long-run growth, illustrated in the right panel, requires an economy to find new resources such as new natural resources or improved human capital in its workforce, or new ideas to make better use of existing resources. Such improvements in production capacity will shift PPFA outward to PPFB, allowing for more production possibilities.

FIGURE 1

Short-Run Versus Long-Run Growth Illustrated on PPF Diagrams Short-run economic growth occurs when underutilized resources are placed into production. In a PPF diagram, this is shown as a movement from a point inside the PPF to a point closer to or on the PPF (such as from a to b). Long-run economic growth occurs when new resources are found or existing resources are used more efficiently, thus expanding an economy’s capacity to produce. In this case, PPFA expands outward to PPFB, allowing for more production possibilities.

Factors of Production

Achieving long-run growth requires an economy to acquire new resources or to find better ways to use the resources it has to generate goods and services people desire either domestically or abroad through trade. In Chapter 2, we introduced these resources as the four factors of production, which are the building blocks for production and economic growth. Let’s review these factors of production.

1. Land and natural resources (denoted as “N”) includes land and any raw resources that come from land, such as mineral deposits, oil, natural gas, and water.

2. Labor (denoted as “L”) includes both the mental and physical talents of people. Human capital (denoted as “H”) includes the improvements to labor capabilities from training, education, and apprenticeship programs.

3. Physical capital (denoted as “K”) includes all manufactured products that are used to produce other goods and services. This includes machinery used in factories, cash registers in stores and restaurants, and communications networks used to track shipments.

4. Entrepreneurial ability, technology, and ideas (A) describe the ability to take resources and use them in creative ways to produce goods and services. For example, technology improves the productivity of all factors, and therefore is considered a highly valuable input in production. In other words, land, labor, and physical capital are not useful unless the idea of how to turn these resources into goods and services people want exists.

When factors of production are used to produce goods and services useful for consumption, a measurement tool is needed to calculate the extent to which inputs (resources) are turned into outputs (goods and services). The relationship between the amount of inputs used in production and the amount of output produced is called a production function.

Production Function

production function Measures the output that is produced using various combinations of inputs and a fixed level of technology.

A production function shows the output that is produced using different combinations of inputs combined with existing technology. Although many types of production functions exist, most are variations of the classical form: Output = f(L, K), which means that output is determined by some function of available labor or capital.

Every country, industry, and even firm can have a different production function that measures how much output it can produce given the physical inputs and technology available. No two countries will produce exactly the same type or amount of products given the resources they have. Thus, a production function is a very important tool used to determine whether a country is using its limited resources efficiently and to what extent it can experience long-run growth.

Suppose f(L, K) = L + K for simplicity. This means that if an economy has 10 units of labor and 10 units of capital, total output would equal 10 + 10 = 20. Although most production functions are not this simple, the idea is that more inputs can produce more output by some function.

Because inputs are not limited to just labor and capital, a more realistic production function would look like the following:

Output = A × f(L, K, H, N)

where total output equals technology (A) times a function of available labor (L), physical capital (K), human capital (H), and land and natural resources (N).

This equation helps to explain how an entire economy grows. For example, having a more educated labor force or having more capital will contribute to higher productive capacity of the economy (shifting the PPF outward).

But what we are truly interested in is how growth affects the lives of people living in those countries. For example, India’s GDP has grown at a very fast pace, but so has its population. The important question is how economic growth affects the standard of living of the average person, or output per person. One way to achieve a close (but not exact) measure of output per person is to revise the above production function to one that measures output per worker.

To do so, assume that the production function exhibits constant returns to scale (a reasonable assumption). This means that any proportional change in the number of inputs results in the same proportional change in output. For example, if we divide all inputs by L, we would be able to calculate the output per worker as follows:

Output per worker = A × f(L/L, K/L, H/L, N/L)

JOSEPH SCHUMPETER (1883–1950)

Joseph Schumpeter drew attention to the critical role of the entrepreneur in the process of economic development. He famously coined the term “creative destruction” to describe the innovative dynamism of capitalism but came to the surprising conclusion that the system he exalted was ultimately doomed by the forces it helped create.

Born in Triesch, Moravia, in 1883, Schumpeter studied law and economics at the University of Vienna. In 1932, he emigrated to the United States, where he became an influential economics professor at Harvard University.

Schumpeter was a confirmed elitist who suffered from self-doubt and depression. Although he enjoyed telling audiences that he “aspired to become the greatest economist, horseman, and lover in the world,” he would then throw in the punchline, “but things are not going well with the horses.” Even though his career was in the shadow of the more famous John Maynard Keynes, he considered himself to be the greater economist.

In 1939, he published Business Cycles, which linked entrepreneurial activity to business cycles. He identified “waves of innovation,” and paradoxically, connected innovation with the downturns or depressions in the business cycle, as new products competed with the old. Depressions, in his view, were part of the process of adapting to new innovations.

In 1942, Schumpeter published Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, considered by many to be his masterpiece. He wrote about the future of capitalism, which he described as creative destruction. The influence of Schumpeter’s work is still seen today in the study of modern growth theory.

Sources: Thomas McCraw, Prophet of Innovation: Joseph Schumpeter and Creative Destruction (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press), 2007; Paul Strathern, A Brief History of Economic Genius (New York: Texere), 2001.

This equation shows that output per worker equals technology times a function of physical capital per worker, human capital per worker, and land and natural resources per worker. Because we are concerned with output per worker, having more people will not automatically lead to a better standard of living (hence, L/L = 1). However, having more capital per person or more human capital (education) will increase the productivity of labor as each worker produces more output. Therefore, increases in capital will lead to improved standards of living.

To this point, we have discussed the importance of economic growth and defined the building blocks for economic growth using the factors of production that enter into the production function. The next section will use the production function to discuss ways in which an economy achieves growth by way of increasing productivity.

THINKING ABOUT SHORT-RUN AND LONG-RUN ECONOMIC GROWTH

- Short-run growth occurs from using resources that have been sitting idle or underutilized, and is represented in a PPF diagram as a movement from a point within the PPF toward the PPF.

- Long-run growth occurs when the productive capacity of an economy is expanded through more resources or better uses of existing resources, and is shown in a PPF diagram as an outward shift of the PPF.

- The primary factors of production are land and natural resources, labor (and human capital), physical capital, and technology (entrepreneurial ability and ideas).

- A production function measures the amount of output that can be produced using different combinations of inputs. Production functions vary by firms, industries, and countries.

- Output per person adjusts the production function for changes in population growth in a country.

QUESTION: The Ivory Coast (Côte d’Ivoire) in West Africa is a country with abundant natural resources, a long coastline, and a stable currency that is tied to the euro and managed by the French Treasury. Despite these benefits, it remains an extremely poor country with an unstable government. What does this finding suggest about the Ivory Coast’s overall factors of production and its production function compared to a country, say Iceland, with fewer physical resources but a significantly higher standard of living?

Every factor of production contributes to economic growth. Although the Ivory Coast is abundant in natural resources and labor compared to Iceland, it lacks the human capital, physical capital, and technology that are important components in the production function. In addition, the lack of stability in the country from recent civil and military strife has left many of its resources underutilized for productive purposes, further inhibiting the Ivory Coast from achieving higher long-run growth.