Chapter Introduction

181

182

After studying this chapter you should be able to:

- Name the components of aggregate spending.

- Analyze consumption using the average propensity to consume (APC) and the marginal propensity to consume (MPC).

- Analyze savings using the average propensity to save (APS) and the marginal propensity to save (MPS).

- Describe the determinants of consumption, saving, and investment.

- Determine macroeconomic equilibrium in the simple aggregate expenditures model of the private domestic economy.

- Explain why, at equilibrium, injections equal withdrawals in the economy.

- Explain the multiplier process, how it is computed, and why it operates in both directions.

- Describe macroeconomic equilibrium in the full aggregate expenditures model when government and the foreign sectors are added.

- Explain why the balanced budget multiplier is equal to 1.

- Describe the differences between recessionary and inflationary gaps.

Madawaska, Maine, near the northern end of U.S. 1 that extends all the way south to Key West, Florida, is like many other idyllic small towns in America— picturesque, friendly, and highly dependent on one industry to provide jobs for its residents. For Madawaska, it is the local paper mill, which provides jobs to 650 of its 4,500 residents. The salaries earned by its workers help to keep the rest of the town employed, including workers in restaurants and cafés, pharmacies, banks, and gas stations that serve the paper mill workers and their families.

During the depth of the 2007–2009 recession, when Madawaska’s paper mill was on the brink of closure, not only did its workers face potential unemployment, but so did the rest of the community, which depends on people with jobs at the paper mill to support their businesses. Towns such as Madawaska highlight the interdependency of the economy in which the loss of one job results in a reduction in spending that affects other jobs. In February 2010, the workers at the paper mill took the unusual step of accepting an 8.5% wage cut in order to keep the company (and town) from closing down.

The real economic crisis of Madawaska has been seen in recent years throughout the U.S. economy, in cities big and small, as the recession and slow recovery led to high unemployment and low income growth, which subsequently led to less money being spent on clothing, electronics, travel, and cars, causing a chain reaction downward in consumption. This chain reaction is what John Maynard Keynes alluded to when he published The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money in 1936, which discussed the importance of aggregate spending and the government’s role in stabilizing the macroeconomy.

Today, the ideas of John Maynard Keynes are frequently in the news. The phrase “Government Must Act!” is echoed by people of all political views when facing economic hard times. But how should government act and to what extent should it act?

These are the more contentious questions that are debated today. Stimulus packages, tax cuts, farm subsidies, laws and regulations, and even financial aid for college students are all part of a huge arsenal of tools available to government policymakers.

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 was one such stimulus policy passed by Congress. Among its efforts to boost economic activity and to create jobs were money designated for construction projects, tax cuts for most workers, and an increase in unemployment benefits. The goal of the stimulus was to put money into the hands (through jobs, tax cuts, and cash benefits) of those most likely to spend it in their communities, thus carrying a positive ripple effect through to other businesses that depend on consumer spending.

But Keynesian policies have not been without their critics as the size of government grew. Spending by government (federal, state, and local) has increased from 10% of GDP in the 1930s to over 30% today as the size and scope of government programs expand. Although many people benefit from these programs, some believe government has overreached and they would prefer something smaller and simpler.

This sort of thinking is not new. In fact, over a century ago, government policies were rarely used to intervene in the workings of the economy, even when the economy entered a downturn. Classical economists, as they are called, viewed the role of the government as providing the necessary framework upon which the market could operate—maintaining competition, providing central banking services, providing for national defense, administering the legal system, and so forth. But government was not expected to play a role in promoting full employment, stabilizing prices, or stimulating economic growth—the economy was supposed to do this on its own. The belief at the time was that economic downturns were self-correcting, meaning that if the economy were left alone, the forces of supply and demand would naturally bring the economy back into equilibrium.

To classical economists, this is how the self-correcting mechanism worked. Suppose a lack of consumer confidence caused surpluses in the product markets. Businesses would lower prices to get the goods out the door, bringing product markets back into equilibrium. Lower prices pinch profit margins, therefore businesses would seek to lower costs, the chief of which is labor. Just as the paper mill workers in Madawaska took a pay cut in order to keep their jobs, workers (in the classical view) would take pay cuts to deal with price adjustments in product markets. This is the self-correcting mechanism in product and labor markets.

183

The Role of Spending in the Economy

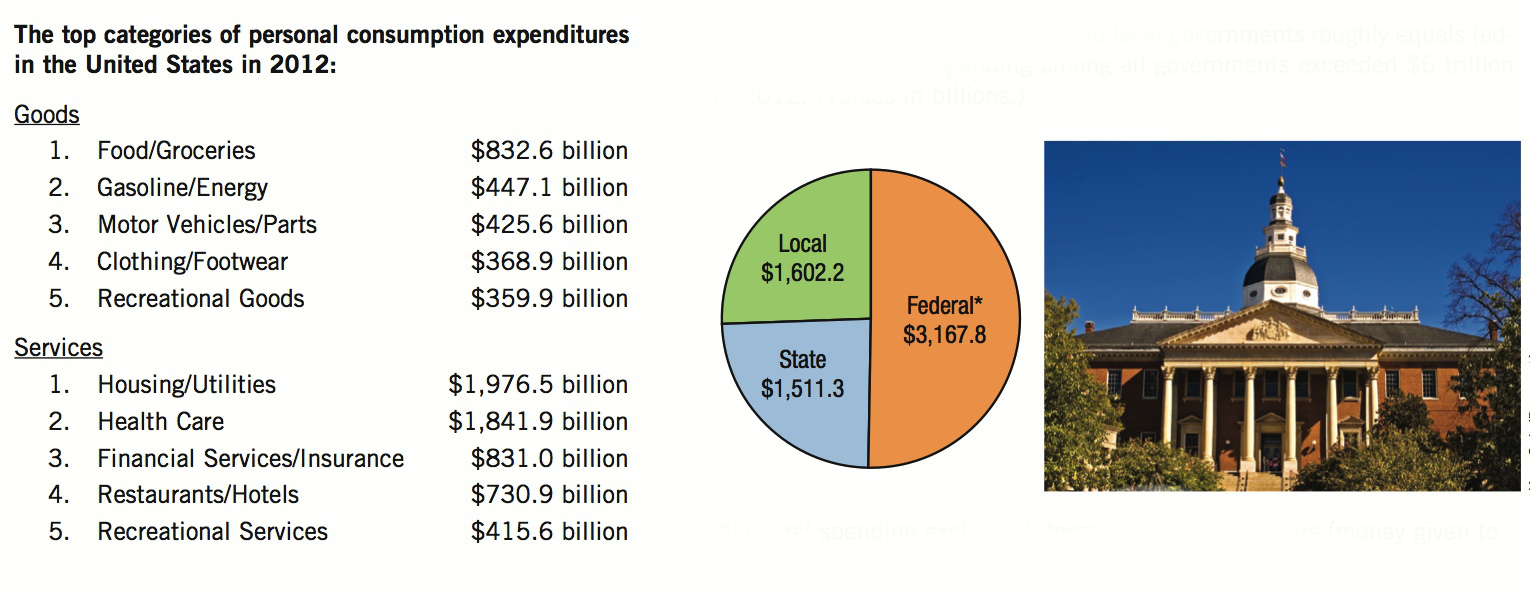

Spending plays a vital role in spurring economic activity and creating growth and jobs. Spending occurs by consumers, investors, foreigners, and government. During economic downturns, government plays an increasingly important role in trying to influence the economy.

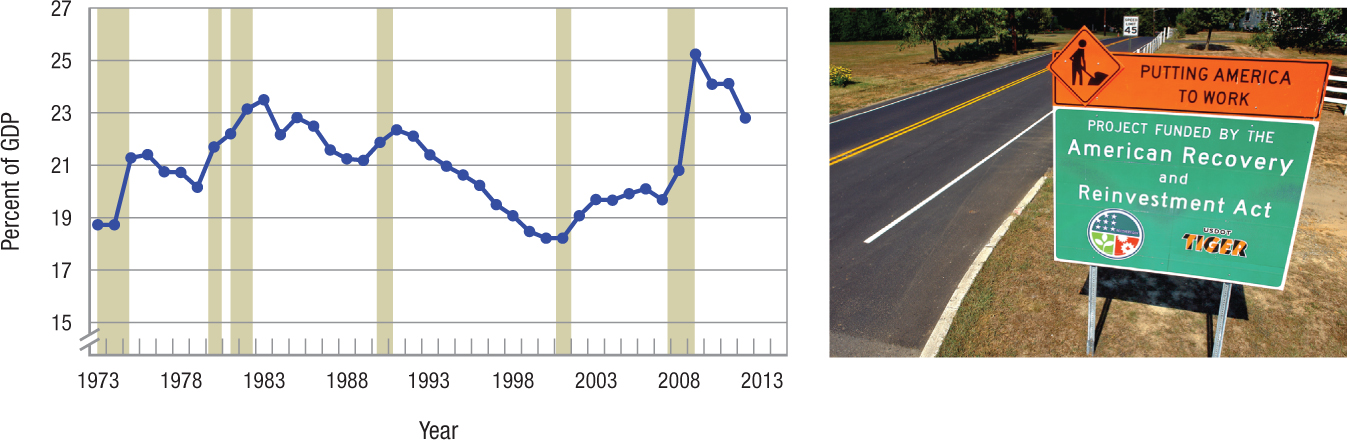

Government spending as a percentage of GDP rises during economic recessions (shaded).

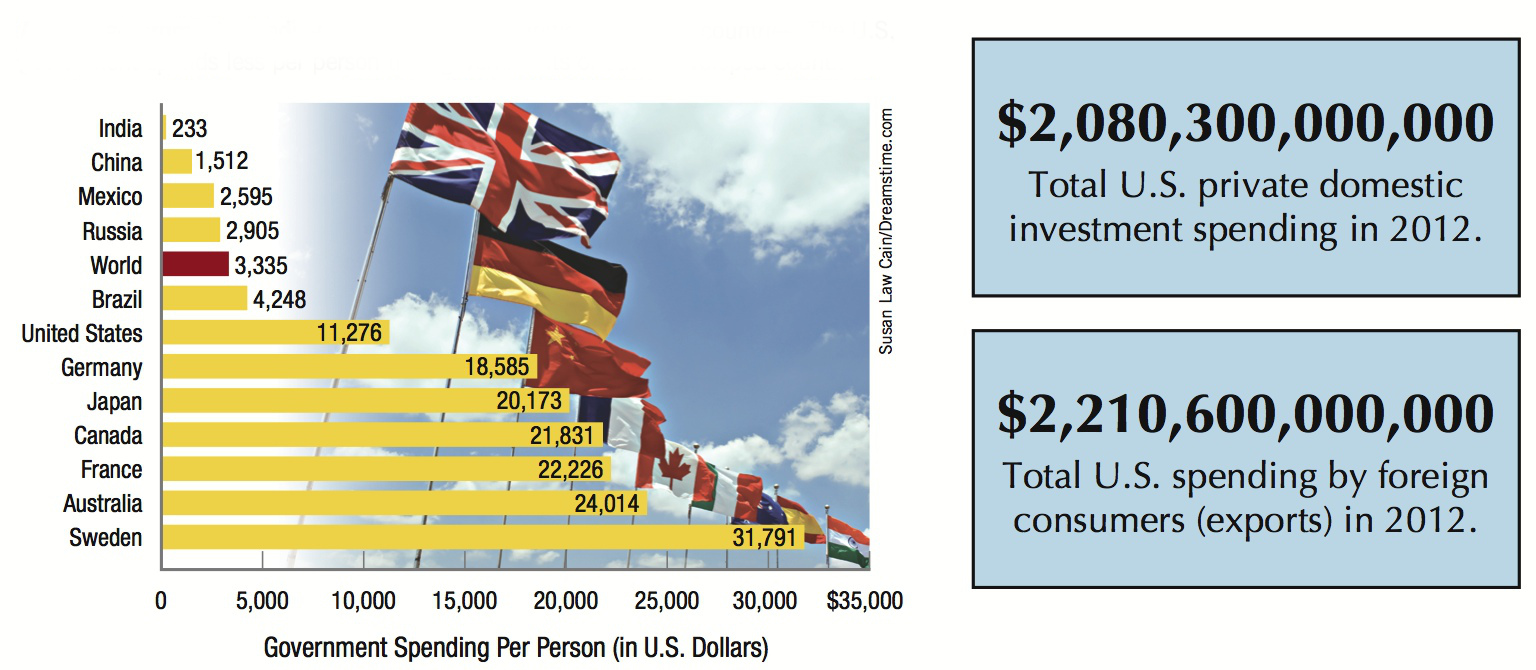

Average government spending per person varies significantly across countries. The U.S. government spends less per person than governments of other developed countries.

Combined spending among state and local governments roughly equals federal spending. Total spending among all governments exceeded $6 trillion in 2012. (Values in billions.)

*Federal spending excludes intergovernmental transfers (money given to state and local governments).

184

What about capital markets? In the classical view, savings (and by extension, consumption) and investment are determined by interest rates. If investment is too low relative to saving, interest rates would fall, reducing saving and stimulating business investment. In this way, capital markets worked with product and labor markets to keep the economy chugging away at full employment.

That classical perspective was challenged during the Great Depression by Keynes, who turned away from the classical framework with its three separate and distinct competitive markets operating through prices, wages, and interest rates. He focused instead on the economy as a whole and on aggregate spending.

In this chapter, we develop the aggregate expenditures model, which is commonly referred to as the Keynesian model. It can be used to analyze short-run macroeconomic fluctuations. This model will give you the tools to understand why policymakers took such an aggressive approach to the 2007–2009 downturn. Keynes’s focus was on aggregate spending, and how consumption spending is a key component to explaining how the economy reaches short-term equilibrium employment, output, and income. Using this model, we will see why an economy can get stuck in an undesirable place, and why policies are useful in smoothing out the business cycle.