The Simple Aggregate Expenditures Model

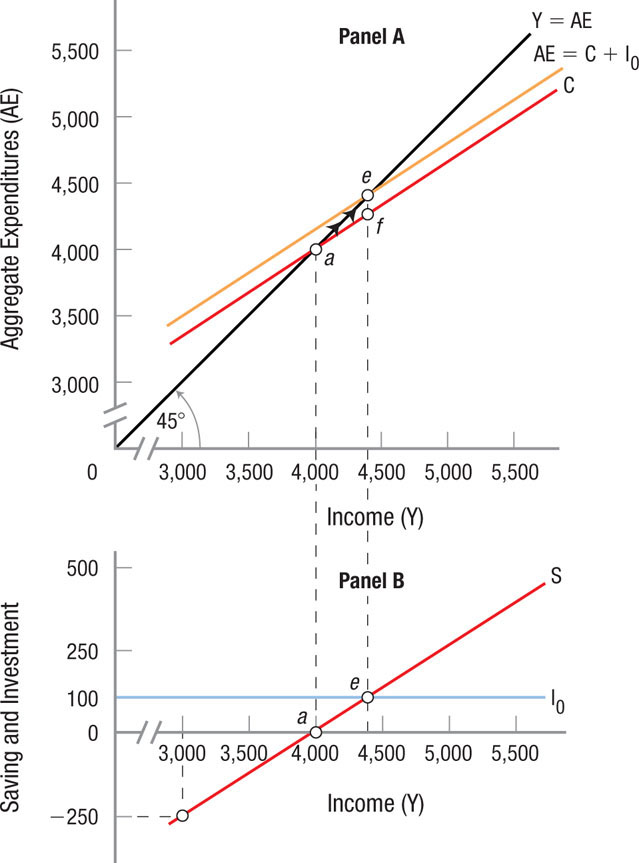

Now that we have stripped the government and foreign sectors from our analysis at this point, aggregate expenditures (AE) will consist of the sum of consumer and business investment spending (AE = C + I). Figure 5 shows a simple aggregate expenditures model based on consumption and investment. Aggregate expenditures based on the data in Table 1 are shown in panel A of Figure 5; panel B shows the corresponding saving and investment schedules.

Let us take a moment to remind ourselves what these graphs represent. The 45° line in Panel A represents the situation when income exactly equals spending, or Y = AE. In other words, no savings occur at any level of income. All other lines represent situations in which income does not exactly equal spending at all levels of income. Point a in both panels is that level of income ($4,000) at which saving is zero and all income is spent. Saving is, therefore, positive for income levels above $4,000 and negative at incomes below. The vertical distance ef in panel A represents investment (I0) of $100; it is equal to I0 in panel B. Note that the vertical axis of panel B has a different scale from that of panel A.

Macroeconomic Equilibrium in the Simple Model

Keynesian macroeconomic equilibrium In the simple model, the economy is at rest; spending injections (investment) are equal to withdrawals (saving), or I = S, and there are no net inducements for the economy to change the level of output or income. In the full model, all injections of spending must equal all withdrawals at equilibrium: I + G + X = S + T + M.

The important question to ask is where this economy will come to rest. Or, in the language of economists, at what income will this economy reach Keynesian macroeconomic equilibrium? By equilibrium, economists mean that income at which there are no net pressures pushing the economy to move to a higher or lower level of income and output.

To find this equilibrium point, let’s begin with the economy at an income level of $4,000. Are there pressures driving the economy to grow or decline? Looking at point a in panel A of Figure 5, we see that the economy is producing $4,000 worth of goods and services and $4,000 in income. At this income level, however, consumers and businesses want to spend $4,100 ($4,000 in consumption and $100 in investment). Because aggregate expenditures (AE) exceed current income and output, there are more goods being demanded ($4,100) than are being supplied at $4,000. As a result, businesses will find it in their best interests to produce more, raising employment and income and moving the economy toward income and output level $4,400 (point e).

FIGURE 5

Equilibrium in the Aggregate Expenditures Model Ignoring government spending and net exports, aggregate expenditures (AE) consist of consumer spending and business investment (AE = C + I). Panel A shows AE and its relationship with income (Y); when spending equals income, the economy is on the Y = AE line. Panel B shows the corresponding saving and investment schedules. Point a in both panels shows where income equals consumption and saving is zero. Therefore, saving is positive for income levels above $4,000 and negative at incomes below $4,000. The vertical distance ef in panel A represents investment ($100); it is equal to I0 in panel B. Equilibrium income and output is $4,400 (point e), because this is the level at which businesses are producing just what other businesses and consumers want to buy.

Once the economy has moved to $4,400, what consumers and businesses want to buy is exactly equal to the income and output being produced. Businesses are producing $4,400, aggregate expenditures are equal to $4,400, and there are no pressures on the economy to move away from point e. Income of $4,400, or point e, is an equilibrium point for the economy.

Panel B shows this same equilibrium, again as point e. Is it a coincidence that saving and investment are equal at this point where income and output are at equilibrium? The answer is no. In this simple private sector model, saving and investment will always be equal when the economy is in equilibrium.

Remember that aggregate expenditures are equal to consumption plus business investment (AE = C + I). Recall also that at equilibrium, aggregate expenditures, income, and output are all equal; what is demanded is supplied (AE = Y). Finally, keep in mind that income can either be spent or saved (Y = C + S). By substitution, we know that, at equilibrium,

AE = Y = C + I

We also know that

Y = C + S

Substituting C + I for Y yields

C + I = C + S

Canceling the C’s, we find that, at equilibrium,

I = S

Thus, the location of point e in panel B is not just coincidental; at equilibrium, actual saving and investment are always equal. Note that at point a, saving is zero, yet investment spending is $100 at I0. This difference means businesses desire to invest more than people desire to save. With desired investment exceeding desired saving, this cannot be an equilibrium point, because saving and investment must be equal in order for the economy to be at equilibrium. Indeed, income will rise until these two values are equal at point e.

injections Increments of spending, including investment, government spending, and exports.

withdrawals Activities that remove spending from the economy, including saving, taxes, and imports.

What is important to take from this discussion? First, when intended (or desired) saving and investment differ, the economy will have to grow or shrink to achieve equilibrium. When desired saving exceeds desired investment—at income levels above $4,400 in panel B—income will decline. When intended saving is below intended investment—at income levels below $4,400—income will rise. Notice that we are using the words “intended” and “desired” interchangeably.

Second, at equilibrium all injections of spending (investment in this case) into the economy must equal all withdrawals (saving in this simple model). Spending injections increase aggregate income, while spending withdrawals reduce it. This fact will become important as we add government and the foreign sector to the model.

The Multiplier Effect Given an initial investment of $100 (I0), equilibrium is at an output of $4,400 (point e). Remember that at equilibrium, what people withdraw from the economy (saving) is equal to what others are willing to inject into the spending system (investment). In this case both values equal $100. Point e is an equilibrium point because there are no pressures in the system to increase or decrease output; the spending desires of consumers and businesses are satisfied.

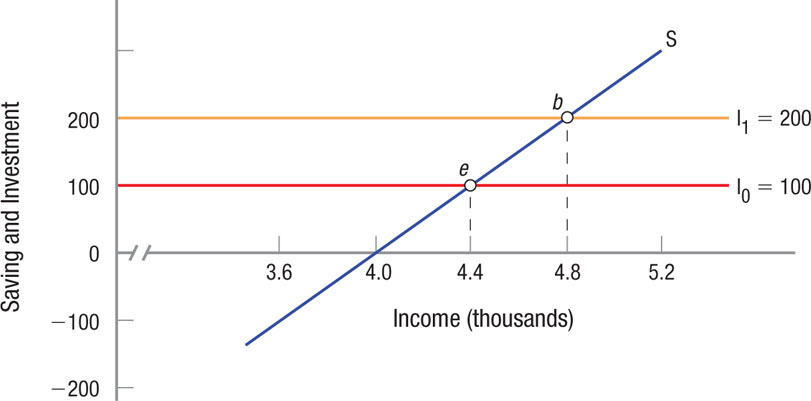

The Multiplier Let us assume full employment occurs at output $4,800. How much would investment have to increase to move the economy out to full employment? As Figure 6 shows, investment must rise to $200 (I1), an increase of $100. With this new investment, equilibrium output moves from point e to point b, and income rises from $4,400 to $4,800.

FIGURE 6

Saving and Investment When investment is $100, equilibrium employment occurs at an output of $4,400 (point e). When investment rises to $200 (I1), equilibrium output climbs to $4,800 (point b). Thus, $100 of added investment spending causes income to grow by $400. This is the multiplier at work.

multiplier Spending changes alter equilibrium income by the spending change times the multiplier. One person’s spending becomes another’s income, and that second person spends some (the MPC), which becomes income for another person, and so on, until income has changed by 1/(1 − MPC) = 1/MPS. The multiplier operates in both directions.

What is remarkable here is that a mere $100 of added spending (investment in this case) caused income to grow by $400. This phenomenon is known as the multiplier effect. Recognizing it was one of Keynes’s major insights. How does it work?

JOHN MAYNARD KEYNES (1883–1946)

In 1935, John Maynard Keynes boasted in a letter to playwright George Bernard Shaw of a book he was writing that would revolutionize “the way the world thinks about economic problems.” This was a brash prediction to make, even to a friend, but it was not an idle boast. His General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money did change the way the world looked at economics.

Keynes belongs to a small class of economic earth-shakers which includes Karl Marx and Adam Smith. His one-man war on classical theory launched a new field of study known as macroeconomics. His ideas would have a profound influence on theorists and government policies for decades to come.

Keynes was once asked if there was any era comparable to the Great Depression. He replied, “It was called the Dark Ages and it lasted 400 years.” His prescription to President Franklin D. Roosevelt was to increase government spending to stimulate the economy. Sundeep Reddy reports that “during a 1934 dinner…after one economist carefully removed a towel from a stack to dry his hands, Mr. Keynes swept the whole pile of towels on the floor and crumpled them up, explaining that his way of using towels did more to stimulate employment among restaurant workers” (The Wall Street Journal, January 8, 2009, p. A10).

During the world economic depression in the early 1930s, Keynes became alarmed when unemployment in England continued to rise after the first few years of the crisis. Keynes argued that aggregate expenditures, the sum of consumption, investment, government spending, and net exports, determined the levels of economic output and employment. When aggregate expenditures were high, the economy would foster business expansion, higher incomes, and high levels of employment. With low aggregate spending, businesses would be unable to sell their inventories and would cut back on investment and production.

The ideas formulated by Keynes dramatically changed the way government policy is used throughout the world. Today, as many countries face a slow economic recovery, governments have taken a more proactive role in their economies in hopes of avoiding another downturn of the magnitude seen in the 1930s.

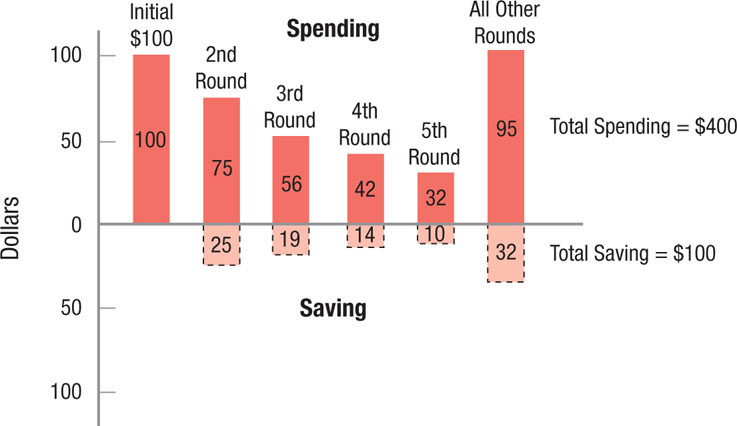

In this example, we have assumed the marginal propensity to consume is 0.75. Therefore, for each added dollar received by consumers, $0.75 is spent and $0.25 is saved. Thus, when businesses invest an additional $100, the firms providing the machinery will spend $75 of this new income on more raw materials, while saving the remaining $25. The firms supplying the new raw materials have $75 of new income. These firms will spend $56.25 of this (0.75 × $75.00), while saving $18.75 ($56.25 + $18.75 = $75.00). This effect continues on until the added spending has been exhausted. As a result, income will increase by $100 + $75 + $56.25…. In the end, income rises by $400. Figure 7 outlines this multiplier process.

FIGURE 7

The Multiplier Process An initial $100 of spending generates more spending because of the multiplier process shown in this figure. With an MPC = 0.75 in the second round, $75 is spent and $25 is saved. In the third round, $56.25 of the previous $75 is spent and $18.75 is saved, and so on. Total spending is $400, and total saving is $100 when all rounds are completed.

The general formula for the spending multiplier (k) is

k = 1/(1 − MPC)

Alternatively, because MPC + MPS = 1, the MPS = 1 − MPC, therefore

k = 1/MPS

Thus, in our simple model, the multiplier is

1/(1 − 0.75) = 1/0.25 = 4

As a result of the multiplier effect, new spending will raise equilibrium by 4 times the amount of new spending. Note that any change in spending (consumption, investment—and as we will see in the next section—government spending or changes in net exports) will also have this effect. Spending is spending. Note also—and this is important—the multiplier works in both directions.

The Multiplier Works in Both Directions

If spending increases raise equilibrium income by the increase times the multiplier, a spending decrease will reduce income in corresponding fashion. In our simple economy, for instance, a $100 decline in investment or consumer spending will reduce income by $400.

This is one reason why recession watchers are always concerned about consumer confidence. During a recession, income declines, or at least the rate of income growth falls. If consumers decide to increase their saving to guard against the possibility of job loss, they may inadvertently make the recession worse. As they pull more of their money out of the spending stream, withdrawals increase, and income is reduced by a multiplied amount as other agents in the economy feel the effects of this reduced spending. The result can be a more severe or longer lasting recession.

paradox of thrift When investment is positively related to income and households intend to save more, they reduce consumption, income, and output, reducing investment so that the result is that consumers actually end up saving less.

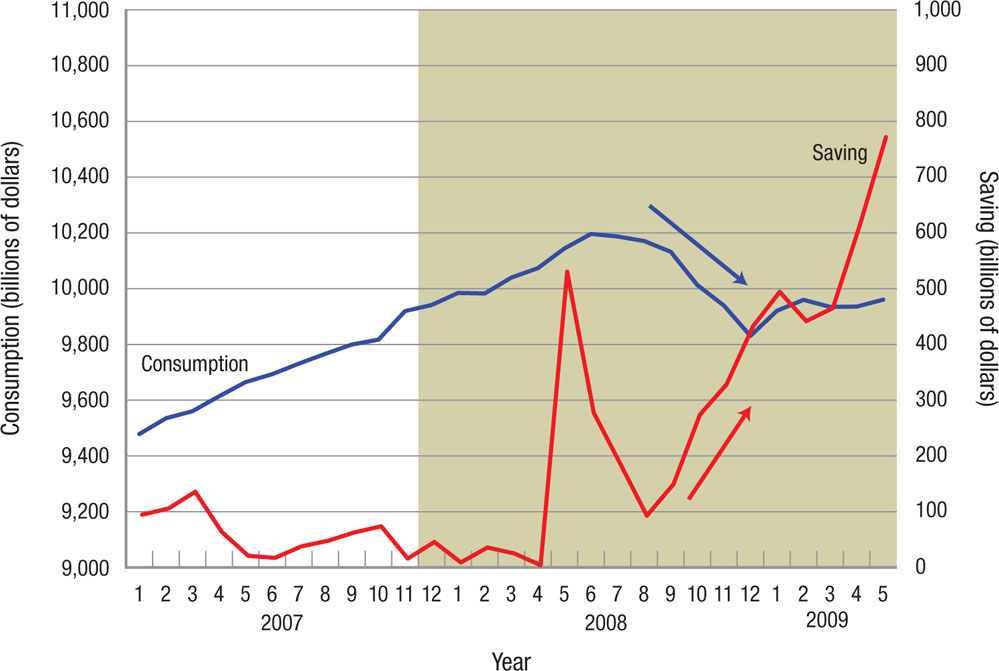

This was the case when consumer spending peaked in the summer of 2008. After that, auto sales plummeted and housing prices and sales fell. As the recession that started in December 2007 progressed and jobs were lost, consumers reduced their spending. As their confidence in the economy evaporated, households began to save more, consumer spending declined further, and the economy sunk into a deeper recession. Figure 8 shows how consumer spending (downward arrow) fell and saving rose (upward arrow) after September 2008. Leading up to the recession, saving was less than 1% of personal income, but by mid-2009 it had grown to 7%. Before the recession, aggregate household debt had soared, and part of what we are seeing in Figure 8 may reflect households spending less in order to pay off debt and return to more sustainable levels of debt.

Paradox of Thrift The implication of Keynesian analysis for actual aggregate household saving and household intentions regarding saving is called the paradox of thrift. As we saw in Figure 8, if households intend (or desire) to save more, they will reduce consumption, thereby reducing income and output, resulting in job losses and further reductions in income, consumption, business investment, and so on. The end result is an aggregate equilibrium with lower output, income, investment, and in the end, lower actual aggregate saving.

FIGURE 8

Consumption and Saving, 2007–2009 Consumption declined as the recession developed, and consumer worries about job losses and the decline in housing prices resulted in households saving more. The shaded area on the right represents the recession.

Do High Savings Rates Increase the Risk of a Long Recession?

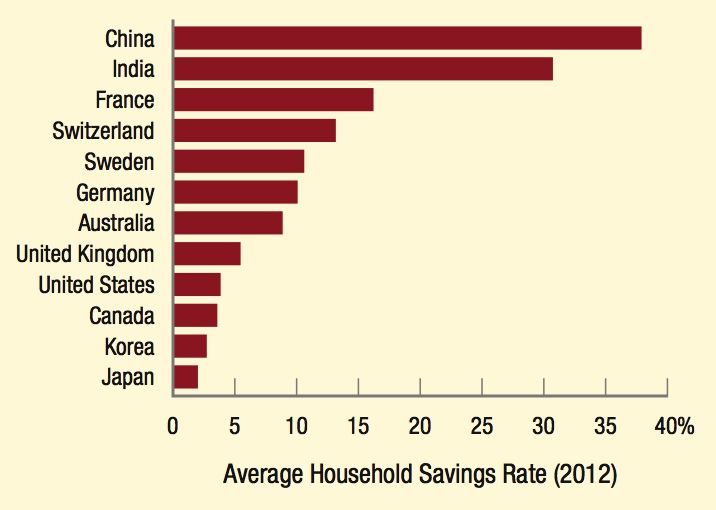

Everyone has a frugal friend or relative who saves every penny possible, or a shopaholic friend who can’t seem to save any money at all. These differences in savings rates often are influenced by economic and demographic factors.

People with higher incomes tend to save a larger portion of their incomes than those with lower incomes. Older people tend to save more than younger people. And those living in rural areas tend to save more than those in urban areas. Yet, although these factors explain savings rates within a country, they do not fully explain the savings rate across countries. In other words, cultural differences play an important role as well.

The following table shows the average household saving rate in a sample of twelve countries in 2012. China and India rank at the top of this list, despite having a lower income per capita than any other country on the list. The United States, which has the highest income per capita among the countries shown, has a savings rate toward the bottom. And some countries have seen dramatic changes in their savings rate, such as Japan, which had one of the highest savings rates 30 years ago but today has the lowest savings rate among the countries shown.

The savings rate plays an important role in an economy. A high savings rate, such as that in China, India, and France, gives a country’s banking system a vote of confidence; people trust putting their money into financial institutions and expect the money will be available when desired. Also, savings provide opportunities for others to borrow, providing inexpensive access to loans for investment.

However, a high savings rate can also make a country vulnerable in times of recession. The adverse effects of a high savings rate occurred in Japan in the 1990s. Facing a difficult recession, a high savings rate prevented government incentives to jumpstart consumption and investment from being effective. In other words, the multiplier was too low to pull the economy out of recession, resulting in a decadelong recession referred to as the Lost Decade.

Today, Japan’s savings rate is among the lowest in the world, as income growth stalled and consumerism rose. Yet, a greater willingness to spend portends well in terms of its ability to recover from the next recession. On the other hand, China and India, which have enjoyed high growth rates and high savings rates, may one day face an enduring recession if their dynamic growth machines eventually sputter.

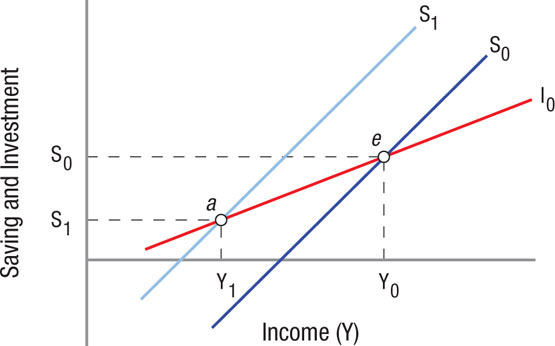

Notice that we have modified our assumption about investment—it now varies with economic conditions and is positively related to income. When the economy improves and income (or output) rises, investment expands as well, and vice versa when the economy sours. This is shown in our simple aggregate expenditures framework in Figure 9.

FIGURE 9

Paradox of Thrift When consumers intend to save more and consume less (the saving schedule shifts from S0 to S1), and if investment is a rising function of income, the end result is that at equilibrium, households actually end up saving less (point a).

Initially the economy is in equilibrium at point e with saving equal to S0. If households desire to save more because they feel insecure about their jobs, the savings curve will shift to the left to S1. Now at all levels of income households intend to save more. This sets up the chain reaction described above, leading to a new equilibrium at point a, where equilibrium income has fallen to Y1 and actual saving has declined to S1. The paradox is that if everyone tries to save more (even for good reasons), in the aggregate they may just save less.

THE SIMPLE AGGREGATE EXPENDITURES MODEL

- Ignoring both government and the foreign sector in a simple aggregate expenditures model, macroeconomic equilibrium occurs when aggregate expenditures are just equal to what is being produced.

- At equilibrium, aggregate saving equals aggregate investment.

- The multiplier process amplifies new spending because some of the new spending is saved and some becomes additional spending. And some of that spending is saved and some is spent, and so on.

- The multiplier is equal to 1/(1 − MPC) = 1/MPS.

- The multiplier works in both directions. Changes in spending are amplified, changing income by more than the initial change in spending.

- The paradox of thrift results when households intend to save more, but at equilibrium they end up saving less.

QUESTION: Business journalists, pundits, economists, and policymakers all pay attention to the results of the Conference Board’s monthly survey of 5,000 households, called the Consumer Confidence Index. When the index is rising, this is good news for the economy, and when it is falling, concerns are often heard that it portends a recession. Why is this survey important as a tool in forecasting where the economy is headed in the near future?

When consumer confidence is declining, this may suggest that consumers are going to spend less and save more. Because consumer spending is roughly 70% of aggregate spending, a small decline represents a significant reduction in aggregate spending and may well mean that a recession is on the horizon. Relatively small changes in consumer spending coupled with the multiplier can mean relatively large changes in income, and therefore forecasters and policymakers should keep a close eye on consumer confidence.