Financing the Federal Government

In the late 1990s, some economists argued that spending should be reduced, taxes increased, or a contractionary monetary policy implemented to cool down an economy and stock market that were overheating. Their advice was partly heeded, in that tax rates were increased as the economy entered a boom, and the federal budget ended the 1990s in surplus. The recession of 2001, caused in part by the fall in the stock market and a reduction in investment, moved the budget back into deficit. Let’s first define deficits, surpluses, and public debt before studying their impact on the economy.

Defining Deficits and the National Debt

deficit The amount by which annual government spending exceeds tax revenues.

surplus The amount by which annual tax revenues exceed government expenditures.

A deficit is the amount by which annual government spending exceeds tax revenues. A surplus is the amount by which annual tax revenues exceed government expenditures. In 2000, the budget surplus was $236.2 billion. By 2002, tax cuts, a recession, and new commitments for national defense and homeland security had turned the budget surpluses of 1998–2001 into deficits—a deficit of $157.8 billion for fiscal year 2002. The effects of the deep recession in 2007–2009, and the extent of fiscal policies used, changed the magnitude of the deficit picture again. Government intervention and support for the financial and automobile industries and a nearly $800 billion stimulus package to soften the recession resulted in a 2009 deficit of over $1.4 trillion. However, the economic recovery since 2009 has reduced the deficit from its peak.

public debt The total accumulation of past deficits and surpluses; it includes Treasury bills, notes, and bonds, and U.S. Savings Bonds.

The public debt, or national debt, is the total accumulation of past deficits less surpluses. Gross public debt in 2013 was over $16 trillion, but public debt held by the public was only three-quarters of that amount (about $12 trillion). Some agencies of government, such as the Social Security Administration, the Treasury Department, and the Federal Reserve, hold some debt; one agency of government owes money to another. Debt held by the public (including foreign governments) is debt that represents a claim on government assets, not simply intergovernmental transfers.

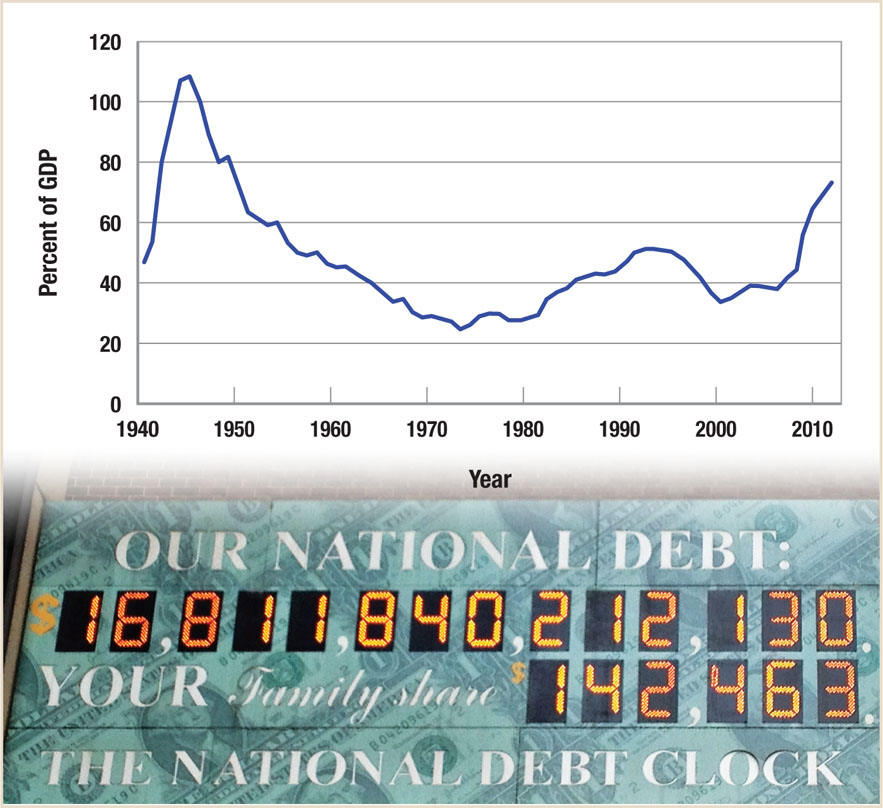

Figure 8 shows the public debt held by the public as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) since 1940. During World War II, public debt exceeded GDP. It then trended downward until the early 1980s, when public debt began to climb again. Public debt held by the public as a percentage of GDP fell from the mid-1990s until 2000, first because of growing budget surpluses in the late 1990s, then because of falling interest rates (what the government has to pay on the debt), but it has risen since then. Public debt held by the public (as opposed to government institutions) has surpassed 70% of GDP.

FIGURE 8

Public Debt Held by the Public as a Percent of GDP The public debt as a percentage of GDP has varied considerably since 1940. During World War II, public debt exceeded GDP. It then trended downward until the early 1980s, when public debt began to climb again. In 2012, public debt held by the public (as opposed to government institutions) exceeded 70% of GDP.

How Big Is the Economic Burden of Interest Rates on the National Debt?

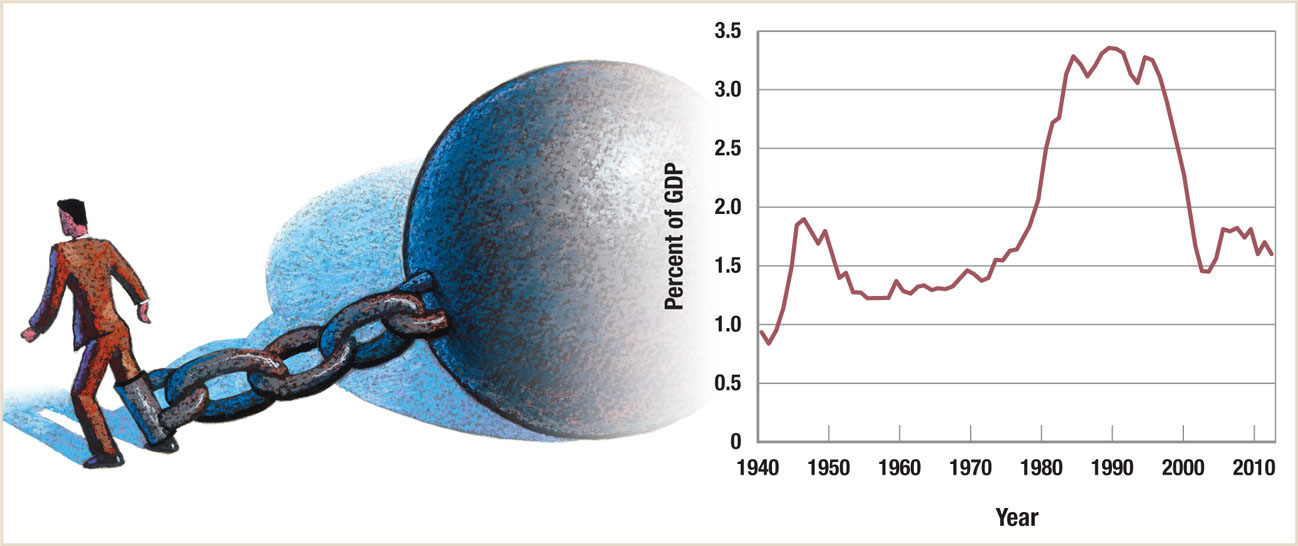

The federal government paid almost $250 billion in interest payments on the national debt in 2012. This is money that could have been used for other public programs. In fact, interest payments on the debt were greater than the amount the government paid for education, transportation infrastructure, low-income housing, and Homeland Security combined.

Although interest payments on the debt are large, they represent a small portion of the federal budget and an even smaller portion of GDP. Interest on the debt as a percentage of GDP, as shown in the figure, was steady from 1950 to 1980, hovering around 1.5%. This percentage more than doubled during the 1980s because of high inflation and interest rates, and rising deficits. In the mid-1990s, interest rates dropped and deficits fell, even becoming surpluses for a short time. Consequently, interest as a percentage of GDP dropped toward the level it was in the 1950s. To day, budget deficits are again rising, but with interest rates at record lows, interest payments remain a small percentage of GDP.

The fact that rising debt has not led to dramatic borrowing costs highlights the important role that interest rates have on the economy. Many individuals, firms, and foreign governments hold long-term (up to 30-year) Treasury bonds, During the economic crisis in the early 1980s, interest rates on 30-year Treasury bonds reached 15%, guaranteeing a bondholder a 15% annual return for 30 years.

Today, those 15% bonds from the 1980s are maturing, and new 30-year bonds are paying less than 4%, resulting in tremendous savings to the government in financing the national debt. For example, an average interest rate of 2% saves the U.S. federal government $500 billion per year compared to a 5% interest rate, and saves over $1 trillion per year compared to an 8% interest rate.

Why have long-term interest rates remained low despite the high debt and a debt downgrade in U.S. bonds? One reason is that volatility in stock markets makes U.S. debt still one of the safest investments in the world. Second, foreign governments perceive the U.S. dollar as a valuable hard currency, and thus buy our bonds as a way to build up their national reserves. For these reasons and more, the U.S. government has little trouble selling bonds at low interest rates.

Despite the current favorable conditions under which the U.S. government finances its debt, it must still focus on keeping debt in check for a number of reasons. First, interest payments on external (foreign) holdings of U.S. debt are a leakage from our economy. Second, bond prices can change quickly, increasing the burden of the debt. Third, as interest rates rise in the future, low interest rate bonds issued today will mature and may be replaced by higher interest rate bonds.

Public debt is held as U.S. Treasury securities, including Treasury bills, notes, bonds, and U.S. Savings Bonds. Treasury bills, or T-bills, as they are known, are short-term instruments with a maturity period of a year or less that pay a specific sum at maturity. T-bills do not pay interest. Rather, they are initially sold at a discount, and their yields are then determined by the time to maturity and the discount. T-bills are the most actively traded securities in the U.S. economy, and they are highly liquid, providing the closest thing there is to risk-free returns.

Treasury notes are financial instruments issued for periods ranging from 1 to 10 years, whereas Treasury bonds have maturity periods exceeding 10 years. Both of these instruments have stated interest rates and are traded sometimes at discounts and sometimes at premiums.

Today, interest rates on the public debt are between 1% and 4%. This relatively low rate has not always been the case. In the early 1980s, interest rates varied from 11% to nearly 15%. Inflation was high and investors required high interest rates as compensation. When rates are high, government interest costs on the debt soar.

Balanced Budget Amendments

Although federal budget deficits have been the norm for the past 50 years, the recent severe recession led to record deficits, leading many politicians to propose federal balanced budget amendments requiring the federal government to balance its budget every year. Balanced budget amendments are not new. They exist for most state governments. At the federal level, however, such rules have not existed since the 1930s.

annually balanced budget Federal expenditures and taxes would have to be equal each year.

Most balanced budget amendments require an annually balanced budget, which means government would have to equate its revenues and expenditures every year. Most economists, however, believe such rules are counterproductive. For example, during times of recession, tax revenues tend to fall due to lower incomes and higher unemployment. To offset these lost revenues, an annually balanced budget would require deep spending cuts or tax hikes (in other words, contractionary policy) during a time when expansionary policies are needed. Many economists believe that balanced budget rules of the early 1930s turned what probably would have been a modest recession into the global Depression.

cyclically balanced budget Balancing the budget over the course of the business cycle by restricting spending or raising taxes when the economy is booming and using these surpluses to offset the deficits that occur during recessions.

An alternative to balancing the budget annually would be to require a cyclically balanced budget, in which the budget is balanced over the course of the business cycle. The basic idea is to restrict spending or raise taxes when the economy is booming, allowing for a budget surplus. These surpluses would then be used to offset deficits accrued during recessions, when increased spending or lower taxes are appropriate. To some extent, balancing the budget over the business cycle happens automatically as long as fiscal policy is held constant due to the automatic stabilizers discussed earlier. However, the business cycle takes time to define (due to lags), making it difficult to enforce such a rule in practice.

functional finance Essentially ignores the impact of the budget on the business cycle and focuses on fostering economic growth and stable prices, while keeping the economy as close as possible to full employment.

Finally, some economists believe that balancing the budget should not be the primary concern of policymakers; instead, they view the government’s primary macroeconomic responsibility to foster economic growth and stable prices, while keeping the economy as close as possible to full employment. This is the functional finance approach to the federal budget, where governments provide public goods and services that citizens want (such as national defense, education, etc.) and focus on policies that keep the economy growing, because rapidly growing economies do not have significant public debt or deficit issues.

In sum, balancing the budget annually or over the business cycle may be either counterproductive or difficult to do. It is not a solution to the public choice problem we discussed above of politicians’ incentives to spend and not raise taxes. Budget deficits begin to look like a normal occurrence in our political system.

Financing Debt and Deficits

Seeing as how deficits may be persistent, how does the government deal with its debt, and what does this imply for the economy? Government deals with debt in two ways. It can either borrow or sell assets.

Given its power to print money and collect taxes, the federal government cannot go bankrupt per se. But it does face what economists call a government budget constraint:

government budget constraint The government budget is limited by the fact that G − T = ΔM + ΔB + ΔA.

G − T = ΔM + ΔB + ΔA

where

G = government spending

T = tax revenues, thus (G − T) is the federal budget deficit

ΔM = the change in the money supply (selling bonds to the Federal Reserve)

ΔB = the change in bonds held by public entities, domestic and foreign

ΔA = the sales of government assets

The left side of the equation, G − T, represents government spending minus tax revenues. A positive (G − T) value is a budget deficit, and a negative (G − T) value represents a budget surplus. The right side of the equation shows how government finances its deficit. It can sell bonds to the Federal Reserve, sell bonds to the public, or sell assets. Let’s look at each of these options.

- ΔM > 0: First, the government can sell bonds to government agencies, especially the Federal Reserve, which we will study in depth in a later chapter. When the Federal Reserve buys bonds, it uses money that is created out of thin air by its power to “print” money. When the Federal Reserve pumps new money into the money supply to finance the government’s debt, it is called monetizing the debt.

- ΔB > 0: If the Federal Reserve does not purchase the bonds, they may be sold to the public, including corporations, banks, mutual funds, individuals, and foreign entities. This also has the effect of financing the government’s deficit.

- ΔA > 0: Asset sales represent only a small fraction of government finance in the United States. These sales include auctions of telecommunications spectra and offshore oil leases. Developing nations have used asset sales, or privatization, in recent years to bolster sagging government revenues and to encourage efficiency and development in the case where a government-owned industry is sold.

Thus, when the government runs a deficit, it must borrow funds from somewhere, assuming it does not sell assets. If the government borrows from the public, the quantity of publicly held bonds will rise; if it borrows from the Federal Reserve, the quantity of money in circulation will rise.

The main idea from this section is that deficits must be financed in some form, whether by the government borrowing or selling assets, or paid for by a combination of rising private savings and falling investment. As we’ll see in the next section, rising levels of deficits and the corresponding interest rates raise some important issues about the ability of a country to manage its debt burden.

FINANCING THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT

- A deficit is the amount that government spending exceeds tax revenue in a particular year.

- The public (national) debt is the total accumulation of past deficits less surpluses.

- Approaches to financing the federal government include annually balancing the budget, balancing the budget over the business cycle, and ignoring the budget deficit and focusing on promoting full employment and stable prices.

- The federal government’s debt must be financed by selling bonds to the Federal Reserve (“printing money” or “monetizing the debt”), by selling bonds to the public, or by selling government assets. This is known as the government budget constraint.

QUESTION: One reason why state governments have been more willing to pass balanced budget amendments than the federal government is the difference between mandatory and discretionary spending. What are some expenses of the federal government that are less predictable or harder to cut that make balanced budget amendments more difficult to pursue?

The federal government must satisfy its mandatory spending requirements, including Social Security, unless it passes a law to reform such spending. Also, the federal government must pay for national defense, including wars, which are unpredictable. Also unpredictable are expenses related to natural disasters, which require action by various federal agencies. Because of the combination of various mandatory spending programs and unpredictable discretionary spending requirements, the federal government would find it difficult in practice to enforce a balanced budget amendment.