What Is Money?

Anything can serve as money, from the cowrie shells of the Maldives to the huge stone disks used on the Pacific islands of Yap. And now, it seems, in this electronic age nothing can serve as money too.

Money is anything that is accepted in exchange for goods and services or for the payments of debts.

Niall Ferguson, The Ascent Of Money

Money is anything that is accepted in exchange for goods and services or for the payment of debt. We are familiar with currency and coins; we use them nearly every day. Over the ages, however, a wide variety of commodities have served as money—giant circular stones on the island of Yap, wampum (trinkets) among early Native Americans, and cigarettes in prisoner-of-war camps during World War II.

fiat money Money without intrinsic value but nonetheless accepted as money because the government has decreed it to be money.

First, for a commodity to be used as money, its value must be easy to determine. Therefore, it must be easily standardized. Second, it must be divisible, so that people can make change. Third, money must be durable and portable. It must be easy to carry (so much for the giant circular stones, which today are used only for ceremonial purposes in Yap.) Fourth, a commodity must be accepted by many people as money if it is to act as money. As Niall Ferguson makes clear in the quote above, today we have “virtual” money, in the sense that digital money is moved from our employer to the bank and then to the retailer for our goods and services in nothing but a series of electronic transactions. This is really the ultimate in fiat money: money without any intrinsic value but accepted as money because the government has made it legal tender.

Money is so important that nearly every society has invented some form of money for its use. We begin our examination of money by looking at its functions.

The Functions of Money

Money has three primary functions in our economic system: as a medium of exchange, as a measure of value (unit of account), and as a store of value. These uses make money unique among commodities.

barter The direct exchange of goods and services for other goods and services.

Medium of Exchange Let us start with a primitive economy. There is no money. To survive, you have to produce everything yourself: food, clothing, housing. It is a fact that few of us can do all of these tasks equally well. Each one of us is better off specializing, providing those goods and services we are more efficient at supplying. Say I specialize in dairy products and you specialize in blacksmithing. We can engage in barter, which is the direct exchange of goods and services. I can give you gallons of milk if you make me a pot for cooking. A double coincidence of wants occurs if, in a barter economy, I find someone who not only has something I want, but who also wants something I have. What happens if you, the blacksmith, are willing to make the cooking pot for me but want clothing in return? Then I have to search out someone who is willing to give me clothing in exchange for milk; I will then give you the clothing in exchange for the cooking pot. You can see that this system quickly becomes complicated. This is why barter is restricted to primitive economies.

medium of exchange Money is a medium of exchange because goods and services are sold for money, then the money is used to purchase other goods and services.

Consider what happens when money is introduced. Everyone can spend their time producing goods and services, rather than running around trying to match up exchanges. Everyone can sell their products for money, and then can use this money to buy cooking pots, clothing, or whatever else they want. Thus, money’s first and most important function is as a medium of exchange. Without money, economies remain primitive.

Unit of Account Imagine the difficulties consumers would have in a barter economy in which every item is valued in terms of the other products offered—12 eggs are worth 1 shirt, 1 shirt equals 3 gallons of gas, and so forth. A 10-product economy of this sort, assigning every product a value for every other product, would require 45 different prices. A 100-good economy would require 4,950 prices.1 This is another reason why only the most primitive economies use barter.

unit of account Money provides a yardstick for measuring and comparing the values of a wide variety of goods and services. It eliminates the problem of double coincidence of wants associated with barter.

Once again, money is able to solve a problem inherent to the barter economy. It reduces the number of prices consumers need to know to the number of products on the market; a 100-good economy will have 100 prices. Thus, money is a unit of account, or a measure of value. Dollar prices give us a yardstick for measuring and comparing the values of a wide variety of goods and services.

Admittedly, ascribing a dollar value to some things, such as human life, love, and clean air, can be difficult. Still, courts, businesses, and government agencies manage to do so every day. For example, if someone dies and the court determines this death was due to negligence, the court tries to determine the value of the life to the person’s survivors—not a pleasant task, but one that has to be undertaken. Without a monetary standard, such valuations would be not just difficult, but impossible.

store of value The function that enables people to save the money they earn today and use it to buy the goods and services they want tomorrow.

Store of Value Using cherry tomatoes as a medium of exchange and unit of account might be handy, except that they have the bad habit of rotting. Money lasts, enabling people to save the money they earn today and use it to buy the goods and services they want tomorrow. Thus, money is a store of value. It is true that money is not unique in preserving its value. Many other commodities, including stocks, bonds, real estate, art, and jewelry are used to store wealth for future purchases. Indeed, some of these assets may rise in value, and therefore might be preferred to money as a store of value. Why, then, use money as a store of wealth at all?

The answer is that every other type of asset must be converted into money if it is to be spent or used to pay debts. Converting other assets into cash involves transaction costs, and for some assets, these costs are significant. An asset’s liquidity is determined by how fast, easily, and reliably it can be converted into cash.

liquidity How quickly, easily, and reliably an asset can be converted into cash.

Money is the most liquid asset because, as the medium of exchange, it requires no conversion. Stocks and bonds are also liquid, but they do require some time and often a commission fee to convert into cash. Prices in stock and bond markets fluctuate, causing the real value of these assets to be uncertain. Real estate requires considerable time to liquidate, with transaction costs that often approach 10% of a property’s value.

Money differs from many other commodities in that its value does not deteriorate in the absence of inflation. When price levels do rise, however, the value of money falls: If prices double, the value of money is cut in half. In times of inflation, most people are unwilling to hold much of their wealth in money. If hyperinflation hits, money will quickly become worthless as the economy reverts to barter.

Money, then, is crucial for a well-functioning modern economy. All of its three primary functions are important: medium of exchange, unit of account, and store of value.

Defining the Money Supply

How much money is there in the U.S. economy? One of the tasks assigned to the Federal Reserve System (the Fed), the central bank of the United States, is that of measuring our money supply. The Fed has developed several different measures of monetary aggregates, which it continually updates to reflect the innovative new financial instruments our financial system is constantly developing. The monetary aggregates the Fed uses most frequently are M1, the narrowest measure of money, and M2, a broader measure. An even broader measure called M3 was published until 2006 when the Fed decided the additional benefit of this measure was not worth the costs of collecting the data.

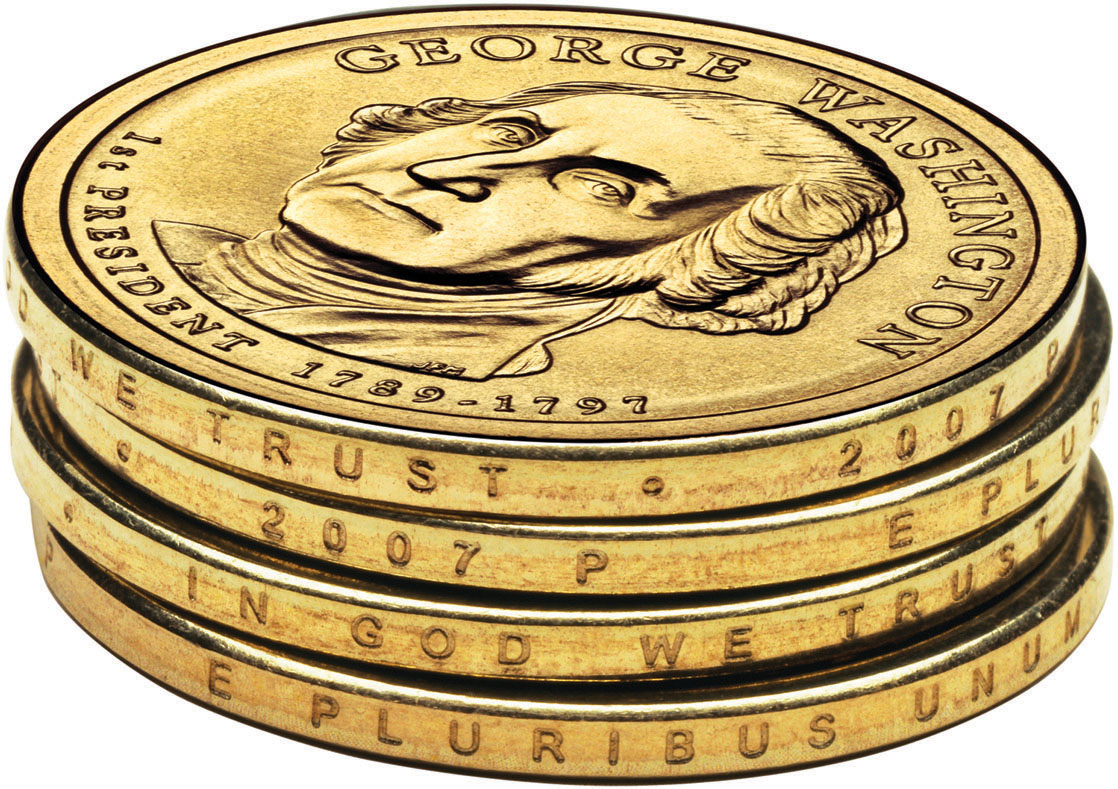

Where Did All the Dollar Coins Go?

When is the last time you received a presidential, Sacagawea, or Susan B. Anthony dollar as change for some purchase you made? For most of us, the answer approaches never. Why don’t dollar coins circulate in the United States?

The benefits of a dollar coin are clear: Coins last much longer than dollar bills, which tend to deteriorate within 18 months. Annual savings from minting coins over printing dollar bills runs to $500 million a year, because although production costs are higher, coins circulate longer than bills, making total costs lower for coins. This is why the U.S. Treasury has tried twice recently to introduce dollar coins.

Introducing dollar coins faces several serious hurdles. First, several industries will incur added costs. For example, banks will have additional costs to sort, store, and wrap the coins, and vending machines must be altered to accept the coins. The coins cannot be too big, or the public will reject them as being too heavy; this was the problem with the Kennedy half-dollar and the silver dollars of the past. But a small dollar, roughly the size of a quarter, generates confusion—Is it a dollar or a quarter?—and again has been rejected by the public.

Other countries have successfully introduced dollar coins: Canada has $1 and $2 coins and Britain has £1 and £2 coins. All are circulated widely. What do we need to do to launch a successful dollar coin in the United States?

After reviewing the experiences of other countries, the General Accounting Office (GAO) concluded that a successful introduction of a dollar coin would require that the government develop a substantial awareness campaign (a heavy, extended advertising campaign) to overcome initial public resistance. Second, the Treasury must mint sufficient coins for acceptance by the public. Third, and probably most important, the dollar bill would have to be eliminated. A key element in the general acceptance of the dollar coins in Canada was that the populace had no choice: The dollar bill was removed from circulation at the same time the dollar coin was introduced.

This being the case, why did the U.S. Treasury try once again in 2007 to launch a dollar coin without removing the paper dollar from circulation? These new coins were based on the popularity of the state quarters program, through which each year five state quarters were released into general circulation. The new dollar coins released in 2007 were engraved with an image of George Washington, and eventually over the years all of the presidents would be represented. But despite the government’s efforts to market the new coins, the public again shunned their use, forcing the government to store millions of uncirculated dollar coins in vaults. In December 2011, the government suspended their production, announcing that only a limited number of each presidential dollar coin would be produced to satisfy the demand from coin collectors.

Given the potential annual savings, we will undoubtedly see further attempts at introducing a dollar coin in the United States. But until the idea of using dollar coins is accepted by most Americans, the U.S. paper dollar will continue to reign supreme.

More specifically, the Fed defines M1 and M2 as follows:

M1 equals:

• Currency (banknotes and coins)

+ Traveler’s checks

+ Demand deposits

+ Other checkable deposits

M2 equals:

• M1

+ Savings deposits

+ Money market deposit accounts

+ Small-denomination (less than $100,000) time deposits

+ Shares in retail money market mutual funds

M1 The narrowest definition of money; includes currency (coins and paper money), traveler’s checks, demand deposits (checks), and other accounts that have check-writing or debit capabilities. The most liquid instruments that might serve as money.

Narrowly Defined Money: M1 Because money is used mainly as a medium of exchange, when defined most narrowly it includes currency (banknotes and coins), demand deposits (checking accounts), and other accounts that have check-writing capabilities. Currency represents slightly less than half of M1, with banknotes constituting more than 90% of currency; coins form only a small part of M1. Checking accounts represent the other half of the money supply, narrowly defined. Currently, M1 is equal to roughly $2.5 trillion. It is the most liquid part of the money supply.

Checking accounts can be opened at commercial banks and at a variety of other financial institutions, including credit unions, mutual savings banks, and savings and loan associations. Also, many stock brokerage firms offer checking services on brokerage accounts.

M2 A broader definition of money that includes “near monies” that are not as liquid as cash, including deposits in savings accounts, money market accounts, and money market mutual fund accounts.

A Broader Definition: M2 A broader definition of money, M2, includes the “near monies”: money that cannot be drawn on instantaneously but that is nonetheless accessible. This includes deposits in savings accounts, money market deposit accounts, and money market mutual fund accounts. Many of these accounts have check-writing features similar to demand deposits.

Certificates of deposit (CDs) and other small-denomination time deposits can usually be cashed in at any time, although they often carry penalties for early liquidation. Thus, M2 includes the highly liquid assets in M1 and a variety of accounts that are less liquid, but still easy and inexpensive to access. This broader definition of money brings the current money supply up to over $10 trillion.

When economists speak of “the money supply,” they are usually referring to M1, the narrowest definition. Even so, the other measures are sometimes used. The index of leading economic indicators, for instance, uses M2, adjusted for inflation, to gauge the state of the economy. Economists sometimes disagree on which is the better measure of the money supply; although M1 and M2 tend to have similar trends, they have deviated significantly in certain periods. For the remainder of this book, the money supply will be considered to be M1 unless otherwise specified.

The monetary components that make up the money supply serve many purposes. But at its essence, it channels funds from savers to borrowers, an important function of the financial system that barter societies are unable to do. In the next section, we look at a simple model of loanable funds to show how savers and borrowers come together to make moneylending possible and contribute to economic growth.

WHAT IS MONEY?

- Money is anything accepted in exchange for goods and services and for the payment of debts.

- The functions of money include: a medium of exchange, a unit of account, and a store of value.

- Liquidity refers to how fast, easily, and reliably an asset can be converted into cash.

- M1 is currency plus demand deposits plus other checkable deposits.

- M2 is equal to M1 plus savings deposits plus other savings-like deposits.

QUESTION: The U.S. penny, with Abraham Lincoln’s image on the front, has been in circulation since 1909. Back then, pennies were inexpensive to produce and could be used to purchase real items. Today, a U.S. penny actually costs the government more than one cent to produce, and it is virtually unusable in any coin-operated machine and impractical to use in stores. How has the role of the penny changed over the past century in terms of its monetary functions (medium of exchange, unit of account, and store of value)?

Because the purchasing power of the penny has fallen significantly since its first introduction, its monetary role also has diminished. It still serves as a medium of exchange, though the ease of its use has become so difficult that pennies often are left in coin jars, tip jars, and charity bins as opposed to kept for everyday use. Its function as a unit of account remains, since most prices are still quoted to the nearest penny. And its function as a store of value remains, though it requires a substantial jar of pennies before it is worth the time taking it to a coin exchange machine or to the bank.