Chapter Introduction

After studying this chapter you should be able to:

- Explain how banks create money by accepting deposits and making loans.

- Define fractional reserve banking and explain why banks can lend much more than they keep in reserves.

- Define banking regulations such as reserve requirements and deposit insurance.

- Explain how the money multiplier works and how it makes monetary policy decisions very powerful.

- Define a money leakage and explain how it affects the money multiplier.

- Describe the history and structure of the Federal Reserve System.

- Describe the Federal Reserve’s principal monetary tools.

- Explain how an open market operation works and how it affects interest rates.

- Explain why the Federal Reserve’s policies take time to affect the economy.

In small towns and villages throughout Central and South Asia, Africa, and Latin America, entrepreneurship is flourishing. These are not your typical high-tech start-ups or research and development centers, but rather primitive small shops selling basic goods and services. Many got their start using a microloan—a small loan (as little as $50) offered by organizations aiming to promote business enterprise among individuals who would not qualify for traditional bank loans.

These small loans and the new businesses they help create (largely by women in the poorest parts of the world) have been credited with bringing more people out of poverty in recent years than direct foreign aid has. How can a tiny loan of $50 have such a positive effect on the economy?

Quite easily, in fact. In Bangladesh, Fatima takes her $50 loan and buys cotton to make a dozen sharis. She sells the sharis at the local outdoor market for a total of $120, of which she uses $50 to pay back her microloan and $70 to buy more cotton to make even more sharis. Only this time, she is debt-free, allowing her to use all her proceeds to expand her business and provide income for her family. Meanwhile, the $50 she paid back will be loaned to another entrepreneur, allowing another small business to get its start.

When a small loan is used to create a new business, jobs are created, which allows people to spend money at other businesses (also likely started from a microloan). The collective power of new businesses, jobs, and increased spending leads to healthy economic growth in the village, and it all started from a single microloan. Now, multiply this one case by the thousands of microloans being made available throughout the developing world, and the effect on reducing poverty is staggering. This example represents a microcosm of the global economy and the money creation process in which financial intermediaries play an important role.

During the recent 2007–2009 recession and ensuing economic recovery, the opposite effect was happening in the United States. The downturn caused a steep decline in consumer and business confidence. Individuals and firms were not in a spending mood as jobs were lost and wages cut, on top of falling home and stock prices.

When consumers are not eager to spend, businesses suffer. Business owners develop a much bleaker view of the economy and reduce investment. Businesses may even cut jobs, jobs that are important for economic recovery.

But this wasn’t the entire story. Financial institutions during this time also lacked a willingness to lend to individuals and businesses that actually wanted to spend and invest. Why weren’t the banks eager to lend? And why did the lack of lending slow the economic recovery?

The answer is surprisingly similar to the situation of the villager seeking a small loan. When the financial industry was jolted by massive losses in the aftermath of the housing and construction collapse, many banks failed while others barely survived or required government bailouts. The scare faced by banks led to a severe tightening in lending practices (which, ironically, is the type of prudent lending that might have prevented the financial crisis to begin with). The unwillingness of banks to lend money prolonged the period of time necessary for economic recovery.

Banks and the Federal Reserve

Banks create money by accepting deposits and making loans. This process is aided by the Federal Reserve, which influences interest rates and sets reserve requirements for member banks.

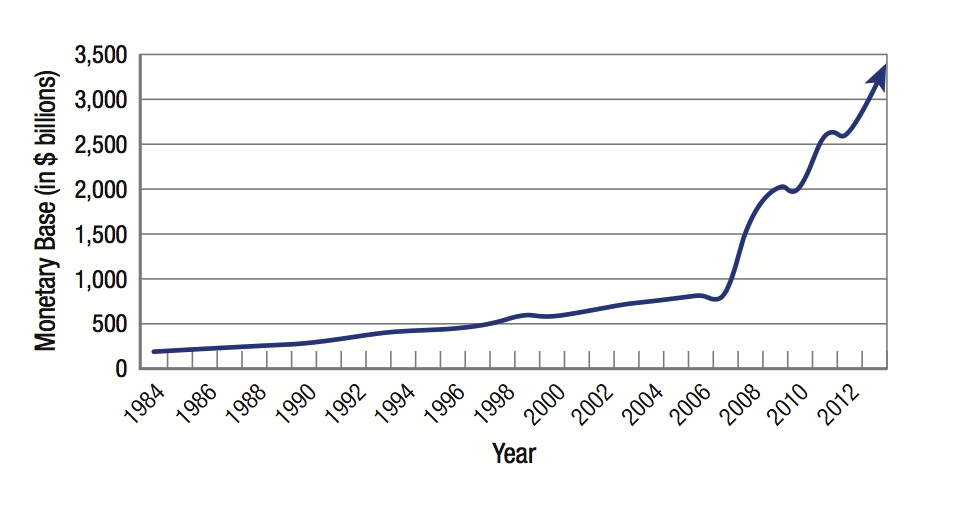

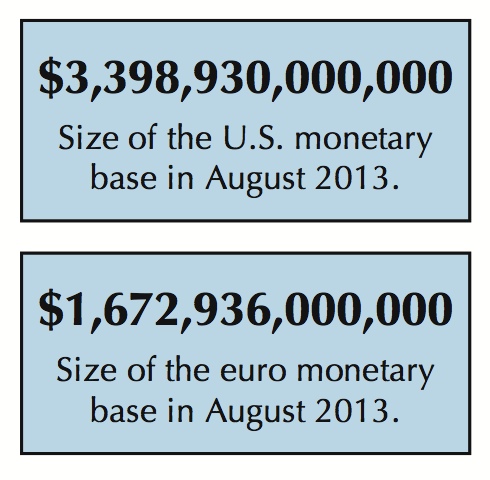

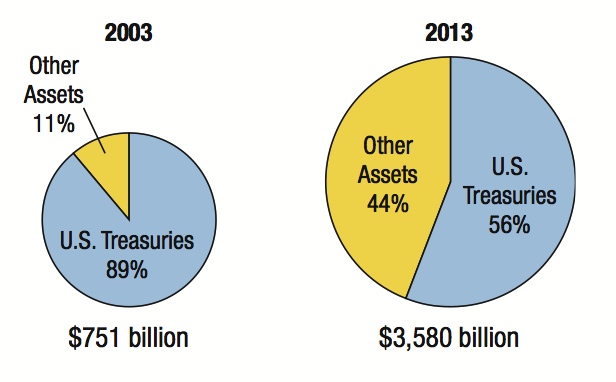

The monetary base is the sum of all currency in circulation and reserves held by banks. It grew steadily until the recent financial crisis, when aggressive action by the Federal Reserve caused the monetary base to skyrocket.

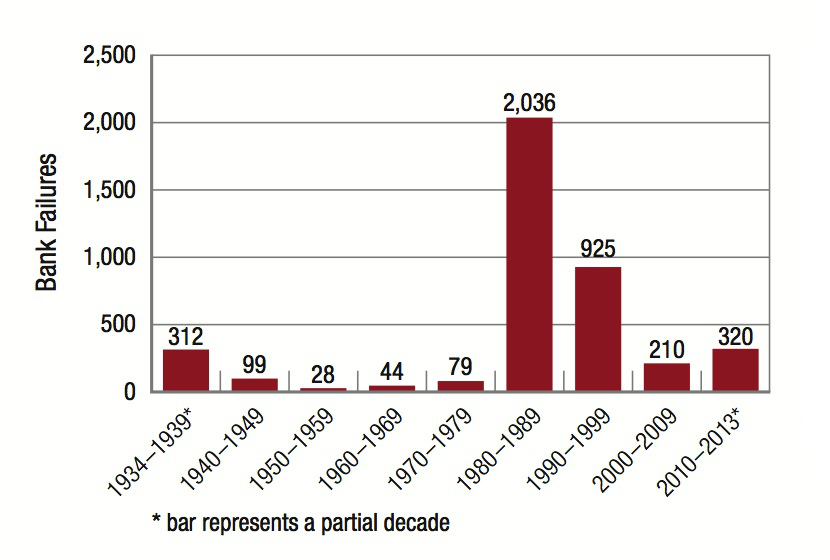

Bank failures were a major problem during the Great Depression in the 1930s, during the savings and loan crisis of the 1980s, and again during the most recent financial crisis. In fact, more banks failed in 2010 and 2011 than during the 40-year period from 1940 to 1979.

In 2008, Washington Mutual became the largest bank to fail in U.S. history.

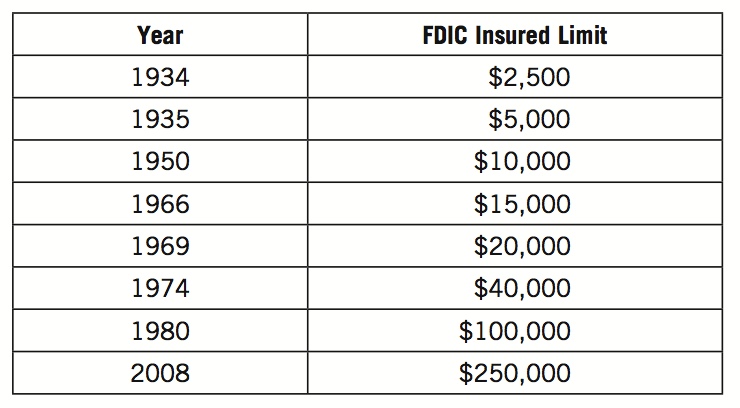

Individual bank accounts are protected against bank failure by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). No FDIC insured deposit has ever been lost in its history.

The Federal Reserve intervened heavily during the 2007–2009 financial crisis by increasing its purchases of underperforming assets from struggling banks. By doing so, the Fed altered its balance sheet in both its overall size and composition of assets.

In times when individuals and businesses are unwilling to spend and banks unwilling to lend, people begin to look elsewhere for help. For the small village, it was the emergence of the microloan organizations. For the U.S. economy, people turned to the government to take action.

The Federal Reserve (or Fed), the central bank of the United States, has extensive power in controlling the supply of money and interest rates, key elements in its arsenal of tools to jumpstart the economy when markets fail to do so on their own. In recent years, the Fed has taken dramatic steps to make borrowing less expensive for consumers and homeowners, and to provide banks with more capital and the confidence to lend to qualified borrowers.

This chapter takes a detailed look at the process by which banks go about creating money, as if out of thin air, by accepting deposits by savers and channeling these funds to borrowers.

We then study in more detail the role of the Federal Reserve, the guarantor of our money and our financial system. We will look at the history of the Fed, what it does with our money, and why it is called “the lender of last resort.” Lastly, we analyze the policies and tools the Fed can use to influence the money supply and interest rates.