How Banks Create Money

When most people think of money being created, the typical images conjured up are of large machines at government institutions printing sheets of crisp new banknotes or a large mint hammering out shiny new coins. Although this is indeed money creation in the literal sense, in reality currency represents less than half of the money supply, as we saw in the previous chapter.

Most money that we use every day does not involve cash and coins, but rather a sophisticated system of electronic debits and credits to our bank accounts. For example, unless one works primarily for cash tips or runs a small business where most purchases are paid for in cash, most of us will receive either a physical paycheck or a direct deposit of our wages into our bank accounts. Similarly, when we make purchases, most of us might use a debit or a credit card.

Given that most transactions today do not involve cash, the idea of creating money takes on an additional meaning, one in which banks play a very important role in its process.

Creating Money as if Out of Thin Air

Suppose that you run a small tutoring service helping students at your school succeed in (or at least pass) their economics courses. Some of your clients pay you with a personal check at the end of their session, while others give you cash. Let’s assume that this month, you received a total of $500 in checks, which you deposit into your checking account, and $500 in cash, which you keep in your safe at home. Your goal is to save as much of your tutoring earnings as possible in order to buy a new car. Aside from the potential forgone interest earnings and the temptation to spend the cash, does it really matter whether you put the cash in the bank or not?

To you, it doesn’t. If you need the money, you could just as easily go to an ATM to withdraw the cash as it is to take the cash out of your safe. But for the economy, there is in fact an important difference. The $500 you hold in cash is available to you—and only you—to use. However, the $500 in checks you had deposited in your bank account is money that others can use until you eventually need it. How is it that other people can use your money and yet this money is still available for you to take out when you need it?

Banks hold deposits from many customers at one time, and only a small portion is withdrawn on any given day, which the banks service using the reserves they keep on hand. The rest is lent out to borrowers who pay interest to the bank, part of which is then used to pay interest on the deposits the bank holds. The deposits and lending that occur in a bank starts the money creation process.

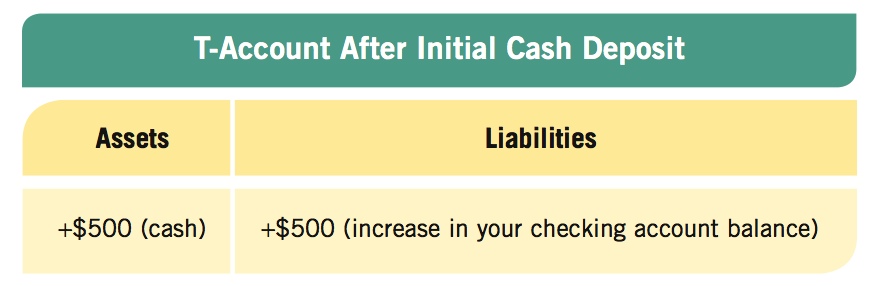

To illustrate the power of the money creation process, suppose you decide to take your $500 in cash and deposit it into your checking account. Let’s analyze how the bank uses this money using a simplified balance sheet comparing a bank’s assets (money the bank claims) and liabilities (money the bank owes) called a T-account. Liabilities are shown on the right side of the T-account. When you deposit money into the bank, it becomes a liability for the bank—the bank owes you this money. To balance out this liability, however, the bank now has an asset consisting of the cash from your deposit. Assets are shown on the left side of the T-account.

The following T-account shows an increase in the bank’s assets by $500 (the cash that you deposit that the bank now holds). On the right side, the bank’s liabilities increase by $500 because it must give back the $500 when you ask for it.

It is important to note that based on this initial transaction, no new money has been created in the economy. Why? Cash and demand deposits (checking accounts) are both components of the money supply measured as M1. By taking cash and converting it into a checkable deposit, there is now $500 less cash in circulation, but $500 more in checkable deposits, for a net change in M1 of 0.

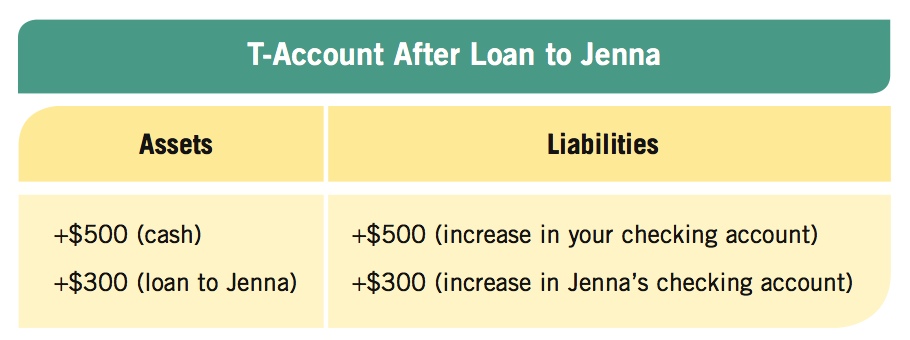

But the process is just beginning. Now that the bank has additional cash reserves, it can lend some of this money to someone else. Suppose another customer at the same bank, Jenna, is running low on cash and needs to take out a small loan of $300 to cover bills that are coming up at the end of the month. How would the bank handle this?

The bank would create a $300 loan for Jenna (which becomes an asset to the bank), and add $300 to Jenna’s checking account for her to use when needed. The following shows the new T-account for the bank.

After the loan to Jenna is made, the total amount of checkable deposits has now increased by $800 based on the initial $500 cash deposit. In other words, the bank has created $300 in money, as if out of thin air, simply by making a loan to Jenna.

reserve ratio The percentage of a bank’s total deposits that are held in reserves, either as cash in the vault or as deposits at the regional Federal Reserve Bank.

reserve requirement The required ratio of funds that commercial banks and other depository institutions must hold in reserve against deposits.

The obvious question would now be—Couldn’t the bank just keep making infinite amounts of loans? The answer is that the bank needs to have enough funds in place should you or Jenna decide to make a withdrawal from your account to pay bills or make purchases. Thus, a bank’s ability to make loans is limited to a certain percentage of its total customer deposits. In other words, a bank must keep some reserves (such as cash) on hand to cover day-to-day withdrawals. The level of reserves a bank holds as a percentage of total deposits is called its reserve ratio. Further, the government requires that banks maintain a minimum level of reserves called the reserve requirement.

In our example, the reserve ratio is calculated by: reserves/total deposits, which in this case is $500/($500 + $300) = 62.5%. Because most reserve requirements are much lower than this percentage, this bank is considered highly liquid, and may continue to make more loans using your initial cash deposit until the reserve ratio drops down toward its reserve requirement.

Up until now, we have assumed that all loans and deposits occurred at the same bank, but this need not be true. In fact, most money transactions in our economy take place between banks. But the way in which we analyzed loans and deposits and how that leads to money being created does not change. Our example above describes the process of a fractional reserve banking system.

Fractional Reserve Banking System

Banks loan money for consumer purchases and business investments. Assume that you deposit $1,000 into your checking account and the bank then loans this $1,000 to a local business to purchase some machinery. If you were to go to the bank the next day and ask to withdraw your funds, how would the bank pay you? The bank could not pay you if you were its only customer. Banks, however, have many customers, and the chance that all these customers would want to withdraw their money on the same day is small.

fractional reserve banking system Describes a banking system in which a portion of bank deposits are held as vault cash or in an account with the regional Federal Reserve Bank, while the rest of the deposits are loaned out to generate the money creation process.

excess reserves Reserves held by banks above the legally required amount.

Such “runs on the bank” are rare, normally occurring only when banks or a country’s currency are in trouble. In the United States, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) protects bank deposits (up to $250,000 per account) from bank failure. When a bank gets into financial trouble, the FDIC typically arranges for another (healthy) bank to take over the failing bank, resulting in virtually no interruption of services to the bank’s customers. The bank takeover usually occurs late on a Friday and the bank reopens on Monday morning under a new name. Because most accounts are insured, it is business as usual on Monday.

It was the possibility of bank runs that led to the fractional reserve banking system. When someone deposits money into a bank account, the bank is required to hold part of this deposit in its vault as cash, or else in an account with the regional Federal Reserve Bank. We will learn more about the Federal Reserve System later in this chapter, but for the moment, let us continue to concentrate on how fractional reserve banking permits banks to create money.

The Money Creation Process Banks create money by lending their excess reserves, or reserves above the reserve requirement. When money is loaned out, it eventually is deposited back into the original bank or some other bank. The bank will again hold some of these new deposits as reserves, loaning out the rest. The whole process continues until the entire initial deposit is held as reserves somewhere in the banking system.

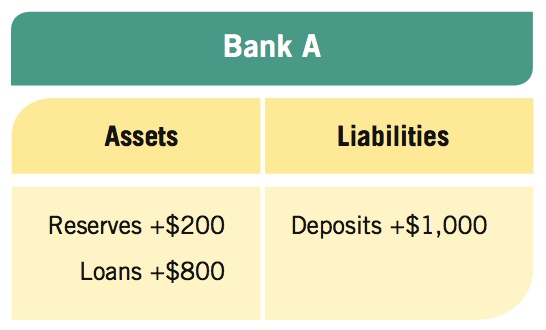

Assume that the Federal Reserve sets the reserve requirement at 20%. This means that banks must hold 20% of each deposit as reserves, whether in their vaults or in accounts with the regional Federal Reserve Bank. Now assume that you take $1,000 out of your personal safe at home and take it to Bank A. Bank A puts 20% of your $1,000 into its vault as reserves and loans out the rest. Its T-account balance sheet now reads:

As the balance sheet indicates, your $1,000 deposit is now a liability for Bank A. But the bank also has new assets, split between reserves and loans. In each of the transactions that follow, we assume banks become fully loaned-up, loaning out all they can and keeping in reserves only the amount required by law.

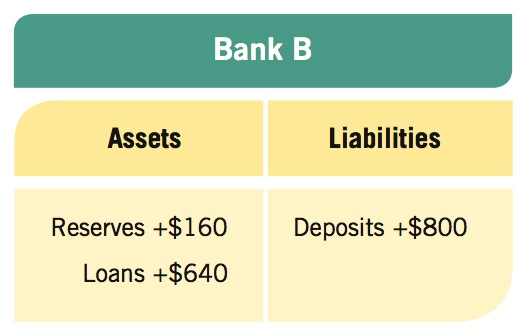

Assume that Bank A loans out the $800 it has in excess funds to a local gas station, and assume that this money is deposited into Bank B. Bank B’s balance sheet now reads:

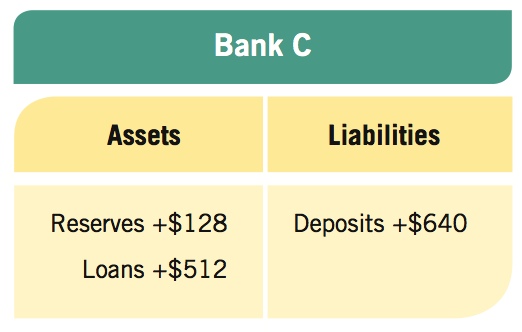

Bank B, in other words, has new deposits totaling $800. Of this, the bank must put $160 into reserves; the remaining $640 it loans out to a local winery. The winery deposits these funds into its bank, Bank C. This bank’s balance sheet shows:

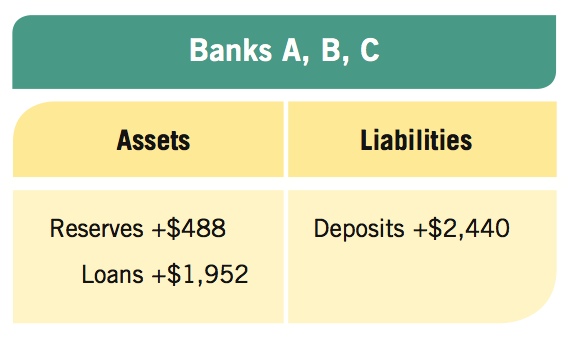

Summing up the balance sheets of the three banks shows that total reserves have grown to $488 ($200 + $160 + $128), loans have reached $1,952 ($800 + $640 + $512), and total deposits are $2,440 ($1,000 + $800 + $640). Your original $1,000 new deposit has caused the money supply to grow.

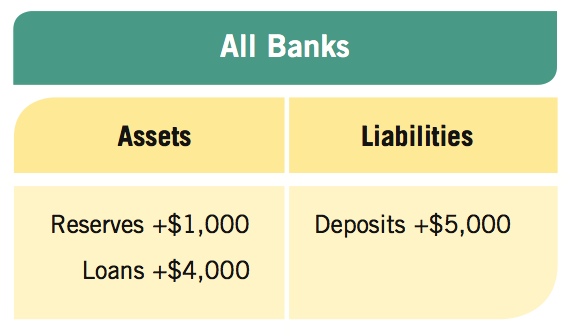

This process continues until the entire $1,000 of the original deposit has been placed in reserves, thus raising total reserves by $1,000. By this point, all the banks together will have loaned out a total of $4,000. A summary balance sheet for all banks reads:

Notice what has happened. Keeping in mind that demand deposits form part of the money supply, your original deposit of $1,000—cash that was injected into the banking system—has turned into $5,000 in deposits, a $4,000 increase in the money supply. Bank reserves, in other words, have gone up by your initial deposit, but beyond this, an added $4,000 has been created. And this was made possible because banks were allowed to loan part of your deposit to consumers and businesses.

The ability of banks to take an initial deposit of cash and turn it into loans and deposits many times over (5 times the initial deposit in our example) demonstrates the power of the banking system to create money. Moreover, the initial deposit of cash need not come from an individual; in fact, much of the money creation that occurs in the economy begins with deposits made by the government, as we will see later in this chapter.

HOW BANKS CREATE MONEY

- Money is created when banks make loans to customers, because these funds are eventually deposited into other banks as checkable deposits.

- The fractional reserve system permits banks to create money through their ability to accept deposits and make loans.

- The reserve ratio is the fraction of total customer deposits held in reserves.

- The reserve requirement is the minimum reserve ratio banks must follow.

- A T-account is a simplified bank balance sheet showing assets (money banks lay claim to) and liabilities (money banks owe).

QUESTIONS: Suppose that you go to your bank and withdraw $1,000 from your checking account to spend on your Spring Break vacation to the Caribbean. If the bank has plenty of cash to pay you without falling below its reserve requirement or changing the amount of loans it has, would the money supply M1 change? Would the money supply change if the bank had planned to loan out its excess reserves?

The basic transaction reduces your checking account by $1,000 and adds $1,000 in cash for your trip. Therefore, M1 would stay the same because cash and checkable deposits are both part of M1. However, by withdrawing $1,000 from the bank, this is $1,000 that could be loaned out by the bank and lead to money creation. Therefore, by making the withdrawal, the money supply would drop if the bank had planned to loan out its excess reserves.