The Federal Reserve System

Federal Reserve System The central bank of the United States.

The Federal Reserve System is the central bank of the United States. It controls an immense power to create money in the economy.

Early in U.S. history, banks were private and chartered by the states. In the 1800s and early 1900s, bank panics were common. After an unusually severe banking crisis in 1907, Congress established the National Monetary Commission. This commission proposed one central bank with sweeping powers. But a powerful national bank became a political issue in the elections of 1912, and the commission’s proposals gave way to a compromise that is today’s Federal Reserve System.

The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 was a compromise between competing proposals for a huge central bank and for no central bank at all. The act declared that the Fed is “to provide for the establishment of Federal Reserve Banks, to furnish an elastic currency, to afford means of rediscounting commercial paper, to establish a more effective supervision of banking in the United States, and for other purposes.”

Since 1913, other acts have further clarified and supplemented the original act, expanding the Fed’s mission. These acts include the Employment Act of 1946, the International Banking Act of 1978, the Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act of 1978, the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act of 1991.

The original Federal Reserve Act, the Employment Act of 1946, and the Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act of 1978 all mandate national economic objectives. These acts require the Fed to promote economic growth accompanied by full employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates. As we will see in the next chapter, meeting all of these objectives at once has often proved difficult.

The Federal Reserve is considered to be an independent central bank, in that its actions are not subject to executive branch control. The entire Federal Reserve System is, however, subject to oversight from Congress. The Constitution invests Congress with the power to coin money and set its value, and the Federal Reserve Act delegated this power to the Fed, subject to Congressional oversight. Though several presidents have disagreed with Fed policy over the years, the Fed has always managed to maintain its independence from the executive branch.

Experience in this country and abroad suggests that independent central banks are better at fighting inflation than are politically controlled banks. The main reason is that an independent central bank is less likely to be influenced by short-term political pressures to engage in excessive expansionary monetary policy to hasten a recovery.

The Structure of the Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 passed by Congress led to the establishment of regional banks governed by a central authority. The intent was to provide the Fed with a broad perspective on the economy, with the regional Federal Reserve Banks contributing economic analysis from all parts of the nation, while still investing a central authority with the power to carry out a national monetary policy.

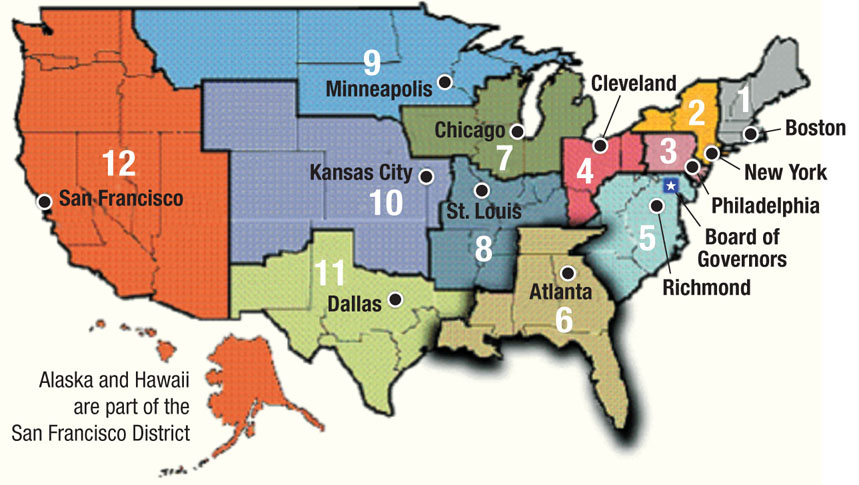

The Fed is composed of a central governing agency, the Board of Governors, located in Washington, D.C., and twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks in major cities around the nation. Figure 1 shows the twelve Fed districts and their bank locations.

FIGURE 1

Regional Federal Reserve Districts The twelve regional Federal Reserve districts and their bank locations.

The Board of Governors The Fed’s Board of Governors consists of seven members who are appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Board members serve terms of 14 years, after which they cannot be reappointed. Appointments to the Board are staggered such that one term expires on January 31 of every even-numbered year. The chairman and the vice chairman of the Board must already be Board members; they are appointed to their leadership positions by the president, subject to Senate confirmation, for terms of four years. The Board of Governors’ staff of nearly 2,000 helps the Fed carry out its responsibilities for monetary policy, and banking and consumer credit regulation.

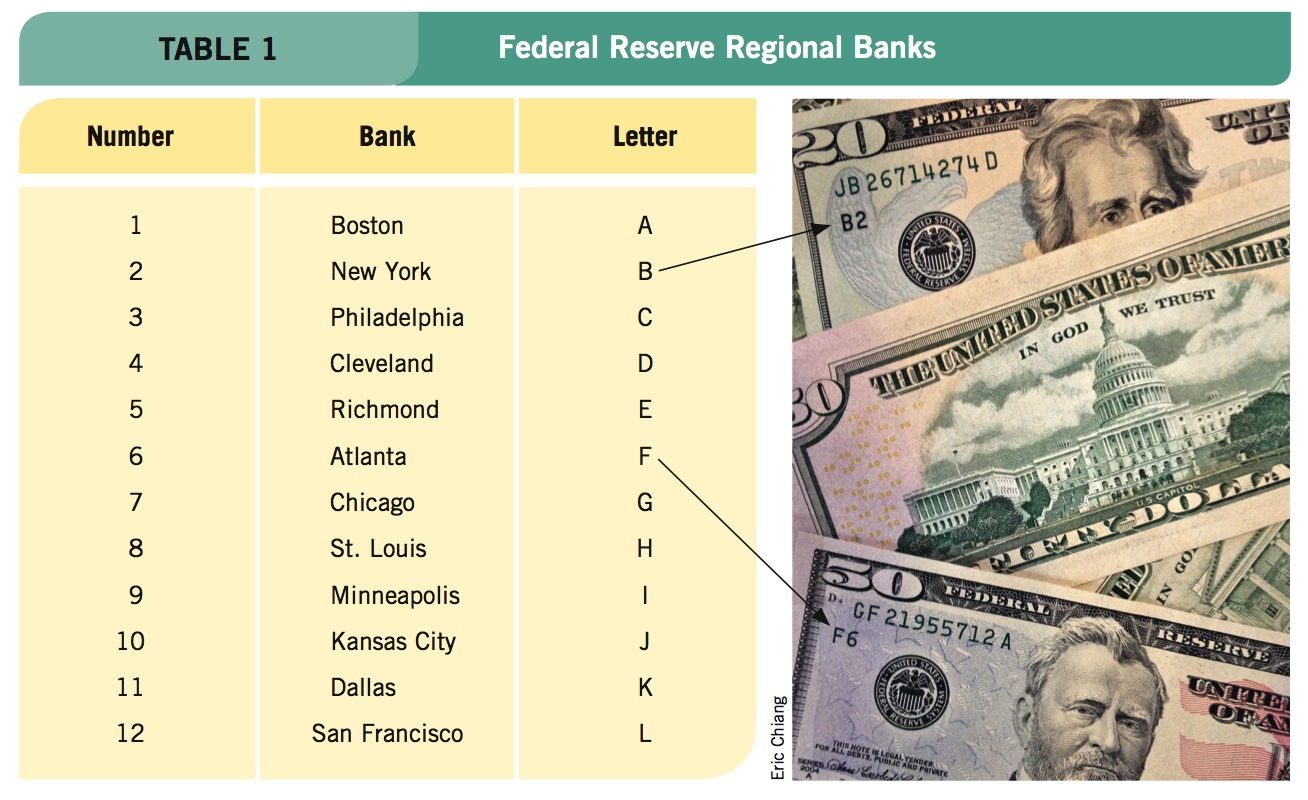

Federal Reserve Banks Twelve Federal Reserve Banks and their branches perform a variety of functions, including providing a nationwide payments system, distributing coins and currency, regulating and supervising member banks, and serving as the banker for the U.S. Treasury. Table 1 lists all regional banks and their main locations. Each regional bank has a number and letter associated with it. If you look at your money, you will see that all U.S. currency bears the designation of the regional bank where it was first issued, as shown in Table 1.

Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) A twelve-member committee that is composed of members of the Board of Governors of the Fed and selected presidents of the regional Federal Reserve Banks. It oversees open market operations (the buying and selling of government securities), the main tool of monetary policy.

Each regional bank also provides the Federal Reserve System and the Board of Governors with information on economic conditions in its home region. Eight times a year this information is compiled into a report—called the Beige Book—that details the economic conditions around the country. These reports are provided to the Board of Governors first, and later released to the public. The Board and the Federal Open Market Committee use the information the Beige Book contains to determine the course of the nation’s monetary policy.

Federal Open Market Committee The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) oversees open market operations, the main tool of monetary policy. Open market operations involve the buying and selling of government securities. How these open market operations influence reserves available to banks and other thrift institutions will become clear shortly.

The FOMC is composed of the seven members of the Board of Governors and five of the twelve regional Federal Reserve Bank presidents. The president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York is a permanent member because actual open market operations take place at the New York Fed. The other four members are appointed for rotating one-year terms. All regional presidents participate in FOMC deliberations, but only those serving on the committee vote. Traditionally, the chairman of the Board of Governors has also served as the chairman of the FOMC.

The Fed as Lender of Last Resort The essence of banking, as we have seen, is that banks take in short-term deposits (liabilities) and make long-term, often illiquid, loans (assets). This puts banks in the unique position of facing extraordinary withdrawals when people panic and all want their money at the same time. Banks typically do not have sufficient reserves to stem a full-fledged financial panic. They cannot turn these long-term loans into cash. During a panic, banks would be forced to dump the securities or loans onto the market at a deep discount (or “take a haircut” in modern parlance), potentially forcing them into insolvency. Lending to banks during financial panics—being a lender of last resort—is a principal reason for the existence of central banks.

The value of the Fed’s ability to provide loans during a financial crisis stood out during the financial panic in late 2008. The Fed extended credit where none was available. As markets collapse during financial panics, banks become reluctant to lend out money to businesses and to other banks that need cash in an emergency. This is when the Fed steps in.

In just a few months, the Fed extended more than $2 trillion in loans to banks and other financial institutions, and by doing so changed the allocation of assets in its balance sheet in ways not seen since it was created in 1913. Specifically, instead of holding primarily government treasury securities, in late 2008 the Fed was holding more bank assets (such as mortgage-backed securities) than treasury securities.

Had the Fed and its lender of last resort capability not been available, the 2007–2009 recession would have been much deeper and could possibly have resulted in another depression. The ability of the Fed to make loans and inject the banking system with new money allows the fractional banking process to work and prevents the economy from facing a much worse financial crisis.

THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM

- The Federal Reserve System is the central bank of the United States.

- The Federal Reserve is structured around twelve regional banks and a central governing agency, the Board of Governors.

- The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) oversees open market operations for the Federal Reserve.

- The Federal Reserve serves as the lender of last resort, stepping in to loan money to banks that are facing cash emergency shortages.

QUESTION: If a large portion of a bank’s customers want their money back at the same time and other banks won’t lend to it, what can the Federal Reserve do to prevent a run on the bank?

The Federal Reserve has the power to loan the struggling bank the money to satisfy the withdrawals. However, such withdrawals are often a sign of deeper underlying troubles at the bank. The question then becomes whether to let the bank fail and be taken over by a solvent bank, or to help it survive by purchasing bad debts and recapitalizing the bank.