The Federal Reserve at Work: Tools, Targets, and Policy Lags

With an ability to alter the money supply, both directly and indirectly through the money multiplier, the Federal Reserve has remarkable powers to conduct monetary policy, its primary role. And because it acts independently of political parties, the Fed is able to set monetary policy with remarkable efficiency, especially compared to fiscal policy, which involves the ever common wrangling between political parties in Congress and the president. For this reason, monetary policy is often looked at as a way to provide quicker remedies to economic conditions facing the country.

But how is monetary policy actually carried out? Quite remarkably, the Federal Reserve uses just three primary tools for conducting monetary policy:

- Reserve requirements—The required ratio of funds that commercial banks and other depository institutions must hold in reserve against deposits.

- The discount rate—The interest rate the Federal Reserve charges commercial banks and other depository institutions to borrow reserves from a regional Federal Reserve Bank.

- Open market operations—The buying and selling on the open market of U.S. government securities, such as Treasury bills and bonds, to adjust reserves in the banking system.

Reserve Requirements

The Federal Reserve Act specifies that the Fed must establish reserve requirements for all banks and other depository institutions. As we have seen, this law gives rise to a fractional reserve system that enables banks to create new money, expanding demand deposits through loans. The potential expansion depends on the money multiplier, which in turn depends on the reserve requirement. By altering the reserve ratio, the Fed can alter reserves in the system and alter the supply of money in the economy.

Banks hold two types of reserves: required reserves and excess reserves above what they are required to hold. Roughly 15,000 depository institutions, ranging from banks to thrift institutions, are bound by the Fed’s reserve requirements. Reserves are kept as vault cash or in accounts with the regional Federal Reserve Bank. These accounts not only help satisfy reserve requirements, but are also used to clear many financial transactions.

federal funds rate The interest rate financial institutions charge each other for overnight loans used as reserves.

Banks are assessed a penalty if their accounts with the Fed are overdrawn at the end of the day. Given the unpredictability of the volume of transactions that may clear a bank’s account on a given day, most banks choose to maintain excess reserves.

At the end of the day, banks and other depository institutions can loan one another reserves or trade reserves in the federal funds market. One bank’s surplus of reserves can become loans to another institution, earning interest (the federal funds rate). A change in the federal funds rate reflects changes in the market demand and supply of excess reserves.

In 2008, the Fed changed its long-standing law of not paying interest on reserves. The new law allowed banks to earn interest on the reserves it deposits at the Fed. This law changed the incentives faced by banks by reducing the opportunity cost of choosing not to lend. In other words, in tough economic times, banks may choose to forgo making loans (especially risky ones) in favor of earning interest on their excess reserves deposited at the Fed. As we saw in the previous section, when banks hold more excess reserves, the money multiplier falls.

By raising or lowering the reserve requirement, the Fed can add reserves to the system or squeeze reserves from it, thereby altering the supply of money. Yet, changing the reserve requirement is almost like doing surgery with a bread knife; the impact is so massive and imprecise that the Fed rarely uses this tool.

Discount Rate

discount rate The interest rate the Federal Reserve charges commercial banks and other depository institutions to borrow reserves from a regional Federal Reserve Bank.

The discount rate is the rate regional Federal Reserve Banks charge depository institutions for short-term loans to shore up their reserves. The discount window also serves as a backup source of liquidity for individual depository institutions.

The Fed extends discount rate credit to banks and other depository institutions typically for overnight balancing of reserves. The rate charged is roughly 1 percentage point higher than the FOMC’s target federal funds rate. However, most banks avoid using the discount window out of fear that it might arouse suspicion by both their customers and by the Fed that they are facing financial trouble.

But during the banking crisis that started in 2007, the government was more interested in banks making prudent decisions than avoiding the stigma of borrowing from the Fed. To encourage banks to use the discount window when needed, in August 2007 the rate was lowered to 0.5 percentage point above the federal funds rate. As noted earlier, the federal funds rate is the interest rate that banks and other financial institutions with excess reserves charge other banks for overnight loans to help them shore up their reserves. As we will see in the following, this is an important target for Federal Reserve policy.

Neither the discount rate nor the reserve requirement, however, gives the Fed as much power to implement monetary policy as open market operations. Open market operations allow the Fed to alter the supply of money and system reserves by buying and selling government securities.

Open Market Operations

open market operations The buying and selling of U.S. government securities, such as Treasury bills and bonds, to adjust reserves in the banking system.

When one private financial institution buys a government security from another, funds are redistributed in the economy; the transaction does not change the amount of reserves in the economy. When the Fed buys a government security, however, it pays some private financial institution for this bond; therefore, it adds to aggregate reserves by putting new money into the financial system.

Open market operations are powerful because of the dollar-for-dollar change in reserves that comes from buying or selling government securities. When the FOMC buys a $100,000 bond, $100,000 of new reserves is instantly put into the banking system. These new reserves have the potential to expand the money supply as banks make loans.

Open market operations are the most important of the Fed’s tools. When the Fed decides on a policy objective, the volume of bonds being traded in open market operations to achieve that objective can be staggering. With the bond market valued in the trillions, it requires billions of dollars in bond transactions in order for the FOMC to push the federal funds rate toward its target.

The Federal Funds Target The target federal funds rate is the Fed’s primary approach to monetary policy. As we will see in the next chapter, targeting the federal funds rate through open market operations gives the Fed an ability to influence the price level and output in the economy, a very powerful effect. The FOMC meetings result in a decision on the target federal funds rate, which is announced at the end of the meeting. Keep in mind that the federal funds rate is not something that the Fed directly controls. Banks lend overnight reserves to each other in this market, and the forces of supply and demand set the interest rate.

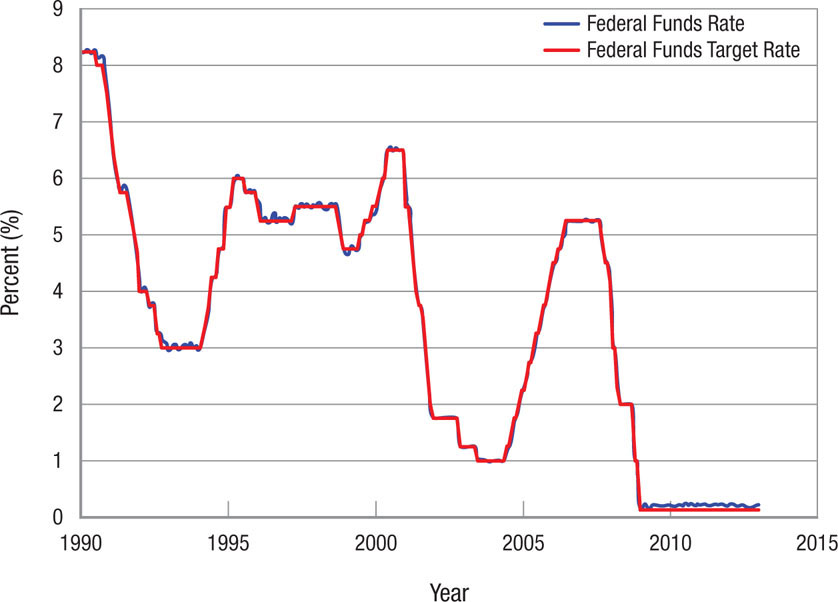

The Fed uses open market operations to adjust reserves and thus change nominal interest rates with the goal of nudging the federal funds rate toward the Fed’s target. When the Fed buys bonds, its demand raises the price of bonds, lowering nominal interest rates in the market. The opposite occurs when the Fed sells bonds and adds to the market supply of bonds for sale, lowering prices and raising the nominal interest rate. The Fed has actually been pretty good at keeping the federal funds rate near the target, as Figure 2 illustrates.

FIGURE 2

The Federal Funds Rate and Target Federal Funds Rate In the last two decades, the Fed has been very successful at hitting its federal funds target rate.

In summary, typically the Fed sets a target for the federal funds rate and then uses open market operations to manipulate reserves to alter the money supply. Changing the money supply alters market interest rates to bring the federal funds rate in line with the Fed’s target. Open market purchases increase reserves, reducing the need for banks to borrow, lowering the federal funds rate, and vice versa for open market sales. The key thing to note here is that the Fed does not directly control the money supply: It proceeds indirectly, though it has been very successful in meeting its goals.

Monetary Policy Lags

Although the Fed has a remarkable ability to use tools that have important impacts on interest rates, bank reserves, and the money supply, they can still take time to have an effect on the economy. Like fiscal policy, monetary policy is subject to four major lags: information, recognition, decision, and implementation. The combination of these lags can make monetary policy difficult for the Fed. Not only does the Fed face a moving bull’s-eye in terms of its economic targets, but often it can be difficult for the Fed to know when its own policies will take effect and what their effect will be.

Information Lags We discussed information lags when we discussed fiscal policy lags: Economic data are available only after a lag of one to three months. Therefore, when an economic event takes place, changes may ripple throughout the economy for up to three months before monetary authorities begin to see changes in their data. Many economic measures published by the government, moreover, are subject to future revision. It is not uncommon for these revisions to be so significant as to render the original number meaningless. Thus, it might take the Fed several quarters to identify a changing trend in prices or output clearly.

Recognition Lags Simply seeing a decline in a variable in one month or quarter does not necessarily mean that a change in policy is warranted. Data revisions upward and downward are common. In the normal course of events, for instance, unemployment rates can fluctuate by small amounts, as can GDP. A quarter-percent decline in the rate of growth of GDP does not necessarily signal the beginning of a recession, although it could. Nor does a quarter-percent increase in GDP mean that the economy has reached the bottom of a recession; double-dip recessions are always a possibility. Because of this recognition lag, policymakers are often unable to recognize problems when they first develop.

Decision Lags The Federal Reserve Board meets roughly on a monthly basis to determine broad economic policy. Therefore, once a problem is recognized, decisions are forthcoming. Decision lags for monetary policy are shorter than for fiscal policy. Once the Fed makes a decision to, say, avert a recession, the FOMC can begin to implement that decision almost immediately. As Figure 2 illustrates, once the Fed decides on a federal funds target, nominal interest rates track that target in a hurry. In contrast, fiscal policy decisions typically require administrative proposals and then Congressional action.

Implementation Lags Once the FOMC has decided on a policy, there is another lag associated with the reaction of banks and financial markets. Monetary policy affects bank reserves, interest rates, and decisions by businesses and households. As interest rates change, investment and buying decisions are altered, but often not with any great haste. Investment decisions hinge on more than just interest rate levels. Rules, regulations, permits, tax incentives, and future expectations (what Keynes called “animal spirits”) all enter the decision-making process.

Economists estimate that the average lag for monetary policy is between a year and 18 months, with a range varying from a little over one quarter to slightly over two years. Using monetary policy to fine-tune the economy requires more than skill—some luck helps.

This chapter began with a discussion of how banks create money by lending excess reserves from their customer deposits or from the sale of bonds to the Federal Reserve. The power of the fractional banking system to generate money many times over allows the Fed to wield this power in several ways, mainly by targeting the federal funds rate using open market operations. The next chapter looks more deeply into how the Fed uses its monetary tools to balance its goals of keeping income growing and prices stable.

What Can the Fed Do When Interest Rates Reach 0%?

At the height of the 2007–2009 recession, the Federal Reserve used aggressive expansionary policy to prevent a much more severe recession or even a depression. The Fed did so by reducing the federal funds rate target, the interest rate that influences almost all other interest rates in the economy. By December 2008, the Federal Reserve had lowered the federal funds rate target to essentially 0%. Yet, the economy was still struggling and needed additional help to prevent a deeper recession. But with interest rates already at 0%, what else could the Fed do?

The Fed developed new ways to expand the money supply without using its regular open market operations. First, it purchased poorly performing assets from banks, such as mortgage-backed securities, in an effort to remove these bad assets from bank balance sheets.

Second, in August 2007 the Fed reduced the difference between the federal funds target rate and the discount rate and used term auction facilities to encourage borrowing by banks that typically would not borrow from the Fed out of fear it would signal that the bank was in trouble. In an effort to reduce this stigma, the Fed essentially auctioned money for banks to borrow, taking interest rate bids from banks. This tool allowed many banks to borrow money at rates lower than the discount rate without facing the consequences from doing so. It also improved bank liquidity, making it easier for banks to lend to individuals and businesses.

Then came the tool often considered to be the last resort to stimulating the economy, quantitative easing, or QE. With quantitative easing, the Fed purchased huge amounts of bank debt, mortgage-backed securities, and long-term treasury notes, all with money it created electronically. Between 2008 and 2013, four rounds of quantitative easing (called QE1, QE2, QE3, and QE4, respectively) dramatically increased the Fed’s balance sheet and more than doubled the monetary base (currency in circulation plus bank reserves).

It is difficult to quantify the success of the Fed’s efforts. Critics of the Fed’s actions point to the fact that unemployment remained high and economic growth barely improved years after the recession ended. But supporters of the Fed argue that had the Fed not taken these actions, the economy might have entered a depression.

In situations such as these, economists often wonder about the counterfactual, or what would have happened if the Fed hadn’t engaged in these policies. The reality is that we may never know, because once a decision is made, it is not possible to determine what would have happened using another approach. Regardless, the positive signs of an improving economy suggest that whether or not the Fed’s actions played a pivotal role, there is no question that the Fed’s power in controlling the money supply remains a very powerful tool that influences our lives in many ways.

THE FEDERAL RESERVE AT WORK: TOOLS, TARGETS, AND POLICY LAGS

- The Fed’s tools include altering reserve requirements, changing the discount rate, and open market operations (the buying and selling of government securities).

- The Fed uses open market operations to keep the federal funds rate at target levels.

- The Fed’s policies, as with fiscal policy, are subject to information, recognition, decision, and implementation lags. Unlike fiscal policy, the Fed’s decision lags tend to be shorter because Fed policies are not subjected to lengthy legislative processes.

QUESTIONS: Of the three tools used by the Fed, open market operations are the most common. Why is the Fed more hesitant about adjusting the reserve requirement and the discount rate? What can go wrong?

Open market operations are very effective because they influence virtually all interest rates. Reducing the reserve requirement can certainly boost lending; however, reducing it too much can put banks at risk should defaults rise. Adjusting the discount rate is generally less effective, because bank customers and investors often view borrowing from the discount window as a warning sign of the bank’s deteriorating financial health. As a result, the Fed typically keeps the discount rate at a fixed level slightly above the federal funds rate.