The Great Recession and Macroeconomic Policy

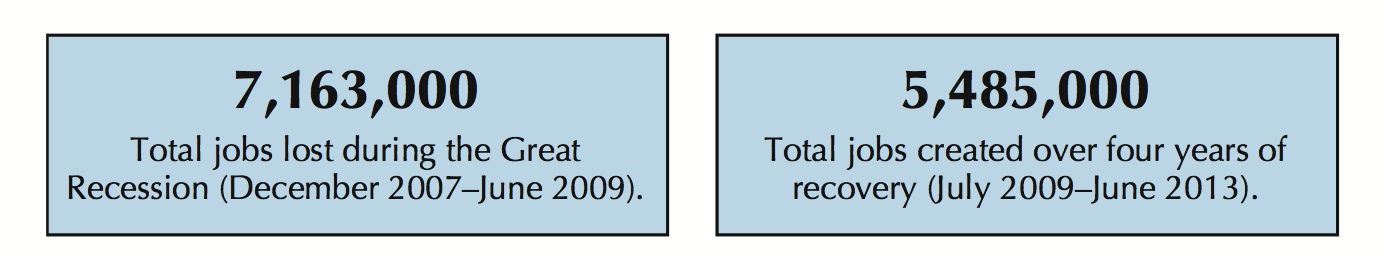

The 18-month recession that lasted from December 2007 to July 2009 was dubbed the Great Recession, not because of its length, which was not much longer than the typical recession, but rather for its severity and the impact it had on so many industries and countries. Further, the economic recovery that took place after the recession was slow, requiring many years for economic indicators to return to their prerecession levels. The unemployment rate, for example, remained above 7% even four years after the recession ended. This section presents the factors that led to the Great Recession and the macroeconomic policies used to mitigate its effects.

The Long Road Back: The Great Recession and the Jobless Recovery

The Great Recession was caused by the collapse of the housing market, which led to reduced consumer sentiment and lower retail sales. Persistent unemployment ensued and the Fed used unprecedented monetary policy actions to speed up the economic recovery.

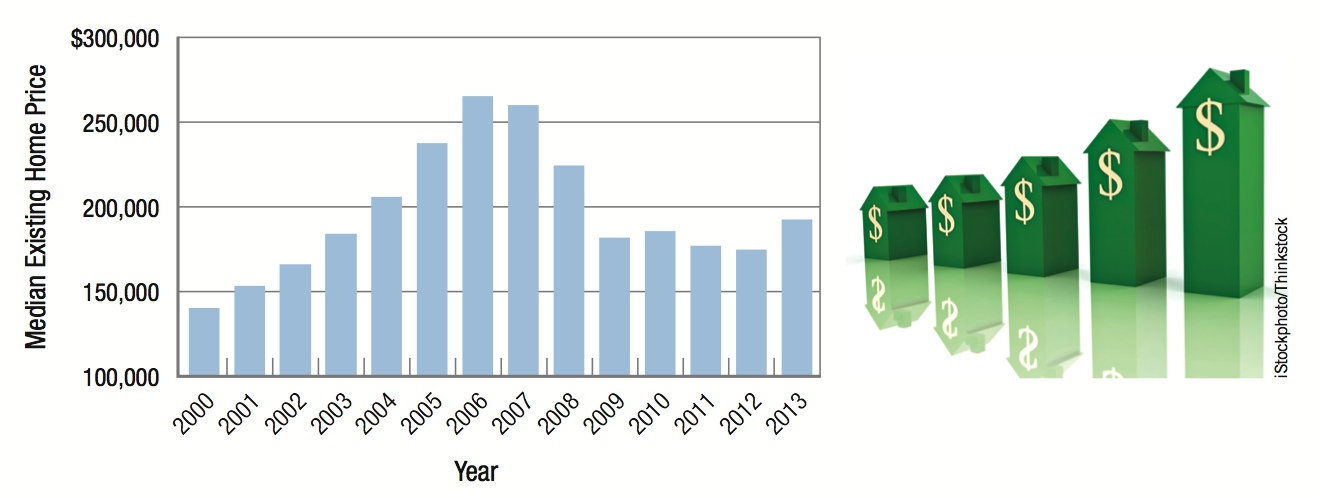

Median existing home prices rose significantly in the early years of the 21st century but fell quickly in the latter part of the decade. Housing prices have since risen again.

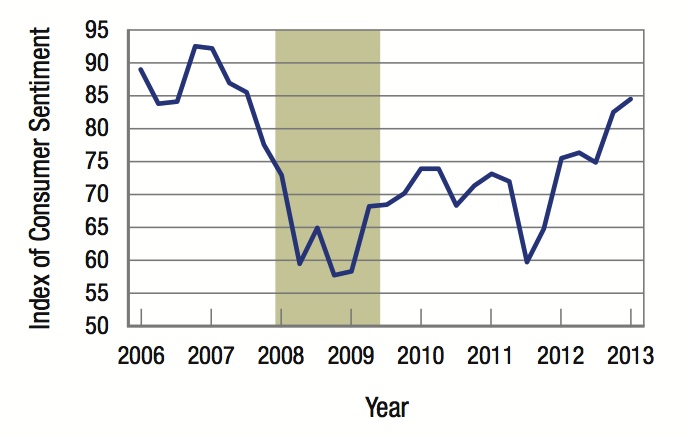

Consumer sentiment fell from 2007 to 2009. It has since risen with the economic recovery; however, as of 2013 consumer sentiment had not returned to its prerecession peak.

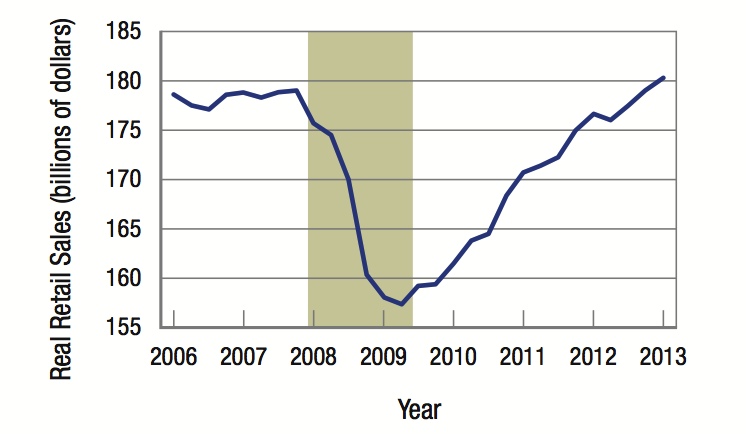

Monthly real retail sales fell over 10% from 2007 to 2009. It took four years for real retail sales to recover and to surpass the level reached in 2007.

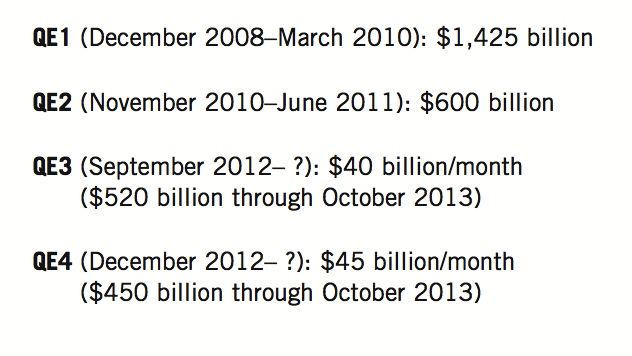

The Federal Reserve undertook four rounds of quantitative easing (QE) after short-term interest rates were effectively lowered to 0%. The value of assets purchased in each round:

The Fed’s actions kept long-term interest rates low, encouraging consumers and businesses to borrow in order to consume and invest. But would lenders lend?

From the Housing Bubble to the Financial Crisis

Owning a home is a dream shared by most people. During the first few years of the 21st century, a glut in worldwide savings and the Fed’s aggressive expansionary monetary policies following the 2001 recession led to low mortgage rates, helping many to achieve that dream of home ownership. Renters bought their first homes. Existing homeowners moved into larger homes or bought second homes. The resulting higher than normal demand drove up the price of housing. After a few years of rising prices, people started to think prices could only go up. This led some people to become speculators, which led to house “flipping”—purchasing a home with the intention of selling it as soon as possible for a tidy profit.

Builders provide homes, but usually a third party brings the transaction to a close: A financial intermediary provides the financing for home buyers in the form of a mortgage. For many years, the standard mortgage was a 30-year mortgage with a fixed interest rate. The person taking out the mortgage to purchase the home made monthly payments, which consisted of interest on the loan and some payment toward the loan amount (the principal). Financial intermediaries, such as banks, usually had high standards that would-be home buyers had to meet. Further, a home buyer’s income and credit quality were rigorously checked by the financial intermediaries.

This changed at the beginning of the new century, as banks eager to cash in on the lucrative housing market made loans easier to obtain. And, as long as housing prices kept rising, the borrower’s collateral (the house) would protect the bank from losing money if the loan could not be repaid. Financial intermediaries encouraged home buying by offering adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs). These mortgages offered a below-market interest rate for a short period (usually three or five years); the rate would then adjust based on the market interest rate. From a buyer’s point of view, a below-market rate, at least in the short term, was an inducement to buy. From a bank’s point of view, below-market rates generated business: They could expect ARM holders to seek out fixed interest rate mortgages after the initial period ended, which meant a second round of origination fees (paid whenever a mortgage is taken out).

subprime mortgage Mortgages that are given to borrowers who are a poor credit risk. These higher-risk loans charge a higher interest rate, which can be profitable to lenders if borrowers make their payments on time.

The housing boom of 2003 to 2007 saw even more innovations in the mortgage market, as financial intermediaries felt competitive pressure from new mortgage brokers and Wall Street firms that were only too happy to meet the growing demand. Two key things happened: Mortgage credit standards fell, and the market for collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) developed.

Subprime Mortgages and Collateralized Debt Obligations Subprime mortgages are loans made to borrowers with poor credit. These loans carried high interest rates that were profitable for the banks as long as borrowers made payments on time. Because the economy was strong, defaults were minimal. Further, many financial institutions reduced their risk by selling off these loans to other investors in the form of CDOs, also known as mortgage-backed securities (which make up most CDOs).

CDOs are essentially bonds backed by a collection of mortgages: prime, subprime, home equity, and other ARMs. Banks holding mortgages found they could offset the risk of default by selling them to consolidators who put together enormous packages of CDOs, with the mortgaged homes standing as the collateral behind the security offered. Wall Street then sold off slices of these mortgage pools to investors interested in the steady income from mortgage payments. Mortgages to subprime borrowers—people with a lower ability to pay or who were poor credit risks for other reasons—could be combined with solid mortgages, a little like diluting poison in a large lake to dissipate its effects.

Banks and mortgage companies now were evaluating mortgage clients for loans that they did not intend to keep. They were simply collecting an origination fee and then immediately selling the mortgage to Wall Street. What in the past had been a long-term investment for banks and mortgage companies became nothing more than a business of advertising and selling loans quickly. Because Wall Street could package and sell as many loans as mortgage brokers could provide, banks had less incentive to keep high lending standards based on credit history and large down payments. Risk was being transferred elsewhere. People, no matter how bad their credit history, could get a loan for a piece of real estate without putting any money down. In one extreme and famous case, a farm laborer with an annual income of $14,000 was given a $720,000 loan on a Bakersfield, California, home.

Trouble started in 2007 when some of the people who took on subprime mortgages started to default. These people were stretched too thin. When their ARMs reset, they faced higher payments, sometimes double or triple the original monthly payments. Worse, the spike in foreclosures as well as homeowners trying to sell their homes to escape rising mortgage payments caused the value of houses to fall, which meant that borrowers wishing to refinance their homes (to make mortgage payments affordable again) were being turned away because the amount they were seeking to borrow exceeded the value of their now lower-value home.

leverage Occurs when investors borrow money at low interest rates to purchase investments that may provide higher rates of return. The risk of highly leveraged investments is that a small decrease in price can wipe out one’s account.

Compounding this, another problem arose. Risk ratings by bond rating agencies whose job it is to rate packages of mortgages turned out to be faulty. Wall Street knew the minimum requirements needed for a rating agency to assign a AAA rating to a CDO, and they manipulated the components to get that all-important rating. Also, rating firms were paid 6 times their normal fee to give the AAA rating to the mortgage packages, and were only paid if the CDO got the AAA rating, giving ratings agencies an incentive to lower standards. Investors wanted bonds with the security of a AAA rating, which gave the appearance of high-yield, low-risk investments. The bond packages sold well all over the world. The risk of each CDO was underestimated because of the overly rosy ratings.

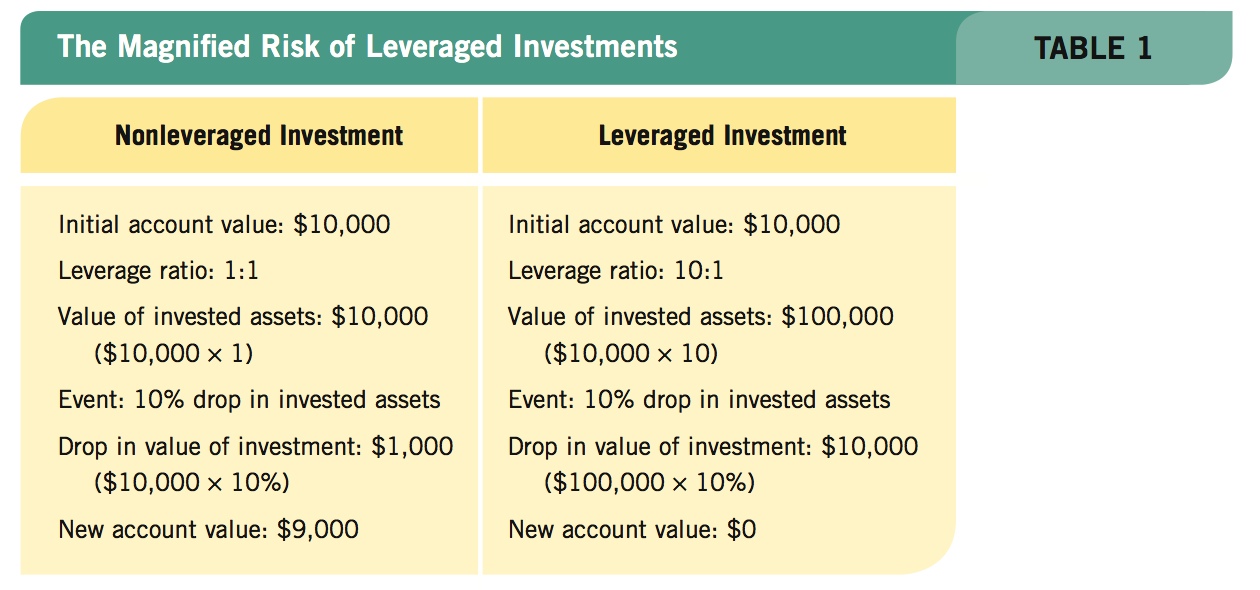

Two more problems would make this a growing house of cards. Because the mortgage packages were seen as low-risk investments, many investors borrowed money at the low prevailing interest rates to purchase greater quantities. They leveraged their capital to earn greater returns. But with leverage comes additional risk: A small drop in prices can easily wipe out a highly leveraged account. Table 1 shows how a leveraged investment magnifies the risk of losing money. In this case, a 10% drop in value of the security wipes out the leveraged account, while the nonleveraged account sees its value drop by just 10%. A leveraged account magnifies both gains and losses.

credit default swap A financial instrument that insures against the potential default on an asset. Because of the extent of defaults in the last financial crisis, issuers of credit default swaps could not repay all of the claims, bankrupting these financial institutions.

To protect against this risk, investors purchased credit default swaps, an instrument developed by the financial industry to act as an insurance policy against defaults. The biggest issuer of credit default swaps, the American Insurance Group (AIG), sold several trillion dollars of these swaps with only a few billion dollars in capital to back them up. Here again we see risk underestimated, and therefore mispriced.

Collapsing Financial Markets This brings us to the central event that brought down the financial system. By 2007, $25 trillion of American CDOs were in investment portfolios of banks, pension funds, mutual funds, hedge funds, and other financial institutions worldwide. The rate of subprime mortgage defaults was on the rise: Up to a quarter of the mortgages in CDOs might default, representing a default rate 10 times greater than that anticipated by the AAA rating models. Because investors did not know what exactly was in their CDOs (the prospectuses were impenetrable), they panicked and tried to sell these investments.

Because the CDOs were too complex to evaluate, the market collapsed. Buyers evaporated, and prices fell as people began dumping CDOs at fire-sale prices. AIG could not cover the losses it had insured and went bankrupt. For banks, this was a catastrophe. Their CDOs were virtually worthless, and an important part of the banks’ capital was wiped out. To raise capital, banks called in loans and reduced lines of credit to businesses, which reduced the money supply, contracted the economy, caused job losses, and deepened the recession.

In sum, the financial crisis was caused by a savings glut that led to low interest rates, which fueled a housing boom that led to new financial instruments and investment securities that depended on the value of housing staying high. A financial house of cards was created, and when one card at the bottom (subprime loans) lost strength, the entire edifice fell. Because all types of financial institutions worldwide were investors in CDOs, credit dried up, creating a credit crisis that precipitated a worldwide recession.

The Government’s Policy Response

As long as the financial system takes on risks that it misperceives, we will have financial crises. Let’s look at the government’s policy response to the financial crisis:

- Bear Stearns: In July 2007, Bear Stearns, a large Wall Street investment bank, liquidated two hedge funds that invested in mortgage-backed securities as they started to collapse. By March 2008, with Bear Stearns on the verge of bankruptcy due to its holdings of mortgage-backed securities, the Fed engineered a takeover of Bear Stearns by Chase Bank. In essence, the Fed was bailing out a rogue bank. This kept a lid on things for a while, but not for long.

- Lehman Brothers: Stung by criticism of its Bear Stearns bailout, the Fed let Lehman Brothers, the fourth largest commercial bank, fail on September 15, 2007. The Fed and the Treasury thought they were sending a message to the financial markets that imprudent behavior such as that displayed by Lehman Brothers would result in tremendous costs to stockholders and executives. Unfortunately, this decision sent the financial markets into a tailspin, as banks lost faith in other banks, and insolvencies rose throughout the financial sector.

- AIG: The market received another shock in September when AIG announced it was bankrupt. The news of its bankruptcy turned AAA-rated CDO bonds into highly discounted junk bonds. To stem the panic, the Fed lent AIG over $100 billion.

- TARP: In October 2008, Congress responded to the crisis by passing the $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), authorizing the U.S. Treasury to purchase CDOs from banks to shore up their capital. The U.S. Treasury ended up investing in banks by injecting government money for preferred equity (stock), thereby increasing bank capital and eliminating insolvency.

- Public Concerns: Policymakers were concerned about public confidence in banks and worried that depositors might begin withdrawing funds, putting banks at further risk of failure. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) increased its guarantee on deposits from $100,000 to $250,000 per account.

- The 2009 Stimulus Package: One of President Obama’s first pieces of legislation in his first term was passing the $787 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, a fiscal policy aimed to boost aggregate demand following the financial crisis and recession.

- Industry Bailouts: The financial crisis had also depressed consumer demand, which led many industries to face collapse. In 2009, the government loaned significant sums of money to General Motors, Chrysler, and Ford to save the U.S. automobile industry. Today, the U.S. automobile industry is profitable and strong: In 2012, each of the three major automobile companies made substantial profits and combined earned a profit of $13.2 billion.

- Fed’s Quantitative Easing Programs: Over the next several years, the Fed would continue to buy mortgage-backed securities in order to remove these risky assets from bank balance sheets. The effort was unprecedented, with the Fed accumulating over $1 trillion in mortgage-backed securities by 2012.

These extraordinary efforts prevented the widespread bank failures that had plagued the economy during the Great Depression and during the Savings and Loan Crisis in the 1980s. For the Fed, it was crucial to maintain public confidence and keep the recession from becoming a full-blown depression. The Fed stepped far outside of its usual role of managing the money supply, interest rates, inflation, and unemployment, and took extraordinary, lender-of-last-resort measures to prevent a financial sector meltdown.

This brief summary of the government’s response during the financial crisis outlines the breadth and depth of fiscal and monetary policies designed to avert a catastrophe. They have succeeded, but the cost may not be known for a decade.

The Financial Crisis and Its Effects

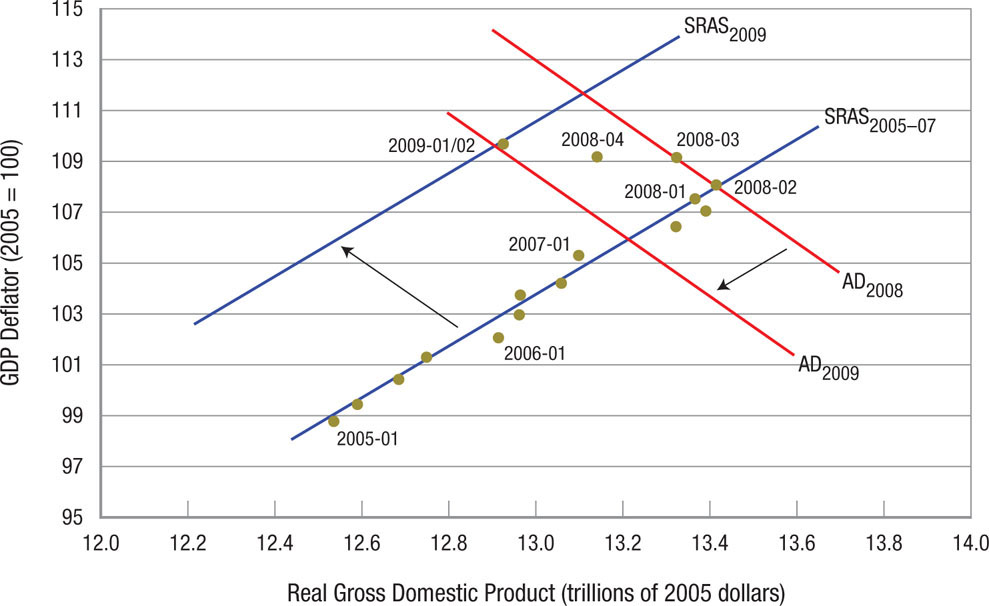

The economy grew nicely between 2005 and the end of 2007. Inflation was low and the economy grew at about 2.5% a year. When we discussed lags in a previous chapter, we saw how it takes time to ascertain when an economy enters a recession. In hindsight, it is easy to see when this recession started. Figure 1 shows hypothetical aggregate demand and short-run aggregate supply curves superimposed over the actual data for the years 2005 to 2009. Follow the dots and you can see progressive growth in real GDP until the end of 2007. This recession began at the end of 2007 and accelerated in 2008 until the middle of 2009. Real GDP declined by over 4% and unemployment reached 10% of the labor force.

FIGURE 1

The 2007–2009 Recession This figure illustrates the 2007–2009 downturn by using real GDP and the GDP deflator data for 2005 through 2009 and superimposing hypothetical aggregate demand and short-run aggregate supply curves on the data. Because of the financial crisis, consumer spending declined, reducing aggregate demand in 2008 and 2009. Layoffs ensued and short-run aggregate supply declined as well. During this period, real output declined by over 4%.

How can we explain this shift in aggregate demand and short-run aggregate supply? The recession was brought on by the financial crisis, which in turn was brought on by the mispricing of the risk of subprime mortgages and by excessive consumer debt. At the onset of the financial crisis, jobs were cut as consumers reduced their spending: They tightened their belts in an effort to reduce household debt levels and hunkered down for what they perceived as a severe recession on the way. As a result, 7 million people lost their jobs during this two-year period. Job losses reduced consumer confidence, further reducing consumer spending, which shifted aggregate demand from AD2008 toward AD2009. As demand dropped, businesses reduced their production capacity through layoffs and plant closings, shifting short-run aggregate supply leftward from its original trajectory at SRAS2005–2007 to that shown as SRAS2009.

Toward the end of the recession, prices began to fall as deflation set in for most of 2009. We have spent a considerable time in this book studying the harmful effects of inflation, yet now the economy faced deflation. Deflation can be a problem because it increases the real value of existing debt, making the debt more burdensome and requiring more purchasing power to make interest payments or pay off the debt. Policymakers faced the problem of preventing debt from becoming a more serious burden on households, which would further reduce aggregate demand and deepen the recession.

Financial Crises and Macroeconomic Policy

For most college students, the 2007–2009 financial crisis and the accompanying recession represents their first experience with a serious downturn in the economy. The previous two slumps (1990–1991 and 2001) were shallow and lasted only eight months, but were followed by a period of slow job growth.

The savings and loan collapse (our last banking crisis) happened nearly 30 years ago, therefore most people under 45 cannot recollect its impact. Over the last 40 years, Europe, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand have endured a total of 18 bank-centered financial crises.

One of the themes of financial crises is excessive debt accumulation by consumers, firms, banks, and government, which creates a greater risk to the economy during downturns. Bailouts resulting from financial crises are expensive and recessions are costly both for the government and for the people unemployed. More distressing is that recessions associated with bank-centered financial crises tend to last much longer.

The tools we learned about in previous chapters helped us to understand how the government managed the most recent financial crisis. Let’s take a further step, adding in some challenges to the effective use of policy to smooth the business cycle. The next section focuses on the effectiveness of macroeconomic policy by considering the Phillips curve, which proposes a tradeoff between unemployment and inflation. If this tradeoff exists, policymaking becomes simple: Pick some rate of unemployment and face a corresponding rate of inflation. We also look at how the rational expectations model questions whether using macroeconomic policy to correct fluctuations in the business cycle can ever be effective at all.

THE GREAT RECESSION AND MACROECONOMIC POLICY

- A world savings glut and low interest rates from 2003–2007 led to a housing price bubble. Consumers were eager to buy homes, developers were eager to build them, banks were eager to lend money to purchasers, and investors were eager to invest in CDOs.

- Financial risk was not properly accounted for in the period leading up to the financial crisis, and ratings agencies gave too many CDOs a AAA rating that wasn’t deserved.

- When the housing bubble collapsed, foreclosures on subprime mortgages sent the economy into a recession.

- To control the panic, the Fed used its normal monetary policy tools and some that it hadn’t used since the 1930s in its role as lender of last resort.

- Congress used fiscal policy in an attempt to nullify the drop in aggregate demand caused by the financial crisis.

QUESTION: The U.S. housing bubble in the early 21st century was caused by a number of factors that provided incentives to individuals to buy houses, to businesses to build and sell houses, and to financial institutions to loan money. In hindsight, what are some policies that the government could have implemented to mitigate this housing bubble?

Had it been known that the collapse of the housing market bubble would have caused a severe financial crisis, the government could have implemented macroeconomic policies to slow the rise in housing prices. For example, the government could (1) use contractionary monetary policy to push interest rates higher, making it more expensive to borrow money; (2) pass regulations on financial institutions requiring greater scrutiny of potential borrowers; (3) limit the types of risky loans that could be created; and (4) eliminate tax incentives on housing market profits to limit house flipping.