The Terms of Trade

How much can a country charge when it sells its goods to another country? How much must it pay for imported goods? The terms of trade determine the prices of imports and exports.

To keep things simple, assume that each country has only one export and one import, priced at Px and Pm. The ratio of the price of the exported goods to the price of the imported goods, Px/Pm, is the terms of trade. Thus, if a country exports computers and imports coffee, with two computers trading for one ton of coffee, the price of a computer must be one-half the price of a ton of coffee.

terms of trade The ratio of the price of exported goods to the price of imported goods (Px/Pm).

When countries trade many commodities, the terms of trade are defined as the average price of exports divided by the average price of imports. This can get a bit complicated, given that the price of each import and export is quoted in its own national currency, while the exchange rate between the two currencies may be constantly changing. We will ignore these complications by translating currencies into dollars, focusing our attention on how the terms of trade are determined and the impact of trade.

379

Determining the Terms of Trade

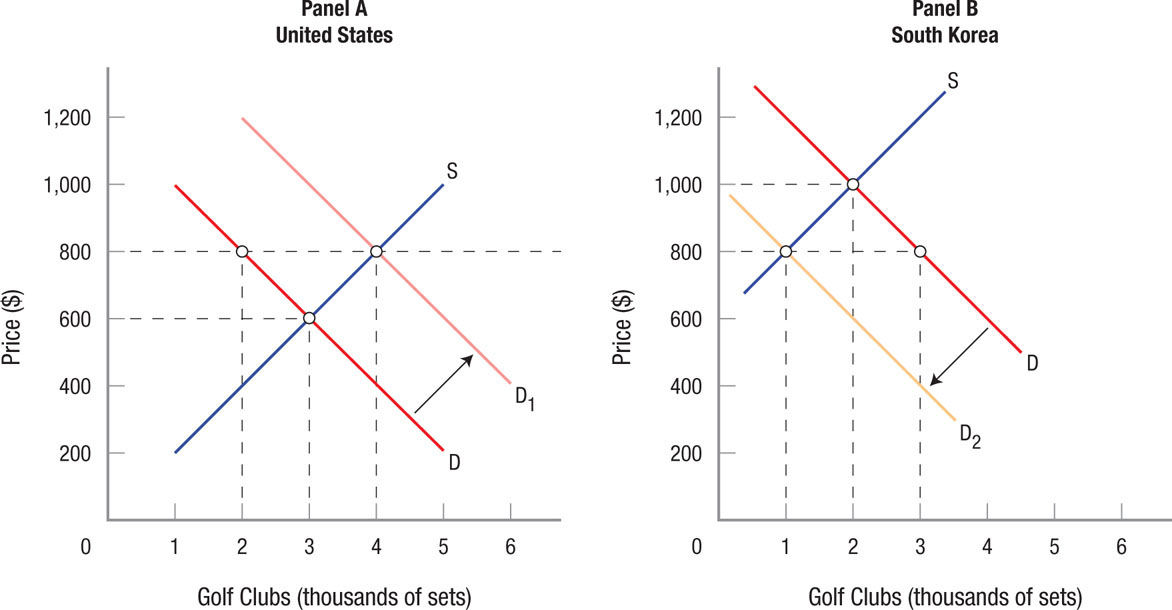

To get a feel for how the terms of trade are determined, let us consider the trade in golf clubs between the United States and South Korea. We will assume the United States has a comparative advantage in producing golf clubs; all prices are given in dollars.

Panel A of Figure 4 shows the demand and supply of sets of golf clubs in the United States. The upward sloping supply curve reflects increasing opportunity costs in golf club production. As the United States continues to specialize in golf club production, resources less suited to this purpose must be employed, resulting in rising costs for golf club production. Because of this rise in costs as ever more resources are shifted to golf clubs, the United States will eventually lose its comparative advantage in golf club production. This represents one limit on specialization and trade.

Let us assume that the United States begins in pretrade equilibrium, with the price of sets of golf clubs at $600 each. Panel B shows South Korea initially in equilibrium with a higher price of $1,000. Because prices for golf clubs from the United States are lower, when trade begins, Korean consumers will begin buying U.S. golf clubs.

380

American golf club makers will increase production to meet this new demand. Korean golf club firms, conversely, will see the sales of their golf clubs decline. For now, let us ignore transport costs, such that trade continues until prices reach $800. At this point, U.S. exports (2,000 sets of golf clubs) are just equal to Korean imports. Both countries are now in equilibrium, with the price of golf clubs somewhere between the two pretrade equilibrium prices ($800 in this case).

Imagine this same process simultaneously working itself out with many other goods, including some at which the Koreans have a comparative advantage, such as interactive televisions. As each product settles into an equilibrium price, the terms of trade between these two countries is determined.

The Impact of Trade

Our examination of absolute and comparative advantage has thus far highlighted the benefits of trade. A closer look at Figure 4, however, shows that trade produces winners and losers.

Picking up on the previous example, golf club producers in the United States are happy, having watched their sales rise from 3,000 to 4,000 units. Predictably, management and workers in this industry will favor even more trade with South Korea and the rest of the world. Yet, domestic consumers of golf clubs are worse off, because after trade they purchase only 2,000 sets at the higher equilibrium price of $800.

Contrast this situation in the net exporting country, the United States, with that of the net importer, South Korea. Korean golf club producers are worse off than before because the price of golf clubs fell from $1,000 to $800, and their output was reduced to 1,000 units. Consequently, they must cut jobs, leaving workers and managers in the Korean golf club industry unhappy with its country’s trade policies. Korean consumers, however, are beneficiaries of this expanded trade, because they can purchase 3,000 sets of golf clubs at a lower price of $800 each.

These results are not merely hypothetical. This is the story of free trade, which has been played out time and time again: Some sectors of the economy win, and some lose. American consumers have been happy to purchase Korean televisions such as Samsung and LG, given their high quality and low prices. American television producers (such as RCA and Zenith) have not been so pleased, nor have their employees, having watched television factories close and workers displaced as competition from abroad forced these companies out of business.

Wong Maye-E/AP Images

Similarly, the ranks of American textile workers have been decimated over the past three decades as domestic clothing producers have increasingly become nothing but designers and marketers of clothes, shifting their production overseas to countries in which wages are lower. American-made clothing is now essentially a thing of the past.

To be sure, American consumers have enjoyed a substantial drop in the price of clothing, because labor forms a significant part of the cost of clothing production. Still, being able to purchase inexpensive T-shirts made in China is small consolation for the unemployed textile worker in North Carolina.

The undoubted pain suffered by the losers from trade often is translated into pressure put on politicians to restrict trade in one way or another. The pain is often felt more strongly than the “happiness” felt by those who benefit from trade.

How Trade Is Restricted

Trade restrictions can range from subsidies provided to domestic firms to protect them against lower priced imports to embargoes by which the government bans any trade with a country. Between these two extremes are more intermediate policies, such as exchange controls that limit the amount of foreign currency available to importers or citizens who travel abroad. Regulation, licensing, and government purchasing policies are all frequently used to promote or ensure the purchase of domestic products. The main reason for these trade restrictions is simple: The industry and its employees actually feel the pain and lobby extensively for protection, while the huge benefits of lower prices are diffused among millions of consumers whose benefits are each so small that fighting against a trade barrier isn’t worth their time.

381

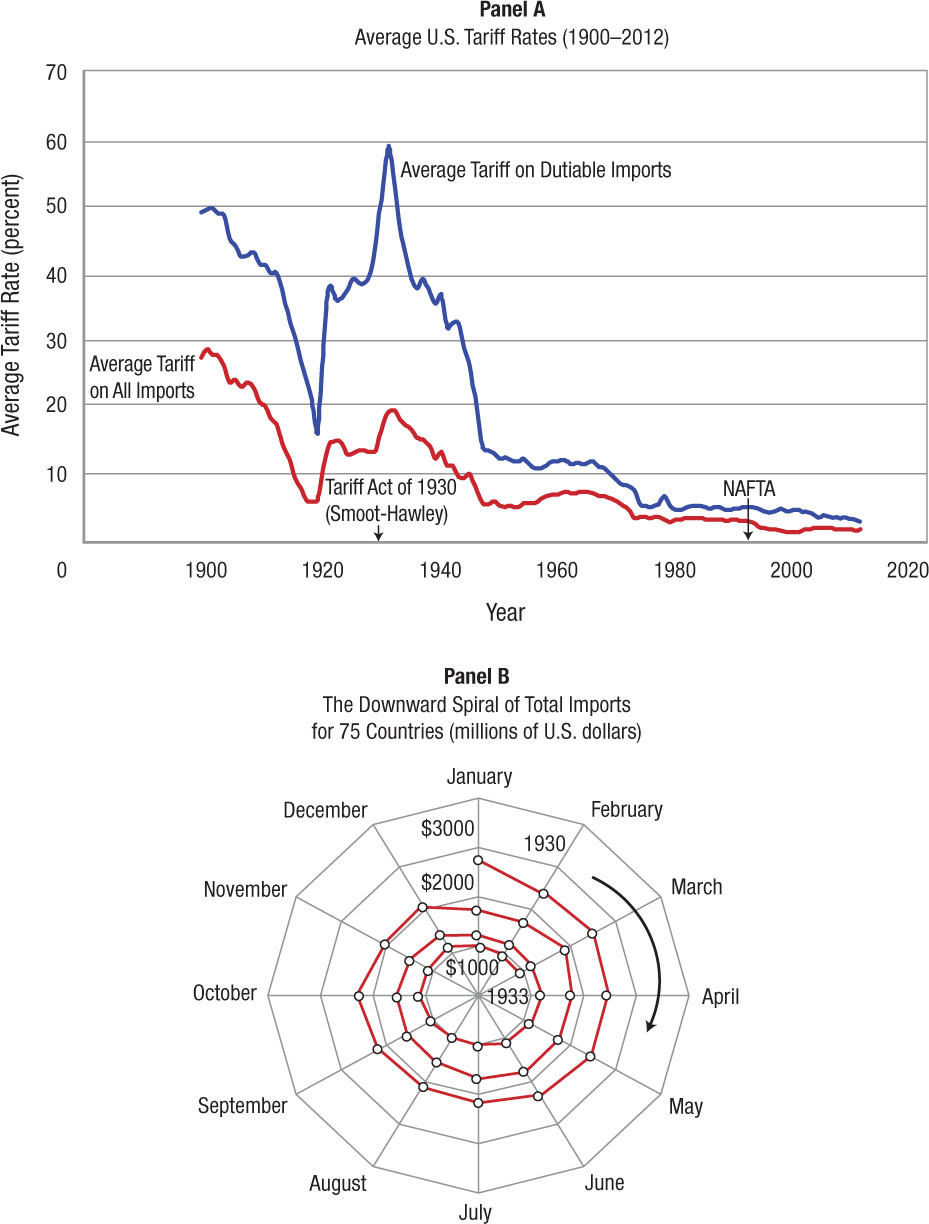

The most common forms of trade restrictions are tariffs and quotas. Panel A of Figure 5 shows the average U.S. tariff rates since 1900. Some economists have suggested that the tariff wars that erupted in the 1920s and culminated in the passage of the Smoot-Hawley Act in 1930 were an important factor underlying the severity of the Great Depression. Panel B shows the impact of higher tariffs on worldwide imports from 1930 to 1933. The higher tariffs reduced trade, leading to a reduction in income, output, and employment, and added fuel to the worldwide depression. Since the 1930s, the United States has played a leading role in trade liberalization, with average tariff rates declining to a current rate of roughly 2%.

Source: Charles Kindleberger, The World Depression 1929–1939 (Berkeley: University of California Press), 1986, p. 170.

382

Effects of Tariffs and Quotas

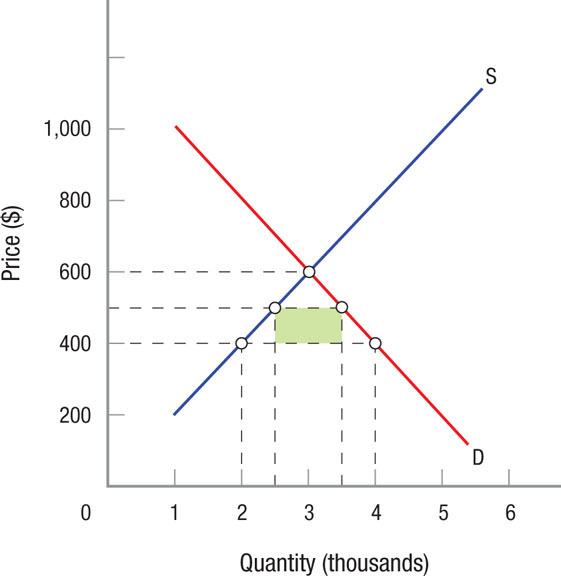

tariff A tax on imported products. When a country taxes imported products, it drives a wedge between the product’s domestic price and its price on the world market.

What exactly are the effects of tariffs and quotas? Tariffs are often ad valorem taxes. This means that the product is taxed by a certain percentage of its price as it crosses the border. Other tariffs are unit taxes (also known as specific tariffs): A fixed tax per unit of the product is assessed at the border. Tariffs are designed to generate revenues and to drive a wedge between the domestic price of a product and its price on the world market. The effects of a tariff are shown in Figure 6.

Domestic supply and demand for the product are shown in Figure 6 as S and D. Assume that the product’s world price of $400 is lower than its domestic price of $600. Domestic quantity demanded (4,000 units) will consequently exceed domestic quantity supplied (2,000 units) at the world price of $400. Imports to this country will therefore be 2,000 units.

Now assume that the firms and workers in the industry hurt by the lower world price lobby for a tariff and are successful. The country imposes a tariff of $100 per unit on this product. The results are clear. The product’s price in this country rises to $500 and imports fall to 1,000 units (3,500 − 2,500). Domestic consumers buy less of the product at higher prices. Even so, the domestic industry is happy, because its prices and output have risen. The government, meanwhile, collects revenues equal to $100,000 ($100 × 1,000), the shaded area in Figure 6. These revenues can be significant: In the 1800s, tariffs were the federal government’s dominant form of revenue. It is only in the last century that the federal government has come to rely more on other sources of revenue, including taxes on income, sales, and property.

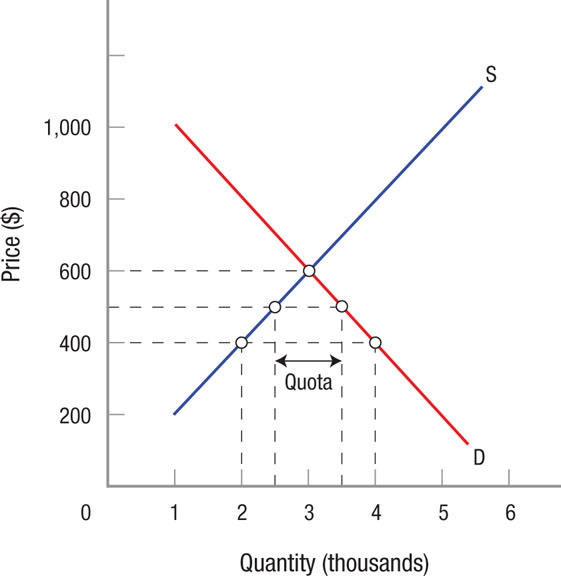

quota A government set limit on the quantity of imports into a country.

383

Figure 7 shows the effects of a quota. They are similar to what we saw in Figure 6, except that the government restricts the quantity of imports into the country to 1,000 units. Imports fall to the quota level, and consumers again lose, because they must pay higher prices for less output. Producers and their employees gain as prices and employment in the domestic industry rise. For a quota, however, the government does not collect revenue. Then who gets this revenue? The foreign exporting company gets it in the form of higher prices for its products. This explains why governments prefer tariffs over quotas.

The United States imposed quotas on Japanese automobiles in the 1980s. The primary effect of these quotas was initially to raise the minimum standard equipment and price dramatically for some Japanese cars and ultimately to increase the number of Japanese cars made in American factories. If a firm is limited in the number of vehicles it can sell, why not sell higher priced ones where the profit margins are higher? The Toyota Land Cruiser, for instance, was originally a bare-bones SUV selling for under $15,000. With quotas, this vehicle was transformed into a luxury behemoth with all the bells and whistles standard. Although quotas on Japanese automobiles have long expired, Japanese automakers continue to produce a wide array of luxury automobiles today.

One problem with tariffs and quotas is that when they are imposed, large numbers of consumers pay just a small amount more for the targeted products. Few consumers are willing to spend time and effort lobbying Congress to end or forestall these trade barriers from being introduced. Producers, however, are often few in number, and they stand to gain tremendously from such trade barriers. It is no wonder that such firms have large lobbying budgets and provide campaign contributions to political candidates.

384

Do Foreign Trade Zones Help or Hurt American Consumers and Workers?

Driving through the gates of the Cartago Zona Franca in Costa Rica, one encounters a remarkable sight in a historic Central American town: large factories adorned with the names of large American companies in industries including pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, medical supplies, and household products. What are these companies doing in Costa Rica, and why did they choose to locate within this small gated compound?

In Cartago, as well as in other cities throughout the world, clusters of multinational companies engage in manufacturing activities. These companies are taking advantage of the benefits offered by foreign trade zones, also commonly known as free trade zones or export processing zones.

A foreign trade zone is a designated area in a country where foreign companies can import inputs, without tariffs, to be used for product assembly by local workers who are often paid a fraction of what equivalent workers would be paid in the company’s home country. By operating in a foreign trade zone, all inputs coming into a country are exempted from tariffs as long as the finished products (with some exceptions) are then exported from the country. Further, companies are often exempted from other taxes levied by the government.

Countries such as China, the Philippines, and Costa Rica establish foreign trade zones to attract foreign investment, which creates well-paying jobs relative to wages paid by domestic companies. Countries with high literacy rates, like Costa Rica, are especially attractive because their workers can perform semiskilled tasks such as assembling electronic and computer products or handling customer service calls. Foreign trade zones also are prevalent along border towns, such as those in Mexico, where easy transportation to and from the United States allows inputs and products to flow rapidly.

Although companies operating in foreign trade zones benefit from lower production costs and the host country benefits from jobs created, not everyone is in favor of foreign trade zones. Various unions in the United States view foreign trade zones as facilitating the offshoring of American jobs. Offshoring (also commonly referred to as outsourcing) occurs when part of the production process (typically the labor-intensive portions) is sent to countries with lower input costs.

What may be surprising, however, is that foreign trade zones and offshoring are not one-way streets. Foreign trade zones are not limited to developing countries with low labor costs. The United States has many foreign trade zones established for the same purpose: to attract foreign companies to invest in manufacturing plants. Although American labor costs are high, they often are lower than wages in European countries or in Japan. By moving production to the United States, European and Japanese companies produce goods such as cars while enjoying the same tax benefits described earlier by American companies operating abroad.

Most of the arguments against offshoring are based on anecdotal evidence—a plant closing here, a closing there, and so on. But in the mid-2000s, the Bureau of Labor Statistics developed a survey to quantify the levels of both offshoring and inshoring (the flow of jobs to the United States by firms from other countries). In the year 2012, statistics showed that the net effect was roughly equal, that almost as many jobs were created by foreign companies in the United States as jobs lost from American companies moving production facilities overseas.

As we have seen, there are both winners and losers in trade. But in general, economists found that there is a net increase in income to U.S. residents from offshoring. When all impacts are considered, including savings to consumers from lower product costs, imports of U.S. goods by foreigners, profits to U.S. affiliates, and the value of labor reemployed, the benefits tend to outweigh the costs. Clearly, those who lose their jobs suffer. But with a policy to provide training to displaced workers, the savings from offshoring can lead to greater investment and growth in the long run.

THE TERMS OF TRADE

385

- The terms of trade are determined by the ratio of the price of exported goods to the price of imported goods.

- The terms of trade are set by the markets in each country and by exports and imports that eventually equalize the prices.

- Trade leads to winners and losers in each country and in each market.

- Trade restrictions vary from subsidies to domestic firms to government bans on the import of foreign products.

- Tariffs are taxes on imports that protect domestic producers and generate revenue for the government.

- Quotas represent restrictions on the volume of particular imports that can come into a country. Quotas do not generate revenue for governments and are infrequently used.

QUESTION: When the government imposes a quota on foreign trucks, who benefits and who loses?

When a quota is imposed, the first beneficiary is the domestic industry. Competition from foreign competition is limited. If the market is important enough (automobiles), the foreign companies build new plants in the United States and compete as if they are domestic firms. A second beneficiary is foreign competitors, in that they can increase the price or complexity of their products and increase their margins. Losers are consumers and, to some extent, the government, because a tariff could have accomplished the same reduction in imports and the government would have collected some revenue.