Exchange Rates

As we saw in the chapter opening, if you wish to go abroad or to buy a product directly from a foreign firm, you need to exchange dollars for foreign currency. Today, credit cards automatically convert currencies for you, making the transaction more convenient. This conversion does not, however, alter the transaction’s underlying structure.

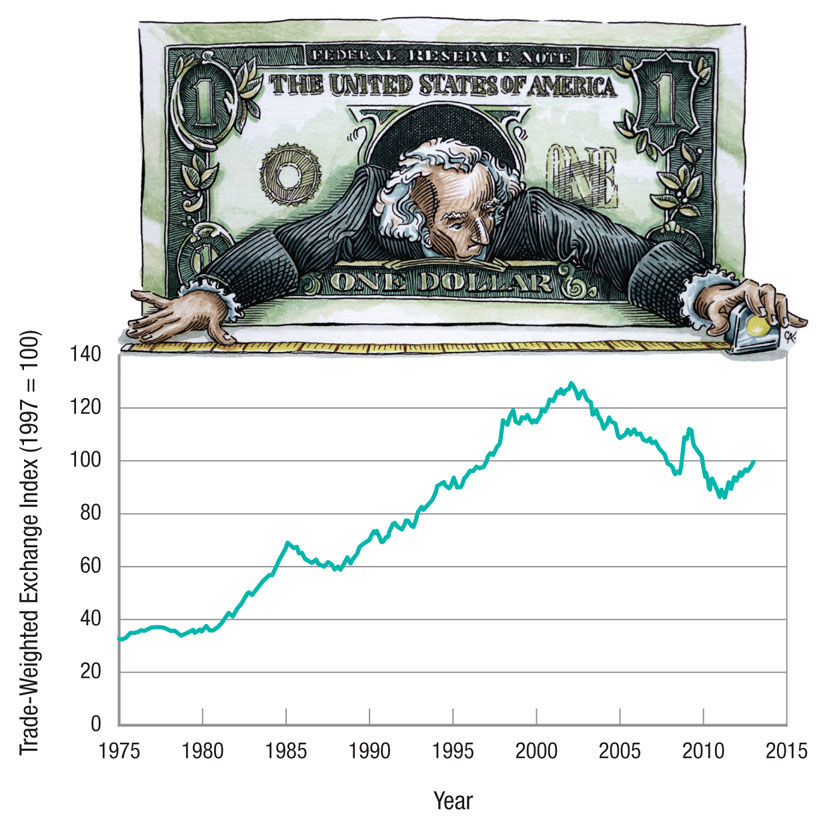

When you decide to travel abroad, the value of the dollar compared to the currency where you are going determines how expensive your trip will be. Figure 1 shows the trade-weighted exchange index value of the dollar compared to a wide range of currencies. The value of the dollar has generally been slowly rising until the early part of this century. This section looks at the issues of exchange rates and their determination.

FIGURE 1

The Value of the Dollar The trade-weighted exchange index, a weighted average of the foreign exchange value of the dollar against a broad group of U.S. trading partners, is shown. Generally, the value of the dollar rose between 1975 and the early 2000s. After that, rising deficits and low interest rates put downward pressure on the dollar, although it has risen again in recent years.

Defining Exchange Rates

exchange rate The rate at which one currency can be exchanged for another, or just the price of one currency for another.

The exchange rate is defined as the rate at which one currency, such as U.S. dollars, can be exchanged for another, such as British pounds. The exchange rate is nothing more than the price of one currency for another. Table 2 below shows exchange rates for selected countries for a specific date (October 1, 2013), as found on the Web site xe.com. Exchange rates can be quoted in one of two ways: (1) the price (in domestic currency) of one unit of foreign currency, or (2) the number of units of a foreign currency required to purchase one unit of domestic currency. As Table 2 illustrates, exchange rates are often listed from both perspectives.

Nominal Exchange Rates According to Table 2, 1 British pound will buy 1.60 dollars. Equivalently, 1 dollar will purchase 0.62 pound. These numbers are reciprocal measures of each other (1 ÷ 1.60 = 0.62).

nominal exchange rate The rate at which one currency can be exchanged for another.

real exchange rate The price of one country’s currency for another when the price levels of both countries are taken into account; important when inflation is an issue in one country; it is equal to the nominal exchange rate multiplied by the ratio of the price levels of the two countries.

Real Exchange Rates A nominal exchange rate is the price of one country’s currency for another. The real exchange rate takes the price levels of both countries into account. Real exchange rates become important when inflation is an issue in one country. The real exchange rate between two countries is defined as

er = en × (Pd/Pf)

where er is the real exchange rate, en is the nominal exchange rate, Pd is the domestic price level, and Pf is the foreign price level.

The real exchange rate is the nominal exchange rate multiplied by the ratio of the price levels of the two countries. In plain words, the real exchange rate tells us how many units of the foreign good can be obtained for the price of one unit of that good domestically. The higher this number, the cheaper the good abroad becomes. If the real exchange rate is greater than 1, prices abroad are lower than at home. In a broad sense, the real exchange rate may be viewed as a measure of the price competitiveness between the two countries. When prices rise in one country, its products are not as competitive in world markets.

Let us take British and American cars as an example. Assume that Britain suffers significant inflation, which pushes the price of Land Rovers up by 15% in Britain. The United States, meanwhile, suffers no such inflation of its price level. If the dollar-to-pound exchange rate remains constant for the moment, the price of Land Rovers in the U.S. market will climb, while domestic auto prices remain constant.

Now Land Rovers are not as competitive as before, resulting in fewer sales. Note, however, that the resulting reduction in U.S. purchases of British cars and other items will reduce the demand for British pounds. This puts downward pressure on the pound, reducing its exchange value and restoring some competitiveness. Markets do adjust! We will look at this issue in more detail later in the chapter.

purchasing power parity The rate of exchange that allows a specific amount of currency in one country to purchase the same quantity of goods in another country.

Purchasing Power Parity Purchasing power parity (PPP) is the rate of exchange that allows a specific amount of currency in one country to purchase the same quantity of goods in another country. Absolute PPP would mean that nominal exchange rates equaled the same purchasing power in each country. As a result, the real exchange rate would be equal to 1. For example, PPP would exist if $4 bought a meal in the United States, and the same $4 converted to British pounds (about £2.5) bought the same meal in London.

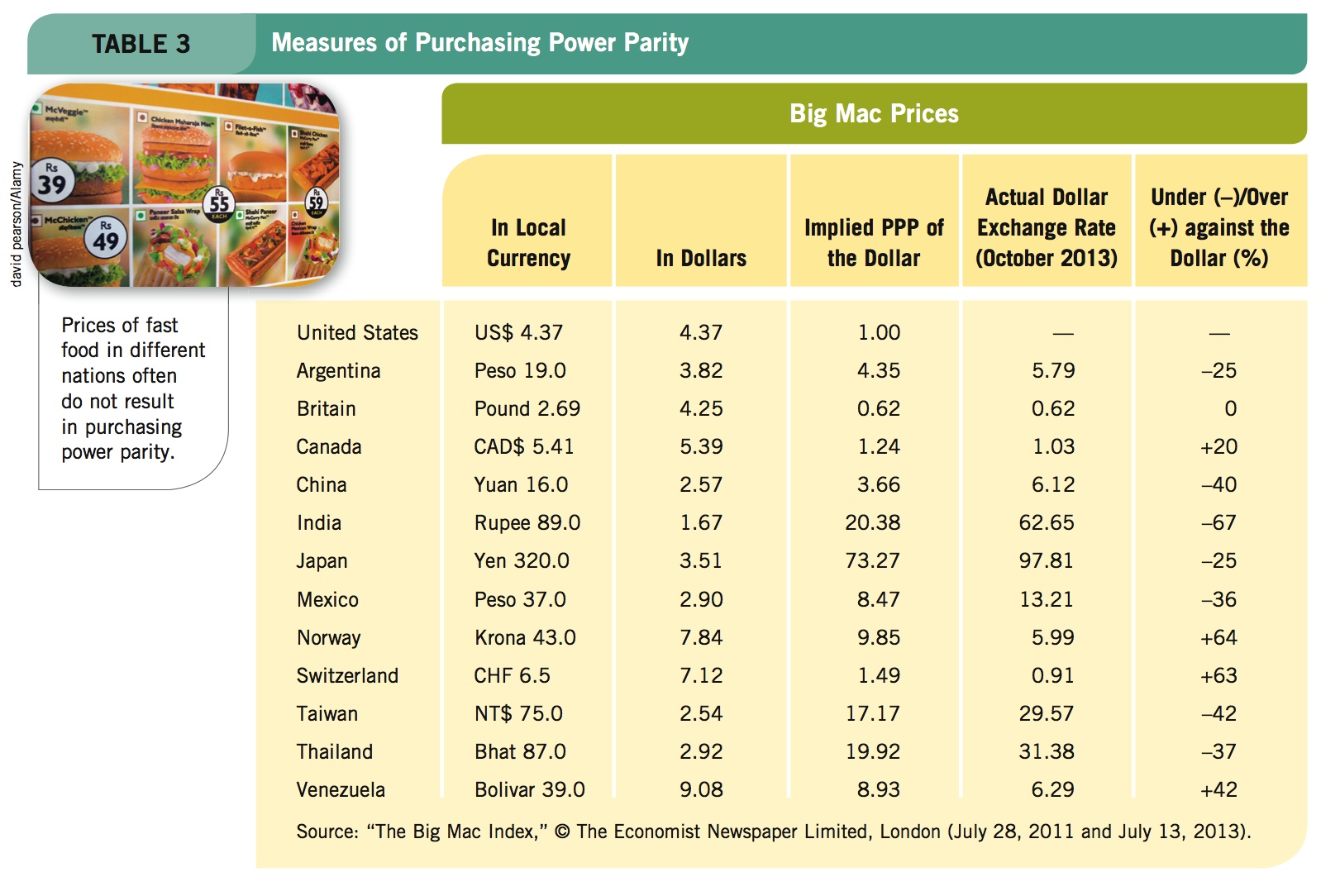

If you have traveled abroad, you know that PPP is not absolute. Some countries, such as India and Thailand, are known as inexpensive countries, while others, such as Norway and Switzerland, can be expensive. The Economist annually publishes a “Big Mac Index,” a lighthearted attempt to capture the notion of PPP.

ACE STOCK LIMITED/Alamy

Table 3 presents some recent estimates of PPP and the Big Mac Index. It also shows the PPP implied by the relative cost of Big Macs, along with the actual exchange rate. When comparing these two, we get an approximate over- or understating of the exchange rate. Keep in mind that the cost of a McDonald’s Big Mac may be influenced by many unique local factors (trade barriers on beef, customs duties, taxes, competition), and therefore it may not reflect real PPP. Also, in some countries where beef is not consumed, chicken patties are substituted; and in still other countries, vegetarian patties are used.

Although not perfect, changes in the Big Mac Index often are reflective of movements in true PPP, given that simultaneous changes in several of the factors that distort the index often reflect real changes in the economy.

Exchange Rate Determination

We have seen that people and institutions have two primary reasons for wanting foreign currency. The first is to purchase goods and services and conduct other transactions under the current account. The second is to purchase foreign investments under the capital account. These transactions create a demand for foreign currency and give rise to a supply of domestic currency available for foreign exchange.

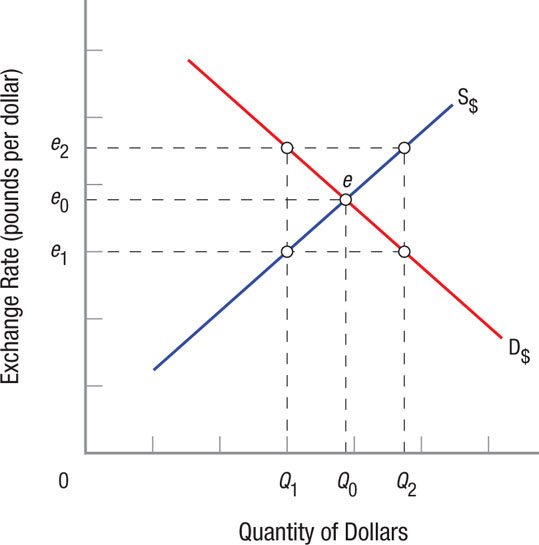

A Market for Foreign Exchange Figure 2 shows a representative market for foreign exchange. The horizontal axis measures the quantity of dollars available for foreign exchange, and the vertical axis measures the exchange rate in British pounds per U.S. dollar. The demand for dollars as foreign exchange is downward sloping; as the exchange rate falls, U.S. products become more attractive, and more dollars are desired.

FIGURE 2

The Foreign Exchange Market for Dollars A market for foreign exchange is shown here. The horizontal axis measures the quantity of dollars available for foreign exchange, and the vertical axis measures the exchange rate in pounds per dollar. If exchange rates are fully flexible and the exchange rate is initially e1, there is excess demand for dollars: Q2 minus Q1. The dollar will appreciate and the exchange rate will move to e0. Alternatively, if the exchange rate is initially e2, there is an excess supply of dollars. Because there are more dollars being offered than demanded, the dollar will depreciate. Eventually, the market will settle into an exchange rate of e0, where precisely the quantity of dollars supplied is the quantity demanded.

Suppose, for example, that the exchange rate at first is $1 = £1 and that the U.S. game company Electronic Arts manufactures and sells its games at home and in Britain for $50 (£50). Then suppose that the dollar depreciates by 50%, such that $1.00 = £0.50. If the dollar price of a game remains at $50 in the United States, the pound price of games in Britain will fall to £25 because of the reduction in the exchange rate. This reduction will increase the sales of games in Britain and increase the quantity of dollars British consumers need for foreign exchange.

The supply of dollars available for foreign exchange reflects the demand for pounds, because to purchase pounds, U.S. firms or individuals must supply dollars. Not surprisingly, the supply curve for dollars is positively sloped. If the dollar were to appreciate, say, moving to $1 = £2, British goods bought in the United States would look attractive because their dollar price would be cut in half. As Americans purchased more British goods, the demand for pounds would grow, and the quantity of dollars supplied to the foreign exchange market would increase.

appreciation (currency) When the value of a currency rises relative to other currencies.

Flexible Exchange Rates Assume that exchange rates are fully flexible, such that the market determines the prevailing exchange rate, and that the exchange rate in Figure 2 is initially e1. At this exchange rate, there is an excess demand for dollars because quantity Q2 is demanded but only Q1 is supplied. The dollar will appreciate, or rise in value relative to other currencies, and the exchange rate will move in the direction of e0 (more pounds are required to purchase a dollar). As the dollar appreciates, it becomes more expensive for British consumers, thus reducing the demand for U.S. exports. Because of the appreciating dollar, British imports are more attractive for U.S. consumers, increasing U.S. imports. These forces work to move the exchange rate to e0, closing the gap between Q2 and Q1.

depreciation (currency) When the value of a currency falls relative to other currencies.

Alternatively, if the exchange rate begins at e2, there will be an excess supply of dollars. Because more dollars are being offered than demanded, the value of dollars relative to British pounds will decline, or depreciate. American goods are now more attractive in Britain, increasing American exports and the demand for dollars, while British goods become more expensive for American consumers. Eventually, the market will settle into an exchange rate of e0, at which precisely the quantity of dollars supplied is the quantity demanded.

Currency Appreciation and Depreciation A currency appreciates when its value rises relative to other currencies and depreciates when its value falls. This concept is clear enough in theory, but it can get confusing when we start looking at charts or tables that show exchange rates. The key is to be certain of which currency is being used to measure the value of other currencies. Does the table you are looking at show the pound price of the dollar or the dollar price of the pound?

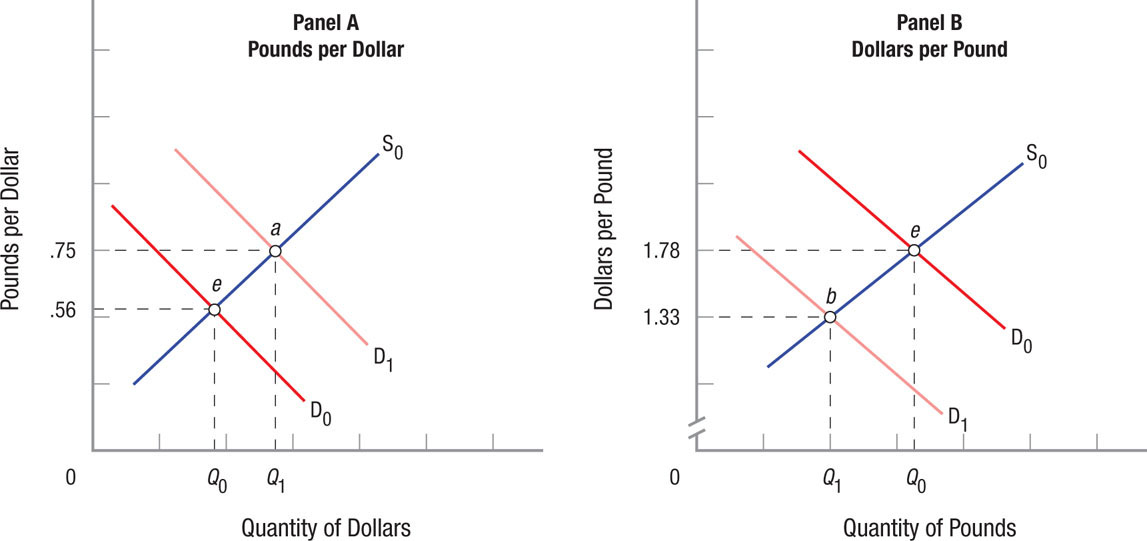

Figure 3 below shows the exchange markets for dollars and pounds. Panel A shows the market for dollars, where the price of dollars is denominated in pounds (£/$), just as in Figure 2. This market is in equilibrium at £0.56 per dollar (point e). Panel B shows the equivalent market for pounds; it is in equilibrium at $1.78 per pound (again at point e). Note that 1 ÷ 0.56 = 1.78, therefore panels A and B represent the same information, just from different viewpoints.

FIGURE 3

The Foreign Exchange Market Data for dollars and pounds are graphically represented here. Panel A shows a market for dollars in which the price of dollars is denominated in pounds (£/$). In panel A, the market is in equilibrium at £0.56 per dollar (point e). Panel B shows the equivalent market for pounds in equilibrium at $1.78 per pound (again at point e). A rise in the demand for dollars means that the dollar appreciates to £0.75 per dollar (point a in panel A). Panel B shows that the corresponding decline in demand for pounds (from D0 to D1) leads to a depreciation of the pound as the exchange rate falls from $1.78 to $1.33 per pound (point b).Note that a depreciating pound in panel B indicates a decline in the exchange rate, but this simultaneously represents an appreciating dollar. Thus, graphs can be viewed as reflecting either appreciation or depreciation, depending on which currency is being used to establish the point of view.

Assume that there is a rise in the demand for dollars. In panel A, the dollar appreciates to £0.75 per dollar (point a), thus leading to a rise in the exchange rate. In panel B, the corresponding decline in demand for pounds (from D0 to D1) leads to a depreciation of the pound and a fall in the exchange rate from $1.78 to $1.33 per pound (point b). Notice that the pound’s depreciation in panel B produces a decline in the exchange rate, but this decline simultaneously results in appreciation of the dollar. These graphs could be viewed as showing either an appreciation or a depreciation, depending on which currency represents your point of view.

For our purposes, we will try to use figures that show the exchange rate rising when the focus currency appreciates. Still, you need to be aware that exchange rates can be represented in two different ways. Exchange rate graphs are difficult and sometimes confusing, therefore you will need to think through each graph you encounter.

Determinants of Exchange Rates What sort of conditions will cause currencies to appreciate or depreciate? First, a change in our tastes and preferences as consumers for foreign goods will result in currency appreciation or depreciation. For example, if we desire to purchase more foreign goods, this will lead to an increase in the demand for foreign currency and result in the depreciation of the dollar.

Second, if our income growth exceeds that of other countries, our demand for imports will grow faster relative to the growth of other nations. This will lead again to an increase in demand for foreign currency, resulting in the depreciation of the dollar.

Third, rising inflation in the United States relative to foreign nations makes our goods and services relatively more expensive overseas and foreign goods more attractive here at home. This results in growing imports, reduced exports, and again leads to a depreciation of the dollar.

Fourth, falling interest rates in the United States relative to foreign countries makes financial investment in the United States less attractive. This reduces the demand for dollars, leading once again to a depreciation of the dollar.

Note that if we reverse these stories in each case, the dollar will appreciate.

Exchange Rates and the Current Account

As we have already seen, the current account includes payments for imports and exports. Also included are changes in income flowing into and out of the country. In this section, we focus on the effect that changes in real exchange rates have on both of these components of the current account. We will assume that import and export demands are highly elastic as prices change due to changes in the exchange rate.

Changes in Inflation Rates Let’s assume that inflation heats up in Britain, such that the British price level rises relative to U.S. prices, or the dollar appreciates relative to the pound. Production costs rise in Britain, therefore British goods are more expensive. American goods appear more attractive to British consumers, therefore exports of American goods rise, improving the U.S. current account. American consumers purchase more domestic goods and fewer British imports because of rising British prices, further improving the American current account. The opposite is true for Britain: British imports rise and exports fall, hurting the British current account.

These results are dependent on our assumption that import and export demands are highly elastic with real exchange rates. Thus, when exchange rates change, exports and imports will change proportionally more than the change in exchange rates.

Changes in Domestic Disposable Income If domestic disposable income rises, U.S. consumers will have more money to spend, and given existing exchange rates, imports will rise because some of this increased consumption will go to foreign products. As a result, the current account will worsen as imports rise. The opposite occurs when domestic income falls.

Exchange Rates and the Capital Account

The capital account summarizes flows of money or capital into and out of U.S. assets. Each day, foreign individuals, companies, and governments put billions of dollars into Treasury bonds, U.S. stocks, companies, and real estate. Today, foreign and domestic assets are available to investors. Foreign investment possibilities include direct investment in projects undertaken by multinational firms, the sale and purchase of foreign stocks and bonds, and the short-term movement of assets in foreign bank accounts.

Because these transactions all involve capital, investors must balance their risks and returns. Two factors essentially incorporate both risk and return for international assets: interest rates and expected changes in exchange rates.

Interest Rate Changes If the exchange rate is assumed to be constant, and the assets of two countries are perfectly substitutable, then an interest rate rise in one country will cause capital to flow into it from the other country. For example, a rise in interest rates in the United States will cause capital to flow from Britain, where interest rates have not changed, into the United States, where investors can earn a higher rate of return on their investments. Because the assets of both countries are assumed to be perfectly substitutable, this flow will continue until the interest rates (r) in Britain and the United States are equal, or

rUS = rUK

Everything else being equal, we can expect capital to flow in the direction of the country that offers the highest interest rate, and thus, the highest return on capital. But “everything else” is rarely equal.

Expected Exchange Rate Changes Suppose that the exchange rate for U.S. currency is expected to appreciate (Δε > 0). The relationship between the interest rates in the United States and Britain becomes

rUS = rUK − Δε

Investors demand a higher return in Britain to offset the expected depreciation of the British pound relative to the U.S. dollar. Unless interest rates rise in Britain, capital will flow out of Britain and into the United States until U.S. interest rates fall enough to offset the expected appreciation of the dollar.

If capital is not perfectly mobile and substitutable between two countries, a risk premium can be added to the relationship just described; thus,

rUS = rUK − Δε + x

where x is the risk premium. Expected exchange rate changes and risk premium changes can produce enduring interest rate differentials between two countries.

If the dollar falls relative to the yen, the euro, and the British pound, this is a sign that foreign investors were not as enthusiastic about U.S. investments. Low interest rates and high deficits may have convinced foreign investors that it was not a good time to invest in the United States. The United States is more dependent on foreign capital than ever before. Today, about half of U.S. Treasury debt held by the public is held by foreigners. Changes in inflation, interest rates, and expectations about exchange rates are important.

Exchange Rates and Aggregate Supply and Demand

How do changes in nominal exchange rates affect aggregate demand and aggregate supply? A change in nominal exchange rates will affect imports and exports. Consider what happens, for example, when the exchange rate for the dollar depreciates. The dollar is weaker, and thus the pound (or any other currency) will buy more dollars. American products become more attractive in foreign markets, therefore American exports increase and aggregate demand expands. Yet, because some inputs into the production process may be imported (raw materials, computer programming services, or call answering services), input costs will rise, causing aggregate supply to contract.

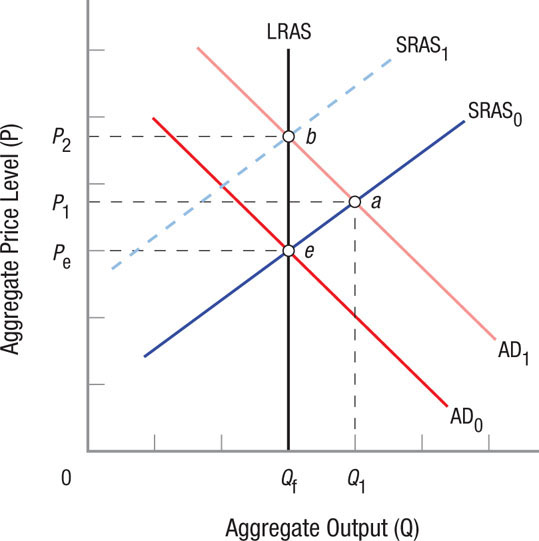

Let us take a more detailed look at this process by considering Figure 4. Assume that the economy begins in equilibrium at point e, with full employment output Qf and the price level at Pe. As the dollar depreciates, this will spur an increase in exports, thus shifting aggregate demand from AD0 to AD1 and raising prices to P1 in the short run. Initially, output climbs to Q1, but because some of the economy’s inputs are imported, short-run aggregate supply will decline, mitigating this rise in output. In the short run, the economy will expand beyond Qf, and prices will rise.

FIGURE 4

Exchange Rates and Aggregate Demand and Supply Assume that the economy initially begins in equilibrium at point e, with full employment output Qf and the price level at Pe. Assume that the dollar depreciates. This will increase exports, shifting aggregate demand from AD0 to AD1 and raising prices to P1 and output to Q1 in the short run. In the long run, short-run aggregate supply will shift from SRAS0 to SRAS1, as workers readjust their wage demands in the long run, thus moving the economy to point b. As the economy adjusts to a higher price level, the benefits from currency depreciation are greatly reduced.

In the longer term, as domestic prices rise, workers will realize that their real wages do not purchase as much as they did before, because import prices are higher. As a result, workers will start demanding higher wages just to bring them back to where they were originally. This shifts short-run aggregate supply from SRAS0 to SRAS1, thereby moving the economy from point a in the short run to point b in the long run. As the economy adjusts to a higher price level, the original benefits accruing from currency depreciation will be greatly reduced.

Currency depreciation works because imports become more expensive and exports less so. When this happens, consumer income no longer goes as far, because the price of domestic goods does not change, but the cost of imports rises. In countries where imports form a substantial part of household spending, major depreciations in the national currency can produce significant declines in standards of living. Such depreciations (or devaluations) have occasioned strikes and, in some cases, even street riots; examples in recent decades include such actions in Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, and Indonesia.

Would a Stronger Chinese Yuan Be Good for Americans?

Much discussion in recent years has focused on the accusation that the Chinese government manipulated the value of its currency, the yuan. What exactly did China do?

When Americans purchase goods from China (and we purchase a whole lot of goods), normally dollars must be exchanged for yuan to pay for these goods. Factories in China need to pay their workers in yuan so that their workers can pay their rent and buy groceries. When dollars are exchanged for yuan, demand for yuan increases, which raises its value. Therefore, the yuan should appreciate against the dollar.

When the yuan appreciates, it takes more dollars to obtain the same amount of yuan as before. Therefore, goods made in China, from toys you buy for your nephews and nieces to shoes, clothes, and electronics you buy for yourself, become more expensive.

To prevent the prices of China’s exports from rising too much in the United States, the Chinese government bought up many of these dollars flowing into China, preventing them from being sold on the foreign exchange market. By holding U.S. dollars, the dollar value is kept from falling. In 2013, China held over 1 trillion in U.S. dollars.

Who benefited from this policy and who lost out? The actions by the Chinese government to prevent the yuan from appreciating keeps prices of Chinesemade goods low for ordinary American consumers, especially benefiting those with limited budgets. Thanks, China, for helping the U.S. consumer.

Who lost out? China’s policy made it harder for American (and other non Chinese) companies to compete against Chinese imports.

If the winners from this policy are American consumers and the losers are American businesses and their workers, policymakers are faced with quite a dilemma. Pressuring the Chinese to let its currency appreciate might be good for American companies, though it will lead to higher prices for many goods that we buy. Are we ready to see the cost of this policy come out of our pockets? Many Americans would be reluctant to support such an outcome, because it would have a similar effect as an increase in taxes or inflation. Both reduce the purchasing power of our income and savings.

Indeed, you can see that the debate about currency manipulation goes beyond whether one side is playing by the rules. Sometimes, fairness can be a costly proposition.

What are the implications of all this for policymakers? First, a currency depreciation or devaluation can, after a period, lead to inflation. In most cases, however, the causation probably goes the other way: Macroeconomic policies or economic events force currency depreciations.

Trade balances usually improve with an exchange rate depreciation. Policymakers can get improved current account balances without inflation by pursuing devaluation first, then pursuing fiscal contraction (reducing government spending or increasing taxes), and finally moving the economy back to point e in Figure 4. But here again, the real long-run benefit is more stable monetary and fiscal policies.

EXCHANGE RATES

- Nominal exchange rates define the rate at which one currency can be exchanged for another.

- Real exchange rates are the nominal exchange rates multiplied by the ratio of the price levels of the two countries.

- Purchasing power parity (PPP) is a rate of exchange that permits a given level of currency to purchase the same amount of goods and services in another country.

- A currency appreciates when its value rises relative to other currencies. Currency depreciation causes a currency to lose value relative to others.

- Inflation causes depreciation of a country’s currency, worsening its current account. Rising domestic income typically results in rising imports and a deteriorating current account.

- Rising interest rates cause capital to flow into the country with the higher interest rate, and expectations about a future currency appreciation or depreciation affect the capital account.

- Currency appreciation and depreciation have an effect on aggregate supply and demand. For example, currency depreciation expands aggregate demand as exports increase, but some (now higher-priced) imported inputs are inputs into production, reducing aggregate supply.

QUESTION: Cities along the U.S.–Canadian border, such as Vancouver, Niagara Falls, Detroit, and Buffalo, receive a substantial number of day visitors. For example, Americans might cross the border into Niagara Falls for a day of sightseeing, while Canadians might cross the border into Detroit to shop. Suppose that the value of the Canadian dollar appreciates against the U.S. dollar. How does this change affect tourism, businesses that depend on day-trippers, and the current account of the United States and Canada?

When the Canadian dollar appreciates against the U.S. dollar, Canadian tourists visiting the United States receive more U.S. dollars for each Canadian dollar. Therefore, purchases by Canadian tourists in the United States become cheaper. As a result, demand rises, helping American businesses that depend on Canadian tourists. Also, the increased flow of money into the United States helps improve the U.S. current account. Meanwhile, the opposite occurs for American tourists to Canada, who find it more expensive to visit Canada. Because the higher cost of travel will discourage some Americans from visiting Canada, Canadian businesses, such as those in Niagara Falls, will suffer. Also, the reduction in money being spent by Americans in Canada will hurt Canada’s current account.