Specialization, Comparative Advantage, and Trade

As we have seen, economics is all about voluntary production and exchange. People and nations do business with one another because all expect to gain from the transactions. Centuries ago, European merchants ventured to the Far East to ply the lucrative spice trade. These days, American consumers buy wines from Italy, cars from Japan, electronics from Korea, and millions of other products from countries around the world.

Many people assume that trade between nations is a zero-sum game—a game in which, for one party to gain, another party must lose. This is how poker works. If one player walks away from the table a winner, someone else must have lost. But this is not how voluntary trade works. Voluntary trade is a positive-sum game: Both parties to a transaction score positive gains. After all, who would voluntarily enter into an exchange if he or she did not believe there was some gain from it? To understand how all parties to an exchange (whether individuals or nations) can gain from it, we need to consider the concept of comparative advantage developed by David Ricardo roughly 200 years ago, and how this concept differs from the concept of absolute advantage.

DAVID RICARDO (1772–1823)

David Ricardo’s rigorous, dispassionate evaluation of economic principles influenced generations of theorists, including such vastly different thinkers as John Stuart Mill and Karl Marx. Ricardo was born in London as the third of 17 children. At age 14 he joined his father’s trading business on the London Stock Exchange. At 21, he started his own brokerage and within five years had amassed a small fortune.

While vacationing in Bath, England, he chanced upon a copy of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, and decided to devote his energies to studying economics and writing. He once wrote to his lifelong friend Thomas Malthus (another prominent economist of the time) that he was “thankful for the miserable English climate because it kept him at his desk writing.” Ricardo and Malthus corresponded on a regular basis, and their exchanges led to the development of many economic concepts still used today.

Later, as a member of the British Parliament, Ricardo was an outspoken critic of the 1815 Corn Laws, which placed high tariffs on imported grain to protect British landowners. Ricardo was a strong advocate of free trade, and his writings reflected this view. His theory of “comparative advantage” suggested that countries would mutually benefit from trade by specializing in export goods they could produce at a lower opportunity cost than another country. His classic example was trade in cloth and wine between Britain and Portugal.

Ricardo died in 1823 of an ear infection, leaving an enduring legacy of classical (pre-1930s) economic analysis.

Sources: E. Ray Canterbery, A Brief History of Economics (New Jersey: World Scientific), 2001; Howard Marshall, The Great Economists: A History of Economic Thought (New York: Pitman Publishing), 1967; Steven Pressman, Fifty Major Economists, 2nd ed., (New York: Routledge), 2006.

Absolute and Comparative Advantage

absolute advantage One country can produce more of a good than another country.

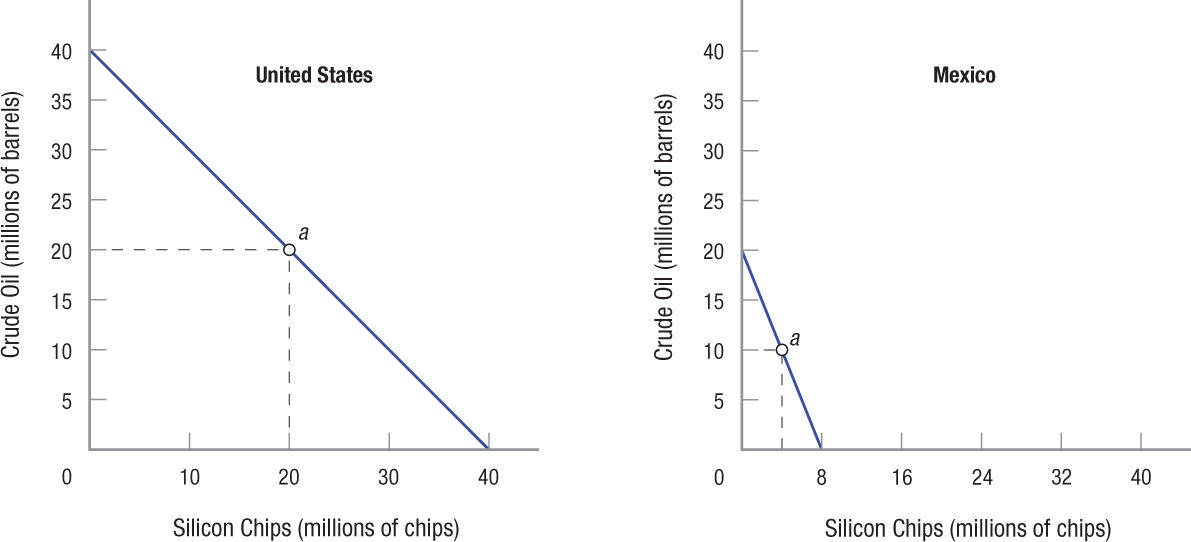

Figure 7 shows hypothetical production possibilities curves for the United States and Mexico. To simplify the analysis, we assume that opportunity costs are constant (PPFs are straight lines); however, the same analysis applies to PPFs with increasing opportunity costs. Both countries are assumed to produce only crude oil and silicon chips. Given the PPFs in Figure 7, the United States has an absolute advantage over Mexico in producing both products. An absolute advantage exists when one country can produce more of a good than another country. In this instance, the United States can produce 2 times more oil (40 million versus 20 million barrels) and 5 times as many silicon chips (40 million versus 8 million chips) as Mexico.

FIGURE 7

Production Possibilities for the United States and Mexico One country has an absolute advantage if it can produce more of a good than another country. In this case, the United States has an absolute advantage over Mexico in producing both silicon chips and crude oil—it can produce more of both goods than Mexico can. Even so, Mexico has a comparative advantage over the United States in producing oil, since it can increase its output of oil at a lower opportunity cost than can the United States. This comparative advantage leads to gains for both countries from specialization and trade.

comparative advantage One country has a lower opportunity cost of producing a good than another country.

At first glance you might wonder why the United States would even consider trading with Mexico. The United States has so much more production capacity than Mexico, so why wouldn’t it just produce all of its own crude oil and silicon chips? The answer lies in comparative advantage.

One country has a comparative advantage in producing a good if its opportunity cost to produce that good is lower than the other country’s. We can calculate each country’s opportunity cost for each good using the production possibility frontiers in Figure 7.

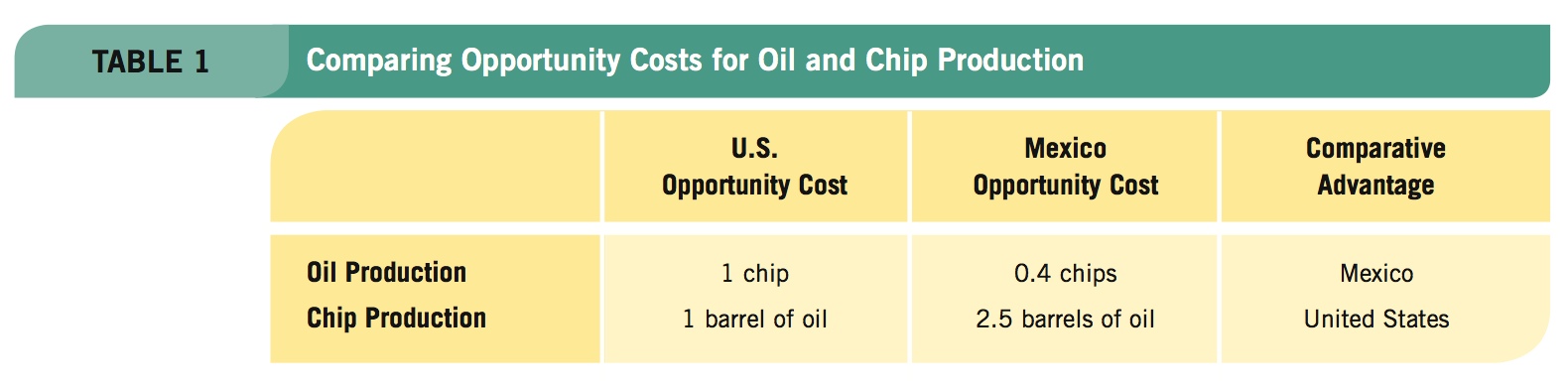

If the United States uses all of its resources efficiently, it can produce a maximum of 40 million barrels of oil or 40 million silicon chips. It can also produce some of both goods, though clearly not 40 million of each, because in order to produce more of one good, it must reduce production of another (its opportunity cost). Because the PPF is linear, the tradeoff between oil and chips is constant. For the United States, it can substitute 1 million barrels of oil for 1 million silicon chips, which means it can produce 20 million barrels of oil and 20 million silicon chips. The opportunity cost for each good is summarized as follows:

- For every barrel of oil the United States produces, it must give up producing one silicon chip.

- For every silicon chip the United States produces, it must give up producing one barrel of oil.

Now let’s look at Mexico. If it uses its resources efficiently, it can produce a maximum of 20 million barrels of oil or 8 million silicon chips. For Mexico, although the tradeoff between goods also is constant, the tradeoff is not one-for-one as in the United States. Because Mexico is better at producing oil than silicon chips, its opportunity cost for each good is as follows:

- For every barrel of oil Mexico produces, it must give up producing 0.4 silicon chips.

- For every silicon chip Mexico produces, it must give up producing 2.5 barrels of oil.

Note that the values of 0.4 and 2.5 are inverses of one another. In other words, 1/0.4 = 2.5, and 1/2.5 = 0.4. This relationship exists when calculating opportunity costs in a two-product economy.

Now that we have determined the opportunity cost of each good in both countries, we can conclude that Mexico has a comparative advantage over the United States in producing oil. This is because Mexico gives up only 0.4 chips for every barrel of oil it produces, while the United States must give up 1 chip. Thus, Mexico’s opportunity cost of producing oil is less than that of the United States, giving Mexico a comparative advantage.

Conversely, the United States has a comparative advantage over Mexico in producing silicon chips: Producing a silicon chip in the United States costs one barrel of oil, whereas the same chip in Mexico costs two-and-a-half barrels of oil. Table 1 summarizes the opportunity costs of each good and which country has the comparative advantage.

Note that each country has a comparative advantage in one good, even though the United States has an absolute advantage in both goods. However, it is comparative advantage that generates gains from trade. These relative costs suggest that the United States should pour its resources into producing silicon chips, while Mexico specializes in crude oil. The two countries can then engage in trade to their mutual benefit. As long as relative production costs differ between countries, specialization and trade can be mutually beneficial, allowing all countries to consume more.

The same idea applies to individuals. Although we have focused on trade between countries, the concept of comparative advantage explains why individuals specialize in a few tasks and then trade with one another. For example, if you are relatively better at understanding economics than your roommate who is on the golf team, you might offer to tutor economics in exchange for golf lessons. Comparative advantage explains all trade: between individuals as well as between countries.

The Gains from Trade

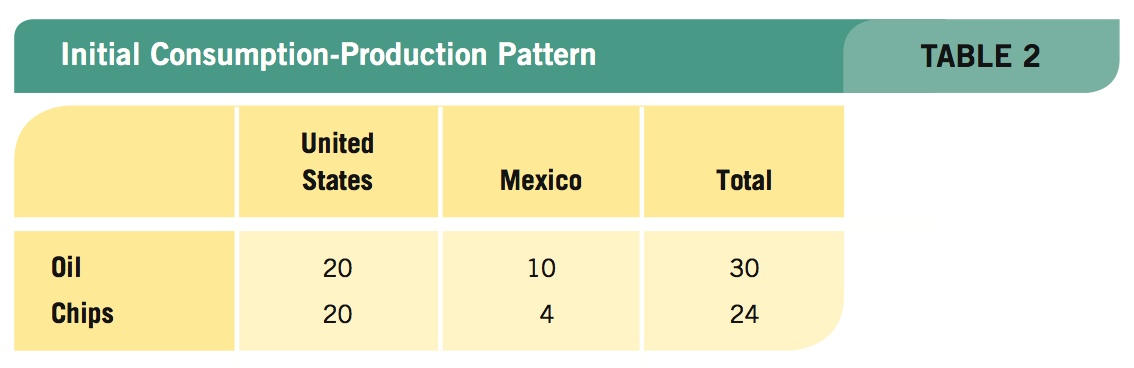

To see how specialization and trade can benefit all trading partners, let’s return to our example in which the United States has the ability to produce more of both goods than Mexico. Assume that each country is at first (before trade) operating at point a in Figure 7. At this point, both countries are producing and consuming only their own output; the United States produces and consumes 20 million barrels of oil and 20 million silicon chips; Mexico, 10 million barrels of oil and 4 million chips. Table 2 summarizes these initial conditions.

Do We Really Specialize in That? Comparative Advantage in the United States and China

What do tofu, edamame, ink, soy sauce, livestock feed, and soy milk have in common? They are all important products commonly made from soybeans. Although direct human consumption of soybeans in the United States is often confined to health food products and food in Asian restaurants, soybeans are much more important to the U.S. economy than most people think. The United States has a comparative advantage in soybean production. It produces and sells more soybeans than any other country, with much of it being sold to China.

How can a rich, technologically advanced country like the United States end up with a comparative advantage in an agricultural good like soybeans? Several factors play a role. First, the United States has an abundance of farmland ideal in climate and soil for soybean production. Second, modern fertilizers and seed technologies have made soybean production a much more innovative industry than in the past, allowing farms to increase soybean yields per acre of land. And third, a strong appetite for soy-based products, particularly in China, has made soybeans a very lucrative industry.

China is the second largest trading partner to the United States after Canada, trading $539 billion worth of goods between the countries in 2011. Yet, the top five U.S. export goods (items sold) and import goods (items bought) with China, listed below, may be surprising.

Although the United States sells a lot of machines and electrical goods to China (mostly specialized machinery and electronics used in factories and research labs), it buys significantly greater amounts of these products from China. In other words, the United States is a net buyer of machinery and electrical goods, industries that include many consumer technology goods we use, such as smartphones, computers, and digital equipment. Besides soybeans, paper pulp and copper are two other resource industries (not listed above) that constitute a large portion of U.S. sales to China.

In sum, specialization and trade are not as simple as they used to be. Products such as computers and electronics that once were the purview of “rich” countries such as the United States are now being manufactured in China and other countries, while improved technology in the agricultural and natural resource industries has given the United States a new form of specialization that would have been unheard of 50 years ago.

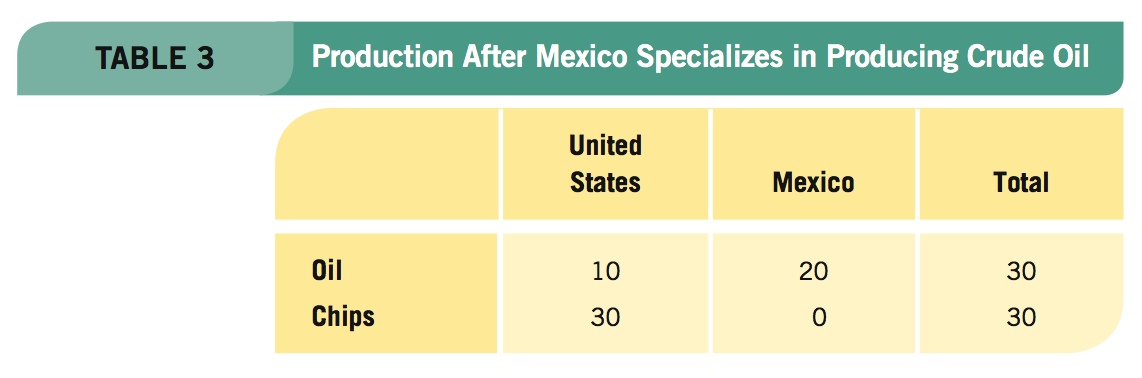

Now assume that Mexico focuses on oil, producing the maximum it can: 20 million barrels. We also assume both countries want to continue consuming 30 million barrels of oil between them. Therefore the United States only needs to produce 10 million barrels of oil because Mexico is now producing 20 million barrels. For the United States, this frees up some resources that can be diverted to producing silicon chips. Because each barrel of oil in the United States costs one chip, reducing oil output by 10 million barrels means that 10 million more chips can be produced.

Table 3 shows each country’s production after Mexico has begun specializing in oil production.

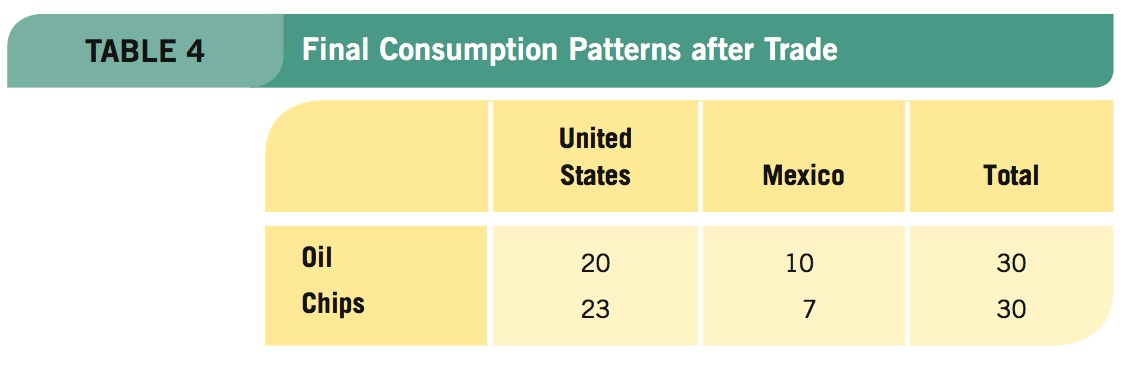

Notice that the combined production of crude oil has remained constant, but the total output of silicon chips has risen by 6 million chips. Assuming that the two countries agree to share the added 6 million chips between them equally, Mexico will now ship 10 million barrels of oil to the United States in exchange for 7 million chips. From the 10 million additional chips the United States produces, Mexico will receive 4 million (its original production) plus 3 million for a total of 7 million, leaving 3 million additional chips for U.S. consumption. The resulting mix of products consumed in each country is shown in Table 4. Clearly, both countries are better off, having engaged in specialized production and trade.

The important point to remember here is that even when one country has an absolute advantage over another, both countries still benefit from trading with one another. In our example, the gains were small, but such gains can grow. As two economies become more equal in size, the benefits of their comparative advantages grow.

Practical Constraints on Trade

Before leaving the subject of international trade and how it contributes to growth in both countries, we should take a moment to note some practical constraints on trade. First, every transaction involves costs, including transportation, communications, and the general costs of doing business. Even so, over the last several decades, transportation and communication costs have been declining all over the world, resulting in growing global trade.

Second, the production possibilities curves for nations are not linear, but rather governed by increasing costs and diminishing returns. Therefore, it is difficult for countries to specialize in producing one product. Complete specialization would be risky, moreover, because the market for a product can always decline, perhaps because the product becomes technologically obsolete. Alternatively, changing weather patterns can wreak havoc on specialized agricultural products, adding further instability to incomes and exports in developing countries.

Finally, although two countries may benefit from trading with one another, expanding this trade may well hurt some industries and individuals within each country. Notably, industries finding themselves at a comparative disadvantage may be forced to scale back production and lay off workers. In such instances, government may need to provide workers with retraining, relocation, and other help to ensure a smooth transition to the new production mix.

When the United States signed the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with Canada and Mexico, many people experienced what we have just been discussing. Some U.S. jobs went south to Mexico because of low production costs. By opening up more markets for U.S. products, however, NAFTA did stimulate economic growth, such that retrained workers may end up with new and better jobs.

SPECIALIZATION, COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE, AND TRADE

- An absolute advantage exists when one country can produce more of some good than another.

- A comparative advantage exists if one country has lower opportunity costs of producing a good than another country. Both countries gain from trade if each focuses on producing those goods with which it has a comparative advantage.

- Voluntary trade is a positive-sum game, because both countries benefit from it.

QUESTION: Why do Hollywood stars (and many other rich individuals)—unlike most people—have full-time personal assistants who manage their personal affairs?

For Hollywood stars and other rich people, the opportunity cost of their time is high. As a result, they hire people at lower cost to do the mundane chores that each of us is accustomed to doing because our time is relatively less valuable.