Chapter Introduction

After studying this chapter you should be able to:

- Understand the concept of elasticity and why percentages are used to measure it.

- Describe the difference between elastic and inelastic demand.

- Compute price elasticities of supply and demand.

- Describe the relationship between total revenue and price elasticity of demand.

- Describe cross elasticity of demand and use this concept to define substitutes and complements.

- Use income elasticity of demand to define normal, inferior, and luxury goods.

- Describe the determinants of the elasticity of demand and the elasticity of supply.

- Use the concept of price elasticity of supply to measure the relationship between changes in product price and quantity supplied.

- Describe the time periods economists use to study elasticity, and describe the variables that companies can change during these periods.

- Describe the relationship between elasticity and the burden and incidence of taxes.

Kris Tripplaar/TRIPPLAAR KRISTOFFER/SIPA/Newscom

At the start of the new millennium, the price of gasoline hovered around $1.50 per gallon—a veritable bargain—with a tankful costing roughly $20. Encouraged by low gas prices and a healthy economy, consumer appetites for bigger vehicles grew, leading to a rapid increase in the market for sport utility vehicles (SUVs) and trucks. Not only did the quantity of large vehicles increase, but the size of SUVs and trucks grew as well. The Hummer H2, Ford Excursion, and Chevy Suburban were all designed for consumers who wanted cars with plenty of space and who were not too concerned about gas prices.

Over the decade that followed, the market for oil and gasoline changed dramatically. Increased tensions in the Middle East along with a huge spike in oil demand from emerging markets such as China and India pushed the prices of a gallon of gas in 2010 to over double what they were a decade ago, and prices have since remained elevated. How did consumers respond to the 100% increase in the average price of gasoline? They reduced consumption by driving less, carpooling, and using public transportation. But by how much did the quantity of gasoline demanded fall?

The rising price of oil not only reduced the amount of gasoline consumers demanded, consumers also changed their preferences for cars. SUVs and trucks became less desirable, while small cars, hybrids, and flex-fuel vehicles became popular. How responsive were consumers in terms of changing their vehicle preferences? Not only did consumers change their buying habits as a result of higher gasoline prices, but producers responded. As prices for oil rose, more companies found it worthwhile to drill for oil, leading countries in Africa, Northern Europe, and even the United States, Canada, and Mexico to increase production. By how much did oil producers respond?

Lastly, as demand for SUVs and trucks fell in response to higher gas prices, car manufacturers responded by reducing the quantity of SUVs and trucks produced. Hummers and Ford Excursions were phased out completely. Producers of vehicles that use gas inefficiently responded as well, but by how much?

We learned in Chapter 3 that consumers respond to higher prices by buying less, while producers respond to higher prices by producing more. We also know that as prices rise, demand for complements falls while demand for substitutes rises. However, we have not yet measured the extent of such responses. In other words, how responsive are consumers and producers to changes in prices in terms of what is purchased and what is produced?

We answer the important “how responsive” question in this chapter by studying how consumers and producers respond to changes in the price of goods and services.

Elasticity—the responsiveness of one variable to changes in another—is the term economists use to measure this change. In our example above, we know that the price of gasoline is one variable and the quantity of gasoline demanded is the other variable. The concept of elasticity lets us measure the relative change in quantity demanded corresponding to various changes in the price of gasoline.

But as our example shows, elasticity can be measured for many different items. If the price of gasoline changes, how will this affect sales of large cars? Small cars? How would demand for train and bus tickets change? And we not need limit our analysis to prices either. For example, income elasticity measures changes in consumer demand in response to changes in income. As incomes rise with a growing economy, will purchases of cars and trucks pick up? By how much? This is information automakers want to know.

Elasticity: How Markets React to Price Changes

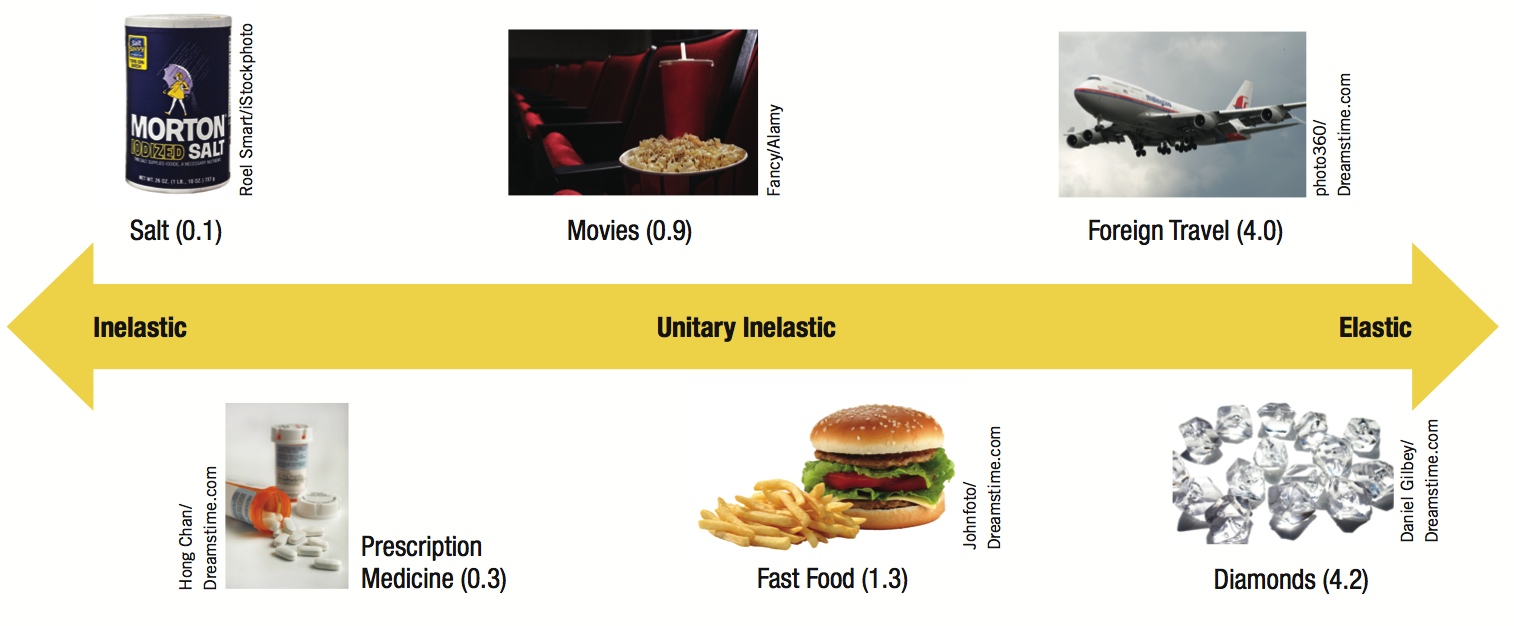

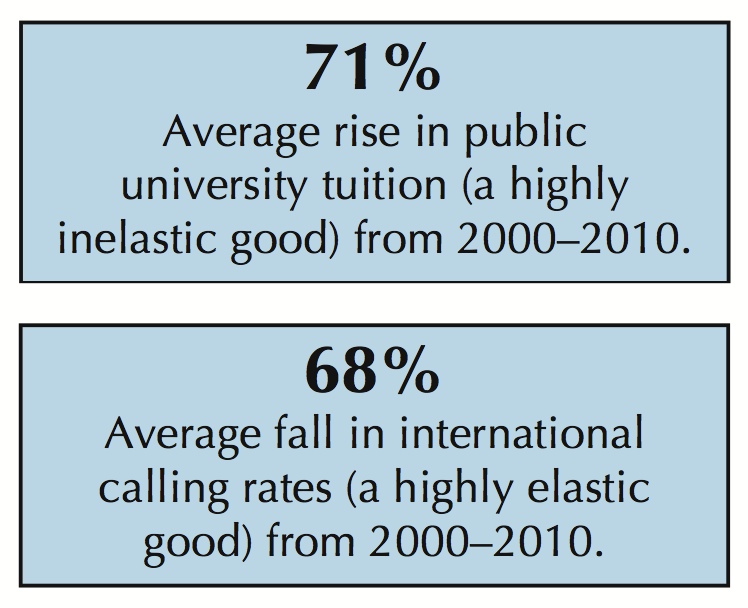

Elasticity varies across goods and services, largely due to factors involving the price of the good, availability of substitutes, and whether a good is a necessity. Elasticity also varies across consumer groups and by country.

Note: The numbers in parentheses refer to the price elasticity of demand.

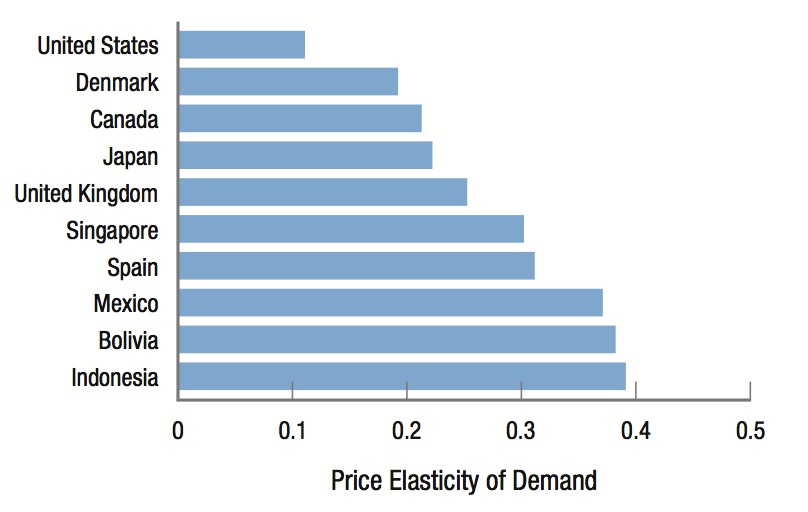

Food is necessary for survival, and thus an inelastic good. Yet, elasticity varies by country; when the price of food rises, poorer countries reduce consumption more than rich countries.

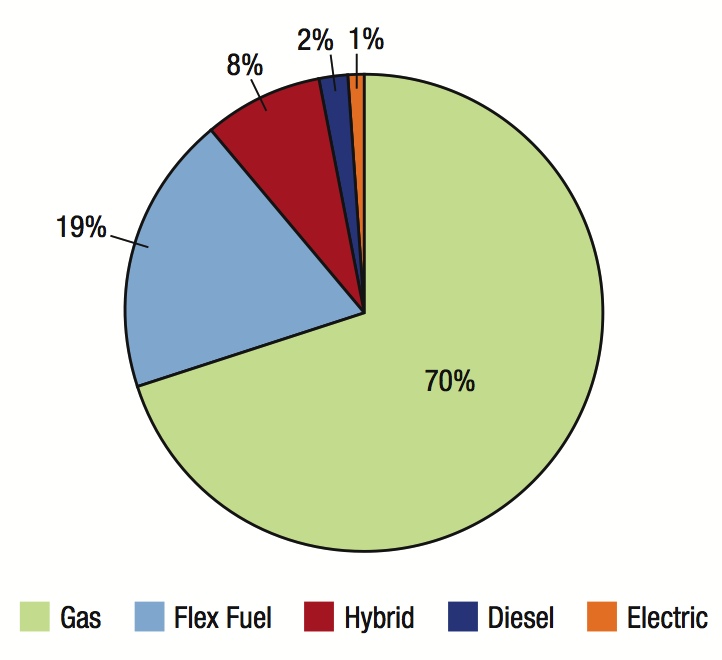

Alternative-fuel cars are growing in popularity. In 2012 they represented 30% of new vehicle sales.

Don’t like paying for parking? You’re not alone. When the price of downtown parking in major cities increased 10%, people on average:

- Used that parking lot 5.4% less.

- Used farther parking lots 8.3% more.

- Used park & ride 3.6% more.

- Rode public transit 2.9% more.

- Reduced the number of trips downtown 4.6%.

Elasticity is a simple economic concept that nonetheless contains a tremendous amount of information about demand for specific products. If a firm raises its price by 50 cents, will it end up with more in revenue, or will the increase in price lead to a drop in quantity demanded that more than offsets the price increase? Knowing a product’s price elasticity allows economists to predict the amount by which quantity demanded will drop in response to a price increase, or grow in response to a price decrease. The concept of elasticity helps you to put supply and demand concepts to work.