Monopoly Markets

monopoly A one-firm industry with no close product substitutes and with substantial barriers to entry.

The very word monopoly almost defines the subject matter: a market in which there is only one seller. For example, if you pay an electric bill every month, it’s likely that you do not have a choice of which electric company services your apartment or house. Economists define a monopoly as a market sharing the following characteristics:

- The market has just one seller—one firm is the industry. This contrasts sharply with the competitive market, where many sellers comprise the industry.

- No close substitutes exist for the monopolist’s product. Consequently, buyers cannot easily substitute other products for that sold by the monopolist. In the case of electricity, you could install solar panels, but such options are often prohibitively expensive.

- A monopolistic industry has significant barriers to entry. Though competitive firms can enter or leave industries in the long run, monopoly markets are considered nearly impossible to enter. Thus monopolists face no competition, even in the long run.

market power A firm’s ability to set prices for goods and services in a market.

This gives pure monopolists what economists call market power. Unlike competitive firms, which are price takers, monopolists are price makers. Their market power allows monopolists to adjust their output in ways that give them significant control over product price.

As we noted already, nearly every firm has some market power, or some control over price. Your neighborhood dry cleaner, for instance, has some control over price because it is located close to you, and you are probably not going to want to drive 5 miles just to save a few cents. This control over price reaches its maximum in the case of monopolies, and becomes minor as markets approach more competitive conditions at the other end of the market structure spectrum.

Sources of Market Power

barriers to entry Any obstacle that makes it more difficult for a firm to enter an industry, and includes control of a key resource, prohibitive fixed costs, and government protection.

Monopoly is defined as one firm serving a market in which there are no close substitutes and entry is nearly impossible. Market power means that a firm has some control over price. As a market structure approaches monopoly, one firm gains the maximum market power possible for that industry. The key to the market power of monopolies is significant barriers to entry. These barriers can be of several forms.

Control Over a Significant Factor of Production If a firm owns or has control over an important input into the production process, that firm can keep potential rivals out of the market. This was the case with Alcoa Aluminum 70 years ago. Alcoa owned nearly all the world’s bauxite ore, a key ingredient in aluminum production, before the company was eventually broken up by the government.

A contemporary example would be the National Football League (NFL), which has negotiated exclusive rights with colleges to draft top players (the most important input), along with exclusive rights with television networks and sponsors to broadcast games. Such control over key components of football entertainment makes entry into the industry very difficult.

economies of scale As the firm expands in size, average total costs decline.

Economies of Scale The economies of scale in an industry (when average total costs decline with increased production) give an existing firm a competitive advantage over potential entrants. By establishing economies of scale early, an existing firm has the ability to underprice new competitors, thereby discouraging their entry into the market. By doing so, a firm increases its market power.

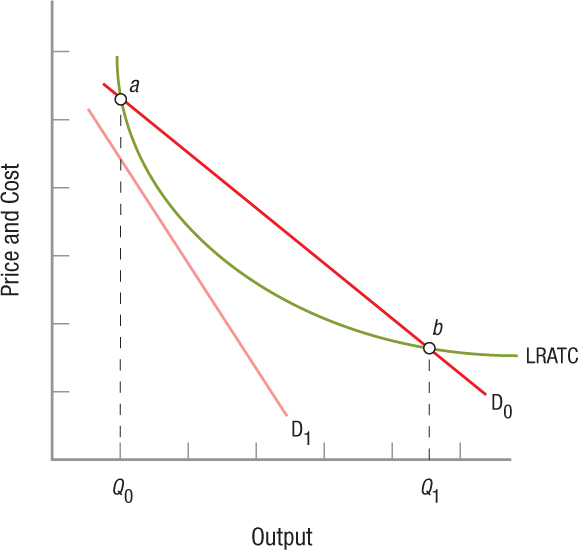

In some industries, economies of scale can be so large that demand supports only one firm. Figure 1 illustrates this case. Here the long-run average total cost curve (LRATC) shows extremely large economies of scale. With industry demand at D0, one firm can earn economic profits by producing between Q0 and Q1. If the industry were to contain two firms, however, demand for each would be D1, and neither firm could remain in business without suffering losses. Economists refer to such cases as natural monopolies.

FIGURE 1

Economies of Scale Leading to Monopoly The economies of scale in an industry can be so large that demand supports only one firm. In the industry portrayed here, one firm could earn economic profits (by producing output between Q0 and Q1 when faced with demand curve D0). If the industry consisted of two firms, however, demand for each would be D1, and neither firm could remain in business without suffering losses.

Utility industries have traditionally been considered natural monopolists because of the high fixed costs associated with power plants and the inefficiency of several different electric companies stringing their wires throughout a city. Recent technology, however, is slowly changing the utilities industry, as smaller plants, solar units, and wind generators permit a smaller yet efficient scale of operations. Smaller plants can be quickly turned on and off, and the energy from the sun and wind is beginning to be stored and transported to where it is needed in the system.

Government Franchises, Patents, and Copyrights The government is the source of some barriers to market entry. A government franchise grants a firm permission to provide specific goods or services, while prohibiting others from doing so, thereby eliminating potential competition. The United States Postal Service, for example, has an exclusive franchise for the delivery of mail to your mailbox. Similarly, water companies typically are granted special franchises by state or local governments.

Patents provide legal protection to individuals who invent new products and processes, allowing the patent holder to reap the benefits from the creation for a limited period, usually 20 years. Patents are immensely important to many industries, including pharmaceuticals, technology, and automobile manufacturing. Many firms in these industries spend huge sums of money each year on research and development—money they might not spend if they could not protect their investments through patenting. Similarly, a copyright protects ideas created by individuals or firms in the form of books, music, art, or software code, allowing these innovators to benefit from their creativity.

Some firms guard trade secrets to protect their assets for even longer periods than the limited timeframes provided by patents and copyrights. Only a handful of the top executives at Coca-Cola, for instance, know the secret to blending Coke.

Monopoly Pricing and Output Decisions

Monopolies gain market power because of their barriers to entry. Shortly we will discuss some ways in which this power is maintained. First, however, let us consider the basics of monopoly pricing and output decisions. In the previous chapter, we saw that competitive firms maximize profits by producing at a level of output where MR = MC, selling this output at the established market price. The monopolist, however, is the market. It has the ability to set the price by adjusting output.

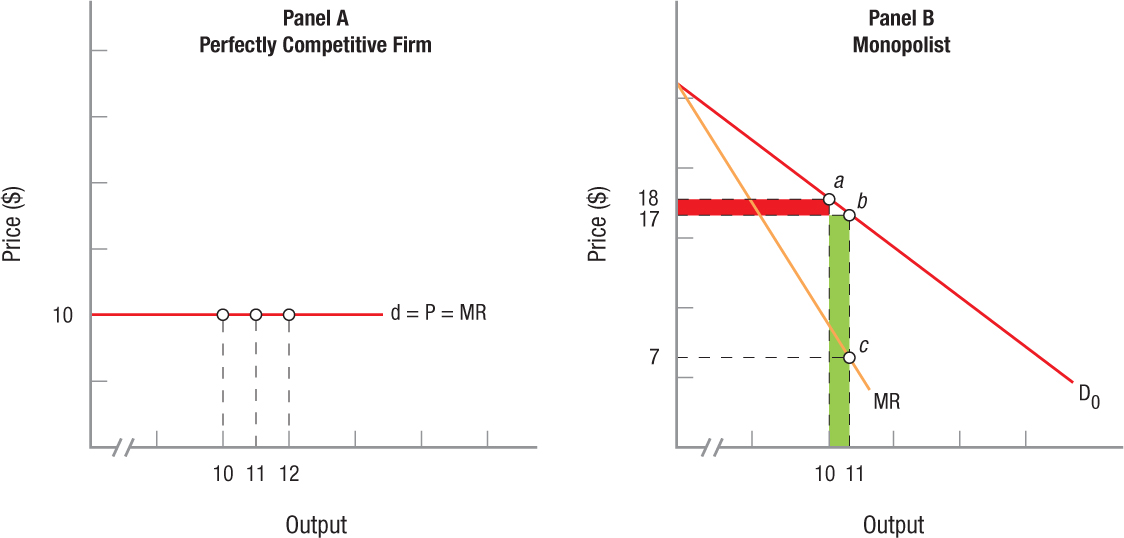

MR < P for Monopoly A monopolist faces a demand curve, just like a perfectly competitive firm. But there is a big difference. For the monopolist, marginal revenue is less than price (MR < P). To see why, look at Figure 2. Panel A shows the demand curve for a perfectly competitive firm. At a price of $10, the competitive firm can sell all it wants. For each unit sold, total revenue rises by $10. Recalling that marginal revenue is equal to the change in total revenue from selling an added unit of the product, marginal revenue is also $10.

FIGURE 2

Marginal Revenue for Monopolies and Perfectly Competitive Firms Panel A shows the demand curve for a perfectly competitive firm. At a price of $10, the competitive firm can sell all it wants. For each unit sold, revenue rises by $10; hence, marginal revenue is $10. Panel B shows the demand curve for a monopolist. Because the monopolist constitutes the entire industry, it faces a downward sloping demand curve (D0). If the monopolist decides to sell 10 units at $18 each (point a), total revenue is $180. Alternatively, if the monopolist wants to sell 11 units, the price must be dropped to $17 (point b). This raises total revenue to $187 (11 × $17), but marginal revenue falls to $7 ($187 − $180, point c). Gaining the added $17 in revenue from the sale of the 11th unit requires the monopolist to give up $10 in additional revenue that would have come from selling the previous 10 units for an extra $1, or $18 each.

Contrast this with the situation of the monopolist in panel B. Because the monopolist constitutes the entire industry, it faces the downward sloping demand curve (D0). If the monopolist decides to produce and sell 10 units, they can be sold in the market for the highest price the market would pay for 10 units (based on the demand curve), which is $18 each (point a), generating total revenue of $180. Alternatively, if the monopolist wants to sell 11 units, the price must be dropped to $17 (point b). This raises total revenue to $187 (11 × $17). Notice, however, that marginal revenue, or the revenue gained from selling this added unit, is only $7 ($187 − $180). In other words, the $17 in revenue (shown in green) gained from the sale of the 11th unit requires that the monopolist give up $10 in revenue (shown in red) that would have come from selling the previous 10 units for $1 more, or $18 each. Marginal revenue for the 11th unit is shown as $7 (point c) in panel B, which is also the difference between the green and red areas.

Notice that we are assuming that the monopolist cannot sell the 10th unit for $18 and then sell the 11th unit for $17; rather, the monopolist must offer to sell a given quantity to the market at a single price per unit. We are assuming, in other words, that there is no way for the monopolist to separate the market by specific individuals who are willing to pay different prices for the product. Later in this chapter, we will relax this assumption and discuss price discrimination.

In summary, we can see from panel B of Figure 2 that MR < P, and the marginal revenue curve is always plotted below the demand curve for the monopolist. This contrasts with the situation of the perfectly competitive firm, for which price and marginal revenue are always the same. We should also note that marginal revenue can be negative. In such an instance, total revenue falls as the monopolist tries to sell more output. However, no profit maximizing monopolist would knowingly produce in this range because costs are rising even as total revenue is declining, thus reducing profits.

Equilibrium Price and Output As noted earlier, product price is determined in a monopoly by how much the monopolist wishes to produce. This contrasts with the perfectly competitive firm that can sell all it wishes, but only at the market-determined price. Both types of firms wish to make profits. Finding the monopolist’s profit maximizing price and output is a little more complicated, however, because competitive firms have only output to consider.

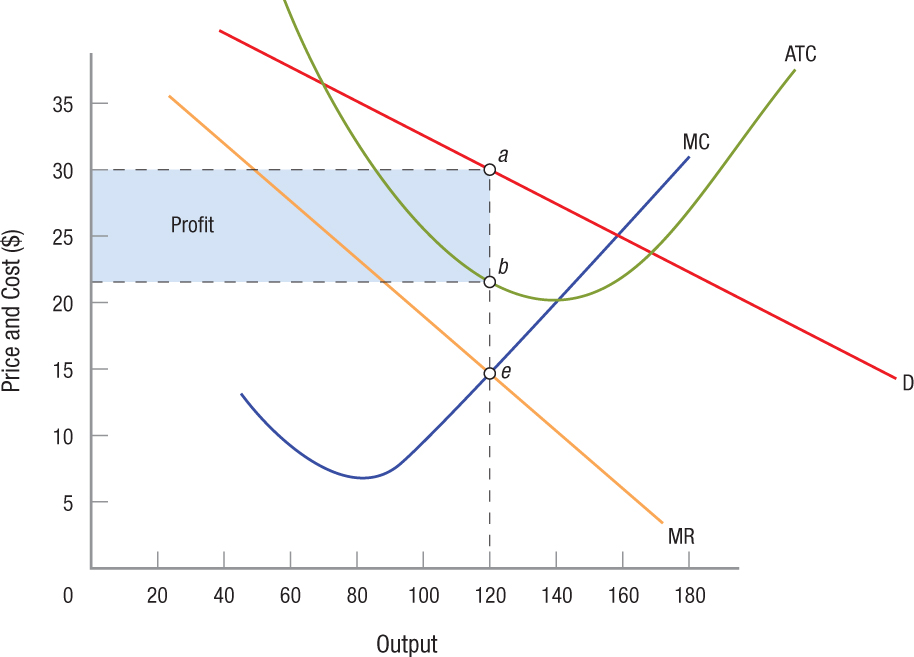

Like competitive firms, the profit maximizing output for the monopolist is found where MR = MC. Turning to Figure 3, we find that marginal revenue equals marginal cost at point e, where output is 120 units. Now we must determine how much the monopolist will charge for this output. This is done by looking to the demand curve. An output of 120 units can be sold for a price of $30 (point a).

FIGURE 3

Monopolist Earning Economic Profits Profit maximizing output is found for monopolists, as for competitive firms, at the point where MR = MC. In this figure, marginal revenue equals marginal cost at point e, where output is 120 units. These 120 units are sold for $30 each (point a). Profit is equal to average profit per unit times units sold: Profit = (P − ATC) × Q = ($30 − $22) × 120 = $8 × 120 = $960. The shaded area represents profit.

Profit for each unit is equal to $8, the difference between price ($30) and average total cost ($22). Profit per unit times output equals total profit ($8 × 120 = $960), as indicated by the shaded area in Figure 3. Following the MR = MC rule, profits are maximized by selling 120 units of the product at $30 each.

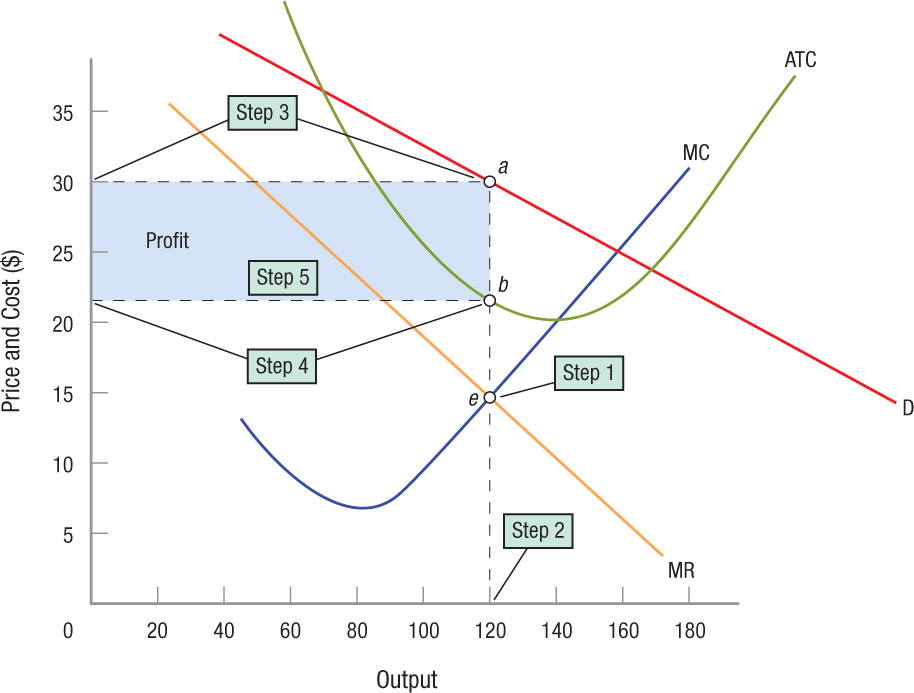

Using the Five Steps to Maximizing Profit We can use the same five-step approach to analyzing equilibrium for a profit maximizing monopolist as we used for a perfectly competitive firm in the previous chapter. The main difference is that for a monopolist, the demand and marginal revenue curves are downward sloping, but that does not change the procedure, as shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4

Five-Step Process to Determine a Monopolist’s Optimal Output, Price, and Profit The same five steps that were used to determine the profit maximizing output, price, and profit in a perfectly competitive market can be used in a monopoly market. The process begins by finding MR = MC, and then locating the optimal output and price, average total cost, and finally profit.

Step 1: Find the point at which MR = MC.

Step 2: At that point, look down and determine the profit maximizing output on the horizontal axis.

Step 3: At this output, extend a vertical line upward to the demand curve and follow it to the left to determine the equilibrium price on the vertical axis.

Step 4: Using the same vertical line, find the point on the ATC curve to determine the average total cost per unit on the vertical axis.

Step 5: Find total profit by taking P − ATC, and multiply by output.

Using the five-step process to determine a monopolist’s optimal output, price, and profit is a useful way to avoid making mistakes when analyzing revenue and cost curves. The same five steps can be used to analyze a perfectly competitive market, as shown in the previous chapter, and a monopolistically competitive market, as will be seen in the next chapter.

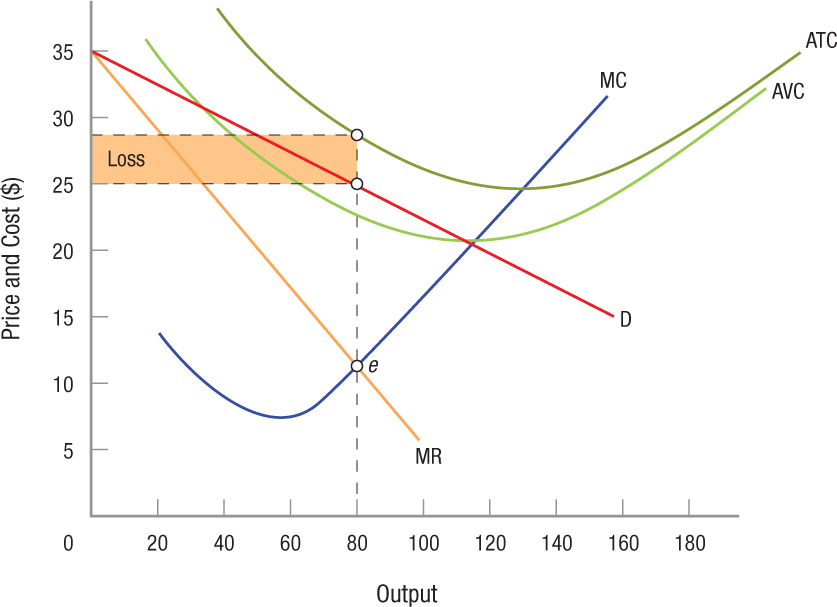

Monopoly Does Not Guarantee Economic Profits We have seen that competitive firms may or may not be profitable in the short run, but in the long run, they must earn at least normal profits to remain in business. Is the same true for monopolists? Yes. Consider the monopolist in Figure 5. This firm maximizes profits by producing where MR = MC (point e) and selling 80 units of output for a price of $25.

FIGURE 5

Monopolist Firm Making Economic Losses Like perfectly competitive firms, monopolists may or may not be profitable in the short run, but in the long run, they must at least earn normal profits to remain in business. The monopolist shown here maximizes profits (minimizes losses) by producing at point e, selling 80 units of output at $25 each. Price is lower than average total cost, so the monopolist suffers the loss indicated by the shaded area. Because price still exceeds average variable cost (AVC), in the short run the monopolist will minimize its losses by continuing to produce.

In this case, however, price ($25) is lower than average total cost ($28), and thus the monopolist suffers the loss of $240 (−$3 × 80 = −$240) indicated by the shaded area. Because price nonetheless exceeds average variable costs, the monopolist will minimize its losses in the short run by continuing to produce. But if price should fall below AVC, the monopolist, just like any competitive firm, will minimize its losses at its fixed costs by shutting down its plant. If these losses persist, the monopolist will exit the industry in the long run.

This is an important point to remember. Being a monopolist does not automatically mean that there will be monopoly profits to haul in. Even monopolies face some cost and price pressures, and they face a demand curve, which ultimately limits their price making.

“But Wait…There’s More!” The Success and Failure of Infomercials

“But wait…there’s more!” is a familiar phrase to anyone who has watched an infomercial selling unique products that generally are not sold in retail stores. The size of the infomercial industry is significant and growing. In 2012, infomercials generated over $150 billion in sales. What do infomercials sell? Why are they successful and why do many infomercial products fail?

Unlike regular television commercials, which air for 30 seconds or one minute during daytime and primetime shows, infomercials typically are longer, ranging from one minute to 30 minutes or longer. The longest infomercials typically air in the middle of the night when television advertising rates are much lower.

Infomercials typically sell newly invented products that are not well known. Most infomercial products fit the monopoly market structure because although the product may have similarities to other products, infomercials advertise them as one-of-a-kind products. Examples include new types of knives, towels, beauty products, and workout equipment. However, because not all infomercials are able to convince prospective buyers of the distinction from existing products, many infomercial products fail.

Infomercials focus on the product characteristics that make the product completely different from anything on the market. Because the target market of infomercials is consumers who buy on impulse, even in the middle of the night, they use various techniques to increase sales. First, many infomercials show a high “retail” price (such as $100) and then reduce it rapidly until it becomes $19.99. Second, infomercials will offer something extra with the tag line “But wait…there’s more!” Third, many infomercials show a fixed time period in which to buy, often within hours, even if the deadline is not actually enforced. And last, infomercials tend to offer return policies and often lifetime warranties (which is attractive but not that valuable if the company fails).

Some infomercials have become remarkably successful, with the product even becoming sold in stores. One example of a successful product that started from an infomercial is the Ped Egg, a cheese-grater-like device that removes dead skin from one’s feet, which has sold over 50 million units and is now available through retailers such as Walgreens and Amazon.com.

MONOPOLY MARKETS

- Monopoly is a market with no close substitutes, high barriers to entry, and one seller; the firm is the industry. Hence, monopolists are price makers.

- Monopolies gain maximum market power from control over an important input, economies of scale, or from government franchises, patents, and copyrights.

- For the monopolist, MR < P because the industry’s demand is the monopolist’s demand.

- Profit is maximized by producing that output where MR = MC and setting the price off the demand curve.

- Being a monopolist does not guarantee economic profits if demand is insufficient to cover costs.

QUESTION: When legendary country singer Dolly Parton goes on tour, sometimes she will perform in a relatively small (< 1,500 seats) venue when she could easily fill much larger arenas. Why would music artists intentionally choose a smaller venue? Wouldn’t they make more money if they performed in a larger arena?

By performing in a smaller venue (such as a performing arts hall with 1,500 seats instead of an arena with 10,000 or more seats), the artist can target the core fans willing to pay high prices for tickets. With market power in pricing (there is only one Dolly Parton), nearly all seats would be sold at the high price, as opposed to having to offer much lower prices to fill a larger arena. If the costs of performing at a larger arena are significant, artists can do better by producing less (selling fewer tickets), charging a much higher price, and reducing the costs of putting on the concert.