Comparing Monopoly and Competition

We have seen that perfectly competitive firms are price takers and produce as much as they can where MR = MC. In contrast, monopolies are price makers: They have the market power to set price and quantity, constrained only by their demand curve.

Would our economy be better off with more or fewer monopolies? This question almost answers itself. Who would want more monopolies—except the few lucky monopolists? The answer is, consumers are better off when competition is strong and monopolies are limited to certain industries. The reasons for this have to do with the losses associated with monopoly markets and market power. Losses directly attributed to monopolies include reduced output at higher prices, deadweight losses, rent-seeking behavior of monopolists, and x-inefficiency losses. But as we’ll see later in this section, part (but not all) of these losses can be at least partially offset by some benefits that monopolies provide.

Higher Prices and Lower Output from Monopoly

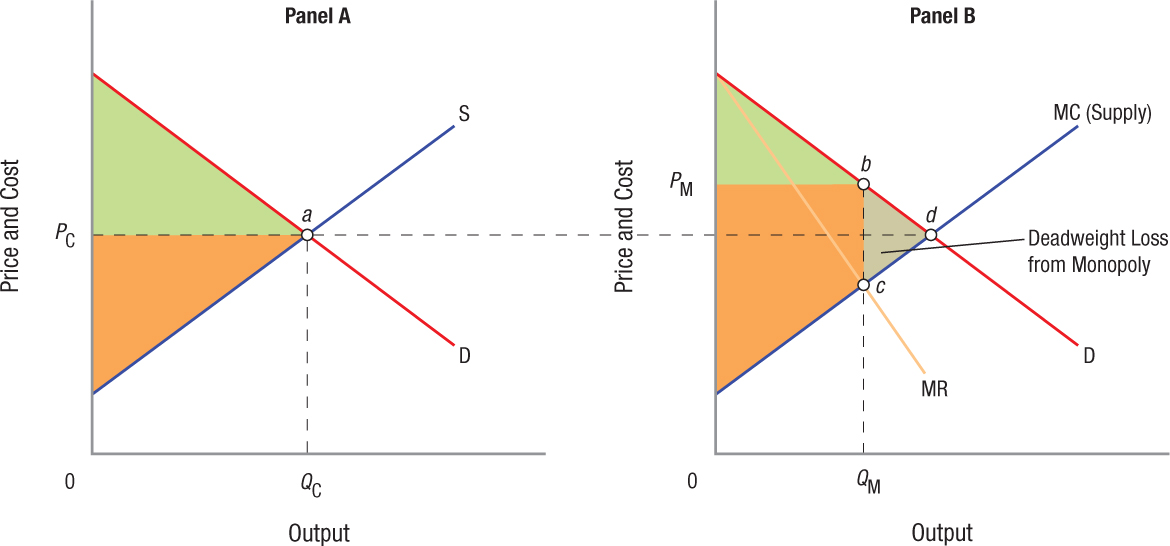

Imagine for a moment that a competitive industry is monopolized, and the monopolist’s marginal cost curve happens to be the same as the competitive industry’s supply curve. Figure 6 illustrates such a scenario. In panel A, the competitive industry produces where supply equals demand, and thus where price and output are PC and QC (point a). In panel B, monopoly price and output, as previously determined, are PM and QM (point b).

FIGURE 6

Monopoly Inefficiency This figure shows what would happen if a competitive industry were monopolized and the new monopolist’s marginal cost curve was the same as the competitive industry’s supply curve. When the industry was competitive, it produced where S = D, and thus where price and output are PC and QC (point a in panel A). Monopoly price and output, however, are PM and QM (point b in panel B); output is lower and price is higher than the corresponding values for competitive firms. As a result, part of consumer surplus (shown in green) is transferred into producer surplus (shown in orange) in a monopoly, and in the process, inefficiency is created in the form of deadweight loss (shaded area bcd).

Clearly, monopoly output is lower, and monopoly price is higher, than the corresponding values for competitive industries. How does this translate into the welfare of consumers and producers? Recall that we measure consumer surplus as the difference between market demand and price, as shown by the green areas in each panel. Producer surplus is the difference between price and market supply (marginal cost) as shown by the orange areas in each panel. The higher price charged by a monopolist results in part of the consumer surplus from Panel A being transferred into producer surplus in Panel B. Panel B shows a smaller consumer surplus and a larger producer surplus under a monopoly compared to a competitive market in Panel A. But this is not the end of the story.

Notice that at monopoly output QM, consumers value the QMth unit of the product at PM (point b), even though the cost to produce this last unit of output is considerably less (point c). This difference creates inefficiency because additional beneficial transactions could take place if output were expanded. The deadweight loss, otherwise known as the welfare loss, is comprised of consumer surplus and producer surplus that is lost from producing less than the efficient output. In panel B, deadweight loss from monopoly is shown as the shaded area bcd. This area represents the deadweight loss to society from a monopoly market.

Even though deadweight loss derives partly from lost producer surplus, monopoly firms willingly forgo this portion of producer surplus in order to transfer a larger portion of consumer surplus into producer surplus (the orange rectangular area above the Pc line in Panel B). Therefore, monopoly firms use their market power to gain producer surplus at the expense of consumers and create inefficiency in the form of deadweight loss. But this is not the only source of inefficiency caused by firms with complete market power.

Rent Seeking and X-Inefficiency

Monopolies earn economic profits by producing less and charging more than competitive firms. Although these actions generate deadweight loss, monopolists are protective of the profits they earn. If barriers to entry to the market were eased, economic profit would evaporate as price falls, as it does in competitive markets. How, then, can a monopolist protect itself from potential competition? One way is to spend resources that could have been used to expand its production on efforts to protect its monopoly position.

rent seeking Resources expended to protect a monopoly position. These are used for such activities as lobbying, extending patents, and restricting the number of licenses permitted.

Economists call this behavior rent seeking—behavior directed toward avoiding competition. Firms hire lawyers and other professionals to lobby governments, extend patents, and engage in a host of other activities intended solely to protect their monopoly position. For example, in order to pick up passengers on the street, taxis in New York City require a medallion registered with the Taxi and Limousine Commission; restricting the number of medallions drives up their price and gives medallion holders a further incentive to restrict the number of new medallions issued, by lobbying and other means. Many industries spend significant resources lobbying Congress for tariff protection to reduce foreign competition. All these activities are inefficient, in that they use resources and shift income from one group to another without producing a useful good or service. Rent seeking thus represents an added loss to society from monopoly.

x-inefficiency Protected from competitive pressures, monopolies do not have to act efficiently. Spending on corporate jets, travel, and other perks of business represents x-inefficiency.

Another area in which society might lose from monopolies is called x-inefficiency. Some economists suggest that because monopolies are protected from competitive pressures, they do not have to operate efficiently. Management can offer itself and their employees perks, such as elaborate corporate retreats or suites at professional sports stadiums, without worrying about whether costs are kept at efficient levels. Deregulation over the last several decades, particularly in the communications and trucking industries, has provided ample evidence of inefficiencies arising when firms are protected from competition by government regulations. Many firms in these industries had to cut back on lavish expenses when competitive pressures were reintroduced into their industries.

Monopolies and Innovation

Much of our analysis of monopolies has focused on the inefficiencies created and the detrimental effects on consumers. However, monopolies do create some benefits that are shared among all of society. For example, monopolies provide new products, technologies, and medical breakthroughs that benefit many consumers. The incentives to earn monopoly profits created by patents and copyrights encourage firms to invest in developing these new products. Otherwise, what firm would be willing to spend hundreds of millions of dollars inventing a product only to have it copied and sold by other firms?

Similarly, much of the entertainment industry, including music, television shows, books, and movies would not exist to such a great extent if copyrights did not provide singers, authors, and other media creators the monetary incentive to create such products for our enjoyment. Therefore, the ability to achieve market power through innovation provides an incentive to individuals and firms to invest time and money to create new products and other creative works that could generate substantial profits over time.

Benefits Versus Costs of Monopolies

Are there any other benefits to monopolies aside from innovation? The answer to this question is, “Possibly yes, though generally no.” If the economies of scale associated with an industry are so large that many small competitors would face substantially higher marginal costs than a monopolist, a monopolist would produce and sell more output at a lower price than could competitive firms. This is the case of natural monopolies, and the justification for why monopolies are allowed to exist in industries such as the provision of water or electricity in many communities.

Imagine what might happen if a storm knocks out power to your neighborhood, and instead of one electric company restoring power to your street, each household needed to wait for its specific electricity provider to show up.

Larger firms, moreover, can allocate more resources to research and development than smaller firms, and the possibility of economic profits may be the incentive monopolists require to invest.

Still, economists tend to doubt that monopolies are beneficial enough to outweigh their disadvantages.

In actuality, pure monopolies are rare, in part because of public policy and antitrust laws—more about this later in this chapter—and in part because rapidly changing technologies limit most monopolies to short-run economic profits—witness the battle between Facebook and Google+ for domination of social media services, and Sony, Amazon.com, Apple, and several other firms to dominate the eBook market. Even so, firms seek to increase their market power by trying to become monopolies and gain the ability to influence price.

We have seen what monopolies are and how they arise. We also saw why a monopolist produces less than the socially optimal quantity at a higher than socially necessary price, and witnessed how monopoly compares unfavorably to the competitive model. Furthermore, we looked at an expensive drawback of monopolies: the amount of resources wasted in maintaining a monopolist’s position. In the next section, we relax the assumption of one price, revealing what monopolies are always trying to do.

COMPARING MONOPOLY AND COMPETITION

- Monopoly output is lower and price is higher when compared to competition, resulting in a deadweight loss.

- Monopolies are subject to rent-seeking behavior directed toward avoiding competition (lobbying and other activities to extend the monopoly).

- Because monopolies are protected from competitive pressures, they often engage in x-inefficiency behavior—extending perks to management and other inefficient activities.

- Monopolies can provide benefits in the form of economies of scale and incentives to innovate. However, these benefits are outweighed by the costs resulting from the lack of competition.

QUESTION: Google has over 70% of the search business on the Internet and generates a great deal of advertising revenue. Microsoft has 85% of the operating system business, 55% of the Internet browsers in use, and a growing search engine market. In late 2012, Microsoft accused Google of engaging in dishonest searches in the online shopping market (which Google denied) by listing search results based on how much merchants are willing to pay in ads. Microsoft even launched a Web site and campaign called “Scroogled” whose main purpose was to attack Google. Do these actions by Microsoft feel a little like monopolistic rent-seeking? Should the government step in, or is this just competition between giants?

Although Microsoft’s actions in this case do not involve lobbying for special privileges (the traditional definition of rent seeking), its tactics nonetheless resemble rent seeking in that costly (even wasteful) actions are being used to protect one’s market share. Microsoft has a huge capital base and cash flow, and could compete with Google in the search market without the need to make accusations regarding its business practices.