Price Discrimination

price discrimination Charging different consumer groups different prices for the same product.

perfect (first-degree) price discrimination Charging each customer the maximum price each is willing to pay, thereby expropriating all consumer surplus.

second-degree price discrimination Charging different customers different prices based on the quantities of the product they purchase.

third-degree price discrimination Charging different groups of people different prices based on varying elasticities of demand.

When firms have some market power, they will try to charge different customers different prices for the same product. For example, senior citizens might pay less for a movie ticket than you do. This is called price discrimination and it is used to increase the firm’s profits by converting part or all of consumer surplus into producer surplus. If a product costs $100 in a competitive market but you are willing to pay $150, a monopolist wants to grab as much of your $50 consumer surplus as possible.

Remember that unlike monopolies, competitive firms cannot price discriminate because they get their prices from the market (they are price takers). Several conditions are required for successful price discrimination:

- Sellers must have some market power.

- Sellers must be able to separate the market into different consumer groups based on their elasticities of demand.

- Sellers must be able to prevent arbitrage; that is, it must be able to keep low-price buyers from reselling to higher-price buyers.

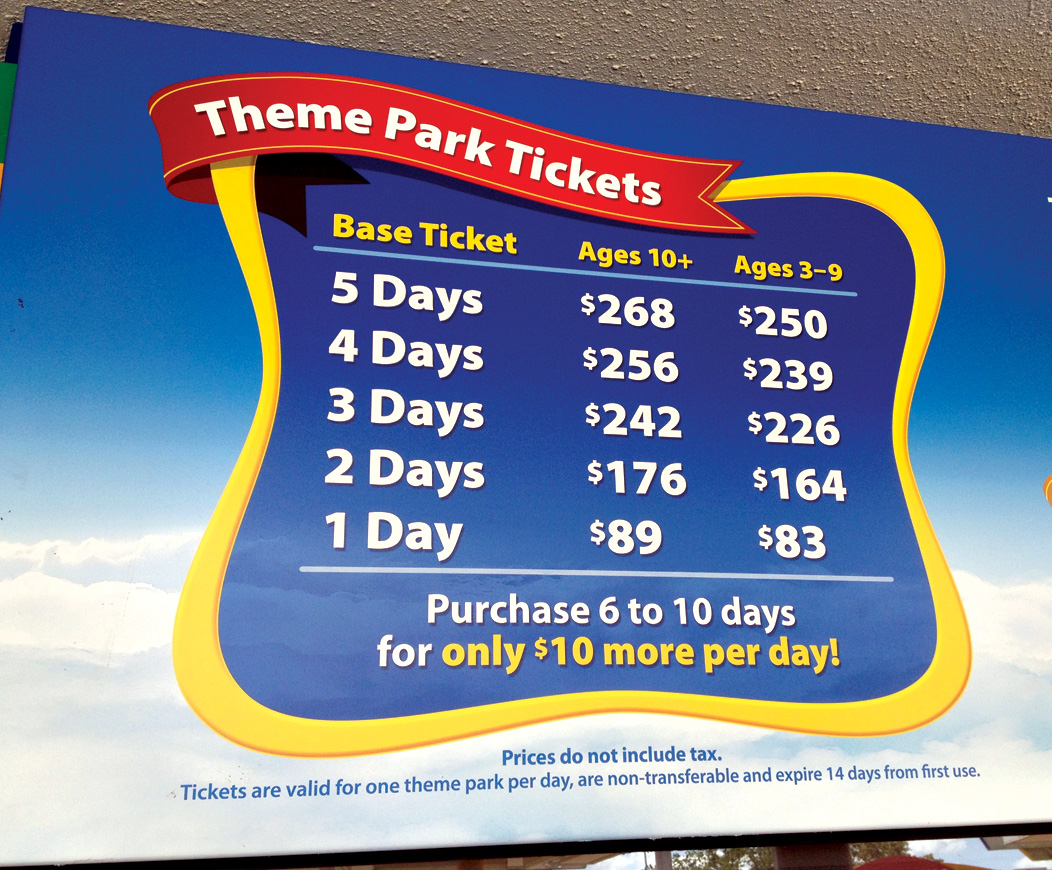

There are three major types of price discrimination. The first is known as perfect (first-degree) price discrimination. It involves charging each customer the maximum price each is willing to pay. Because firms cannot always determine individual willingness-to-pay, other forms of price discrimination exist. Second-degree price discrimination involves charging different customers different prices based on the quantities of the product they purchase. The final and most common form of price discrimination is third-degree price discrimination,> which occurs when firms charge different groups of people different prices. This is an everyday occurrence with airline, bus, and movie theater tickets.

Perfect (First-Degree) Price Discrimination

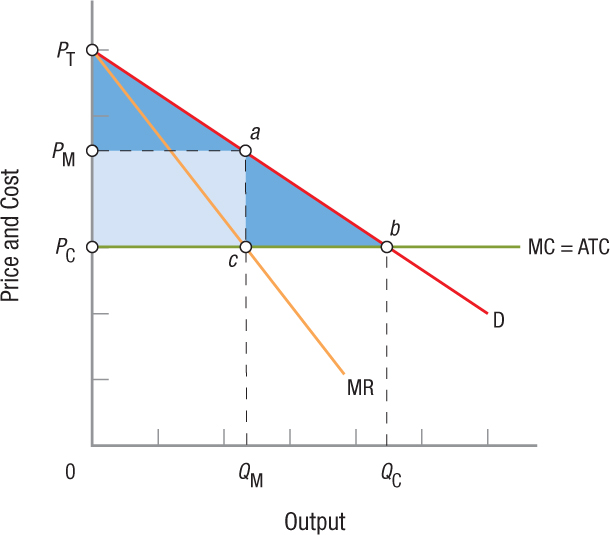

When perfect price discrimination can be employed, a firm will charge each customer the maximum price each is willing to pay. This type of price discrimination is perhaps best exemplified by an online auction, where buyers often bid up the price of a good to their maximum willingness to pay. Figure 7 portrays such a scenario for a market with constant cost conditions (assumed for simplicity) and where one unit of the good is offered to the highest bidder each day. Every point on the demand curve represents a price. The first few customers—those who value the product the most—are charged a high price. The next customers are charged slightly lower prices, the QMth customer is charged PM (point a), and so on, until the last unit is sold to the QCth customer for PC (point b). As a result, a perfectly discriminating monopolist earns profits equal to the shaded area PCPTb.

FIGURE 7

Perfect Price Discrimination With perfect price discrimination, firms charge each customer the maximum price each is willing to pay in order to extract all consumer surplus. Thus, every point on the demand curve in this figure represents a price. The first few customers—those who value the product most—are charged a high price. The next customers are charged a slightly lower price, and so on, until the last unit is sold for PC (point b). As a result, a perfectly discriminating monopolist earns profits represented by the shaded area PCPTb. This is considerably more profit than the monopolist would earn by selling QM units at price PM, represented by area PCPMac.

Figure 7 shows why firms would want to price discriminate. Typical monopoly profits in this case, assuming the monopolist sells QM units at price PM, would be the rectangle area PCPMac (the lighter shaded area). This area is considerably smaller than the triangle PCPTb, earned by the perfectly price discriminating monopolist. That is why price discrimination exists—it is profitable. Note also that the last unit of the product sold by this monopolist is priced at PC, the competitive price. In this limited sense, then, the monopolist who can perfectly price discriminate is as efficient as a competitive firm. Notice that perfectly price discriminating monopolists manage to expropriate the entire consumer surplus.

Second-Degree Price Discrimination

Second-degree price discrimination involves charging consumers different prices for different blocks of consumption. For example, by purchasing items in bulk (such as a pack of six tubes of toothpaste) at Costco or Sam’s Club, the cost per unit is typically less than buying just one tube at the local store. Similarly, producers of electric, gas, and water utilities often incorporate block pricing. You pay one rate for the first so many kilowatt-hours of electricity and a lower rate for more, and so on.

The rationale for second-degree price discrimination is twofold. First, the cost of selling many units of a good to one customer is often less than that of selling a single unit to many customers due to overhead costs such as cashiers and accounting expenses. Second, if stores convince consumers to buy more than they had intended by offering discounts, profits can be earned as long as the discounted price exceeds marginal cost.

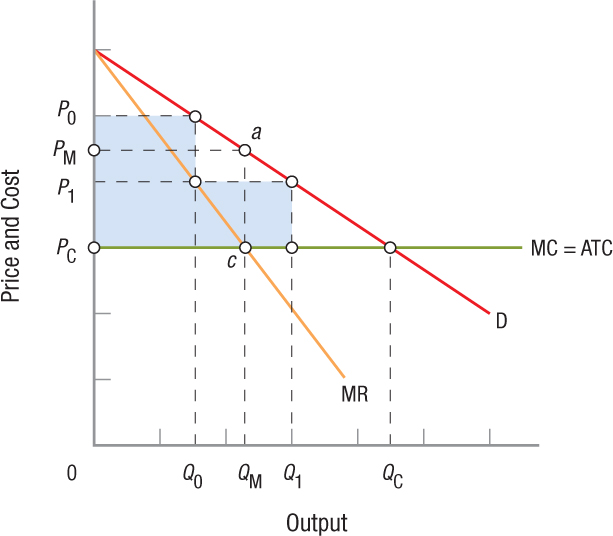

An illustration of second-degree price discrimination is shown in Figure 8 using the block pricing scheme example.

FIGURE 8

Second-Degree Price Discrimination Second-degree price discrimination involves charging different customers different prices based on the quantities of the product they purchase. A single-price monopolist would earn economic profits equal to PCPMac, but by charging three different prices—P0, P1, and PC—profits increase, as shown by comparing the shaded area with area PCPMac.

For the first Q0 units of the product, consumers are charged P0; between Q0 and Q1, the price falls to P1; and after that, the price is reduced to PC. This results in profit to the firm equal to the shaded area. The shaded profit area for the price discriminating monopolist is greater than that of the monopolist charging just one price PM (area PCPMac). The most common price discrimination scheme, however, is third-degree, in which groups of consumers are charged different prices.

Third-Degree Price Discrimination

Third-degree, or imperfect, price discrimination involves charging different groups of people different prices. An obvious example would be the various fares charged for airline flights. Business travelers have much lower elasticities of demand for flights than do vacationers, therefore airlines place all sorts of restrictions on their tickets to separate people into distinct categories. Purchasing a ticket several weeks in advance, for instance—which vacationers can usually do, but businesspeople may not be able to—often results in a significantly lower fare. Arbitrage (the ability of low-price buyers to sell to higher-price buyers) is prevented, meanwhile, by rules stipulating that passengers can only travel on tickets purchased in their name. Other examples of third-degree price discrimination include different ticket prices for children, adults, and seniors at movie theaters; student discounts for many services; and even ladies’ night at clubs.

Firms engage in third-degree price discrimination in order to increase their producer surplus from serving more customers. For example, if a soft ware firm is restricted to offering their product at one price, it would choose the profit maximizing monopoly price, which means customers with lower willingness-to-pay would be priced out of a purchase. However, by offering a discounted price to these customers (and only these customers who otherwise would not have made a purchase), firms can gain more producer surplus as long as the discounted price exceeds the marginal cost of providing the extra units.

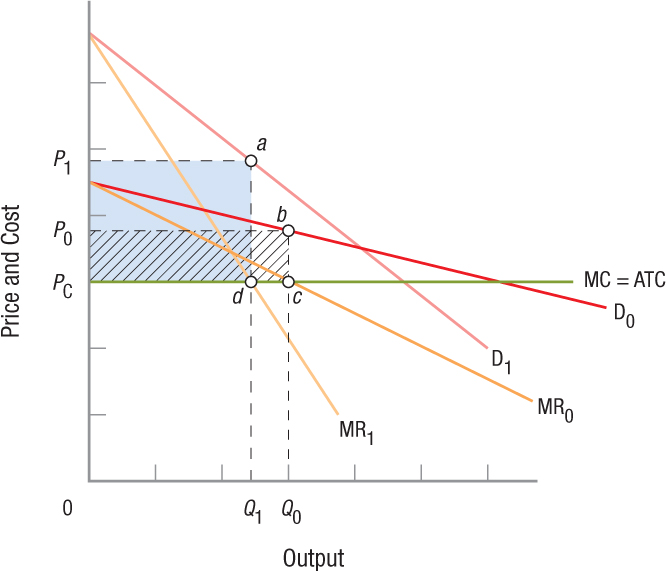

Third-degree price discrimination is illustrated in Figure 9. The two demand curves, D0 and D1, represent two segments of a market with different demand elasticities. The less elastic market, D1, is offered price P1. This is higher than price P0 offered to the more elastic market, D0. Profits are maximized for both markets. For market D0, profits are PCP0bc, and for less elastic market D1, they are PCP1ad. Like the perfectly discriminating monopolist, the third-degree price-discriminating monopolist earns profits that exceed those that would come from a normal one-price policy.

FIGURE 9

Third-Degree Price Discrimination This figure illustrates third-degree price discrimination, in which firms segment markets based on consumers’ willingness-to-pay in order to maximize producer surplus. The two demand curves, D0 and D1, represent two segments of a market with different demand elasticities. The less elastic market, D1, is offered price P1, which is higher than price P0, offered to the more elastic market, D0, thus maximizing the profits in both markets.

We can look at price discrimination in an intuitive way by focusing on a restaurant. Most dinner customers frequent the restaurant after 6:30 p.m. However, the restaurant is still open from 4:30 to 6:30 p.m. and incurs costs (if workers start their shifts before the 6:30 rush). It is in the restaurant’s interest to offer early bird specials, discounting dinners purchased before 6:30, as long as this policy attracts new customers and does not pull in too many of its later-appearing regular diners. In this way, the restaurant generates profits from two separate groups, while charging two separate prices. As long as the restaurant has some market power—it can offer these two prices without driving its regular customers from higher-priced meals to lower-priced meals—it makes sense for it to act this way. Therefore, we can conclude that firms with market power will always try to price discriminate.

Is Flexible Ticket Pricing the New Form of Price Discrimination?

Ticketmaster has long held market power in the entertainment and sports ticket-selling industry. Although Ticketmaster faces competition from other ticket sellers, its market power stems from the exclusivity contracts it establishes with concert promoters, artists, and sports teams.

When an agreement is made with Ticketmaster, it becomes the only site through which consumers can purchase tickets other than the ticket resale market. This gives ticket sellers and the entertainers and shows they represent considerable market power to set prices.

In early 2010, concert promoter Live Nation merged with Ticketmaster, giving the new combined company (Live Nation) even more market power. This allowed the new company to implement new strategies to correct problems with their original pricing model. Specifically, Ticketmaster typically offered several ticket tiers with different prices based on seating location. These prices, however, often are printed on the tickets and do not change.

However, setting prices too low results in a quick sellout, leading to a resale market in which tickets initially sold at one price are resold at much higher prices, with the profits going to the reseller instead of Ticketmaster. Setting prices too high, on the other hand, leaves many tickets unsold and results in many tickets being given away in radio promotions and other deals.

In 2011, Live Nation announced a new flexible pricing model (to be implemented in phases) that has been successfully used in the airline industry. With flexible pricing, concert tickets do not have a fixed price. Instead, ticket prices are set and changed based on demand—if tickets sell too fast, prices would rise; if tickets sell too slowly, prices would fall. This form of price discrimination allows ticket sellers to reap more consumer surplus that otherwise might go to the resale market. This new approach to ticket sales is another example of how firms use strategies to maximize their market power.

In all three types of price discrimination, monopoly firms use their market power to increase their producer surplus. Although part of this increase in producer surplus comes from consumers in the form of higher prices, the rest comes from the reduction in deadweight loss. Unlike a single-price monopolist, efficiency is improved in multiple-price scenarios because more output is being produced, allowing more consumers to purchase the good. Still, all forms of monopoly pricing (single-price or multiple-price through price discrimination) create concerns about the welfare of consumers. Therefore, regulations and rules are sometimes used to reduce the market power firms exert. We turn to these topics in the next section.

PRICE DISCRIMINATION

- Firms with market power price discriminate to increase profits.

- To price discriminate, firms must have some market power (control over price) and must be able to separate the market into different consumer groups based on their elasticity of demand, and firms (sellers) must be able to prevent arbitrage.

- With perfect price discrimination the firm can charge each customer a different price and expropriate the entire consumer surplus for itself.

- Second-degree price discrimination involves charging customers different prices for different quantities of the product.

- Third-degree price discrimination (the most common) involves charging different groups of people different prices.

- Price discrimination may lead to higher prices for some consumers, but it also improves efficiency by allowing more consumers to purchase the good, reducing deadweight loss.

QUESTION: Researchers at Yale University and the University of California, Berkeley, found that minorities and women pay about $500 more on average for a car than white men when bargaining directly with car dealers. However, when minorities and women used online auto retailers such as Autobytel.com to purchase a car, the price discrimination disappeared. Is this price discrimination the same as that discussed in this section? Why or why not?

No, this is not the same type of price discrimination discussed in this section. This type of discrimination occurs because of information problems, gender discrimination, racism, or other factors. The authors conclude that a large part of the price differences between buying online and bargaining in the showroom comes from the fact that online consumers have better information. Price discrimination in this section of the chapter is based on consumers with different elasticities of demand, not information problems or racism. Examples include student, senior, and adult pricing in movie theaters.