Chapter Introduction

After studying this chapter you should be able to:

- Describe the tools that governments use to influence aggregate demand.

- Explain the difference between mandatory and discretionary government spending.

- Determine the influence that the multiplier effect has on government spending on the equilibrium output of an economy.

- Describe expansionary and contractionary fiscal policy.

- Describe the fiscal policies that governments use to influence aggregate supply.

- Describe the impact of automatic stabilizers, lag effects, and the propensity toward deficits from fiscal policymaking.

- Define deficits and the national debt.

- Describe the problems with passing a balanced budget amendment.

- Describe the potential consequences of maintaining high public debt.

When you apply for a loan to buy a car, you undoubtedly will go through a credit check and get a credit rating, which is a number that estimates the probability of you paying back the loan. The government also gets a credit rating for the loans it takes out. This rating, like yours, estimates the probability of the government paying back its loans.

On August 5, 2011, Standard and Poor’s (S&P), a credit rating agency, did something it had never done in its history: lower the debt rating of the United States government from a perfect AAA rating to a slightly less than perfect AA+ rating. Although an AA+ rating is still excellent, this change was significant, because it suggested for the first time that the United States government is not immune from all and any hardships in paying its debts.

Why did the United States government lose its perfect debt rating? One reason was its extensive use of fiscal policy over the last several years. Fiscal policy is the use of government revenue collection (mainly taxation) and spending to influence the economy. In terms of taxation, when the government taxes something, individuals and businesses have less money to spend. Therefore, taxes put the brakes on various economic activities. However, in terms of spending, think of what it means to local employment if the government decides to improve the roads and bridges in a city. By their very nature, taxation and spending affect the economy.

In extraordinary times, governments use fiscal policy to influence the macroeconomy with the express purpose of smoothing fluctuations in the business cycle. During the last recession, in 2007–2009, the Obama Administration added almost $800 billion in additional government spending in an attempt to pull the economy out of its doldrums. If people would not spend, government would spend in their place: Spending was used to spur the economy when citizens were too scared to spend themselves. In inflationary times, government uses fiscal policy to pull money out of people’s hands in an attempt to cool down spending and inflation.

Fiscal policy influences aggregate demand and aggregate supply, the model studied in the previous chapter, in many ways. However, fiscal policy that is used to stimulate the economy is often accompanied by persistent budget deficits and debt. Why and to what end? This chapter will examine these issues and focus on the problem of financing deficits by accruing debt.

Most Americans are accustomed to dealing with debt. Individuals might have a home mortgage, car loan, student loan, or credit card balances, while businesses often take out loans for capital purchases and other expenses to run their operations. Most debt is managed by making periodic payments toward the balance and interest. However, when debt becomes too high to be controlled, individuals and companies face financial distress and are sometimes forced to declare bankruptcy. In 2012, over 1.3 million individuals and over 42,000 businesses filed for bankruptcy.

As we will see, it is no surprise that governments also deal with debt. In recent years, deficits and the national debt have dominated economic headlines. The national debt grows when the government consistently spends more than the tax revenues it collects each year. In 2012, the U.S. government collected about $2.5 trillion in taxes, but spent more than $3.5 trillion. The difference of over $1 trillion represented the federal deficit that was added to the national debt.

Unlike debt for individuals and small companies, a government has a much larger arsenal of tools to prevent it from going bankrupt, including the power to tax and the ever-powerful ability to “print” money. But even those tools can sometimes be rendered useless, causing a government to rack up sizeable debt and increasing the burden of managing the debt. Further, when a government does default on its debt, it can create havoc in markets throughout the world.

In this chapter, we analyze the tools government uses to implement fiscal policy and study their effects on aggregate demand and aggregate supply, which affects income and output. We analyze the bias toward accruing public debt rather than raising taxes or reducing spending. Is the amount of the federal debt a problem, both now and in the future? If so, what can the government do about it? By the time you have finished studying this chapter, you should have a good sense of the scope of fiscal policy and the consequences on the economy of relying on public debt rather than balancing taxes and spending.

Your Government and Its Financial Operation

The U.S. government is one of the largest institutions in the world, taking in revenues of nearly $2.5 trillion each year. Still, the government in recent years has spent much more, accruing deficits of over $1 trillion every year from 2009 to 2012 and adding to its public debt.

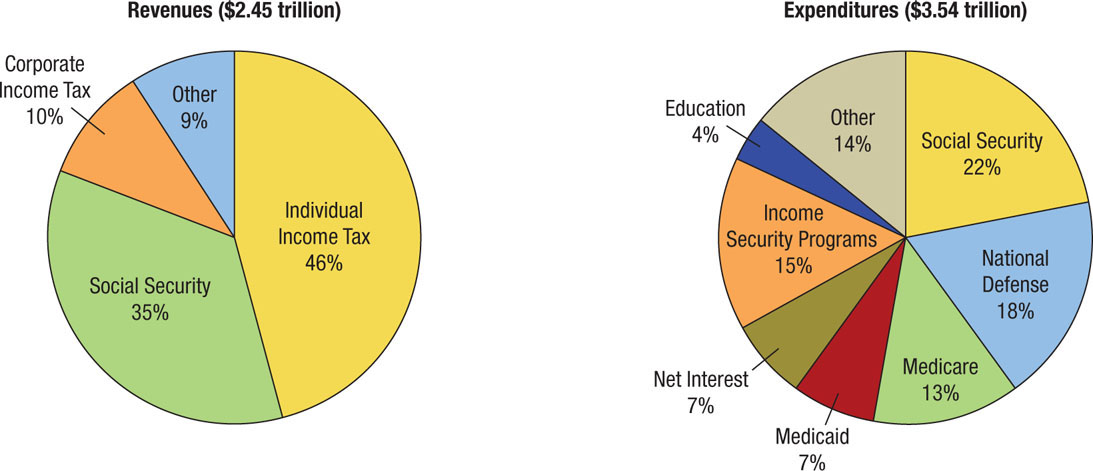

The government collected $2.45 trillion in 2012 primarily from individual income taxes and Social Security (payroll) taxes. It spent $3.54 trillion, over half on national defense, Social Security, and Medicare.

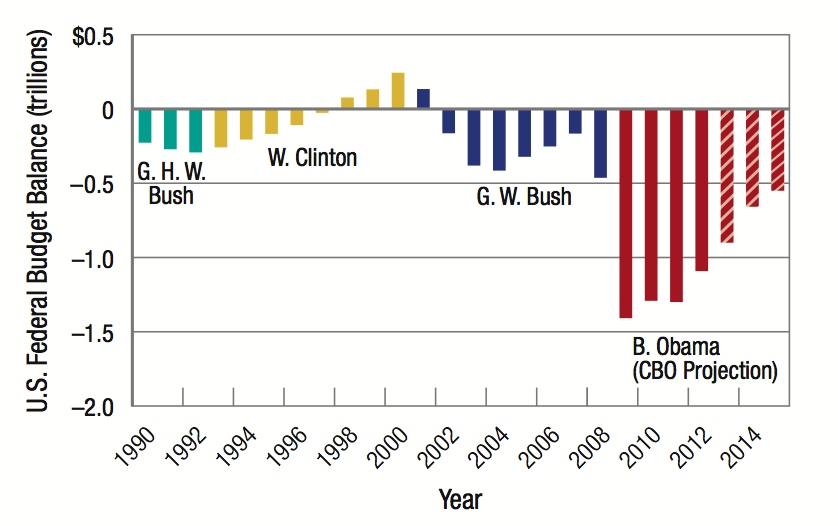

U.S. federal government expenditures exceeded revenues in every year since 1990 except from 1998 to 2001. The gap between spending and revenues expanded in 2008 as a result of the recession.

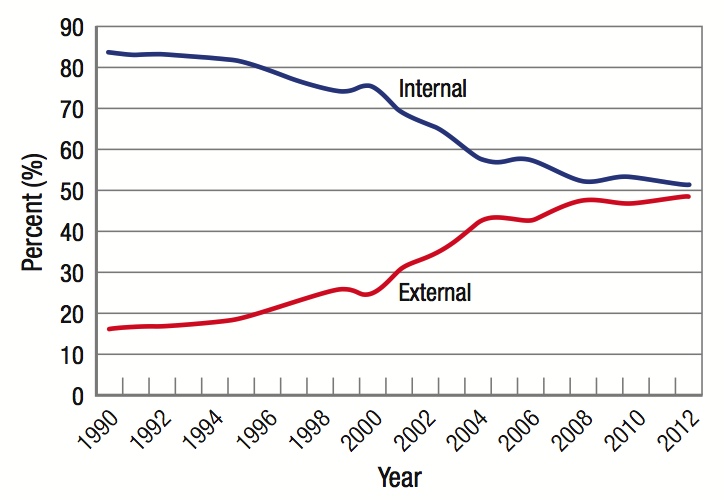

External (foreign held) debt has risen since 1990. Today, nearly 50% of total public debt is held externally.

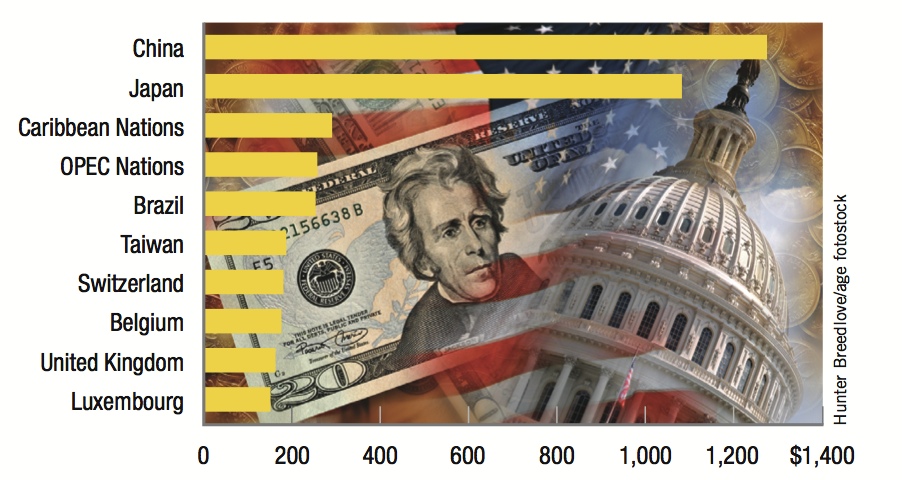

Top Ten Creditors of U.S. Treasury Debt as of July 2013 (in billions)